Abstract

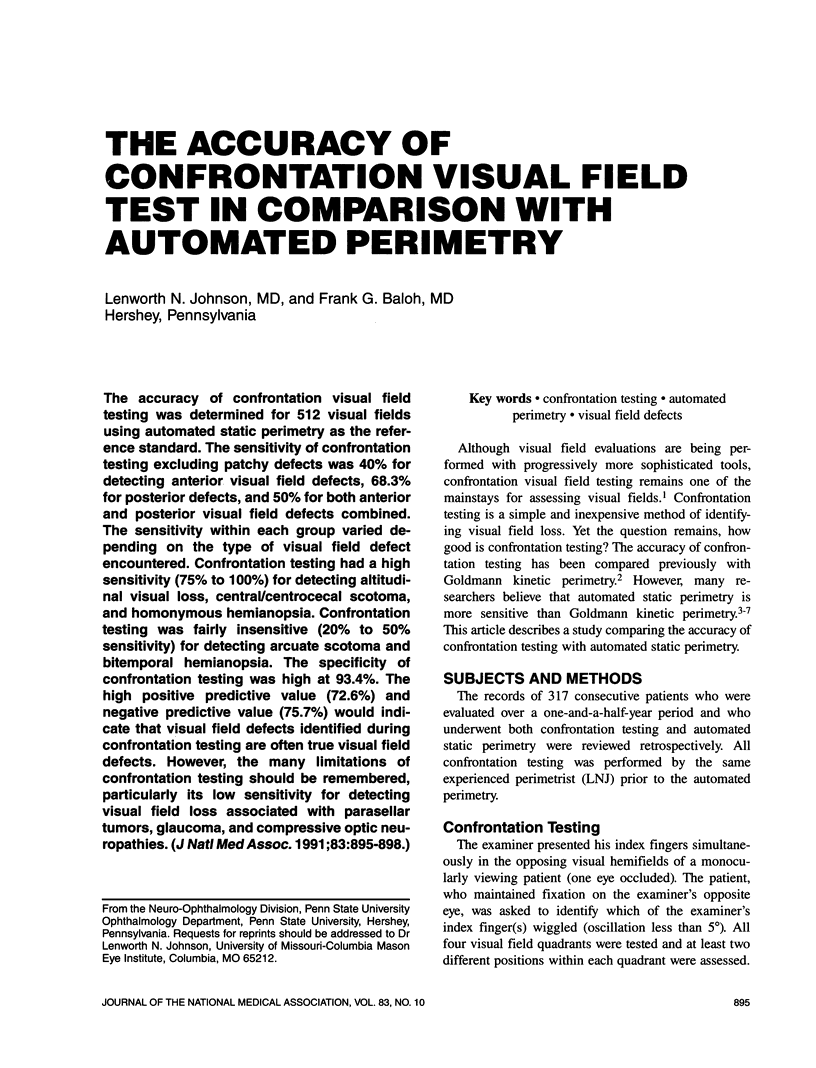

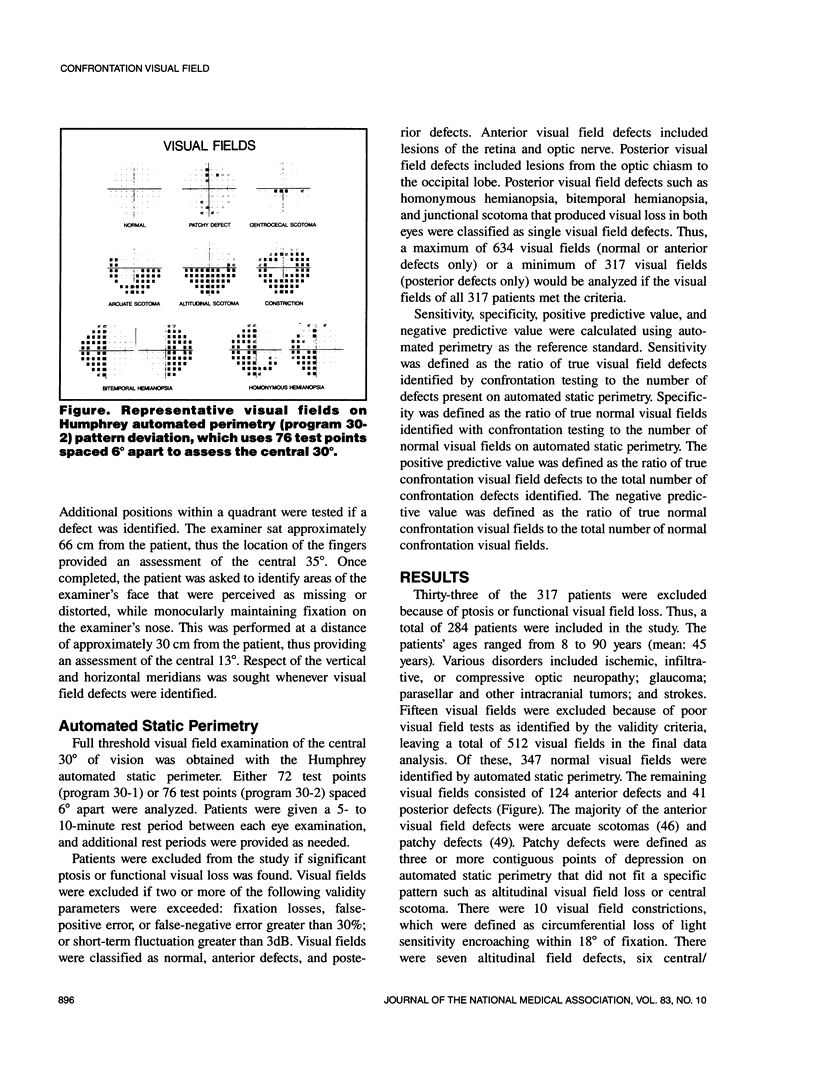

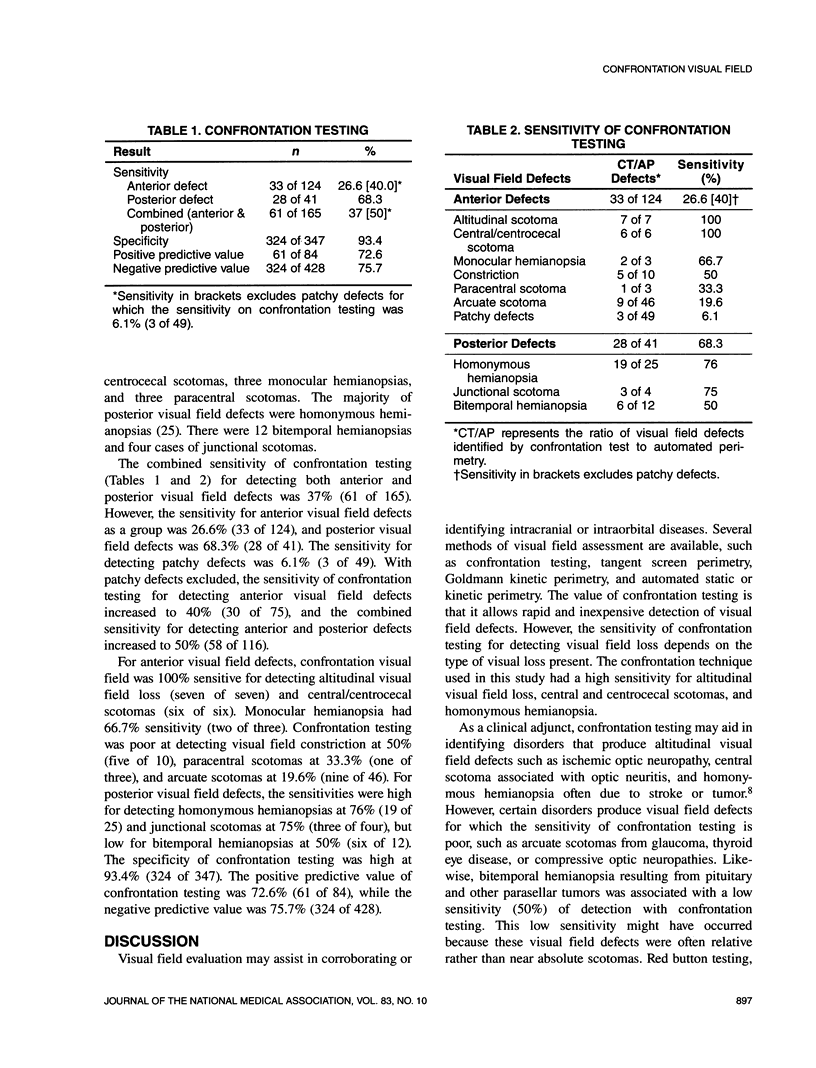

The accuracy of confrontation visual field testing was determined for 512 visual fields using automated static perimetry as the reference standard. The sensitivity of confrontation testing excluding patchy defects was 40% for detecting anterior visual field defects, 68.3% for posterior defects, and 50% for both anterior and posterior visual field defects combined. The sensitivity within each group varied depending on the type of visual field defect encountered. Confrontation testing had a high sensitivity (75% to 100%) for detecting altitudinal visual loss, central/centrocecal scotoma, and homonymous hemianopsia. Confrontation testing was fairly insensitive (20% to 50% sensitivity) for detecting arcuate scotoma and bitemporal hemianopsia. The specificity of confrontation testing was high at 93.4%. The high positive predictive value (72.6%) and negative predictive value (75.7%) would indicate that visual field defects identified during confrontation testing are often true visual field defects. However, the many limitations of confrontation testing should be remembered, particularly its low sensitivity for detecting visual field loss associated with parasellar tumors, glaucoma, and compressive optic neuropathies.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Beck R. W., Bergstrom T. J., Lichter P. R. A clinical comparison of visual field testing with a new automated perimeter, the Humphrey Field Analyzer, and the Goldmann perimeter. Ophthalmology. 1985 Jan;92(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman L. Epidemiology of eye disease in the elderly. Eye (Lond) 1987;1(Pt 2):330–341. doi: 10.1038/eye.1987.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe G. J., Alvarado J. A., Juster R. P. Age-related changes of the normal visual field. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986 Jul;104(7):1021–1025. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050190079043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. A., Keltner J. L. Optimal rates of movement for kinetic perimetry. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987 Jan;105(1):73–75. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060010079035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrary J. A., 3rd, Feigon J. Computerized perimetry in neuro-ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 1979 Jul;86(7):1287–1301. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(79)35398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer M. Sight-saving month calls attention to eye care. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988 May;106(5):593–593. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060130647014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trobe J. D., Acosta P. C., Krischer J. P., Trick G. L. Confrontation visual field techniques in the detection of anterior visual pathway lesions. Ann Neurol. 1981 Jul;10(1):28–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winward K. E., Smith J. L. Ocular disease in Caribbean patients with serologic evidence of Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1989 Jun;9(2):65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]