Summary

The development of fibrosis involves a multitude of events and molecules. Until now the majority of these molecules were found to be proteins or peptides. But recent data show significant involvement of the phospholipid lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) in the development of pulmonary, liver and renal fibrosis. The latest data on the role of LPA and the G-protein-coupled LPA1 receptor in the development of renal fibrosis will be discussed. LPA1 receptor-activation was found to be associated with increased vascular leakage and increased fibroblast recruitment in pulmonary fibrosis. Furthermore, in renal fibrosis LPA1 receptor-activation stimulates macrophage recruitment and connective tissue growth factor expression. The observations make this receptor an interesting alternative and new therapeutic target in fibrotic diseases.

Renal fibrosis

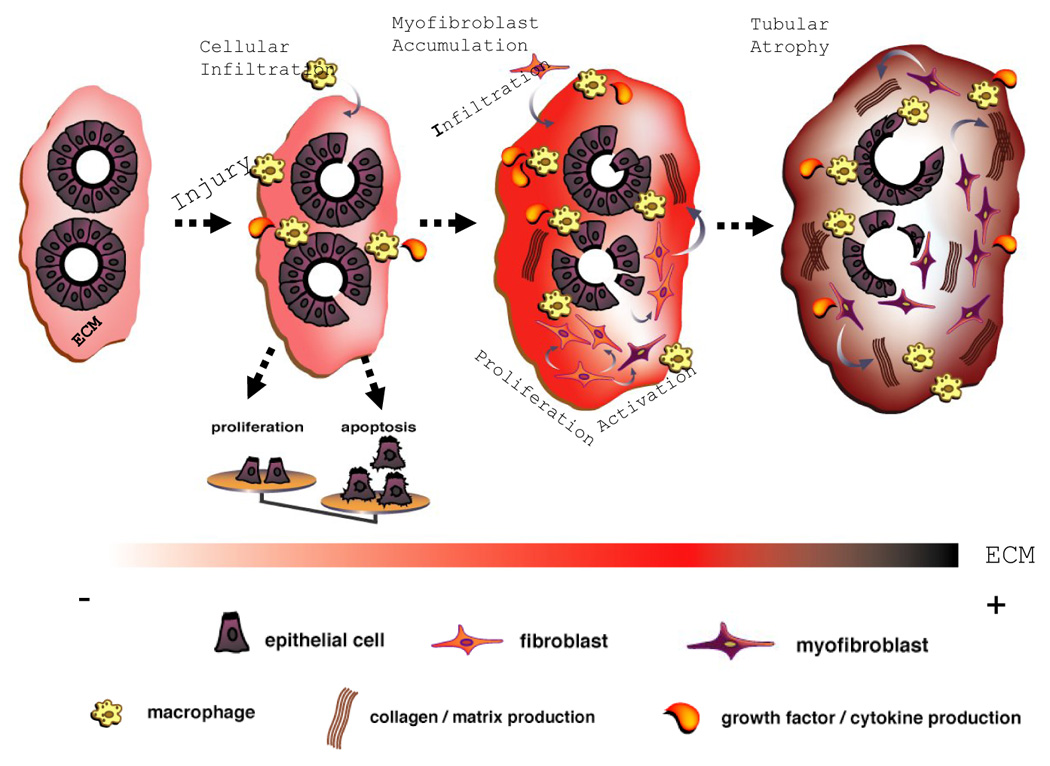

Renal fibrosis is the principal process involved in the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). As the incidence of ESRD continues to increase throughout the world, research to better understand the development of renal fibrosis has intensified [1, 2]. The development of renal fibrosis involves the progressive appearance of glomerulosclerosis, tubulointerstitial fibrosis (TIF) and changes in renal vasculature (loss of glomerular and peritubular capillaries). On a molecular level, fibrosis can be defined as excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM), such as collagens and fibronectins. The presence of TIF, compared to glomerular sclerosis, has been strongly correlated to evolution to ESRD [1, 3]. The first step in the development of TIF is inflammation associated with infiltration of macrophages, lymphocytes, and an increase in cytokine and chemokine seceretion (Figure 1). This inflammatory state induces a disequilibrium between apoptosis and proliferation of tubular cells, as well as accumulation of myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts arise from epithelial mesenchymal transition, from proliferation/activation of the few resident fibroblasts or from infiltrated cells [1, 4]. These myofibroblasts are the main cell type responsible for the secretion of the ECM. As these events occur, the quantity of fibrotic tissue increases, causing a steady decline of renal function until eventually the kidney is no longer able to function and organ failure occurs. In the past a number of mediators of TIF have been identified including chemokines, cytokines and growth factors [5]. Among these, transforming growth factor (TGF)β is thought to be the most fibrogenic, directly or indirectly, through the action of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) [6].

Figure 1. Overview of the different stages in the development of renal fibrosis.

The development of fibrosis in CKD is comparable between the different renal compartments [1]. For clarity the development of only renal TIF is shown. The first step in the development of TIF is renal inflammation. This is leading to infiltration of macrophages, lymphocytes, and to increased cytokine and chemokine secretion. This inflammatory state induces a disequilibrium between apoptosis and proliferation of tubular cells, as well as accumulation of myofibroblasts. These myofibroblasts are the main cell type responsible for the secretion of the ECM. As CKD progresses, ECM deposition becomes massive and uncontrolled apoptosis of tubular cells leads to tubular atrophy. This figure was adapted from [4], with permission.

As most renal disease converts sooner or later to renal fibrosis, treatment aiming to slowdown, halt, or even better, reverse renal fibrosis will have an enormous impact in renal disease. The multitude of events and factors [5] involved in the development of renal fibrosis is reflected by the increasing number of experimental reports showing the potential anti-fibrotic effect of a number of strategies and compounds [2, 3]. However, the only currently clinically available drugs which have shown to slow down the progression towards ESRD are the inhibitors of the renin angiotensin system (RAS, [1]). Unfortunately, even when treated with RAS inhibitors CKD continues to progress. Alternative molecules or therapies are thus necessary [2, 3].

Phospholipids and Fibrosis

For the majority of organs and tissues the development of fibrosis involves a multitude of events and factors [7], similar to what described above for the kidney. Until now, the majority of these molecules were found to be proteins or peptides (profibrotic cytokines, chemokines, metalloproteinases etc… [7]). But more recent data show significant involvement of phospholipids in wound healing [8] and in the development of fibrosis. These phospholipids include platelet activating factor (PAF), phosphatidyl choline and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA). Involvement of these three phospholipids in the development of fibrosis in various organs will be presented below, with a particular emphasis on LPA.

In vitro studies show PAF as an important actor in the development of renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis. PAF induces the production of the ECM-components collagen type I et IV and fibronectin by rat fibroblasts and tubular cells [9]. PAF also induces the production of the profibrotic cytokine TGFβ [10]. In vivo, genetic ablation or pharmacological blockade of the PAF receptor induces a significant decrease of folic acid-induced renal fibrosis in rodent models [11]. Furthermore, PAF is also involved in pulmonary fibrosis as administration of a PAF receptor antagonist attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis [12].

Other phospholipids are associated with the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Different studies describe an increase of phospholipid concentrations in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and in particular phosphatidylcholine (PC) in rabbits and rodents injected with bleomycin [13, 14]. The production of PC under these conditions might be beneficial as it was shown that dilinoleoylphosphatidylcholine in vitro and in vivo, induces a significant reduction in the expression of genes coding for ECM molecules and inflammatory mediators during bile duct ligation-induced liver fibrosis [15].

LPA and fibrosis

LPA is a growth factor-like phospholipid known to regulate several cellular processes including cell motility, cell proliferation, cell survival, and cellular differentiation. LPA acts on specific G-protein coupled receptors (LPA1 to LPA5) [16]. Pharmacological tools to study the involvement of these different LPA receptors have been limited. Currently, the most frequently used pharmacological agent is Ki16425 that has been shown to block LPA1- and LPA3-receptor subtypes both in vitro [17] and in vivo [18]. Mice invalidated for the LPA receptor subtype 1, 2 and 3 are also available [19–21]. Among the different bioactive phospholipids, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) has been associated with the etiology of a growing number of disorders [22]. Furthermore, a number of studies suggest a role for LPA in the development of fibrosis (see the discussion below).

A number of muscular dystrophies are characterized by a progressive weakness and wasting of musculature, and by extensive fibrosis. It has been shown that LPA-treatment of cultured myoblasts induced significant expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). CTGF subsequently induces collagen, fibronectin and integrin expression and induces dedifferentiation of these myoblasts [23]. This example is introducing the unambiguous link between LPA and CTGF; it has been shown that treatment of a variety of cell types with LPA induces reproducible and high level induction of CTGF [24–32], although not necessarily in cells directly involved in the fibrotic process. CTGF is an important profibrotic cytokine, signaling down-stream and in parallel with TGFβ [33]. In this context CTGF expression by gingival epithelial cells, which are involved in the development of gingival fibromatosis, was found to be exacerbated by LPA treatment [34].

LPA might also be associated with the progression of liver fibrosis. In vitro, LPA induces stellate cell and hepatocyte proliferation [35]. These activated cells are the main cell type responsible for the accumulation of ECM in the liver [36]. Furthermore, LPA plasma levels raise during CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rodents, or in hepatitis C virus-induced liver fibrosis in human [37, 38].

In addition it was recently shown, in an elegant study of Tager et al., that LPA is an important protagonist in the evolution of pulmonary fibrosis [39]. They first showed that LPA is detected in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) and that its concentration is significantly increased in BAL of bleomycin-challenged mice. In the next step it was shown that genetic ablation (LPA1 receptor knockout mice) or pharmacological knockdown (Ki16425) of the LPA1 receptor reduced bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis and increased animal survival. Complementary studies further demonstrated that profibrotic effects of LPA1 receptor stimulation might be explained by LPA1 receptor-mediated vascular leakage and increased fibroblast recruitment, both profibrotic events. Finally, in human pulmonary fibrosis it was shown that LPA and the LPA1 receptor also play an important role. The LPA1 receptor was the LPA receptor most highly expressed on fibroblast obtained from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Furthermore, BAL obtained from IPF patients induced chemotaxis of human foetal lung fibroblasts that was blocked by the LPA1 receptor antagonist Ki16425 [39]. Taken together these studies show that the LPA1 receptor is a potential target in treatment of IPF. Unfortunately the role of CTGF in this pulmonary profibrotic action of LPA was not studied [39].

Finally, we have recently identified a role for LPA and the LPA1 receptor in the development of renal fibrosis which will be discussed in detail below after a more general state of the art of the knowledge of LPA and its role in renal pathophysiology.

LPA and renal pathophysioloy

In vivo

Only little information is available on the in vivo involvement of LPA in renal disease. LPA was shown to attenuate lesions induced by ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) in mice by inhibition of caspase-dependent apoptosis in tubular cells and reduced complement activation and neutrophil recruitment [40]. However, this protective role of LPA in I/R injury has been contested since the use of the LPA3 receptor antagonist (VPC12249) induced a significant decrease in, and the use of a LPA analogue (OMPT) enhanced, the lesions induced by I/R [41]. Further studies are necessary to better define the role of LPA and its receptors in renal I/R injury. Other studies on patients with chronic renal failure have shown the presence of increased LPA concentrations in plasma [42, 43]. These studies showed that in 18 dialyzed patients with renal failure, plasma LPA levels were 3-fold higher in dialyzed patients than in controls (respectively 1,41 ± 0,16 nmol/mL and 0,54 ± 0,08 nmol/mL). These data suggest an abnormal LPA metabolism with renal failure, but the cause and consequences of elevated LPA levels under these conditions remains to be clarified [42]. As the renal expression of LPA receptors is relatively high (especially LPA1/2 and LPA3 receptors, [31, 41]), this organ might be targeted by these high plasma LPA concentrations.

In vitro

Separately from these in vivo experiments, the expression of LPA receptors and the effects of LPA treatment on a variety of renal cell types were studied. It seems that, in vitro, LPA can induce biological effects on the majority of the kidney cell types: mesangial cells, renal tubular cells or renal fibroblasts.

Mesangial cells (For review [44])

Mesangial cells are an important cell type in the glomerulus, which is the filtration unit of the kidney. Mesangial cell activation (exemplified by mesangial profibrotic chemokine and cytokine secretion) and proliferation was identified in a number of renal pathologies [1]. LPA induces mesangial cell proliferation via mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation, contractility mediated by intra-cellular calcium mobilization, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) accumulation, and prostaglandin E2 synthesis [45–47]. LPA can also be a mesangial cell survival factor, effects that are mediated by the Pi3k/Akt pathway [48]. Finally, LPA induces CTGF production by human mesangial cells [49]. With this large variety of biological responses on mesangial cells, it is most likely that LPA is an important actor in glomerular pathologies.

Proximal tubular cells

LPA induces tubular cell proliferation mediated by Pi3k/MAP kinase pathway activation and can inhibit serum starvation-induced apoptosis via the Pi3k/Akt pathway in primary culture of human tubular cells [45, 50]. LPA is also able to induce intra-cellular calcium mobilization in opossum kidney proximal tubule cells [51]. This increase might be the onset of NHE3 channel translocation and activation in apical membrane of tubular cells, consequently inducing Na++ absorption [52, 53]. Finally, it was shown that primary culture human proximal tubular cells express the LPA1 receptor [54].

Renal fibroblasts

LPA can induce CTGF expression and secretion, which is mediated by small GTPase Rho activation [29].

LPA and renal fibrosis

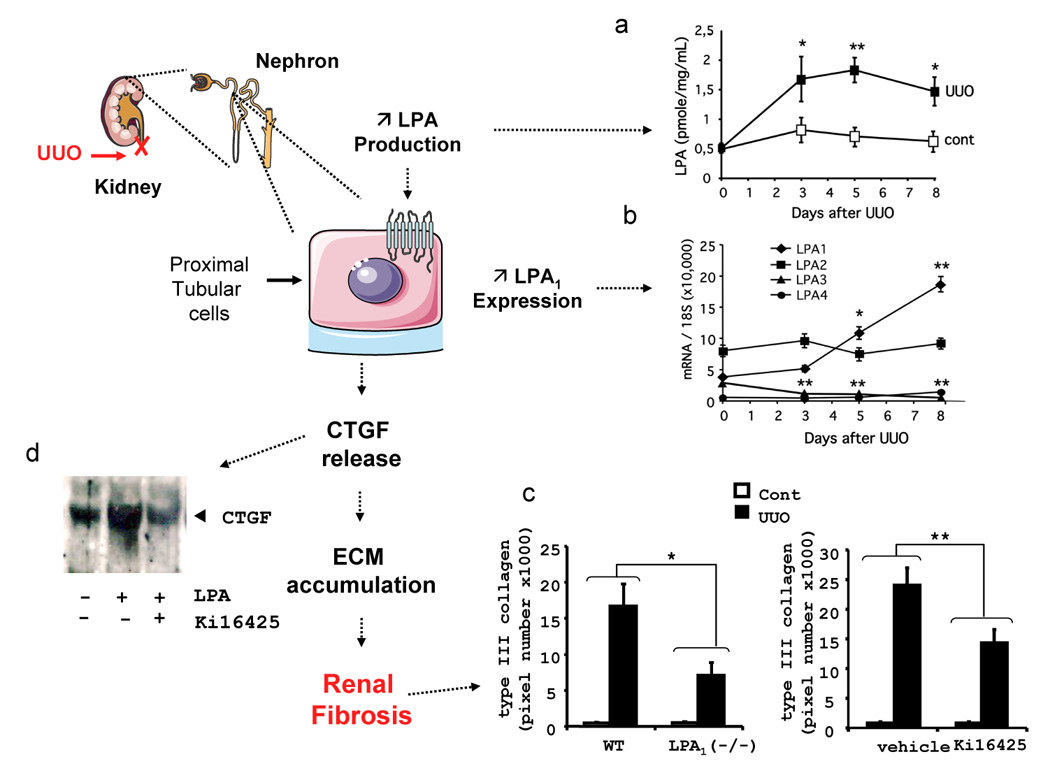

Both in vitro and in vivo, LPA can mediate a number of processes involved in fibrosis and renal pathology. However, clear evidence for the involvement of LPA in the development of renal fibrosis has never been demonstrated. Incrimination of LPA and/or one of its receptors could lead to the proposition of new therapeutic agents for the treatment of renal fibrosis that are currently scarce [2]. We have therefore studied LPA and its receptors in an animal model of renal fibrosis: unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO). This model mimics in an accelerated manner the development of renal fibrosis including renal inflammation, fibroblast activation and accumulation of extracellular matrix in the tubulointerstitium (Figure 1, [4]). The results of this study are summarized in Figure 2 and described below (Details of this study can be found in [31]).

Figure 2. Overview of the profibrotic effect of LPA and the LPA1 receptor in unilateral obstruction (UUO)-induced renal fibrosis.

The kidney is composed of filtration units called nephrons. We propose that the antifibrotic effect of LPA1 receptor blockade involves reduction of CTGF secretion by proximal tubular cells which are located in the tubular section of the nephron. (a) LPA1 receptor expression is increased by UUO reaching a maximum after 8 days of obstruction, the day of sacrifice. The expression of the 3 other LPA receptors was not modified, except a slight decrease in the expression of the LPA3 receptor. (b) In parallel, UUO also increases renal LPA production, starting as early as 3 days after obstruction. (c) UUO-induced renal fibrosis was significantly attenuated by LPA1 receptor ablation and LPA1 receptor antagonist (Ki16425) treatment as shown by immunohistochemical analysis and quantification of collagen type III expression. (d) In vitro, on tubular cells, LPA treatment induces the expression and release of the pro-fibrotic cytokine, Connective Tissue growth Factor (CTGF). CTGF secretion induced by LPA seems to be LPA1 receptor dependant, as CTGF secretion is blocked by the LPA1 receptor antagonist (Ki16425). See details in [31]. Abbreviations: Cont, control non-UUO mice; UUO, unilateral ureteral obstruction; WT, wild type mice; KOLPA1, LPA1(−/−) mice; WT+Ki16425, wild type mice treated with the LPA1 receptor antagonist Ki16425.

Confirming a previous report [41], we found that renal LPA receptors are expressed under basal conditions with an expression order of LPA2>LPA3=LPA1>>LPA4 (Figure 2a). UUO significantly induced LPA1 receptor expression while the expression of the three other LPA receptors remained stable, except for a small, but significant decrease, in expression of the LPA3 receptor. This was paralleled by renal LPA production (3.3 fold increase) in conditioned media from kidney explants (Figure 2b). Contro-lateral kidneys exhibited no significant changes in LPA release and LPA receptors expression. This shows that a prerequisite for an action of LPA in fibrosis is met: production of a ligand (LPA) and induction of one of its receptors (the LPA1 receptor). In order to determine whether this induction plays role in the development of renal fibrosis, UUO-induced renal TIF was compared between mice invalidated for the LPA1 receptor (LPA1 (−/−)) and wild type mice (LPA1(+/+))[19, 55]. Interestingly, the development of renal fibrosis was significant attenuated in LPA1(−/−) mice (Figure 2c). This genetic invalidation was confirmed upon the use of the LPA1 receptor antagonist Ki16425 [17, 18]. UUO mice treated with this antagonist closely resembled the LPA1 (−/−) mice (Figure 2c). These observations clearly demonstrated the crucial involvement of LPA and its receptor LPA1 in the etiology of kidney fibrosis [31]. However, the contribution of the different renal cells in this profibrotic effect was less clear.

Since UUO-induced fibrosis is essentially interstitial, without visible glomerular lesions [56, 57], the glomerular (mesangial cell) LPA1 receptor is likely not involved in the effects of LPA on UUO-induced TIF. The other cell types that can be potential targets of LPA in the development of UUO-induced renal fibrosis include tubular- and inflammatory-cells and interstitial fibroblasts. Since it was already known that LPA can participate in intraperitonial accumulation of monocyte/macrophages [58, 59] and that LPA can induce expression of the pro-fibrotic cytokine CTGF in primary culture human fibroblasts [29], we focused the remainder of our studies on the in vitro effects of LPA treatment on tubular cells. In addition, it has been shown that primary culture human proximal tubular cells express the LPA1 receptor [54]. LPA treatment of a mouse epithelial renal cell line MCT [60] induced a rapid increase of the expression of profibrotic cytokine CTGF (Figure 2d). CTGF plays a crucial role in UUO-induced TIF [61, 62], and is involved in the pro-fibrotic activity of TGFβ [6]. This induction was almost completely suppressed by co-treatment with the LPA-receptor antagonist Ki16425 (Figure 2d). Similar observations were previously made in renal fibroblasts and mesangial cells [25, 28, 29], where the action of LPA on CTGF was shown to be mediated by the small GTPase rhoA and the down-stream kinase ROCK [28]. Interestingly, treatments with ROCK-inhibitors have been described to attenuate UUO-induced renal TIF [63], similar to what we observed in LPA1(−/−)- and in Ki16425-treated mice. Altogether, these observations strongly suggested that the pro-fibrotic activity of LPA in kidney could result from a direct action of LPA on kidney cells involving induction of CTGF (Figure 2, [31]).

The metabolic origin of renal LPA remains to be determined. Several enzymes, including phospholipases A1/A2, lysophospholipase D/autotaxin (ATX), glycerol-phosphate acyltransferase, or monoacylglycerol kinase (MAGK), can possibly lead to renal LPA synthesis [64]. The expression and/or the activity of one of these enzymes might be increased in the kidney as an adaptive response to chronic kidney injury induced by UUO. Preliminary data from our laboratory suggest that neither ATX nor MAGK are responsible for the increased synthesis of LPA associated with renal fibrosis, since their expression is rapidly and strongly down-regulated during UUO (data not shown). In rat, UUO was shown to increase the activity of a phosphoethanolamine-specific PLA2 [65]. The involvement of this enzyme in LPA synthesis in the obstructed kidney remains to be explored.

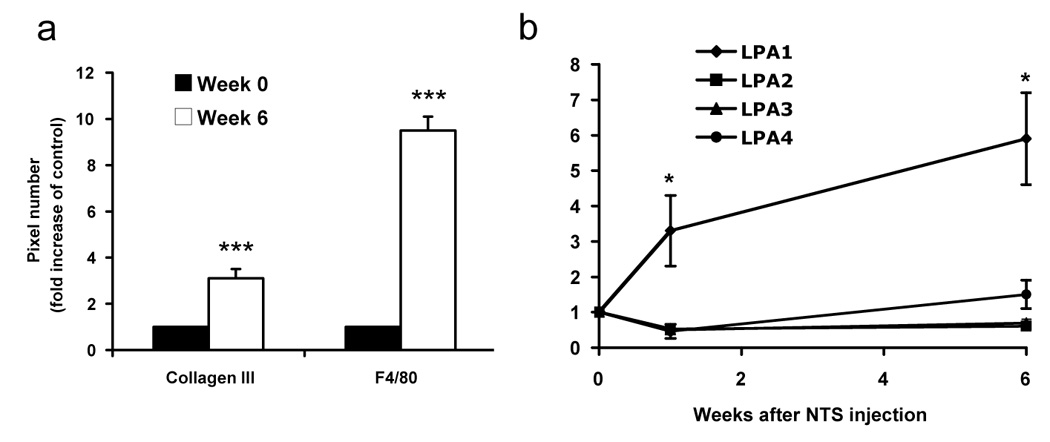

LPA receptor expression in other models of renal fibrosis

Although the UUO model of renal fibrosis mimics the different stages of the development of renal fibrosis, the rapidity by which these lesions are installed does not exactly correspond to the slow progression of human renal disease. The murine model of nephrotoxic serum (NTS) nephritis described by Lloyd CM et al [66], is characterized by a rapid progressive glomerulonephritis followed by the slow appearance of TIF leading after several weeks to progressive renal failure [67]. This model more closely mimics the slow progression of human renal disease. We show here for the first time modification of LPA receptor expression in this chronic model (Figure 3). As previously reported [67], NTS-induced TIF is characterized by an increased expression of fibrosis markers (macrophage infiltration and collagen expression, Figure 3a). Interestingly, renal expression of the LPA1 receptor was significantly increased one and 6 weeks after NTS injection when compared to control mice (respectively 3,3 ±1 and 5,9 ±1,3 fold of control) (Figure 3b). In contrast, the expression of the other LPA receptors was not modified. This suggest, as shown in the UUO model of accelerated renal fibrosis, that LPA and its receptors can play role in the development renal fibrosis originating from glomerulonephritis. An interesting aspect of this model is the fact that this disease is originating from glomerular inflammation. As we discussed above, LPA is inducing important biological effects on glomerular mesangial cells in vitro [45–49]. Therefore blockade of the effects of LPA in this model might modify the progression of disease in both the glomerular- and tubular-compartment. Further studies comparable to those performed with the UUO model [31] of renal fibrosis will be necessary to better understand the role of LPA and its receptors in CKD.

Figure 3. LPA receptor expression in a chronic model of renal fibrosis induced by nephrotoxic serum injection (NTS).

(a) Inflammation and fibrosis increases 6 weeks after NTS injection. Mice were sacrificed at 0 and 6 weeks after NTS injection and kidneys were analyzed for F4/80 (macrophage) and collagen III (fibrosis) expression using immunohistochemistry. The histograms represent computer-assisted analysis of 10 different microscopic fields of a kidney slice (as described in [31]), obtained from 5 different mice. (b) mRNA expression analysis of LPA receptors. NTS induces expression of the LPA1 receptor only. Mice are injected with NTS (time 0). Mice are euthanized at the time of NTS injection and one or six weeks later (n=5). LPA receptor expression was quantified by real time PCR. Comparisons with time 0 were analyzed by the Student-t-test, *, p<0,05.

Conclusion

Using both genetically engineered animals and pharmacological tools a number of laboratories have recently shown that LPA and its LPA1 receptor can play an important role in the development of fibrosis. Mechanisms of the profibrotic action of LPA and the LPA1 receptor in these different tissues involve stimulation of fibroblast migration, increased vascular permeability and CTGF secretion by a number of cells; all events known to be involved in the fibrotic process [7]. These results suggest that the LPA1 receptor could become a promising new therapeutic target in fibrosis.

In the kidney, TGFβ seems to be only moderately involved in the anti-fibrotic effect of LPA1 receptor blockade. This cytokine is one of the most potent pro-fibrotic factors involved in the (renal) fibrotic process. Since TGFβ has many other effects [68], its blockage is not a realistic therapeutic option to reduce renal fibrosis. More recently, it has been proposed that CTGF blockade could represent a promising antifibrotic therapy [61]. Therefore, lowering CTGF production by pharmacological LPA1 receptor blockade might be an interesting opportunity in the treatment of renal fibrosis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the INSERM. Julie Klein and Julien Gonzalez were supported by a grant from the Ministère de l’Education Nationale de la Recherche et de la Technologie (France). We would like to acknowledge the help of Dr Alexandre Bénani for the design of Figure 1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Meguid El Nahas A, Bello AK. Chronic kidney disease: the global challenge. Lancet. 2005;365:331–340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17789-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boor P, Sebekova K, Ostendorf T, Floege J. Treatment targets in renal fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:3391–3407. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strutz F. Potential methods to prevent interstitial fibrosis in renal disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:1989–2001. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.11.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bascands JL, Schanstra JP. Obstructive nephropathy: insights from genetically engineered animals. Kidney Int. 2005;68:925–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwano M, Neilson EG. Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004;13:279–284. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basile DP. The transforming growth factor beta system in kidney disease and repair: recent progress and future directions. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1999;8:21–30. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wynn TA. Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:524–529. doi: 10.1172/JCI31487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watterson KR, Lanning DA, Diegelmann RF, Spiegel S. Regulation of fibroblast functions by lysophospholipid mediators: potential roles in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:607–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz-Ortega M, Bustos C, Plaza JJ, Egido J. Overexpression of extracellular matrix proteins in renal tubulointerstitial cells by platelet-activating factor stimulation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:886–892. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.4.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz-Ortega M, Largo R, Bustos C, Gomez-Garre D, Egido J. Platelet-activating factor stimulates gene expression and synthesis of matrix proteins in cultured rat and human mesangial cells: role of TGF-beta. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1266–1275. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V881266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doi K, Okamoto K, Negishi K, Suzuki Y, Nakao A, Fujita T, Toda A, Yokomizo T, Kita Y, Kihara Y, Ishii S, Shimizu T, Noiri E. Attenuation of folic acid-induced renal inflammatory injury in platelet-activating factor receptor-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1413–1424. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giri SN, Sharma AK, Hyde DM, Wild JS. Amelioration of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis by treatment with the platelet activating factor receptor antagonist WEB 2086 in hamsters. Exp Lung Res. 1995;21:287–307. doi: 10.3109/01902149509068833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuroda K, Morimoto Y, Ogami A, Oyabu T, Nagatomo H, Hirohashi M, Yamato H, Nagafuchi Y, Tanaka I. Phospholipid concentration in lung lavage fluid as biomarker for pulmonary fibrosis. Inhal Toxicol. 2006;18:389–393. doi: 10.1080/08958370500516200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasuda K, Sato A, Nishimura K, Chida K, Hayakawa H. Phospholipid analysis of alveolar macrophages and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid following bleomycin administration to rabbits. Lung. 1994;172:91–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00185080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adrian JE, Poelstra K, Scherphof GL, Meijer DK, van Loenen-Weemaes AM, Reker-Smit C, Morselt HW, Zwiers P, Kamps JA. Effects of a new bioactive lipid-based drug carrier on cultured hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis in bile duct-ligated rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:536–543. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.117945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anliker B, Chun J. Cell surface receptors in lysophospholipid signaling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohta H, Sato K, Murata N, Damirin A, Malchinkhuu E, Kon J, Kimura T, Tobo M, Yamazaki Y, Watanabe T, Yagi M, Sato M, Suzuki R, Murooka H, Sakai T, Nishitoba T, Im DS, Nochi H, Tamoto K, Tomura H, Okajima F. Ki16425, a subtype-selective antagonist for EDG-family lysophosphatidic acid receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:994–1005. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.4.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boucharaba A, Serre CM, Guglielmi J, Bordet JC, Clezardin P, Peyruchaud O. The type 1 lysophosphatidic acid receptor is a target for therapy in bone metastases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9643–9648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600979103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Contos JJ, Fukushima N, Weiner JA, Kaushal D, Chun J. Requirement for the lpA1 lysophosphatidic acid receptor gene in normal suckling behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13384–13389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Contos JJ, Ishii I, Fukushima N, Kingsbury MA, Ye X, Kawamura S, Brown JH, Chun J. Characterization of lpa(2) (Edg4) and lpa(1)/lpa(2) (Edg2/Edg4) lysophosphatidic acid receptor knockout mice: signaling deficits without obvious phenotypic abnormality attributable to lpa(2) Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6921–6929. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6921-6929.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye X, Hama K, Contos JJ, Anliker B, Inoue A, Skinner MK, Suzuki H, Amano T, Kennedy G, Arai H, Aoki J, Chun J. LPA3-mediated lysophosphatidic acid signalling in embryo implantation and spacing. Nature. 2005;435:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature03505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardell SE, Dubin AE, Chun J. Emerging medicinal roles for lysophospholipid signaling. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vial C, Zuniga LM, Cabello-Verrugio C, Canon P, Fadic R, Brandan E. Skeletal muscle cells express the profibrotic cytokine connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2), which induces their dedifferentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/jcp.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chudgar SM, Deng P, Maddala R, Epstein DL, Rao PV. Regulation of connective tissue growth factor expression in the aqueous humor outflow pathway. Mol Vis. 2006;12:1117–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eberlein M, Heusinger-Ribeiro J, Goppelt-Struebe M. Rho-dependent inhibition of the induction of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:1172–1180. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graness A, Giehl K, Goppelt-Struebe M. Differential involvement of the integrin-linked kinase (ILK) in RhoA-dependent rearrangement of F-actin fibers and induction of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) Cell Signal. 2006;18:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graness A, Poli V, Goppelt-Struebe M. STAT3-independent inhibition of lysophosphatidic acid-mediated upregulation of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) by cucurbitacin I. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hahn A, Heusinger-Ribeiro J, Lanz T, Zenkel S, Goppelt-Struebe M. Induction of connective tissue growth factor by activation of heptahelical receptors. Modulation by Rho proteins and the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37429–37435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heusinger-Ribeiro J, Eberlein M, Wahab NA, Goppelt-Struebe M. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in human renal fibroblasts: regulatory roles of RhoA and cAMP. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1853–1861. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1291853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muehlich S, Schneider N, Hinkmann F, Garlichs CD, Goppelt-Struebe M. Induction of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in human endothelial cells by lysophosphatidic acid, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and platelets. Atherosclerosis. 2004;175:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pradere JP, Klein J, Gres S, Guigne C, Neau E, Valet P, Calise D, Chun J, Bascands JL, Saulnier-Blache JS, Schanstra JP. LPA1 receptor activation promotes renal interstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:3110–3118. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiedmaier N, Muller S, Koberle M, Manncke B, Krejci J, Autenrieth IB, Bohn E. Bacteria induce CTGF and CYR61 expression in epithelial cells in a lysophosphatidic acid receptor-dependent manner. Int J Med Microbiol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. Faseb J. 2004;18:816–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kantarci A, Black SA, Xydas CE, Murawel P, Uchida Y, Yucekal-Tuncer B, Atilla G, Emingil G, Uzel MI, Lee A, Firatli E, Sheff M, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE, Trackman PC. Epithelial and connective tissue cell CTGF/CCN2 expression in gingival fibrosis. J Pathol. 2006;210:59–66. doi: 10.1002/path.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ikeda H, Yatomi Y, Yanase M, Satoh H, Nishihara A, Kawabata M, Fujiwara K. Effects of lysophosphatidic acid on proliferation of stellate cells and hepatocytes in culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:436–440. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu J, Zern MA. Hepatic stellate cells: a target for the treatment of liver fibrosis. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:665–672. doi: 10.1007/s005350070045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe N, Ikeda H, Nakamura K, Ohkawa R, Kume Y, Tomiya T, Tejima K, Nishikawa T, Arai M, Yanase M, Aoki J, Arai H, Omata M, Fujiwara K, Yatomi Y. Plasma lysophosphatidic acid level and serum autotoxin activity are increased in liver injury in rats in relation to its severity. Life Sci. 2007;81:1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe N, Ikeda H, Nakamura K, Ohkawa R, Kume Y, Aoki J, Hama K, Okudaira S, Tanaka M, Tomiya T, Yanase M, Tejima K, Nishikawa T, Arai M, Arai H, Omata M, Fujiwara K, Yatomi Y. Both plasma lysophosphatidic acid and serum autotaxin levels are increased in chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:616–623. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225642.90898.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tager AM, Lacamera P, Shea BS, Campanella GS, Selman M, Zhao Z, Polosukhin V, Wain J, Karimi-Shah BA, Kim ND, Hart WK, Pardo A, Blackwell TS, Xu Y, Chun J, Luster AD. The lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA(1) links pulmonary fibrosis to lung injury by mediating fibroblast recruitment and vascular leak. Nat Med. 2007 doi: 10.1038/nm1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Vries B, Matthijsen RA, van Bijnen AA, Wolfs TG, Buurman WA. Lysophosphatidic acid prevents renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibition of apoptosis and complement activation. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:47–56. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63629-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okusa MD, Ye H, Huang L, Sigismund L, Macdonald T, Lynch KR. Selective blockade of lysophosphatidic acid LPA3 receptors reduces murine renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F565–F574. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00023.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sasagawa T, Suzuki K, Shiota T, Kondo T, Okita M. The significance of plasma lysophospholipids in patients with renal failure on hemodialysis. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol(Tokyo) 1998;44:809–818. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.44.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akalaev RN, Abidov AA. Phospholipid composition of erythrocytes in patients with chronic kidney failure. Vopr Med Khim. 1993;39:43–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamanna VS, Bassa BV, Ganji SH, Roh DD. Bioactive lysophospholipids and mesangial cell intracellular signaling pathways: role in the pathobiology of kidney disease. Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:603–613. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levine JS, Koh JS, Triaca V, Lieberthal W. Lysophosphatidic acid: a novel growth and survival factor for renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:F575–F585. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.4.F575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaits F, Salles JP, Chap H. Dual effect of lysophosphatidic acid on proliferation of glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1022–1027. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue CN, Forster HG, Epstein M. Effects of lysophosphatidic acid, a novel lipid mediator, on cytosolic Ca2+ and contractility in cultured rat mesangial cells. Circ Res. 1995;77:888–896. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.5.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inoue CN, Ko YH, Guggino WB, Forster HG, Epstein M. Lysophosphatidic acid and platelet-derived growth factor synergistically stimulate growth of cultured rat mesangial cells. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1997;216:370–379. doi: 10.3181/00379727-216-44184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goppelt-Struebe M, Hahn A, Iwanciw D, Rehm M, Banas B. Regulation of connective tissue growth factor (ccn2; ctgf) gene expression in human mesangial cells: modulation by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) Mol Pathol. 2001;54:176–179. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dixon RJ, Brunskill NJ. Lysophosphatidic acid-induced proliferation in opossum kidney proximal tubular cells: role of PI 3-kinase and ERK. Kidney Int. 1999;56:2064–2075. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dixon RJ, Young K, Brunskill NJ. Lysophosphatidic acid-induced calcium mobilization and proliferation in kidney proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F191–F198. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.2.F191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi JW, Lee-Kwon W, Jeon ES, Kang YJ, Kawano K, Kim HS, Suh PG, Donowitz M, Kim JH. Lysophosphatidic acid induces exocytic trafficking of Na(+)/H(+) exchanger 3 by E3KARP-dependent activation of phospholipase C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1683:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee-Kwon W, Kawano K, Choi JW, Kim JH, Donowitz M. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates brush border Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) activity by increasing its exocytosis by an NHE3 kinase A regulatory protein-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16494–16501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumagai N, Inoue CN, Kondo Y, Iinuma K. Mitogenic action of lysophosphatidic acid in proximal tubular epithelial cells obtained from voided human urine. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;99:561–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simon MF, Daviaud D, Pradere JP, Gres S, Guigne C, Wabitsch M, Chun J, Valet P, Saulnier-Blache JS. Lysophosphatidic acid inhibits adipocyte differentiation via lysophosphatidic acid 1 receptor-dependent down-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14656–14662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412585200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chevalier RL. Obstructive nephropathy: towards biomarker discovery and gene therapy. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:157–168. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klahr S, Morrissey J. Obstructive nephropathy and renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F861–F875. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00362.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koh JS, Lieberthal W, Heydrick S, Levine JS. Lysophosphatidic acid is a major serum noncytokine survival factor for murine macrophages which acts via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:716–727. doi: 10.1172/JCI1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Llodra J, Angeli V, Liu J, Trogan E, Fisher EA, Randolph GJ. Emigration of monocyte-derived cells from atherosclerotic lesions characterizes regressive, but not progressive, plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11779–11784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403259101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haverty TP, Kelly CJ, Hines WH, Amenta PS, Watanabe M, Harper RA, Kefalides NA, Neilson EG. Characterization of a renal tubular epithelial cell line which secretes the autologous target antigen of autoimmune experimental interstitial nephritis. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1359–1368. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yokoi H, Mukoyama M, Nagae T, Mori K, Suganami T, Sawai K, Yoshioka T, Koshikawa M, Nishida T, Takigawa M, Sugawara A, Nakao K. Reduction in connective tissue growth factor by antisense treatment ameliorates renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1430–1440. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000130565.69170.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yokoi H, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Mori K, Nagae T, Makino H, Suganami T, Yahata K, Fujinaga Y, Tanaka I, Nakao K. Role of connective tissue growth factor in fibronectin expression and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F933–F942. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00122.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagatoya K, Moriyama T, Kawada N, Takeji M, Oseto S, Murozono T, Ando A, Imai E, Hori M. Y-27632 prevents tubulointerstitial fibrosis in mouse kidneys with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1684–1695. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moolenaar WH, van Meeteren LA, Giepmans BN. The ins and outs of lysophosphatidic acid signaling. Bioessays. 2004;26:870–881. doi: 10.1002/bies.20081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fukuzaki A, Morrissey J, Klahr S. Enhanced glomerular phospholipase activity in the obstructed kidney. Int Urol Nephrol. 1995;27:783–790. doi: 10.1007/BF02552148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lloyd CM, Minto AW, Dorf ME, Proudfoot A, Wells TN, Salant DJ, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. RANTES and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) play an important role in the inflammatory phase of crescentic nephritis, but only MCP-1 is involved in crescent formation and interstitial fibrosis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1371–1380. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeisberg M, Hanai J, Sugimoto H, Mammoto T, Charytan D, Strutz F, Kalluri R. BMP-7 counteracts TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reverses chronic renal injury. Nat Med. 2003;9:964–968. doi: 10.1038/nm888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, Allen R, Sidman C, Proetzel G, Calvin D, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]