Abstract

Pseudomonas chlororaphis phage 201φ2-1 is a relative of Pseudomonas aeruginosa myovirus φKZ. Phage 201φ2-1 was examined by complete genomic sequencing (316,674 bp), by a comprehensive mass spectrometry survey of its virion proteins and by electron microscopy. Seventy-six proteins, of which at least 69 have homologues in φKZ, were identified by mass spectrometry. Eight proteins, in addition to the major head, tail sheath and tail tube proteins, are abundant in the virion. Electron microscopy of 201φ2-1 revealed a multitude of long, fine fibers apparently decorating the tail sheath protein. Among the less abundant virion proteins are three homologues to RNA polymerase β or β′ subunits. Comparison between the genomes of 201φ2-1 and φKZ revealed substantial conservation of the genome plan, and a large region with an especially high rate of gene replacement. The φKZ-like phages exhibited a two-fold higher rate of divergence than for T4-like phages or host genomes.

Introduction

The large, lytic Pseudomonas myovirus φKZ has recently been the subject of extensive study, including genomic sequencing (280,334 bp), sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS PAGE) of the virion proteins (Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002) and cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) analyses (Fokine et al., 2005, 2007). Interest in this phage and its gene products was partially generated by its potential use in bacteriophage therapy and other biotechnological applications (Briers et al., 2007; Fokine et al., 2007; Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002; Miroshnikov et al. 2006; Paradis-Bleau et al., 2007). The sequence of one φKZ relative, EL, has also been completely determined (211,215 bp; Hertveldt et al., 2005), and 19 other phages have been assigned to the φKZ-like group based on several criteria (Krylov et al., 2007). φKZ and EL are highly diverged from known myoviruses (Hertveldt et al., 2005; Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002). This divergence is such that the identity and function of only a fraction of the φKZ virion proteins (<12.5 %) have been determined (Fokine et al., 2005, 2007; Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002). φKZ is structurally complex; SDS-PAGE of φKZ virions indicated the presence of more than 40 different proteins, five of which were identified by N-terminal sequencing (Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002).

To expand knowledge of the φKZ-like phages, we have undertaken a comprehensive investigation of our recently isolated Pseudomonas chlororaphis phage, 201φ2-1, a member of the φKZ-like phage group (Krylov et al., 2007; Serwer et al., 2004). These studies included complete genomic sequencing of the 316,674 bp 201φ2-1 genome and mass spectrometric (MS) identification of 201φ2-1 virion proteins. The use of MS was essential to enumerate the virion proteins because few were identifiable by sequence comparison. A comprehensive analysis of divergence among the φKZ-like phages revealed a two-fold greater rate of divergence than for cellular or T4 genes. Hence, there is a correspondence between high divergence to other myoviral proteins and a high divergence rate among phiKZ-like phages.

Results and Discussion

Genomic sequence

The genomic sequence of 201φ2-1 is 316,674 bp long, making it the longest phage genome in GenBank (accession number: EU197055). Restriction mapping revealed a circular map. Mobility at high (6V/cm) constant field after pulsed field fractionation revealed a linear genomic DNA molecule. Hence, the genome is circularly permuted like that of φKZ. The 201φ2-1 genome encodes 462 putative proteins and a single tRNA (Leu; anticodon = UAA).

Attempts were made to detect distant homology between 201φ2-1 proteins and the structural and morphogenesis proteins of myoviruses outside the φKZ group by the method that Thomas et al. (2007) used to characterize the newly sequenced 0305φ8-36. This method utilizes Hidden Markov Models developed with the Sequence Alignment and Modeling System (SAM - Hughey and Krogh, 1996; Karplus et al., 1998). The Thomas et al. (2007) models defined protein families spanning many myoviruses for key myoviral structure and morphogenesis proteins. Only two homologues were detected in 201φ2-1 by these models, fewer than for other myoviruses. Detecting sheath and terminase was an exercise in overcoming a high divergence barrier. For example, the sheath model that matched myoviruses sheaths as diverse as T4, P2, and VHML with E < 10−11, matched the established φKZ sheath with E=2. A more sensitive comparison using HHpred was conducted in which an HMM representing all three φKZ-like sheath homologues was compared to the general myoviral sheath model. This improved the confidence to E = 10−9. This indicates that the φKZ-like sheath is homologous to other myoviral sheaths, and that the problem must be high divergence. TheφKZ terminase protein was identified as one of the most divergent branches on the global terminase tree of Serwer et al. (2004). Hence most φKZ-like virion proteins can not be identified by sequence comparison, and those that can are close to the limit of similarity detection.

Mass spectrometry

Since MS provided an extensive amount of information about another large and unusual myovirus, Bacillus thuringiensis phage 0305φ8-36 (Thomas et al., 2007), we applied the same analytical strategy to phage 201φ2-1. Seventy-six proteins were identified in the mature 201φ2-1 virion (Table 1) by capillary HPLC-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS). Two strategies were used for the preparation of samples prior to in-gel digestion and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis (see Methods): conventional SDS-PAGE followed by excision of detected gel bands (Fig. 1), and SDS-PAGE followed by division of the entire lane into seven slices [a technique termed “GeLCMS” (Lasonder et al., 2002)]. As was the case for phage 0305φ8-36 (Thomas et al., 2007), GeLCMS was more efficient at detecting the low-abundance virion proteins, but missed the largest protein, gp276 (253 kDa), apparently due to the failure of this protein to migrate into the sampled gel region. GeLCMS additionally provided a rough estimate of the relative abundance of the different virion proteins through a comparison of the number of identified tandem mass spectra assigned to each protein after normalizing by molecular weight (analogous to “spectrum counting”, Zybailov et al., 2005). This assessment was particularly useful to provide insight into which were the most abundant among several co-migrating proteins.

Table 1.

MS data and homologues for the 201φ2-1 proteins identified by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS.

| Identification by MS1 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gp | M r(kDa) | Unique peptides | Total spectra | Spectra/Mw | % coverage | Function, homologues, paralogues2 |

| A. Proteins of established virion function according to Fokine et al. (2007) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 303 | 77.5 | 22 | 355 | 4.6 | 44 | major sheath protein, KZ429 (63% over 693); EL6 (21% over 707) |

| 2005 | 82.4 | 22 | 696 | 8.4 | 38 | major capsid protein, KZ120 (64% over 749); EL78 (20% over 325) |

| 2765 | 251.8 | 23 | 34 | 0.1 | 10 | cell-puncturing device, KZ181 (33% over 2387); KZ144 (45% over 187); EL183 (22% over 270) |

|

| ||||||

| B. RNA polymerase-related virion proteins | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 139 | 49.6 | 8 | 34 | 0.7 | 24 | RNA polymerase, beta’ subunit, KZ80 (56% over 449); EL44 (23% over 447) |

| 273/274 | 173.4 | 24 | 87 | 0.5 | 19 | RNA polymerase, beta subunit, KZ178 (53% over 1548); EL186 (23% over 1142); EL187 (26% over 356) |

| 275 | 62.7 | 8 | 27 | 0.4 | 15 | RNA polymerase, beta subunit KZ180 (68% over 490); EL184 (32% over 491) |

|

| ||||||

| C. Other virion proteins | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 273 | 62.3 | 8 | 47 | 0.8 | 21 | KZ26 (54% over 549), EL9 (29% over 540) |

| 286 | 101.8 | 11 | 28 | 0.3 | 15 | KZ27 (47% over 899); EL8 (26% over 898) |

| 29 | 35.7 | 4 | 24 | 0.7 | 15 | KZ28 (43% over 320); EL7 (21% over 181) |

| 32 | 32.1 | 10 | 149 | 4.6 | 51 | KZ30 (75% over 290); EL5 (20% over 217) |

| 36 | 47.9 | 4 | 9 | 0.2 | 11 | KZ32 (55% over 410); EL13 (27% over 373) |

| 48 | 29.9 | 4 | 17 | 0.6 | 16 | KZ34 (40% over 267) |

| 49 | 12.3 | 5 | 43 | 3.5 | 53 | |

| 73 | 31.2 | 3 | 10 | 0.3 | 11 | KZ42 (61% over 274); EL14 (23% over 213) |

| 81 | 14.7 | 4 | 4 | 0.3 | 25 | KZ49 (44% over 135); EL20 (34% over 49) |

| 98 | 41.9 | 5 | 19 | 0.5 | 17 | KZ52 (51% over 362) |

| 138 | 31.9 | 6 | 20 | 0.6 | 23 | KZ79 (38% over 286) |

| 145 | 49.0 | 9 | 34 | 0.7 | 26 | ligase, KZ84 (34% over 434); EL52 (19% over 348) |

| 146 | 15.9 | 7 | 63 | 4.0 | 74 | KZ85 (33% over 145) |

| 1487 | 47.5 | 9 | 38 | 0.8 (1.2) | 23 | KZ86 (24% over 378) |

| 149 | 109 | 8 | 19 | 0.17 | 10 | KZ87 (52% over 971); EL56 (25% over 981) |

| 150 | 41 | 2 | 6 | 0.15 | 5 | KZ88 (56% over 344); EL57 (28% over 334) |

| 1515,7 | 44.4 | 13 | 107 | 2.4 (4.0) | 29 | KZ89 (53% over 406); EL58 (28% over 225) |

| 152 | 34.4 | 12 | 121 | 3.5 | 43 | KZ90 (47% over 294) |

| 153 | 20.8 | 4 | 14 | 0.7 | 22 | KZ91 (51% over 170) |

| 154 | 49.1 | 8 | 28 | 0.6 | 22 | KZ92 (34% over 356) |

| 1557 | 65.6 | 17 | 121 | 1.8 (3.8) | 31 | KZ94 (26% over 305), paralogue family b |

| 1567 | 43.2 | 9 | 70 | 1.6 (2.6) | 25 | KZ94 (30% over 410), paralogue family b |

| 1577 | 53 | 9 | 62 | 1.2 (1.9) | 27 | KZ94 (22% over 380), paralogue family b |

| 158 | 41.6 | 2 | 4 | 0.1 | 5 | KZ96 (29% over 356) |

| 1597 | 97.4 | 10 | 133 | 1.4 (4.0) | 15 | KZ97 (27% over 540) |

| 162 | 54.8 | 3 | 13 | 0.2 | 6 | KZ99 (53% over 465); EL69 (21% over 259) |

| 164 | 51.9 | 2 | 3 | 0.06 | 5 | KZ101 (42% over 457); EL71 (28% over 395) |

| 1937 | 42.4 | 13 | 188 | 4.4 (7.0) | 33 | |

| 198 | 20.3 | 4 | 13 | 0.6 | 25 | KZ119 (52% over 178) |

| 211 | 15.9 | 2 | 6 | 0.4 | 17 | KZ126 (33% over 142) |

| 212 | 32.4 | 3 | 6 | 0.2 | 12 | KZ127 (37% over 291) |

| 213 | 84 | 5 | 11 | 0.1 | 8 | KZ128 (49% over 725); EL104 (26% over 599) |

| 214 | 102.3 | 8 | 21 | 0.2 | 15 | KZ129 (51% over 880); EL103 (20% over 323) |

| 215 | 48.9 | 4 | 18 | 0.4 | 18 | KZ130 (53% over 439); EL112 (23% over 299) |

| 216 | 79.7 | 9 | 43 | 0.5 | 17 | KZ131 (38% over 782); EL113 (27% over 199) (paralogue family a)7 |

| 217 | 11.8 | 6 | 45 | 3.8 | 76 | KZ132 (48% over 83); EL116 (27% over 77); (paralogue family a)7 |

| 218 | 50.7 | 6 | 14 | 0.3 | 14 | KZ133 (37% over 464); EL115 (18% over 264)(paralogue family a)7 |

| 219 | 50.4 | 5 | 9 | 0.2 | 16 | KZ134 (35% over 471); EL114 (23% over 247) (paralogue family a)7 |

| 220 | 48.5 | 3 | 10 | 0.2 | 9 | KZ 135 (38% over 347); EL115 (20% over 268)(paralogue family a)7 |

| 224 | 32.5 | 7 | 34 | 1.1 | 26 | KZ139 (66% over 292); EL106 (28% over 278) |

| 226 | 16.3 | 4 | 9 | 0.6 | 30 | KZ103 (26% over 97) |

| 2276 | 14.6 | 3 | 11 | 0.7 | 21 | KZ142 (31% over129) |

| 228 | 23.9 | 6 | 42 | 1.8 | 30 | KZ143 (46% over 181) |

| 229 | 29.1 | 1 | 1 | 0.03 | 5 | KZ144 (47% over 65) |

| 230 | 155.8 | 50 | 606 | 3.9 | 59 | KZ145 (51% over 222); KZ146 (27% over 760); EL156 (33% over 812) |

| 233 | 25.4 | 5 | 18 | 0.7 | 26 | KZ149 (62% over 221); EL175 (32% over 224) |

| 2388 | 35.7 | 14 | 76 | 2.1 | 41 | KZ153 (27% over 307) |

| 243 | 50.8 | 15 | 110 | 2.2 | 44 | KZ157 (53% over 442); EL169 (25% over 404) |

| 245 | 23.2 | 1 | 1 | 0.04 | 6 | KZ161 (42% over 203); EL168 (27% over 201) |

| 246N7 | 66.4 | 3 | 14 | (0.7) | 17 | KZ162 (24% over 330), paralogue family b |

| 246C7 | 19 | 197 | 3.0 (4.4) | 58 | ||

| 247 | 44.5 | 9 | 36 | 0.8 | 32 | KZ163 (45% over 375), paralogue family b |

| 261 | 40.8 | 12 | 25 | 0.6 | 42 | KZ174 (38% over 380) |

| 2686 | 31.9 | 5 | 36 | 1.1 | 18 | KZ175 (55% over 268); EL192 (35% over 207) |

| 269 | 27.1 | 1 | 5 | 0.2 | 5 | KZ176 (63% over 240); EL191 (25% over 242) |

| 2718 | 70.2 | 8 | 51 | 0.7 | 18 | KZ177 (41% over 489) |

| 277 | 59.0 | 3 | 5 | 0.07 | 4 | KZ182 (64% over 668); EL182 (23% over 352) |

| 280 | 21.1 | 2 | 18 | 0.9 | 14 | KZ184 (59% over 120) |

| 296 | 16.5 | 5 | 17 | 1.0 | 44 | exonuclease; KZ199 (61% over 139) |

| 298 | 70.1 | 4 | 10 | 0.1 | 7 | KZ201 (27% over 635) |

| 299 | 12.9 | 4 | 28 | 2.2 | 37 | KZ202 (25% over 99) |

| 300 | 81.1 | 7 | 17 | 0.2 | 12 | helicase of the SNF2/RAD54 family; KZ203 (51% over 710); EL166 (33% over 500) |

| 313 | 13.3 | 3 | 11 | 0.8 | 38 | KZ244 (24% over 119) |

| 382 | 12 | 2 | 24 | 2.0 | 37 | |

| 439 | 31.7 | 5 | 17 | 0.5 | 25 | |

| 440 | 32.1 | 6 | 36 | 1.1 | 32 | |

| 441 | 72.4 | 12 | 44 | 0.6 | 34 | |

| 442 | 35.5 | 6 | 19 | 0.5 | 20 | |

| 452 | 26.5 | 2 | 10 | 0.4 | 9 | KZ83 (25% over 243); EL155 (27% over 104), paralogue family c |

| 455 | 87.6 | 16 | 62 | 0.7 | 21 | KZ303 (28% over 406) |

| 456 | 45 | 6 | 27 | 0.6 | 18 | EL155 (26% over 191); KZ83 (26% over 183), paralogue family c |

All proteins had a protein identity probability of 100%, as determined by Scaffold (Proteome Software), with the exception of gp164 (99%) and gp229 (96%). Results displayed were obtained from a combined data set of the GeLCMS analysis, with the exception of gp276 which was only detected in analysis of an individual gel band (see text).

Homologues were determined using Psi-Blast and BlastP (% identities over the homologous region are provided). The best matching φKZ and EL homologue for each 201φ2-1 protein is listed. Paralogue families are as follows: paralogue family a refers to a domain found in 201φ2-1 gp216, 217, 218, 219, 220. A homologous domain exists in φKZ gp131, 132, 133, 134 and 135 and EL gp113, 114 and 115; paralogue family b refers to a domain found in 201φ2-1 gp155, 156, 157, 246, 247. Homologous domains exist in φKZ gp93, 94, 95, 162 and 163; paralogue family c refers to a domain found in 201φ2-1 gps 456 and 452. Homologous domains exists in φKZ gp83 and EL gp155.

An N-terminal peptide lacking only the initiator methionine was identified using semi-tryptic analysis.

KZ refers to φKZ.

N-terminus is expected to be processed as the φKZ homologue is processed. Although no semi-tryptic fragments were found to define the mature ends, there is also a lack of peptide coverage in the N-terminal region that would be consistent with processing.

A mature N-terminus containing the initiator methionine was confirmed by semi-tryptic analysis.

Gel analysis indicated that the protein is processed consistent with a lack of MS sequence coverage in the N-terminal region of these sequences, except for gp246N which lacks MS coverage of the C terminal region. The exact positions of the processed ends are unknown. The normalized spectrum count in parentheses was calculated using the apparent molecular weight of the processed form (Fig. 1).

Semi-tryptic analysis indicated removal of 63 and 60 N-terminal residues from gp238 and gp271, respectively.

Figure 1.

Virion proteins of 201φ2-1 separated by SDS-PAGE in a Bio-Rad Tris-HCl-buffered gradient gel (8 to 16% polyacrylamide). Proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Molecular weights corresponding to the Precision Plus Protein Standard (Bio-Rad) are marked to the left of the sample lane. Identities of 201φ2-1 gene products assigned to bands are indicated to the right. In several cases, more than one protein was present in a gel band; these proteins are listed from highest to lowest relative abundance, left to right, based on spectrum counting (see Methods). Proteins migrating significantly faster than predicted from their molecular weights are marked with “*” or “†” based on whether N- or C-terminal sequences, respectively, lacked MS sequence coverage.

Virion proteins with homologues of established function

The functions of three 201φ2-1 virion proteins, gp200, 30 and 276, were assigned based on their sequence similarities to φKZ proteins with established functions. Gp200 is the homologue of the major head proteins of φKZ (KZ120) and EL (EL78) (Fokine et al., 2005; Hertveldt et al., 2005; Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002). N-terminal sequence analysis has shown that the head proteins of φKZ and EL are processed (Hertveldt et al., 2005; Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002). In our MS analysis of 201φ2-1 gp200, no peptides were detected N-terminal to residue 157, suggesting that gp200 is also processed. However, the MS results did not identify a specific cleavage site in 201φ2-1 gp200.

Gp30 is the 201φ2-1 homologue of the major sheath proteins of φKZ (KZ29; Krylov et al., 2007) and EL (EL6; Hertveldt et al., 2005). As expected based on function, the 201φ2-1 major head protein and sheath protein were identified in two of the three most intensely staining SDS-PAGE bands (Fig. 1). Evidence was obtained from the MS analysis of gp30 that only the N-terminal methionine had been removed from the mature sheath protein.

The third 201φ2-1 virion protein of assigned function is the large, low-abundance protein gp276. Its φKZ homologue (φKZ gp181) is thought to form the cell-puncturing device (Krylov et al., 2007).

Other abundant virion proteins

In addition to the major proteins for the head and sheath, several 201φ2-1 proteins of unknown function had molecular weight normalized spectrum counts of greater than 3.0 in the GeLCMS experiment (spectra/Mw, Table 1 section C). By comparison, the average spectrum count for all proteins in Table 1 was 1.0, and the average for proteins with spectrum counts under 3.0 was 0.6. Among the proteins with high spectrum counts, gp32, 146, 152, 193, 230 and 246, along with apparently processed forms of gp151, 155 and 159, were also identified in intense 1D gel bands (Fig. 1). These nine are candidates for proteins of greater than average abundance, and therefore probably present in more than 6, 12, or 18 molecules per virion, which is characteristic of the average T4 virion protein (e.g. forming the baseplate, neck or tail fibers). Of these nine 201φ2-1 proteins, gp32 is the best candidate for the tail tube protein. Tail tube and sheath are expected in the same number of molecules per virion, and gp32 shared the same spectrum count (4.6) as the sheath. This degree of correspondence has to be taken with the realization that estmation of abundance from spectrum counts is subject to substantial uncertainty (Zybailov et al., 2005). For example, the spectrum counts of the sheath and major capsid protein were 4.6 and 8.5, and the number of molecules per virion expected from φKZ are 246 and 1560, respectively (Fokine et al., 2005, 2007). Hence, we chose not to interpret abundance from spectrum counts more closely than a factor of three. Assignment of gp32 as the tail tube is additionally supported by its size which is typical of myoviral tail tube proteins, and the position of its gene immediately downstream of that for the tail sheath.

Other notable properties of this set of apparently abundant 201φ2-1 virion proteins were also observed. 1) Phage 201φ2-1 gp230 has an unusually high molecular weight (156 kDa) for an abundant phage virion protein and is a fusion of homologues of φKZ gp145 and gp146. φKZ gp145 has previously been recognized as an abundant virion protein (Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002). Gp230 is probably incorporated in a virion structure with fibrous character, as evidenced by the presence of sequence motifs in gp230 that match motifs in known fibrous proteins, including bacterial adhesions and “collagen-like” phage fiber proteins (data not shown). 2) Phage 201φ2-1 gp246 is post-translationally cleaved into two mature virion proteins, each detected in a separate SDS-PAGE band (Fig. 1). 3) Gp193 is the only abundant 201φ2-1 virion protein without an identifiable φKZ homologue. It is probably processed, based on the lack of MS sequence coverage of its N-terminal region.

Electron microscopy

There are several abundant proteins in the 201φ2-1 virion in addition to the standard major myovirus proteins (main head, tail sheath and tail tube proteins). Thus, we examined phage particles more closely by electron microscopy (EM), in an attempt to visualize previously unnoticed structures that could account for the existence of some of these additional abundant proteins. As anticipated from the large number of 201φ2-1 homologues to φKZ proteins (Table 1), EM showed that 201φ2-1 has a large capsid and tail of similar dimensions and morphology to φKZ (Fokine et al., 2007; Krylov et al., 2007). 201φ2-1 also has a conspicuous neck structure and a complex baseplate. Fibers extending from the baseplate in a similar arrangement to those of φKZ are illustrated in the inset to the middle panel of Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Electron micrographs of 201φ2-1. Black short tailed arrows in all panels highlight several fine fibers projecting from the tail sheaths or heads of 201φ2-1 virions. (Top panel) Two particles of purified 201φ2-1 that were treated with DNAase immediately prior to being negatively stained with uranyl acetate. (Middle panel) Negatively stained 201φ2-1 without prior DNAase treatment. The arrow marked “a” indicates a possible strand of DNA. The inset image highlights a well stained baseplate from a virion. (Bottom panel) Cryo-EM image of 201φ2-1, without DNAase treatment. The white short tailed arrow highlights a particle (at the image edge) that has a contracted tail sheath and an empty head. The large white arrow highlights gasseous bubbles which formed in the head despite the use of low-dose techniques (see text). In the top and middle rows, large black arrows highlight particles that copurified with 201φ2-1 virions. In the bottom row, the large gray arrow highlights contamination on the cryo-EM specimen. All three scale bars = 100 nm.

Many fibers were seen around the 201φ2-1 baseplate, tail sheath, and head. We had some concern that some of these, particularly some very long strands (e.g. Fig. 2, middle panel “a”), might be DNA. The top panel of Fig. 2 is a DNAase I treated control, illustrating that there are abundant proteinaceous fibers attached to the 201φ2-1 virion, including head fibers (Fig. 2, top right panel). In the top left panel of Fig. 2 fibers appear to have been swept towards the top right of the panel, perhaps by fluid flow during sample preparation. In this arrangement it appears that there are fibers attached to the sheath itself, and that they extend over 100 nm from the point of attachment. Sheath fibers of this type have not been reported previously for φKZ. However, other phages belonging to the φKZ-like group have been reported to have fibers around their sheath, but these fibers were described as “a fibrous network extending from the baseplate and wrapped around the tail sheath” (Krylov et al., 2007) rather than projecting from the sheath as found here.

Precedents exist for fibers attached to the sheath in the non-φKZ-like phages PBS1 and PMB12 (Bramucci et al., 1977; Eiserling, 1967). However, the sheath fibers of PBS1 and PMB12 (called contraction fibers) appear straighter than the fibers observed in 201φ2-1. Diversity exists in the appearance of the tail-associated fibers among the φKZ-like phages (Krylov et al., 2007). It is unclear which, if any, of the other φKZ-like isolates also have fibers attached to the sheath. However, the cryo-EM reconstruction of the φKZ sheath shows small outward projections from each sheath subunit (Fokine et al., 2007). We speculate that these projections are the attachment points for either sheath fiber proteins or their anchors.

The 201φ2-1 fibers probably account for some of the functionally unassigned abundant proteins in this phage (Table 1). Another potential location for such proteins also appears inside the head. There is a 201φ2-1 head structure visualized by cryo-EM (Fig. 2, bottom panel, long white arrow) that is extremely sensitive to the electron beam. Despite the use of low-dose techniques, this feature immediately produced gaseous bubbles upon electron irradiation. This feature is likely similar to the cylindrical inner body described for the φKZ head; the composition and function of the inner body of φKZ is unknown (Fokine et al., 2005; Krylov et al., 1984). The inner body is a potential location for virion proteins of both high and low abundance, including some of the more than 25 proteins reported to be present in the φKZ head (Fokine et al., 2005).

Finally, EM showed abundant pleiomorphic particles that co-purified with 201φ2-1 virions (Fig. 2, top and middle panels). These are likely to be outer membrane vesicles of the type documented by Lavigne et al. (2006) associated with phage particles. Confirming this, host ompF and an outer membrane lipoprotein were found in the MS data (not shown). It is possible that some of the prospective virion proteins are instead components of these particles.

RNA polymerase-related virion proteins

Three 201φ2-1 proteins detected by MS (gp 139, 273/274, and 275) were homologues of either β or β′ subunits of bacterial RNA polymerase (RNAP). These assignments were first suggested by weak blastp or psi-blast matches, and then confirmed with E values equal or better than 10−5 using profile methods SAM or HHpred. The genes encoding gp 273/274 and 275 are clustered in the 201φ2-1 genome immediately upstream of the gene encoding the cell-puncturing device, gp276. Phage 201φ2-1 ORFs 273 and 274 are homologous to EL187 and EL186, respectively. Although ORFs 273 and 274 were predicted to be independent ORFs by GeneMark, they actually belong to a single gene interrupted by a mobile intron. Evidence implying that gp 273/274 forms a single protein was obtained by detecting peptides corresponding to both ORFs 273 and 274 in the band of a single large polypeptide on the SDS-PAGE gel (Fig. 1). Examination of the sequence between ORFs 273 and 274 showed that it is homologous to the sequences of several mobile introns identified in φKZ (data not shown) but the φKZ homologue to 201φ2-1 ORFs 273 and 274 (KZ178) is not interrupted.

By comparison to other RNA polymerases, 201φ2-1 gp273/274 appears to be a full-length RNAP β subunit. In addition, two other 201φ2-1 virion-associated proteins (gp275 and 139) are homologous to RNAP subunits. Gp275 is homologous to the N-terminal portion of the RNAP β′ subunit while gp139 is homologous to the C-terminal portion of this subunit. A region in gp275 matches the corresponding motif in RNAP β′ at all but one position (TADFDGD instead of NADFDGD) and contains the three aspartic acid residues necessary for the chelation of Mg2+ in the active center of the enzyme (Zaychikov et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 1999). The division of the β′ gene into two genes is analogous to the subdivision of rpoC to rpoC1 and rpoC2 in cyanobacteria (Xie et al. 1989).

It is unusual to find subunits of multi-subunit RNAP associated with phage virions. However, there is at least one precedent for a virion-associated multi-subunit RNAP—in the morphologically complex B. subtilis myovirus PBS2 (Clark et al., 1974). Sequence information for the PBS2 RNAP subunits is not available. The subunits of the PBS2 virion RNAP were of unconventional sizes (80, 76, 58 and 48 kDa)(Clark et al., 1974). By comparison, the β and β′ subunits of bacteria typically have high molecular weights, e.g. 151 and 155 kDa, respectively, in E. coli (Sweetser et al., 1987). We hypothesize that the 201φ2-1 virion RNAP subunits are injected into the cell for expression of phage genes, as suggested for PBS2 (Clark et al., 1974). While the fully-assembled RNAP is too large to pass through the tail tube, the separate subunits may be able to do so. It is unknown whether other 201φ2-1 virion-associated proteins contribute to the functioning RNAP or if some host RNAP subunits are recruited to form a functioning complex.

Although the phage preparation was CsCl banded twice to avoid casual contamination, there is still the possibility that the RNAP may have adhered to or been incorporated into the virions in some non-functional way. Other virion-associated proteins that seem out of place in the virion include a helicase, ligase, and an exonuclease (ORFs 296, 300, Table 1). A factor in considering the functional implications of the RNAP in the virion is the observation that there is a second RNAP encoded in the 201φ2-1 genome (Fig. 3). The second RNAP is not virion-associated and is therefore presumably expressed after infection in the manner usually expected for a phage-encoded RNAP. The non-virion RNAP genes also have φKZ and EL homologues. They similarly encode a β subunit and divided β′ subunits (listed in GenBank entry EU197055). To maintain virion-associated and non-virion-associated paralogues implies functional specialization and supplies some justification for the idea that there may be a function requiring one of them to be in the virion. There are therefore unique problems to solve in understanding the φKZ-like transcriptional program with respect to the use of the two RNAPs and how other subunits or mechanisms may be required to guide specificity of gene expression.

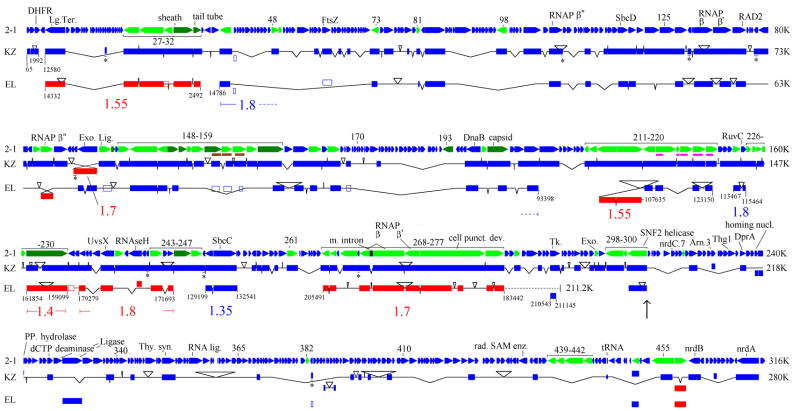

Figure 3.

Genome map of 201φ2-1 in comparison to φKZ and EL. Color coding in the 201φ2-1 track: green - gene product detected by MS (with abundant proteins in dark green); brown and magenta - two families of paralogues. Color coding in the KZ and EL tracks: blue - same orientation as the homologous 201φ2-1 gene, red - opposite orientation. Solid boxes are matching segments in the style of tblastx (see methods). An asterisk below an inderlined section of a φKZ match indicates protein sequence similarity within a newly predicted gene in φKZ (Supplementary Table 1). Hollow boxes indicate similarity detection requiring a profile method. The names of individual φKZ or EL genes found within the matching segments are in GenBank EU197055. The connectors between matching segments are inflected to indicate the amount of DNA inserted or deleted relative to 201φ2-1. Coordinates within the φKZ or EL genomes are given at the ends of chains of matches. The average 201φ2-1:EL/201φ2-1: φKZ divergence over segments delimited by inversion points is given in the same color as the chain of matches defining the segment and located below the EL track. The black dotted line for EL portrays the end of its genome relative to its rightmost major matching segment. Boxes not connected into chains map to uncorrelated positions in the different genomes. The vertical arrow indicates the beginning of the region discussed for its high rate of gene exchange in the text. Abbreviations are Lg. Ter (large subunit of terminase), RNAP (RNA polymerase), Exo. (exonuclease), Lig. (ligase), m. intron (mobile intron), Tk (thymidine kinase), Thy. syn. (thymidylate synthetase), rad. SAM enz. (radical SAM enzyme).

Three-way comparison of the 201φ2-1 genome with φKZ and EL

An analysis was conducted to determine how the virion-encoding genes were organized within the 201φ2-1 genome, and how this organization compared to φKZ and EL. Blastp detected 69 virion-encoding and 167 total 201φ2-1 genes that were homologous to φKZ genes and 39 virion-encoding and 61 total that were homologous to EL genes. A graphical comparison (Fig. 3) was designed to illustrate the similarity in genomic organization. The genes marked in green are the virion-encoding genes, and are among the most conserved in their organization. Matches joined into a chain in Fig. 3 represent genes in the same order along the chromosome, and to a first approximation are assumed to represent genes retained during vertical descent from a single common ancestral phage. Whatever deviation from simple vertical descent from a single common ancestor may have occured, we expect that the large numbers of genes in the comparison will produce an average divergence reflective of the history of most of the genes. Matches outside of the chains are homologues found at unrelated positions in the different genomes, and are presumed to be independent acquisitions by horizontal transfer.

Phage 201φ2-1 and φKZ are therefore relatively closely related and many of their genes appear to have descended from a single common ancestral phage. In contrast, the large rearranged segments in EL (Hertveldt et al., 2005) suggest the possibility that each segment has a different ancestral relationship between EL and the other two phages. However, the 201φ2-1:EL divergence is consistently about 1.5-fold higher than 201φ2-1:φKZ divergence in each of these segments (Fig. 3). Similarly, at the nucleotide level blastn detects a string of matches between the genomes of 201φ2-1 and φKZ (not shown), but no similarity at the nucleotide level between 201φ2-1 and EL. If the EL segmental inversion pattern reflects mosaicism, the exchanges will have occurred between φKZ and EL soon after they initially diverged. Therefore, EL can be considered as having a single common ancestor with 201φ2-1 and φKZ such that this conceptual ancestor represents an averaged split time among the conserved genes. Hertveldt et al. (2005) noted that φKZ has 36.8% G+C, and EL has 49.3% G+C. Phage 201φ2-1 has 45.3% G+C. Therefore the peculiar low GC composition of φKZ has probably developed since the relatively recent split with 201φ2-1. The major rearrangements in EL, and one small inversion inφKZ, appear to be inversions in place. This may indicate a tendency of the φKZ-like phage replication system to cause inversions without the involvement of horizontal transfer. Extrapolating the tendency for inversion even deeper into the history of this lineage may explain the tendency for transcription orientation to frequently invert. Switches in transcription orientation are observed even within blocks of genes maintaining functional clustering. For example, there are eight changes of transcriptional orientation within blocks of genes encoding virion proteins (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 illustrates that many of the genes in common between 201φ2-1 and φKZ that are missing in EL are opposite a gap in EL. Others are opposite apparently nonhomologous DNA and are likely to have been replaced with different genes. However, EL is sufficiently diverged from 201φ2-1 and φKZ that some EL homologues may not yet have been recognized. The encoded proteins that did match to EL homologues were mostly over 50% identical between 201φ2-1 and φKZ. Many of the proteins without recognized EL homologues were in the 25–40% identity range between 201φ2-1 and φKZ. Many of those would not be recognizable by blastp after another 1.5-fold divergence. A few more EL homologues were identified by either psi-blast in the 3 genomes alone, or by making HMM models of arrays of paralogues (Fig. 3, hollow boxes).

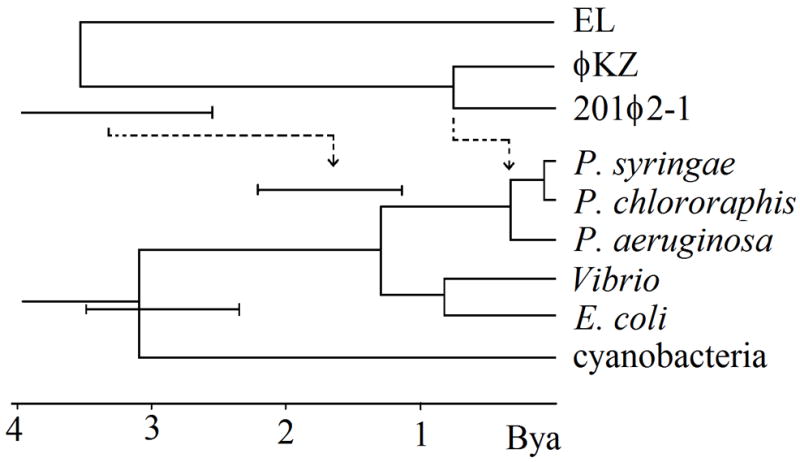

Time of origin

Since there was a suspicion of high divergence within the φKZ lineage undermining comparison to other myoviral proteins, we sought to measure the divergence rate in the core of vertically descending genes described above. This requires an estimate of the split times, which we take as a first guess to be the P. aeruginosa:P. chlororaphis split for 201φ2-1:φKZ, and some time no later than the origin of Pseudomonas for the 201φ2-1:EL split. It also requires correcting the raw divergence values for the effect of saturation, meaning the degree to which changes on top of other changes shorten the apparent divergence of more distantly related sequences. To estimate the ages of the φKZ and EL ancestors, 201φ2-1:φKZ or 201φ2-1:EL divergence was compared to divergence of homologous genes with known split times. By comparing to a split at a known time in a reference lineage at a similar depth of divergence, we expect saturation effects to mostly cancel.

For 201φ2-1:φKZ, phage gene divergence was compared to the homologous host gene divergence, except that P. syringae was used to stand in for the unsequenced P. chlororaphis genome (Table 2). An rRNA tree was constructed to estimate the P. aeruginosa:P. syringae split to be 330 Mya (Fig. 4). For phage-specific genes, there is one phage lineage, the T4-like lineage, that has been set to an absolute time scale (Fileé et al. 2006), and used as a standard ruler for other phage lineages (Hardies et al., 2007). The T4:KVP40 split from this lineage was used as a reference, and assumed to represent the split time of the host bacterial species (E. coli:Vibrio parahaemolyticus) at 0.8 Bya (Battistuzzi et al., 2004). In the cases where both T4 lineage and cellular references were available for the same genes, the T4 lineage diverged only 25% faster than the cellular lineage (Table 2 and Table 3). This small difference was ignored. If all versions of each gene diverge at the same rates, and the phages split at the same time as their hosts, then the 201φ2-1:φKZ divergences should be 41% of the T4:KVP40 divergences. Instead, the 201φ2-1:φKZ divergences are on average 80% of T4:KVP40, and twice P. aeruginosa:P. syringae (Table 2). Hence, either 201φ2-1 split from φKZ well before their respective hosts split, or φKZ-like phages systematically diverge twice as fast as cellular and T4 lineage genes.

Table 2.

Divergence values useful for estimating age of 201φ2-1: φKZ split

| 201φ2-1: φKZ | T4:KVP40 (0.8 Bya viral ref.) | P. aeruginosa: P. syringae (0.33 Bya host ref.)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| large terminase | 41% | 46% | |

| capsid | 36% | 40% | |

| sheath | 37% | 52% | |

| tail tube | 25% | 44% | |

| UvsX | 31% | 44% | 16% |

| SbcC | 58% | 59% | 56% |

| SbcD | 43% | 60% | 34% |

| tRNA Leu | 32% | - | 18% |

| DnaB | 41% | 53%b | 15% |

| NrdA | 37% | 42% | 17% |

| NrdB | 36% | 48% | 19% |

| Thy. Synthetase | 40% | 59% | - |

| DHFR | 67% | - | 27% |

| Thy. Kinase | 68% | 57% | 25% |

|

| |||

| ave. (col. 1/ref.) | 0.8 | 2.0 | |

Strains used were P. aeruginosa PAO1 and P. syringae pv. syringae B728a.

Helicase domain of gp41.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree relating the split times of the φKZ-like phages to the history of relevant bacterial species. The host tree was derived from rRNA sequence (see methods). The φKZ-like phage tree is shown either with an equal rate assumption (solid lines), or as adjusted for a two-fold greater divergence rate (dashed lines).

Table 3.

Divergence values useful for estimating age of 201φ2-1:EL split

| 201φ2-1: φEL | T4:P-SSM2 (2.8 Bya viral ref.) | P. aeruginosa: cyanobacteria (2.8 Bya host ref.)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| large terminase | 75% | 65% | |

| capsid | 80% | 65% | |

| sheath | 79% | 63% | |

| tail tube | 80% | 65% | |

| UvsX | 75% | 66% | 41% |

| SbcC | 70% | 66% | 54% |

| SbcD | 70% | 68% | 65% |

| DnaB | 77% | 56% | 56% |

|

| |||

| ave. (Col. 1/ref.) | 1.2 | 1.6 | |

Cyanobacterial reference strain was Synechococcus sp. WH5701

For the older EL split, the closest reference point in the T4 lineage is the T4:cyano-T4 split. Cyanobacteria:P. aeruginosa cellular genes were used as the cellular reference (Table 3). There is a large range of uncertainty in the actual time of this split as indicated by the rRNA result (Fig. 4), and also in the results of Battistuzzi et al. (2004) obtained using a large set of protein data. However, the minimum age is considered to be 2.3 Bya. The 201φ2-1:EL divergences exceed the cyanobacterial and cyano-T4 divergences (Table 3). Without incorporating a faster divergence rate for the φKZ-like phages, the resulting 201φ2-1:EL split time is implausibly ancient. First, φKZ-like phages originating at this time should have descended into many different genera of both gram negative and gram positive bacteria. More importantly, the relationship of some of these genes (terminase and tail sheath discussed above and capsid by structural comparison (Fokine et al., 2005)) argues that the common ancestor with the other myoviruses is much earlier than the 201φ2-1:EL split. So the 201φ2-1:EL split itself should not be close to the origin of life on earth. By accepting the two-fold faster divergence rate for the φKZ-like phages, the 201φ2-1:EL split is brought down to a time whereby it could have occurred in the early Pseudomonas lineage, thus alleviating both of those discrepancies (Fig. 4, dashed lines).

Accounting for the extra genes of 201φ2-1

The φKZ-like phages have evolved not only by residue replacments but also by processes that dramatically alter their overall content of genes. We sought to characterize and quantitate those processes. Whereas the extra length of φKZ compared to EL is mostly in one region, the extra genome length of 201φ2-1 compared to φKZ is distributed at multiple sites, often in modules packed with small genes all transcribed in the same orientation (Fig. 3). The final predicted set of 462 genes in 201φ2-1 compares to 306 genes predicted in φKZ by Mesyanzhinov et al. (2002). Our prediction scheme annotates another 63 small reading frames in φKZ in addition to those previously reported (Supplementary Table 1). The newly annotated φKZ frames are of a similar quality to the previously annotated frames in the same size range as evidenced by the following observation. Blastp matches with 201φ2-1 validated the same fraction (19%) in both sets. Of all the open reading frames initially predicted for 201φ2-1, only eight have been subsequently discounted because they fail to pack cleanly into their respective operons and/or have no recognizable ribosome binding sites. Hence, we expect only a few false positives in the 201φ2-1 predicted genes. This leaves 93 more genes predicted in 201φ2-1 to account for the extra 36 kb of genome length. The very smallest and therefore most ambiguous category (under 100 codons) is not in excess in 201φ2-1. The frame excess in 201φ2-1 is mostly accounted for by an excess of genes of 100–200 codons, but there is an excess of 23 genes predicted with more than 200 codons and four predicted with more than 500 codons.

Rate of horizontal transfer

Insertions, deletions, and substitutions relative to φKZ in the leftmost 72% of the 201φ2-1 map are distributed like those in other comparisons that have been analyzed in detail (e.g. Hardies et al., 2007) and will not be discussed further here. However, the rightmost 28% of the 201φ2-1 map appears to plunge into a more tentative relationship with φKZ. Although the region is dominated by 153 genes with no similarity to φKZ, there is a string of 16 sparsely spaced φKZ homologues in the same genomic order. We take the homologous genes remaining in order to be related through the same common ancestor for 201φ2-1 and φKZ as discussed above for the leftmost 72% of the map. Besides the 16 homologues in order, there are eight more genes in this region homologous to φKZ genes located at uncorrelated places in the φKZ genome. These were apparently acquired independently by each phage by horizontal transfer (Fig. 3). Reinforcing this interpretation, three of these also match to EL homologues, which map to yet different uncorrelated positions in the EL genome. These three apparently independently acquired genes do not conform to the 1.5:1 divergence ratios established above for the other genes shared by all three phages. Several other genes in this region (nrdC.7, Arn.3, DprA) are in common with the T4 lineage. All are highly divergent from any sequenced T4-like phage, therefore a recent date of transfer can not be established. Both the paucity of identifiable orthologues and the concentration of identifiable horizontal transfers in this region suggest that the 153 non-φKZ homologous genes represent replacement by horizontal exchange.

In this particularly volatile region, the rate of gene replacement can be estimated by fitting the residual number of unreplaced genes to a Poisson distribution. Since there are 122 genes in the region in φKZ and 177 in 201φ2-1, the common ancestor presumably had at least 122. Sixteen of 122 genes remain unreplaced; the divergence time is 2 × 0.33 Byr. The probability of loss per 100 Myr is therefore 0.3 [from 16/122 = e−2(3.3x)], and the average residence time before loss is 330 Myr. One of the uncertainties in this estimate is the assumption that genes in this region are lost with equal probability. If the 16 homologues remaining between 201φ2-1 and φKZ are more strongly held than the ones that were lost, then the estimated rate of replacement of the ones that were lost would be higher.

Summary

The source of length differences among the φKZ-like genomes appears to be mainly expansion or contraction of arrays of small genes located at several sites in the genome. Core genomic segments like those described for the T4 lineage (Miller et al., 2003; Comeau et al., 2007) appear to be floating within those arrays, and sometimes subjected to inversion. The MS survey reveals several of these core segments to be composed of clusters of virion protein-encoding genes. Hence, these genomes can be viewed as evolving roughly like T4 genomes, except for the unusually large number of small non-core genes. Several proteins with unanticipated functions, including an RNAP, a helicase, a ligase, and an exonuclease, were identified as virion proteins by MS. The genes for these are clustered with other virion-encoding genes, reinforcing the case that association of these proteins with the virion is meaningful. Establishing homology between the core φKZ-like genes and genes of other myoviruses has been difficult, such that several of the anticipated functional modules are still not found, including a replicative module, a baseplate module, or a tail fiber module. A contributing factor appears to be that the φKZ-like phages are diverging about twice as fast as other phages, thus deepening the divergence barrier that has to be spanned during any sequence comparison. Acquisition of more φKZ-like sequences should empower more sensitive HMM-HMM comparative methods and ultimately sort out which of the φKZ-like proteins are truly novel from those that are highly divergent.

Materials and Methods

Sequencing the 201φ2-1 genome

Pseudomonas chlororaphis phage 201φ2-1 was propagated as previously described, with the exception that glucose was omitted from the media (Serwer et al., 2004). Phage DNA was extracted as described previously (Serwer et al., 2007), with the exception that the freeze-thawing step prior to enzymatic degradation of host RNA and DNA was omitted. Phage 201φ2-1 DNA was included in a mixture of four other phage genomic DNAs totaling 0.8 Mb and sequenced by pyrosequencing (Margulies et al., 2005) by 454 Life Sciences (Branford, CT). This is the same sequencing reaction in which we validated the accuracy of 454’s assigned quality values by confirming over 200,000 bp with dideoxy terminator sequencing (Thomas et al., 2007). The single 201φ2-1 contig (316,674 bp) returned by 454 Life Sciences had a redundancy > 50, and was identified by matching it to the dideoxy shotgun sequence data (~14.5 kb) obtained in a genome sequence survey (Serwer et al., 2004). Primer-directed sequencing was conducted in all regions where low quality values were assigned in the 454 data, resulting in only one base change to the original pyrosequencing contig. Quality assessment of all final bases was > 60, indicating an expectation of < 1 error/106 bases.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The 201φ2-1 phage genome has been deposited in GenBank under the accession no. EU197055.

Genome analyses

Genome analyses were performed as previously described (Thomas et al., 2007), with the exception that homologues to 201φ2-1 proteins were also investigated using HHpred (Söding, 2005; Söding et al., 2005). Fig. 3 was modified from the output of a computer program named b36 chains, which is a variation of tblastx described in Hardies et al. (2007). Divergence of individual loci was calculated as 100 - % identity within the region matched by blastp. Divergence ratios were then averaged over all matches within chains of genes defined in Fig. 3, and added to the figure. The rRNA tree in Fig. 4 was constructed using PAML (Yang, 1997), with the Tamura and Nei (1993) saturation correction and fitting of transition/transversion and shape factors by maximum likelihood.

Phage purification

Stocks of phage 201φ2-1 were prepared in 0.15% agarose overlay in Petri plates (Serwer et al., 2004). The agarose-containing overlay was almost liquid; hence it was harvested without the addition of buffer. This suspension was centrifuged (5000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C) in a JA rotor in a Beckman Avanti J-25 centrifuge. The resulting supernatant was decanted (titer was ~2 × 1011 pfu/ml) and incubated in the presence of DNAase (final concentration 100 μg/ml) and RNAase (final concentration 100 μg/ml) for 1 h at 30 °C. A CsCl step gradient was poured with all steps in buffer composed of 0.01 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 0.001 M MgCl2. The steps had CsCl at the following densities (and volumes in parentheses); 1.59 g/ml (0.75 ml), 1.52 g/ml (0.75 ml), 1.41 g/ml (1.2 ml), 1.30 g/ml (1.5 ml) and 1.21 g/ml (1.8 ml). The phage suspension (5.8 ml) was pipetted on the top of this gradient and spun at 33,000 rpm for 3 h at 18 °C in an SW41 rotor (Beckman Coulter Optima LE-80K ultracentrifuge). The sample was further purified by buoyant density gradient centrifugation (16 h at 42,000 rpm and 10 °C in a SW55Ti rotor). The resulting phage band had a buoyant density of 1.37 g/ml and a titer of 1.3 × 1012 pfu/ml. The phage suspension was dialyzed against three changes of 0.2 M NaCl, 0.01 M Tris-HCl, 0.05 M MgCl2 at 4 °C.

Identification of virion proteins by mass spectrometry

SDS-PAGE of purified phage particles, followed by capillary HPLC-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectra (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS), were performed as described previously (Thomas et al., 2007). Briefly, two strategies were used to analyze 201φ2-1 virion proteins. For the first strategy, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on a gel that was run to completion and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Individual gel bands were excised, digested in situ with trypsin, and the resulting peptides were analyzed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. For other experiments, an SDS-PAGE gel was run for 20 min. and the 1.5-cm region of the gel that contained the partially separated proteins was excised into seven slices before in-gel digestion and MS analysis. This method is referred to as GeLCMS (Lasonder et al., 2002). Assignment of tandem MS data to tryptic peptides encoded by 201φ2-1 ORFs was as described previously (Thomas et al., 2007). Searches considering “semi-tryptic” cleavages in some cases were able to identify the mature N-terminus (Table 1). We additionally searched every subsequence in all six frames of greater than 9 codons between stop codons. No matches to MS-detected peptides were found outside of the predicted genes. A rough estimate of the relative abundance of the different virion proteins was obtained by a method analogous to “spectrum counting” described by Zybailov et al. (2005). The search results for all slices of each sample were combined into one data set and processed by Scaffold (Proteome Software). The number of spectra assigned to each protein at ≥ 95% confidence was normalized by protein molecular weight (Table 1). For ordering the proteins by abundance in Fig. 1, spectrum counts only within the excised band indicated were tallied.

Electron microscopy

Purified 201φ2-1 (8 μl) was treated with 1 μl (1 unit) of RQ1 DNAase (Promega) and 1μl RQ1 10X reaction buffer for 10 min. at ~35 °C. With or without DNAase treatment, 3.5 to 4 μl of reaction volume was placed on a carbon-coated copper grid, washed with deionized H2O, stained with 3.5 μl of 1% uranyl acetate for 20 sec., and allowed to air dry. The specimen was blotted with filter paper between each step. For cryo-EM, a similar volume (without DNAase treatment) was placed on a holey carbon-coated copper grid, blotted to make thin, and plunge frozen in liquid ethane with an FEI Vitrobot vitrification device (Hillsboro, Oregon, USA). The specimen was kept frozen in a Gatan 626 cryoholder (Pleasanton, California, USA). Electron images were recorded on a FEI Tecnai F30 Transmission Electron Microscope (Hillsboro, Oregon, USA). Cryo-EM images were recorded via low-dose methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from The Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation, the Welch Foundation (AQ-764) and the National Institutes of Health (GM24365). PSS and DMB acknowledge institutional support. Mass spectral analyses were performed in the UTHSCSA Institutional Mass Spectrometry Laboratory. Electron microscopy was performed in the BYU Microscopy Lab. We thank Gurneet Kohli for contributing to the pulsed field analysis. We thank the UTHSCSA Bioinformatics Center for assistance with computational aspects of the project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Battistuzzi FU, Feijao A, Hedges SB. A genomic timescale of prokaryote evolution: insights into the origin of methaongenesis, phototrophy, and the colonization of land. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramucci MG, Keggins KM, Lovett PS. Bacteriophage PMB12 conversion of the sporulation defect in RNA polymerase mutants of Bacillus subtilis. J Virol. 1977;24:194–200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.24.1.194-200.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briers Y, Volckaert G, Cornelissen A, Lagaert S, Michiels CW, Hertveldt K, Lavigne R. Muralytic activity and modular structure or the endolysins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophages φKZ and EL. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:1334–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Losick R, Pero J. New RNA polymerase from Bacillus subtilis infected with phage PBS2. Nature. 1974;252:21–24. doi: 10.1038/252021a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comeau A, Bertrand C, Letarov A, Tétart F, Krisch H. Modular architecture of the T4 phage superfamily: A conserved core genome and a plastic periphery. Virology. 2007;362:384–396. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiserling FA. The structure of Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage PBS1. J Ultrastruct Res. 1967;17:342–347. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(67)80053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filée J, Bapteste E, Susko E, Krisch HM. A selective barrier to horizontal gene transfer in the T4-type bacteriophages that has preserved a core genome with the viral replication and structural genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1688–1696. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokine A, Battisti A, Bowman V, Efimov A, Kurochkina L, Chipman P, Mesyanzhinov V, Rossmann M. CryoEM study of the Pseudomonas bacteriophage φKZ. Structure. 2007;15:1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokine A, Kostyuchenko VA, Efimov AV, Kurochkina LP, Sykilinda NN, Robben J, Volckaert G, Hoenger A, Chipman PR, Battisti AJ, Rossmann MG, Mesyanzhinov VV. A three-dimensional cryo-electron microscopy structure of the bacteriophage φKZ head. J Mol Biol. 2005;352:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertveldt K, Lavigne R, Pleteneva E, Sernova N, Kurochkina L, Korchevskii R, Robben J, Mesyanzhinov V, Krylov VN, Volckaert G. Genome comparison of Pseudomonas aeruginosa large phages. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:536–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughey R, Krogh A. Hidden Markov models for sequence analysis: extension and analysis of the basic method. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:95–107. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus K, Barrett C, Hughey R. Hidden Markov models for detecting remote protein homologies. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:846–856. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.10.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov VN, Smirnova TA, Minenkova IB, Plotnilova TG, Zhazikov IZ, Khrenova EA. Pseudomonas bacteriophage φKZ contains an inner body in its capsid. Can J Microbiol. 1984;30:758–762. doi: 10.1139/m84-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov VN, Dela Cruz DM, Hertveldt K, Ackermann HW. φKZ-like viruses”, a proposed new genus of myovirus bacteriophages. Arch Virol. 2007;152:1955–1959. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-1037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasonder E, Ishihama Y, Andersen JS, Vermunt AMW, Pain A, Sauerwein RW, Eling WMC, Hall N, Waters AP, Stunnenberg HG, Mann M. Analysis of the Plasmodium falciparum proteome by high-accuracy mass spectrometry. Nature. 2002;419:537–542. doi: 10.1038/nature01111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne R, Noben JP, Hertveldt K, Ceyssens PJ, Briers Y, Dumont D, Roucourt B, Krylov VN, Mesyanzhinov VV, Robben J, Volckaert G. The structural proteome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage phiKMV. Microbiology. 2006;152:529–534. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28431-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesyanzhinov VV, Robben J, Grymonprez B, Kostyuchenko VA, Bourkaltseva MV, Sykilinda NN, Krylov VN, Volckaert G. The genome of bacteriophage φKZ of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Mol Biol. 2002;317:1–19. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ES, Kutter E, Mosig G, Arisaka F, Kunisawa T, Ruger W. Bacteriophage T4 Genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:86–156. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.1.86-156.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miroshnikov KA, Faizullina NM, Sykilinda NN, Mesyanzhinov VV. Properties of the endolytic transglycosylase encoded by gene 144 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage phiKZ. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2006;71:300–305. doi: 10.1134/s0006297906030102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis-Bleau C, Cloutier I, Lemieux L, Sanschagrin F, Laroche J, Auger M, Garnier A, Levesque RC. Peptidoglycan lytic activity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage φKZ gp144 lytic transglycosylase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;266:201–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwer P, Hayes SJ, Thomas J, Griess GA, Hardies SC. Rapid determination of genomic DNA length for new bacteriophages. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:1896–1902. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwer P, Hayes SJ, Zaman S, Lieman K, Rolando M, Hardies SC. Improved isolation of undersampled bacteriophages: finding of distant terminase genes. Virology. 2004;329:412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söding J. Protein homology detection by HMM-HMM comparison. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:951–960. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söding J, Biegert A, Lupas AN. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W244–W248. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetser D, Nonet M, Young RA. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic RNA polymerases have homologous core subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1192–1196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JA, Hardies SC, Rolando M, Hayes SJ, Lieman K, Carroll CA, Weintraub ST, Serwer P. Complete genomic sequence and mass spectrometric analysis of highly diverse, atypical Bacillus thuringiensis phage 0305phi8-36. Virology. 2007;368:405–421. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W-Q, Jäger K, Potts M. Cyanobacterial RNA polymerase genes rpoC1 and rpoC2 correspond to rpoC of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1967–1973. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.4.1967-1973.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaychikov E, Martin E, Denissova L, Kozlov M, Markovtsov V, Kashlev M, Heumann H, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A, Mustaev A. Mapping of catalytic residues in the RNA polymerase active centre. Science. 1996;273:107–109. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Campbell EA, Minakhin L, Richter C, Severinov K, Darst SA. Crystal Structure of Thermus aquaticus Core RNA polymerase at 3.3 A resolution. Cell. 1999;98:811–824. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81515-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zybailov B, Coleman M, Florens L, Washburn M. Correlation of relative abundance ratios derived from peptide ion chromatograms and spectrum counting for quantitative proteomic analysis using stable isotope labeling. Anal Chem. 2005;77:6218–6224. doi: 10.1021/ac050846r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.