Abstract

Metal affinity capture tandem mass spectrometry (MAC-MSMS) is evaluated in a comparative study of a lysine-derived nitrilotriacetic acid (Nα, Nα-bis-(carboxymethyl)lysine, LysNTA) and an aspartic-acid-related iminodiacetic acid (N-(4-aminobutyl)aspartic acid, AspIDA) as selective phosphopeptide detection reagents. Both LysNTA and AspIDA spontaneously form ternary complexes with GaIII and phosphorylated amino acids and phosphopeptides upon mixing in solution. Collision-induced dissociation of positive complex ions produced by electrospray produces common fragments (LysNTA + H)+ or (AspIDA + H)+ at m/z 263 and 205, respectively. MSMS precursor scans using these fragments as reporter ions allow one to selectively detect multiple charge states of phosphopeptides in mixtures. It follows from this comparative study that LysNTA is superior to AspIDA in detecting phosphopeptides, possibly because of the higher coordination number and greater stability constant for GaIII – phosphopeptide complexation of the former reagent. In a continuing development of MAC-MSMS for proteomics applications, we demonstrate its utility in a post-column reaction format. Using a simple post-column-reaction ‘T’ and syringe pump to deliver our chelating reagents, α-casein tryptic phosphopeptides can be selectively analyzed from a solution containing a twofold molar excess of bovine serum albumin. The MAC-MSMS method is shown to be superior to the commonly used neutral loss scan for the common loss of phosphoric acid.

Keywords: metal affinity capture, phosphopeptides, proteomics, collision-induced dissociation, tandem mass spectrometry, gallium metal complexes

INTRODUCTION

The importance of protein phosphorylation in biology and medicine1,2 is reflected by the considerable efforts to develop methods for the selective detection of phosphopeptides by mass spectrometry. Many methods in current practice use metal-assisted separation of peptide mixtures, which relies on the selective affinity of phosphopeptides to trivalent metal ions (FeIII, GaIII) that are immobilized on a solid support (IMAC).3-6 Alternative column materials are titanium and zirconium dioxide, which have been shown to surpass IMAC in some applications and represent an interesting alternative to IMAC,7-10 with new materials having been developed recently.11 Dissociations of gas-phase ions have also been reported that showed selectivity to the presence of a phosphate group in the peptide.12-16 These mainly include elimination of phosphoric acid from phosphoserine (pSer) and phosphothreonine (pThr) residues, which can be monitored as neutral loss of 98 Da from singly charged precursor ions, or 98/2, 98/3, etc. fractions for multiply charged ions.13 Although widely used, this approach has known drawbacks in that (1) phosphopeptides may not be protonated efficiently by electrospray owing to the presence of the acidic phosphate group(s), (2) elimination of phosphoric acid from phosphotyrosine residues (pTyr) is inefficient, and (3) only one charge state of the precursor ion is revealed in any neutral loss scan while the other charge states must be monitored in separate scans.

In a previous report we showed that phosphopeptides can be captured in solution by chelation to gallium (III) in a ternary complex with Nα, Nα-bis-(carboxymethyl)lysine (LysNTA) as a co-ligand, ionized by electrospray in positive ion mode and selectively detected in a technique involving tandem mass spectrometry, which we called metal-ion affinity capture (MAC-MSMS).17 The interesting features of MAC-MSMS were (1) facile formation of positive [GaIII(LysNTA) − phosphopeptide]n+ ions by electrospray, (2) selectivity of the chelated gallium ion for phosphopeptide capture, and (3) the use of a universal, singly charged marker ion, (LysNTA + H)+ at m/z 263, which is generated by collision-induced dissociation (CID), which allowed us to simultaneously monitor all phosphopeptide charge states in a single precursor ion scan. Another advantage of the MAC-MSMS method compared to the neutral loss scan is that it allows one to detect phosphotyrosine-containing peptides, because the ion dissociation does not involve the phosphate group.

We present here two new approaches to further evaluate the MAC-MSMS method. First, we attempted to alleviate nonspecific binding of acidic residues to the gallium metal ion by using an alternative chelating reagent. Since the viability of GaIII has already been evaluated by previous studies,6,17 we focused on N-(4-aminobutyl)aspartic acid (AspIDA), which can be viewed as an iminodiacetic acid (IDA) derivative and an alternative to LysNTA. IDA is used in place of nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) as the functional reagent for many commercial IMAC products including Propac IMAC (Dionex), Phosphopeptide Isolation Kit (Pierce Biotechnology), and the Phosphoprotein Purification Kit (Quiagen). In one study, IDA was found to be superior to NTA in selectivity and sensitivity when immobilized on agarose for IMAC.18 In particular, we wish to compare the relative utilities of LysNTA versus AspIDA for the formation and detection of ternary phosphopeptide complexes in solution. Depending on the pH, AspIDA can be a 2- or 3-coordinate metal binding reagent that contains a free primary amino group in the side chain to facilitate protonation in positive mode electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS).

In addition to studying AspIDA, we continued the development of the MAC-MSMS method with LysNTA as the chelating reagent in the selective detection of phosphopeptides from tryptic digests of complex mixtures. Our previous work focused on detecting phosphopeptides from tryptic digests from a single protein without prior separation.17 Recognizing the need to combine this method with a separation technique to analyze more complex samples, we demonstrate the use of a reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) separation followed by a post-column online reaction19 for MAC-MSMS phosphopeptide detection.

EXPERIMENTAL

Methods

Electrospray ionization mass spectra were acquired on either a Waters TQD tandem quadrupole, or a Bruker Esquire ion trap mass spectrometer, each operated in positive ion mode. Measurements on the Bruker Esquire ion trap instrument were performed with a 30 V skimmer potential and a 70 V capillary exit offset. Optimum ESI was achieved at a capillary voltage of 4000 V and a nitrogen drying gas flow rate of 5–6 ml/min. Optimal trap drive settings were sample dependent, falling within the range of 55–65 instrument units. ESI-MS measurements on the Waters TQD tandem quadrupole instrument were performed with the capillary at 3.5 kV, a cone voltage of 25 V, and an extraction lens voltage of 2 V. For RPLC-MSMS experiments, the ESI source temperature was set to 80°C. Nitrogen drying gas was supplied at a flow rate of 700 l/h and heated to 350°C. The collision cell entrance and exit potentials were 30 and 5 V, respectively, with a collision energy of charge multiples of 30 eV and an Ar collision gas flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. MSn spectra on the ion trap were obtained for confirmation and initial characterization of phosphopeptide complexes. Tandem MS data were acquired on the Waters TQD instrument in the MS scan, neutral loss scan, or precursor ion scan modes. RPLC separations were performed on a Zorbax 300 Extend-C18 column with a 2.1 mm diameter, 100 mm length, and 3.5 μm particle size. Triply protonated precursors were selected for neutral scans (loss of 32 u for H3PO4) because they represented the most commonly occurring phosphopeptide ions for the protein samples under study.

AspIDA was synthesized from dimethyl maleate (Aldrich) and N-Boc-1,4-diaminobutane (Fluka). Briefly, dimethyl maleate was slowly added to the t-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc)-protected 1,4-diaminobutane in dry t-butanol with stirring at room temperature. The reaction was allowed to proceed overnight at room temperature and then refluxed for 1 h before being cooled. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the clear oily residue was purified over silica gel using 10 : 1 CHCl3: MeOH as eluent. Boc deprotection was achieved by stirring the product in 50% anhydrous TFA in dichloromethane. Methyl ester hydrolysis involved refluxing the resulting primary amine in 2 m HCl for 2 h. The solvent and by-products were removed by evaporation to yield AspIDA.

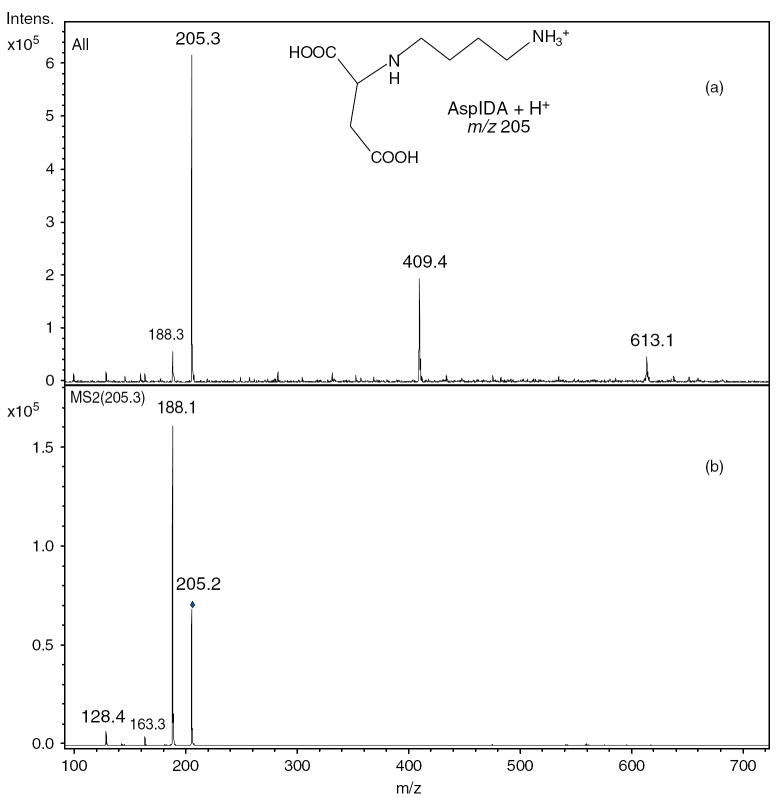

The AspIDA product was characterized by ESI-MS (MH+ at m/z 205). CID of (AspIDA + H)+ precursor ions at m/z 205 leads to consecutive eliminations of NH3 and C2H4O2 (presumably CH2 = C(OH)2), giving rise to fragments at m/z 188 and 128, respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

(a) ESI-MS and (b) MSMS of N-(4-aminobutyl)aspartic acid (AspIDA, MH+ m/z 205) acquired on an ion trap instrument.

AspIDA–metal-ion complexes were formed with GaCl3 (Aldrich). The formation constant for (IDA)GaIII complexes of 1 : 1 ligand–metal-ion stoichiometry are on the order of 1013 (see Ref. 20). Thus, a large excess of GaIII is not required to drive the complex formation to completion. A 2 : 1 ratio of metal to AspIDA was sufficient to facilitate complete complex formation, as determined by the absence of the free (AspIDA + H)+ ion (m/z 205) in the ESI-MS spectrum of metal–AspIDA solutions. Excess of AspIDA led to increased formation of (AspIDA)nGan−1 ion clusters.

The peptides used to characterize the ternary (AspIDA) GaIII(peptide) complexes included NQLLpTPLR, QLLpTPLR, MpSGIFR, MSGIFR, and pYWQAFR, which were purchased from Genscript Corporation, Piscataway, NJ. The same peptides were used previously to evaluate LysNTA.17 Peptides from the tryptic digestion of αS1-casein were also used to characterize the formation of ternary complexes with AspIDA and GaIII. Sequence-grade trypsin, α-casein, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Aldrich. All other reagents were from Sigma, St Louis, MO. Tryptic digestions were performed at a 1:50 enzyme to substrate ratio (w/w) in 20 mm NH4HCO3 and incubated overnight at 37°C Prior to digestion, proteins were denatured in 6 m urea for 15 min at 40°C. The denatured proteins were then diluted 5 times with water prior to reduction and alkylation with dithiothreitol and iodoacetamide, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Phosphopeptide complexes with AspIDA and GaIII were examined for their relative utility with the MAC-MSMS selective phosphopeptide detection strategy. To begin, we determined that the optimum solvent conditions for complex formation were no different than those using LysNTA. Specifically, complex formation and subsequent ESI were carried out in an aqueous buffer of 20% methanol and 0.1% acetic acid. While optimal [(AspIDA − 2H)Ga]+ complex formation occurs at an AspIDA : GaIII ratio of 1 : 2, optimal formation of ternary [(AspIDA − H)Ga(pSer − H)]+ occurs at an AspIDA : GaIII ratio of 1 : 1. This is likely due to the increased competition between free gallium and chelated gallium for the phosphorylated residue under conditions of excess metal ion. This leads to increased phosphopeptide binding to free gallium rather than the desired AspIDA chelated form.

Formation constants (β) were determined as described previously.17 Briefly, the ternary pSer complex signal at m/z 456 (Im/z 456, Eqn (1)) was measured by ESI-MS as a function of pSer concentration [pSer]0 at two different concentrations of AspIDA ([AspIDA]0) and GaCl3 ([GaIII]0), and the response slopes (m, Eqn (2)) were fitted in Eqn (3) to eliminate the unknown response factor (αm/z 456) of the complex.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Equation (1) is valid when the reagent concentrations, [AspIDA]0 and [GaIII]0, are much greater than the concentration of ternary complex at equilibrium. Thus, formation constants were determined using AspIDA and GaCl3 reagent concentrations of both 500 and 1000 μm while the pSer concentration was varied from 1 to 10 μm. Furthermore, Eqn (2) is valid under the assumption that the instrumental sensitivity factor (α) is not dependent on the reagent concentrations. That is, the AspIDA and GaCl3 concentrations will be expected to effect complex formation but not ESI or MS detection.21 The formation constants of ternary pSer complexes with AspIDA and GaIII (β) were measured in the acidic buffer described above and found to be around 3.2 × 106/mol2. This is 2 orders of magnitude smaller than the β for the same complexes of pSer with LysNTA and Ga3+. The lower β-values for ternary complex formation are probably due to the lower coordination number (CN) of AspIDA compared to LysNTA. As shown below, this results in an increased availability of the AspIDA-bound GaIII to non-phosphopeptides.

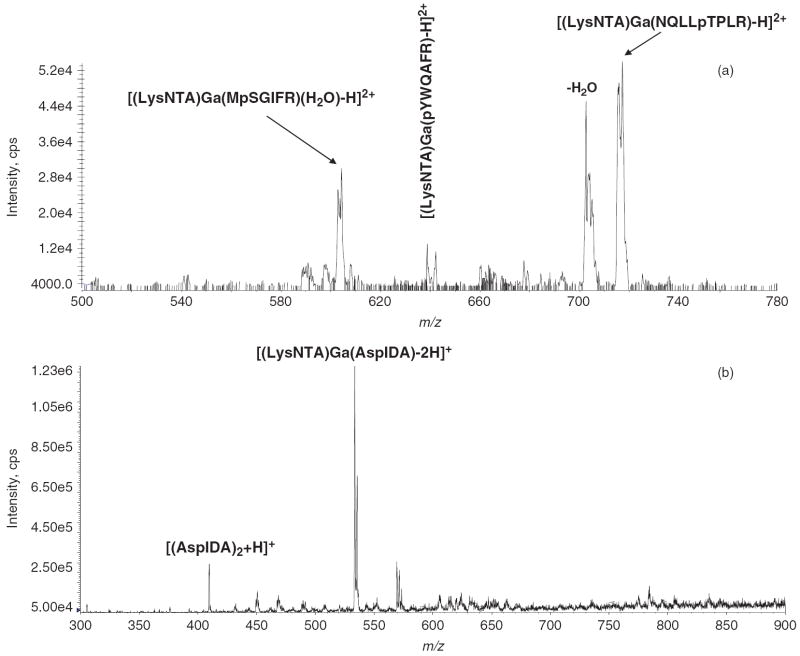

In spite of the smaller phosphopeptide complex formation constant relative to LysNTA, AspIDA was still evaluated in a MAC-MSMS method to observe possible advantages in selectivity or sensitivity. Figure 2(a) shows an ESI-MS spectrum of a mixture of 500 μm AspIDA, 500 μm GaCl3, and 10 μm of a synthetic phosphopeptide, MpSGIFR. The ESI-MS spectrum suggests that approximately 50% of the phosphopeptide is present as a [(MpSGIFR)GaIII (AspIDA) − H]2+ complex ion at m/z 530 (for 69Ga). Note that one of the ligands is deprotonated in the complex. The proportion of bound to unbound MpSGIFR is roughly similar to that for complex formation with (LysNTA)GaIII.17 CID, Fig. 2(b), of the m/z 530 ternary complex gave complementary fragments consisting of (AspIDA + H)+ at m/z 205, and a galliated phosphopeptide ion at m/z 856. In fact, this was a common fragmentation for all phosphopeptide complexes of AspIDA and Ga3+. Thus the m/z 205 fragment could be used as a marker ion in a selective precursor-ion scanning method, such as MAC-MSMS.

Figure 2.

(a) ESI-MS spectrum of a mixture of 500 μm AspIDA, 500 μm GaCl3, and 10 μm of a synthetic phosphopeptide, MpSGIFR. (b) Collision-induced dissociation (CID) mass spectrum of the ternary phosphopeptide complex ion at m/z 530.8.

The precursor-ion scanning method for the common m/z 205 product ion from phosphopeptide complexes of AspIDA and Ga3+ was evaluated for selectivity and sensitivity using a mixture of four synthetic peptides, MpSGIFR, pYWQAFR, NQLLpTPLR, and MSGIFR. Figure 3 shows a precursor-ion scan from a mixture of these four peptides, each at a concentration of 10 μm in a solution containing 500 μm AspIDA and 500 μm GaCl3. The phosphopeptide complex signals are obviously much more abundant than the non-phosphopeptide signal, presumably as a result of selective binding to the AspIDA-bound gallium ion. It is worth noting here that when LysNTA was used, the [(MSGIFR)GaIII(LysNTA) − H]2+ complex signal was virtually undetected. In contrast, the non-phosphopeptide AspIDA complex peak appears in the spectrum when AspIDA is used with the MAC-MSMS method. Thus, the [(AspIDA)Ga − 2H]+ species is apparently more susceptible to nonspecific binding to peptide carboxylates. Furthermore, the large [(AspIDA)2Ga − 2H]+ complex signal at m/z 475 indicates that AspIDA itself is able to compete with the phosphopeptide for coordination to Ga3+.

Figure 3.

Precursor-ion scan for the common (AspIDA + H)+ daughter ion (m/z 205) from phosphopeptide complexes. The mixture consisted of 500 μm AspIDA, 500 μm GaCl3 and 10 μm of four peptides: MSGIFR, MpSGIFR, NQLLpTPLR, pYWQAFR.

The lower selectivity of AspIDA-bound gallium for phosphopeptides may be due to the lower CN of the AspIDA ligand, CN = 3, relative to that of the LysNTA ligand, CN = 4. Since Ga3+ is typically hexacoordinated in aqueous solution, a second LysNTA is inhibited from binding to the two remaining coordination sites on [(LysNTA)Ga − 2H]+. Thus, the phosphate moiety, CN = 2, is more capable of competing with LysNTA than AspIDA for the remaining Ga3+ coordination sites in these respective mixtures. In more complex samples, such as the tryptic digest from α-casein, the use of AspIDA with GaIII leads to the detection of only a few ternary phosphopeptide complexes in the precursor-ion scan spectrum above the background of non-phosphopeptide clusters with AspIDA and Ga3+ (Fig. 4). Thus, nonspecific binding seems to occur more readily when using AspIDA-bound gallium as opposed to the LysNTA-bound species.

Figure 4.

Precursor-ion scan for the common (AspIDA + H)+ fragment ion (m/z 205) from complexes of AspIDA and GaIII. The mixture contained 500 μm AspIDA, 500 μm GaCl3, and 10 μm α-casein tryptic digest.

The utility of AspIDA relative to LysNTA with the MAC-MSMS phosphopeptide detection method was further illustrated in a competitive binding experiment wherein phosphopeptide was added to a 1 : 1 mixture of the two chelating reagents under gallium limiting conditions. As is apparent from separate precursor-ion scanning experiments performed on this mixture, LysNTA clearly outcompetes AspIDA for phosphopeptide binding (Fig. 5). Under these conditions, the precursor-ion scan for the (LysNTA + H)+ (m/z 263) product ion leads to the detection of considerable amounts of phosphopeptide complexes. In contrast, precursor-ion scanning for (AspIDA + H)+ (m/z 205) in this mixture does not yield a phosphopeptide complex signal and, interestingly, yields a strong signal corresponding to a mixed complex, [(AspIDA)GaIII(LysNTA) − 2H]+. This suggests that AspIDA also outcompetes phosphopeptide for the remaining coordination sites on LysNTA-bound gallium. On the basis of these data, LysNTA appears to be more desirable than AspIDA for phosphopeptide analysis by MAC-MSMS.

Figure 5.

Selective detection of phosphopeptides in a 1 : 1 mixture of AspIDA and LysNTA under gallium limiting conditions. (a) Precursor-ion scanning for LysNTA complexes (m/z 263) and (b) AspIDA (m/z 205). The mixture contained 10 μm of each MSGIFR, MpSGIFR, NQLLpTPLR, and pYWQAFR with 500 μm LysNTA, 500 μm AspIDA, and 250 μm GaCl3 in aqueous 20% methanol/0.1% acetic acid.

MAC-MSMS with post-colum reaction

The MAC-MSMS phosphopeptide detection technique with LysNTA and GaIII was evaluated for use in a post-column reaction format with RPLC. Sample preparation prior to analysis typically involved a tryptic digestion of the protein mixture to form peptides that are amenable to detection with ESI-MS. These digests usually require large amounts of salt and additives that serve to denature the proteins, reduce their disulfide bonds, and buffer to the functioning pH of the protease. The high salt concentrations inhibit both peptide detection by ESI-MS and complex formation with LysNTA and GaIII for MAC-MSMS. Thus, a desalting step is necessary prior to analysis. One method for desalting uses a pipette tip packed with reversed phase material (e.g. C18 ZipTip, Waters)17; however, this has been shown to sacrifice significant amounts of highly polar phosphopeptides. Thus, an online desalting protocol using an RPLC separation with a post-column reaction was desirable to facilitate MAC-MSMS phosphopeptide detection and to eliminate losses associated with the incomplete binding of phosphopeptides to the C18 resin of a ZipTip.

The post-column reaction approach was evaluated as a selective phosphopeptide detection technique in tryptic mixtures of α-casein with BSA. A post-column-reaction ‘T’ fitting (Upchurch Scientific) was inserted immediately following the column, and the reagents were supplied in aqueous 20% methanol/0.1% acetic acid at a flow rate of 300 μl/h delivered by a Harvard Apparatus syringe pump. The MAC-MSMS reagent concentrations were optimized at 200 μm LysNTA and 200 μm GaCl3 for this particular application. At higher reagent concentrations, specifically 500 μm or 1 mm, the (LysNTA)nGaIIIn−1 species became increasingly prominent adding to baseline noise without significantly increasing the phosphopeptide complex signal. Peptide separations were achieved at a flow rate of 200 μl/min with an LC mobile phase gradient starting at 100% A (H2O with 10% methanol, 0.1% acetic acid) and ramping to 60% B (methanol, 0.1% acetic acid) over 60 min.

Sample injections for method validation consisted of a tryptic digest of 10 pmol BSA and 5 pmol α-casein prepared using the digestion protocol described earlier.17 The resulting ion chromatogram based on the MAC-MSMS precursor-ion scan with post-column reaction is shown in Fig. 6(a) and is compared to detection by both a neutral loss (−32.7 Da) scanning technique (Fig. 6(b)) as well as a standard ESI-MS analysis using total ion current without a MAC-MSMS post-column reaction (Fig. 6(c)). Figure 6(a) shows that the singly phosphorylated α-casein peptides are selectively detected from the non-phosphopeptide background with a much greater sensitivity than with the neutral loss scanning technique and with better selectivity than the simple ESI-MS experiment. The singly phosphorylated α-casein peptide signals become the major peaks in the MAC-MSMS chromatogram (Fig. 6(a)). The MS/MS spectrum of the precursor ion giving the most abundant signal in Fig. 6(a) (m/z 761.8, inset) shows it to be the α-casein tryptic phosphopeptide, YKVPQLEIVPNpSAEER, residues 119–134, which has formed a complex with a single Ga and LysNTA.17 The precursor-ion scanning method is both highly selective and sensitive for the detection of phosphopeptide complexes. We note that multiply phosphorylated peptides may be more difficult to detect as positive ions because of their low basicity and therefore lower ionization efficiency in electrospray.22 The same problem is encountered with phosphopeptide ions produced by protonation.23,24 Our continuing studies on optimization of ionization conditions will address this issue with tryptic digests from in vitro protein phosphorylation.

Figure 6.

Tryptic digest of 10 pmol α-casein and 20 pmol bovine serum albumin separated by RPLC as described in text. (a) Post-column reaction with 200 μm LysNTA and 200 μm GaCl3 with selective detection by precursor-ion scanning for precursors generating the common daughter ion at m/z 263. Inset shows the precursor ion at m/z 761.8, which corresponds to a triply charged complex of YKVPQLEIVPNpSAEER, residues 119–134, with a single Ga and LysNTA. (b) Neutral loss scanning for the common loss of 32.7 Da from triply charged phosphopeptides, no post-column reaction. (c) MS scan for all species present in sample, no post column reaction. Asterisks denote singly phosphorylated peptide or phosphopeptide complex ions.

The complication with neutral loss scanning for these larger (>10−15 residues) phosphopeptides derives from the increased likelihood of other fragmentation pathways competing with the loss of phosphoric acid as the number of peptide bonds increases. This disadvantage may be overcome by digestion with multiple proteases to create smaller peptides whose phosphoric acid elimination remains a dominant loss in low-energy CID. MAC-MSMS provides an attractive alternative to detect larger phosphopeptides because the fragment ion at m/z 263 from the ternary phosphopeptide complexes remains a dominant loss in CID even for larger (>15 residues) tryptic peptides. This may be explained by the increased tendency of the phosphopeptide residues coordinated to Ga3+ to transfer protons to the chelated LysNTA. Presumably, this facilitates the formation of the (LysNTA + H)+ product ion while inhibiting competing dissociations along the peptide backbone. A drawback of such a sensitive marker ion is a loss of backbone fragmentation information useful for phosphopeptide sequencing. This disadvantage may be mitigated by the isotope encoding afforded by the gallium ion. Since 69Ga and 71Ga are naturally present in a 60 : 40 ratio, the charge states may be more readily defined allowing for more reliable determinations of peptide m/z values in the absence of fragmentation information. Distinction of 69Ga and 71Ga isotopologues is contingent on the resolving power of the instrument and may become limiting for higher charge states. Nonetheless, the MAC-MSMS method is still useful with targeted strategies to monitor dynamic phosphorylation state changes of known phosphorylation sites. Biological studies to this end are in progress in this laboratory.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated the successful implementation of the MAC-MSMS method for the selective detection of phosphopeptides from a complex mixture. An alternative chelating reagent, AspIDA, was found to be inferior to LysNTA for the MAC-MSMS method. The relative performance of these two chelating species may be due to their formation constants for ternary phosphopeptide complexes with GaIII. The lower CN of AspIDA probably allows for less specific binding than LysNTA to the Ga metal center. A post-column reaction scheme with LysNTA and Ga was demonstrated to show that complex mixtures with high salt concentrations are amenable to online RPLC analysis with MAC-MSMS. The high salt concentrations generated from typical tryptic digests mandate a desalting step prior to analysis by ESI-MS. The ternary phosphopeptide complexes with LysNTA and Ga were thus formed in a post-column format following separation by RPLC. Phosphopeptides from a 2 : 1 mole/mole mixture of BSA and α-casein were selectively detected with sensitivity far superior to the common neutral loss scanning approach. The novelty of the MAC-MSMS method compared to scanning for the neutral loss of phosphoric acid includes the ability to provide a common phosphopeptide marker ion even for larger peptides (>10−15 residues).

Acknowledgments

Support of this work by the NIH (Grant DK67869) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Published online 11 February 2008 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com)

References

- 1.Fischer EH, Krebs EG. Phosphorylase activity of skeletal muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1955;216:113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen P. The origins of protein phosphorylation. Nature Cell Biology. 2002;4:E127. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porath J, Carlsson J, Olsson I, Belfrage G. Metal chelate affinity chromatography, a new approach to protein fractionation. Nature. 1975;258:598. doi: 10.1038/258598a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson L, Porath J. Isolation of phosphoproteins by immobilized metal (Fe3+ affinity chromatography. Analytical Biochemistry. 1986;154:250. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hochuli E, Dobeli H, Schacher A. New metal chelate adsorbent selective for proteins and peptides containing neighboring histidine residues. Journal of Chromatography. 1987;411:177. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)93969-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Posewitz MC, Tempst P. Immobilized gallium (III) affinity chromatography of phosphopeptides. Analytical Chemistry. 1999;71:2883. doi: 10.1021/ac981409y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sano A, Nakamura H. Titania as a chemo-affinity support for the column-switching HPLC analysis of phosphopeptides: application to the characterization of phosphorylation sites in proteins by combination with protease digestion and electrospray mass spectrometry. Analytical Sciences. 2004;20:861. doi: 10.2116/analsci.20.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinkse JWH, Uitto PM, Hilhorst MJ, Ooms B, Heck AJR. Selective isolation at the femtomole level of phosphopeptides from proteolytic digests using 2D-nanoLC-ESI-MS/MS and titanium oxide precolumns. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76:3935. doi: 10.1021/ac0498617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen MR, Thingholm TE, Jensen ON, Roepstorff P, Jorgensen TJD. Highly selective enrichment of phosphorylated peptides from peptide mixtures using titanium dioxide micro-columns. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2005;4:873. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kweon HK, Hakansson K. Selective zirconium dioxide-based enrichment of phosphorylated peptides for mass spectrometric analysis. Analytical Chemistry. 2006;78:1743. doi: 10.1021/ac0522355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blacken GR, Volný M, Vaisar T, Sadílek M, Tureček F. In situ enrichment of phosphopeptides on maldi plates functionalized by reactive landing of zirconium(IV)-n-propoxide ions. Analytical Chemistry. 2007;79:5449. doi: 10.1021/ac070790w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carr SA, Huddleston MJ, Annan RS. Selective detection and sequencing of phosphopeptides at the femtomole level by mass spectrometry. Analytical Biochemistry. 1996;239:180. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Schwartz JC, Hunt DF, Coon JC. A neutral loss activation method for improved phosphopeptide sequence analysis by quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76:3590. doi: 10.1021/ac0497104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang EJ, Archambault V, McLachlin DT, Krutchinsky AN, Chait BT. Analysis of protein phosphorylation by hypothesis-driven multiple-stage mass spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76:4472. doi: 10.1021/ac049637h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flora FW, Muddiman DC. Gas-phase ion unimolecular dissociation for rapid phosphopeptide mapping by IRMPD in a penning ion trap: an energetically favored process. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:6546. doi: 10.1021/ja0261170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowe MC, Brodbelt JS. Differentiation of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated peptides by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-infrared multiphoton dissociation in a quadrupole ion trap. Analytical Chemistry. 2005;77:5726. doi: 10.1021/ac0509410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blacken GR, Gelb MH, Turecek F. Metal affinity capture tandem mass spectrometry for the selective detection of phosphopeptides. Analytical Chemistry. 2006;78:6065. doi: 10.1021/ac060509y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nuhse TS, Stensballe A, Jensen ON, Peck SC. Large-scale analysis of in vivo phosphorylated membrane proteins by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2003;2:1234. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T300006-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohler M, Leary JA. LC/MS/MS of carbohydrates with postcolumn addition of metal chlorides using triaxial electrospray probe. Analytical Chemistry. 1995;67:3501. doi: 10.1021/ac00115a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martell AE, Smith RM. Critical Stability Constants, Vol. 1: Amino Acids. Plenum Press; New York: 1974. pp. 116–142. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Marco VB, Bombi GG. Electrospray mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) in the study of metal-ligand solution equilibria. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 2006;25:347. doi: 10.1002/mas.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Zhang C, Campbell JL, Zhang H, Yeung KK, Han VKM, Lajoie GA. Formation of phosphopeptide-metal ion complexes in liquid chromatography/electrospray mass spectrometry and their influence on phosphopeptide detection. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2005;19:2747. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballard JNM, Lajoie GA, Yeung KK. Selective sampling of multiply phosphorylated peptides by capillary electrophoresis for electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analysis. Journal of Chromatography A. 2007;1156:101. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Ambrosio C, Salzano AM, Arena S, Rensone G, Scaloni A. Analytical methodologies for the detection and structural characterization of phosphorylated proteins. Journal of Chromatography B. 2007;849:163. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]