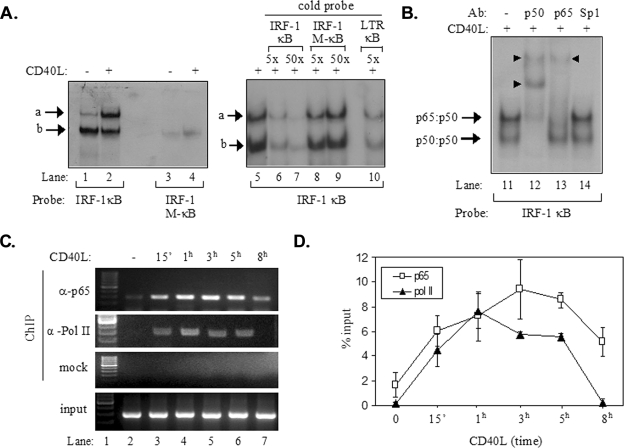

FIG. 4.

Recruitment of p65 NF-κB to the IRF-1 promoter following CD40 ligation. (A) Results from EMSAs showing the in vitro binding of nuclear proteins to a radiolabeled probe containing the NF-κB binding site of IRF-1, forming complexes a and b (lanes 1 to 2 and 5 to 10). Binding was not observed when a radiolabeled probe containing a mutated NF-κB binding site (IRF-1 M-κB) was used (lanes 3 and 4). Excess cold IRF-1 κB or HIV LTR κB but not IRF-1 M-κB oligonucleotide effectively competed with complexes a and b for binding to the radiolabeled IRF-1 κB probe (lanes 5 to 10). +, present; −, absent. (B) Results from EMSAs showing the effects of antibodies (Ab) to p65 and p50 NF-κB or Sp1 on the electrophoretic mobilities of complexes a and b (lanes 11 to 14). The supershift in lanes 12 and 13 (marked with arrowheads) suggests that complex a contained p65-p50 heterodimers. (C and D) Results from a representative ChIP assay (C) and collective data from four experiments (D) showing the kinetics of the in vivo recruitment of p65 and of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) to the IRF-1 promoter. ChIP assays were performed as described in detail in Materials and Methods. One-tenth of the volume of the chromatin obtained was used for PCR as input, and the remaining volume was immunoprecipitated with anti-p65 (α-p65) or anti-RNA polymerase II (α-Pol II) antibodies or without antibody (mock). Precipitated DNA encompassing the IRF-1 promoter was then assayed by PCR. The quantification of the results was performed by measuring the intensities of the bands using the Tinascan version 2 software, and the levels of recruitment are expressed as percentages of recruited protein relative to the input (D). 15′, 15 min.