Abstract

Recent changes to the organisation and delivery of primary care in the UK have the potential to reduce continuity of care markedly, but it is not clear how this will have an impact on patient trust. This study aims to test the associations between specific aspects of continuity in the GP–patient relationship, and patient trust, informed by the theoretical framework of behavioural game theory. A cross-sectional survey of patients in three Leicestershire general practices was conducted. Regression analysis showed that ratings of the GP's interpersonal care, past experience of cooperation, and expectation of continuing care from the GP were all independent predictors of patient trust. These findings highlight the value of longitudinal aspects of the GP–patient relationship.

Keywords: continuity of patient care, cross-sectional studies, primary health care, trust

INTRODUCTION

Trust is generally acknowledged to be a core component of the GP–patient relationship. It is important in its own right and it mediates other positive outcomes, including adherence to treatment.1 Recent changes to the organisation and delivery of primary care in the UK have the potential to reduce continuity of care markedly,2 as patients are increasingly likely to be consulting unfamiliar health professionals. It is not clear how this will have an impact on patient trust.

The limited research on the association between continuity and trust suggests that trust is promoted by the quality of the GP–patient relationship, and in particular the interpersonal aspects of the GP's care of the patient.3–6 There is a need to determine whether and how the longitudinal aspects of the GP–patient relationship affect patient trust.

This study uses a theoretical framework (behavioural game theory) as a basis for predictions about the specific aspects of continuity that promote trust.7 Game theory indicates that trust is promoted when people interact with each other repeatedly, and particularly when individuals are aware of their partners' cooperativeness on past occasions (either from personal experience or reputation), have a reputation for cooperativeness themselves, and anticipate ongoing interactions in the future – described as the ‘shadow of the future’.8 Hence, game theory points to information about past cooperativeness, and an expectation of future interactions, as important determinants of trust.

This study aimed to test whether these dimensions of continuity, identified from game theory, are associated with patients' trust in GPs.

METHOD

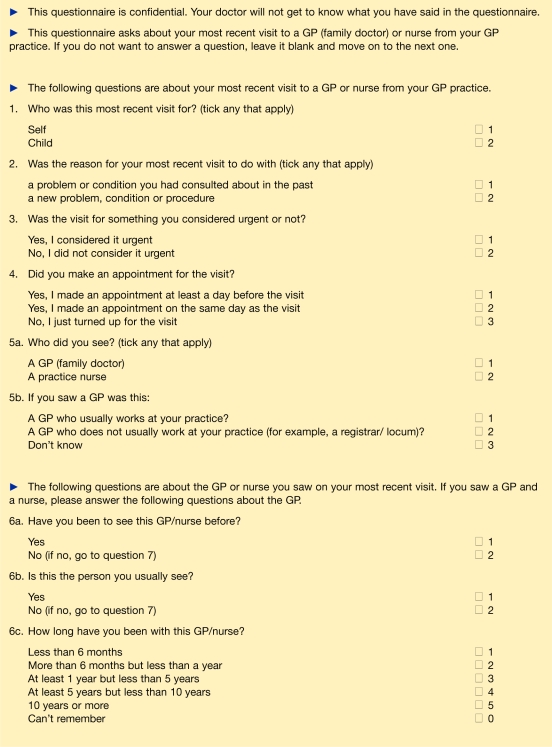

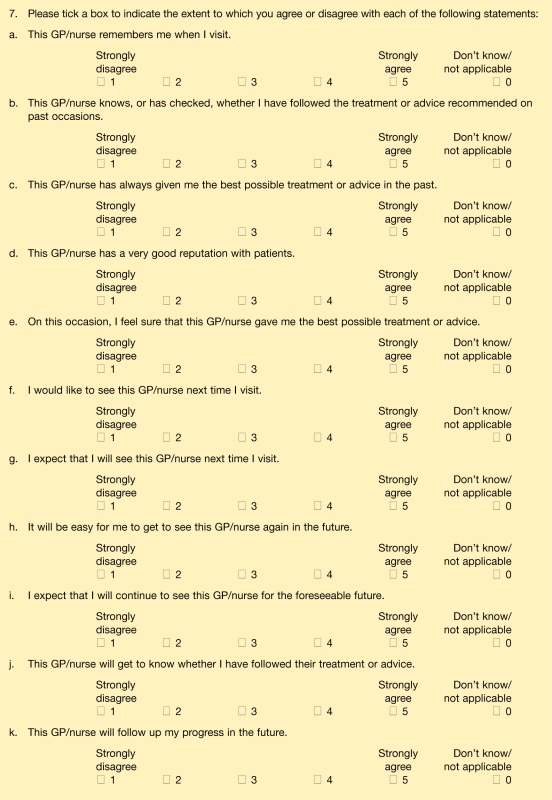

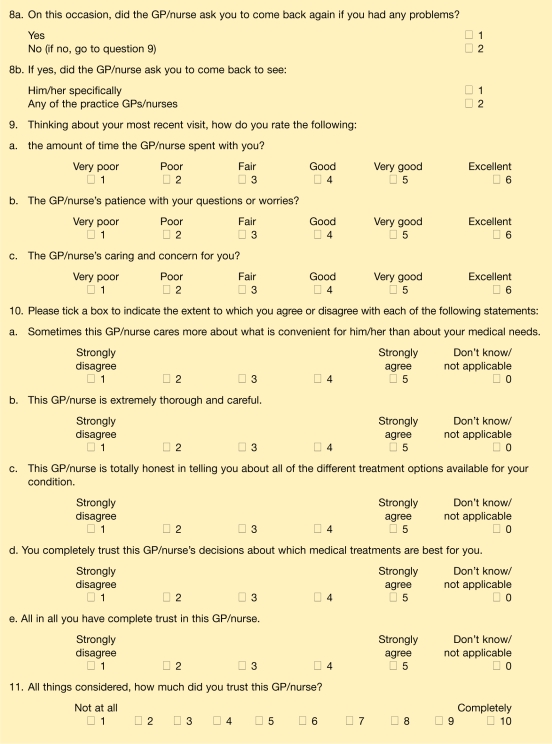

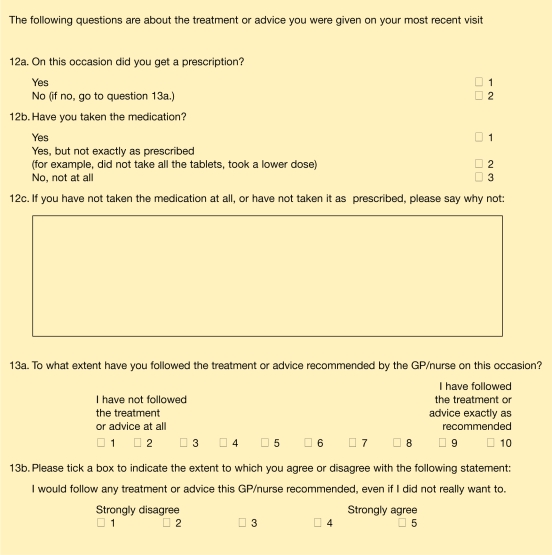

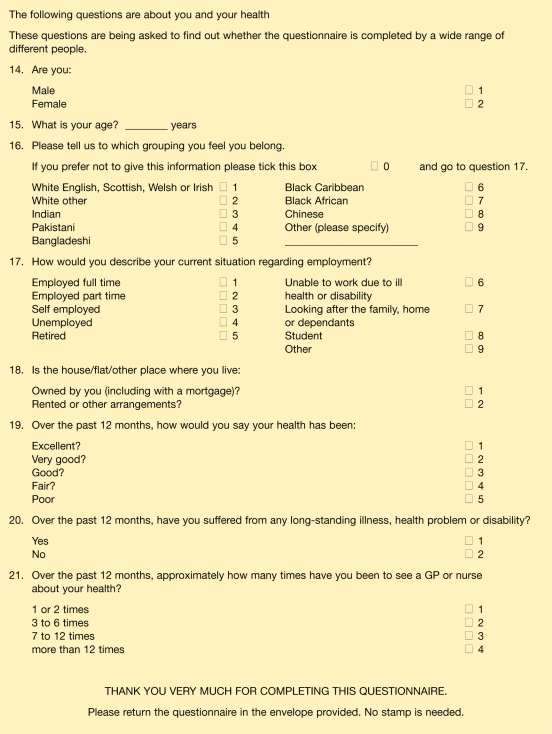

A questionnaire was developed and piloted prior to use. The questionnaire included a series of questions on aspects of continuity, devised specially for this study. These questions were based on specific hypotheses derived from the framework of behavioural game theory. The questions on continuity consisted of statements accompanied by a five-point Likert scale labelled from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Evidence of cooperativeness in the past was assessed by the questions ‘This GP has always given me the best possible treatment or advice in the past’ and ‘This GP knows, or has checked, whether I have followed the treatment or advice recommended on past occasions’. Anticipation of the future was assessed by the question ‘This GP will follow up my progress in the future’. The questionnaire measured interpersonal care through the use of a single subscale from the General Practice Assessment Survey (GPAS) questionnaire (the ‘interpersonal care’ subscale),9 consisting of three questions asking patients to rate the amount of time the GP spent with them, the GP's patience, and caring and concern (Appendix 1, question 9). Trust was measured using the short form Interpersonal Trust in Physician Scale,10 which produces a trust score out of 100 (Appendix 1, question 10). The questionnaire was pretested through a postal pilot study involving 50 patients in a single GP practice, to assess response patterns and identify questions with very skewed responses or a large number of missing responses. Participants were asked for feedback on the content of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was revised as a result of this piloting.

The questionnaire was posted to a sample of 593 patients from three Leicestershire general practices (Appendix 2), in March and April 2005. Sample size was calculated from published guidelines for multiple regression analysis.11 Patients who had consulted at the practice over the past 2 weeks were selected at random from practice records, after excluding patients aged <18 years and >75 years. Data were analysed in SPSS using t tests, Pearson's and point-biserial correlation, and multiple linear regression analysis (method: Enter).

RESULTS

The questionnaire was returned by 279 patients (47%). Thirty-six patients did not see a GP at their most recent visit, but saw a practice nurse. These questionnaires were excluded, leaving 243 questionnaires for analysis. Characteristics of responders are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of responders (n = 243).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean age, years (range, SD) | 50.0 (18–75, 15.84) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 84 (34.6) |

| Female | 157 (64.6) |

| Ethnicity, | |

| White British | 202 (83.1) |

| White other | 12 (4.9) |

| Indian | 14 (5.8) |

| Pakistani | 3 (1.2) |

| Black African/Caribbean | 4 (1.6) |

| Other | 1 (0.4) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 117 (48.2) |

| Retired | 60 (24.7) |

| Unable to work due to illness | 24 (9.9) |

| Looking after family | 17 (7.0) |

| Other | 19 (7.8) |

| Health status | |

| Excellent | 17 (7.0) |

| Very good | 49 (20.2) |

| Good | 81 (33.3) |

| Fair | 64 (26.3) |

| Poor | 28 (11.5) |

| Longstanding illness | |

| Yes | 135 (55.6) |

| No | 105 (43.2) |

SD = standard deviation.

The results of multiple regression analysis are shown in Table 2. Although patients who saw their usual GP had significantly higher trust scores than those who did not (83.5 compared to 72.6, t = 3.53, P = 0.001), this did not emerge as an independent predictor of trust. Interpersonal care was the strongest predictor of trust. Good care from the GP in the past, belief that the GP knew or had checked whether the patient had followed the treatment or advice recommended on past occasions, and the patient's expectation that the GP would provide follow-up care in the future also emerged as significant independent predictors of trust.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression analysis on trust score.

| Standardised | Correlation with trust scorea | Standardised regression coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Usual GP? (1 = no, 2 = yes) | 0.23b | −0.01 (−0.10 to 0.08) |

| Interpersonal care | 0.77b | 0.47b (0.34 to 0.60) |

| This GP knows or has checked whether I have followed the treatment or advice recommended on past occasions | 0.62b | 0.15b (0.01 to 0.29) |

| This GP has always given me the best possible treatment or advice in the past | 0.69b | 0.20b (0.07 to 0.33) |

| This GP will follow up my progress in the future | 0.69b | 0.18b (0.05 to 0.31) |

| Age | 0.20b | −0.03 (−0.12 to 0.06) |

| Sex (1 = male, 2 = female) | −0.14b | −0.02 (−0.11 to 0.07) |

| Ethnicity (1 = white, 2 = other) | −0.12 | 0.03 (−0.06 to 0.12) |

Adjusted R2 = 0.70.

Significant at P<0.001.

significant at P<0.05.

Correlation calculated is Pearson's r, except for dichotomous variables (for example, sex), where the point biserial correlation (rpb) was used.

How this fits in

Patient trust is an important feature of primary care that may be threatened by reduced continuity of care resulting from new modes of delivery such as polyclinics. This study shows that positive ratings of a GP's interpersonal care, experiences of mutual cooperation between patient and GP in the past, and patients' expectations of continuing care from the same GP in the future are all associated with higher patient trust. This suggests that continuity of care and expectation of care from the same GP in the future are important in promoting patient trust.

The impact of patients' expectations of future care from the GP is underlined by the finding that patients who reported that the GP had asked them to come back and see him/her specifically in the future had higher trust scores than patients who had not been asked this by the GP (mean trust scores: 86.06 and 67.09 respectively, t = 5.65, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

Interpersonal care, information about past cooperation, and expectation of continuing care from their GP in the future were all independent predictors of trust. Overall, these findings are in line with game theory predictions that positive experiences in past interactions (or evidence of past cooperative behaviour), and the ‘shadow of the future’, promote trust.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The following study limitations are noted. First, the survey involved a relatively small number of patients from three Leicestershire general practices, and the response rate was relatively low. Due to the method of sampling used, the sample may be over-inclusive of patients who had consulted full-time as opposed to part-time GPs. The percentage of female compared to male responders was relatively high, although this is common in surveys of primary care patients. Hence, the sample may not be fully representative of the population of the practices involved, and the generalisability of the findings may be correspondingly limited. Second, although significant findings emerged on the relationship between continuity and trust, it should be emphasised that this is a cross-sectional study, and it is not valid to infer causality from the findings.

Comparison with existing literature

Patients' rating of interpersonal care in the consultation was the strongest predictor of trust, as identified by previous research.3–6,12,13 Patients also had higher trust when they had experienced good-quality care in the past and when they felt the GP knew them to be a cooperative patient; previous research has reported that positive shared experiences in the past have an impact on trust.3,14 Patients also had higher trust when they believed the GP would follow them up in the future. Although trust has been conceptualised as ‘forward looking and reflect[ing] a commitment to an ongoing relationship’,15 this study is the first to provide empirical support for the association between anticipation of future care and trust.

Seeing the ‘usual GP’ did not emerge as an independent predictor in the regression analysis. The findings of this study indicate that trust is nuanced and is based on a range of evidence suggesting trust is warranted, including interpersonal aspects of the consultation, evidence of good care in the past, and evidence of commitment to future care. These findings suggest that seeing the ‘usual GP’ in itself is not sufficient to promote trust, but is likely to have value in that it provides an opportunity for past interactions to be judged as cooperative,3 and for future interactions to be anticipated with more certainty.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

The study findings merit exploration and development. The key finding is that longitudinal elements of continuity have an impact on patient trust, over and above the influence of the GP's interpersonal skills. Further empirical work should be undertaken to confirm this finding, and to test and explore ‘anticipation of the future’ as a dimension of continuity. Future research aiming to define and measure continuity should take note of the conceptualisation of continuity provided by game theory.

The study has important implications for practice. Although trust can be engendered outside of ongoing GP–patient relationships, the aspects of continuity of information and experience that were found to promote patient trust are more likely to feature when care is given by the same GP over time. This suggests that the current trend towards increased access and choice in primary care, at the expense of ongoing interpersonal continuity, may undermine patient trust. Ways of minimising this in primary care could include encouraging GPs to ask patients to come back to see them again personally, and putting practice systems in place to ensure that this is made easy for the patient (for example, flexible appointment booking systems). However, it should also be recognised that the shift towards providing primary care through alternative services, such as walk-in centres and polyclinics, may mean that opportunities for GPs and patients to build committed partnerships over time are lost.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the three general practices and the patients who took part in the study.

Appendix 1. Full questionnaire.

Appendix 2. Characteristics of participating practices.

| Locality | Number of partners | List size | Deprivationa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice 1 | Inner city | Medium (5–7) | 12000+ | High |

| Practice 2 | Urban | Medium (5–7) | 6000–12000 | High |

| Practice 3 | Market town | Large (>7) | 12000+ | Moderate |

Based on Townsend Score: Townsend P, Phillimore P, Bealtie A. Health and deprivation: inequality and the north. London: Croom Helm, 1988.

Funding body

This study was partly funded through a grant from the University of Leicester Faculty of Medicine and Biological Sciences Research Committee

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was gained from the Leicestershire Research Ethics Committee

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Thom DH, et al. Patient trust in the physician: relationship to patient requests. Fam Pract. 2002;19(5):476–483. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.5.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman GK. Continuity of care: an essential element of modern general practice? Fam Pract. 2003;20:623–627. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caterinicchio RP. Testing plausible path models of interpersonal trust in patient–physician treatment relationships. Soc Sci Med. 1979;13A(1):81–99. doi: 10.1016/0160-7979(79)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarrant C. Factors associated with patients' trust in their general practitioner: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(495):798–800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thom DH, et al. Further validation and reliability testing of the trust in physician scale. Med Care. 1999;37(5):510–517. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safran DG, et al. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36(5):728–739. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarrant C. Models of the medical consultation: opportunities and limitations of a game theory perspective. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(6):461–466. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.008417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Axelrod R. The evolution of cooperation. New York: Basic Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroter S, et al. The General Practice Assessment Survey (GPAS): tests of data quality and measurement properties. Fam Pract. 2000;17(5):372–379. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.5.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dugan E. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green SB. How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis? Multivar Behav Res. 1991;26:499–510. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2603_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thom DH. Patient-physician trust: an explanatory study. J Fam Pract. 1997;44(2):169–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mechanic D. Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(5):657–668. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mainous AG. Patient-physician shared experiences and value patients place on continuity of care. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):452–454. doi: 10.1370/afm.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calnan M. Trust in health care: an agenda for future research. London: The Nuffield Trust; 2004. p. 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]