INTRODUCTION

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a proliferative vascular disorder affecting low birth-weight infants. Although effective diagnostic and treatment criteria have been established through the Cryotherapy for ROP (CRYO-ROP)1 and Early Treatment for ROP (ETROP)2 studies, ROP remains a leading cause of childhood blindness throughout the world. It has become a growing problem in middle-income countries, as improvements in neonatal services have increased premature infant survival rates.3,4 Although more infants require ROP surveillance, the availability of ophthalmologists willing to examine at-risk infants is limited. A recent American Academy of Ophthalmology survey showed that only 50% of retinal specialists and pediatric ophthalmologists are managing ROP, and that nearly 25% plan to stop because of issues such as logistical difficulties, medicolegal liability, and financial concerns.5

Store-and-forward telemedicine is a technology with potential to improve the delivery, quality, and accessibility of health care.6 ROP telemedicine strategies have been examined by capturing retinal images and transmitting them to experts for evaluation. Previous studies have shown that remote interpretation of wide-angle retinal images has very high accuracy and reliability for detecting clinically-significant ROP,7–14 and that a trained neonatal nurse can capture images of adequate diagnostic quality.15,16

Although well-known image capture protocols have been developed for radiological studies and ophthalmic diseases such as diabetic retinopathy,17 there is no analogous standard protocol for ROP imaging. Prior studies have generally involved interpretation of multiple images from each retina.8–16 Alternative simpler ROP screening methods involving remote interpretation of single wide-angle retinal images may provide clinical benefits while decreasing costs, particularly if photos were captured by trained non-ophthalmic personnel in areas where time and ophthalmologist availability are limited.15,16,18–20 This is especially true because the number of at-risk infants is large, whereas the requirement for surgical intervention is relatively low. In particular: (1) Results from the ETROP study indicate that treatment-requiring disease is characterized by presence of plus disease or stage III ROP in zone I, regardless of the number of clock hours of peripheral disease.2 In principle, these findings should be visible in a single wide-angle posterior pole photograph. (2) Retinal imaging has been shown to be associated with less physiological stress for infants than indirect ophthalmoscopy.21 Single-image telemedicine examinations might further decrease the incidence of systemic complications, while improving the efficiency of image capture and interpretation.22 (3) It is technically easier to capture a single posterior image than a series of multiple peripheral images, especially from small infants with narrow palpebral fissures.7,11

This study compares the performance of single-image and multiple-image telemedicine interpretations, using primary outcome measures of recommended follow-up interval, presence of plus disease, presence of type-2 or worse ROP, and presence of visible peripheral ROP. All study images were captured by a trained neonatal nurse. Telemedicine interpretations by three retinal specialist graders are compared to a reference standard of dilated indirect ophthalmoscopy by one of two pediatric ophthalmologists. This data set has been used in two previous studies which analyzed diagnostic accuracy, inter-grader reliability, and intra-grader reliability.15,16

METHODS

Nurse Training and Telemedicine System Design

A neonatal nurse was trained to capture wide-angle retinal images using a commercially available device (RetCam-II; Clarity Medical Systems, Pleasanton, CA).15,16 A store-and-forward ROP telemedicine application was developed by the authors (LW, MFC). It included a secure database system (SQL 2005; Microsoft, Redmond, WA); a module allowing the nurse to upload clinical data and images; and a web-based interface for expert interpretation.

Ophthalmoscopic Examination and Retinal Imaging

Infants hospitalized in the Columbia University Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) from November 1, 2005 though October 31, 2006 were included if they met criteria for ROP examination,23,24 and if their parents gave informed consent for participation. Patients were excluded if they had structural ocular anomalies, if they had previously received laser or other surgical ROP treatment, or if their neonatologist considered them to be unstable for examination.

Each study patient underwent two sequential procedures under topical anesthesia at the NICU bedside: (1) One of two experienced pediatric ophthalmologists (SAK, MFC) performed dilated ophthalmoscopic examination according to standard protocols.23,24 Both ophthalmologists were certified investigators in the ETROP study. Findings were documented according to international classification standards.25,26 (2) The study nurse (OC) independently captured up to 5 digital images from each eye, according to a formal study protocol. Posterior, nasal, and temporal retinal images were captured bilaterally, along with up to 2 additional images per eye if felt by the nurse photographer to contribute diagnostic value. The nurse selected the best images, and uploaded them to the telemedicine database. No patients were excluded because of poor image quality or inability to capture photographs.

Study data were obtained at up to two sessions: (1) 31–33 weeks post-menstrual age PMA), in order to represent the time at which initial examinations are performed;23,24 and (2) 35–37 weeks PMA, in order to represent a time when clinically-significant disease occurs, while minimizing the number of study infants lost to hospital discharge or laser photocoagulation.

Telemedical Examination

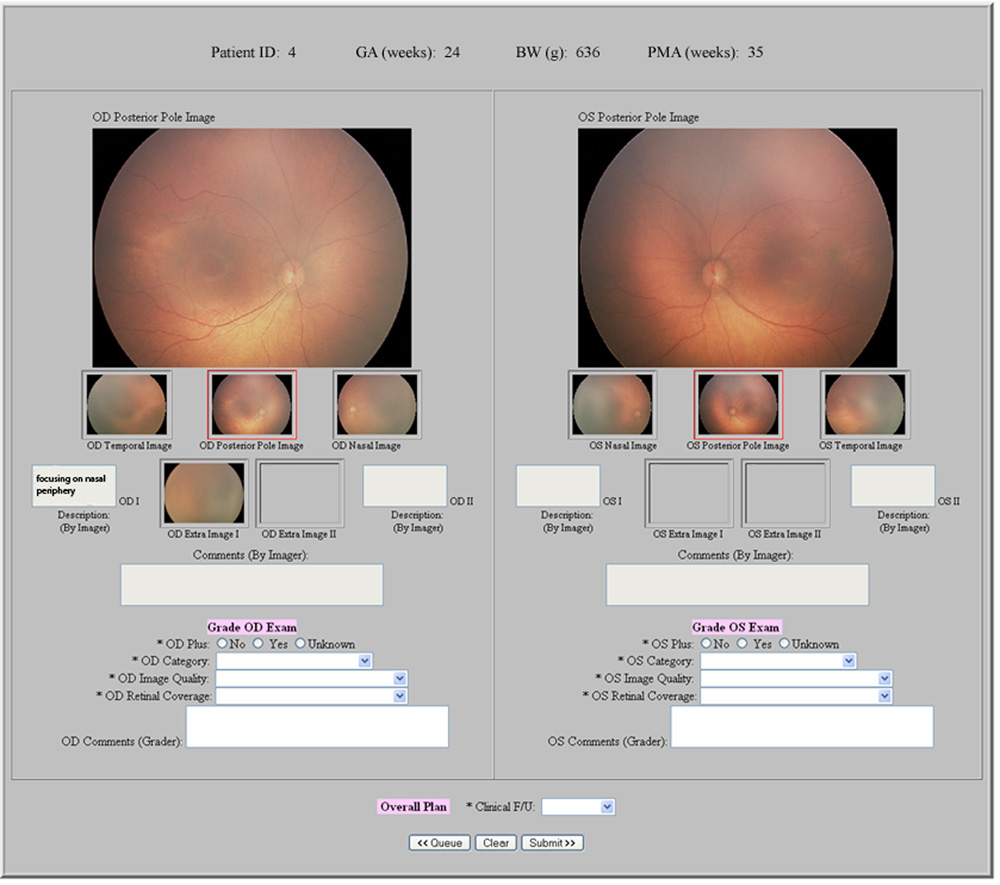

Single-image and multiple-image telemedicine exams were independently performed by three experienced retinal specialist graders (TCL, DJW, AMB) using the web-based system (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Birth weight, gestational age, and PMA at exam were displayed for each infant. During single-image examinations, posterior images of both retinas were displayed side-by-side. Graders were asked about presence of plus disease, type-2 or worse ROP, and visible peripheral ROP in each eye; and about recommended follow-up interval for each infant. During multiple-image examinations, all images of each eye were displayed side-by-side. Graders were asked about presence of plus disease in each eye, recommended follow-up interval in each infant, and disease classification in each eye based on a previously-described system1,2,13–16,25: (1) No ROP; (2) Mild ROP, defined as ROP less than type-2 disease; (3) Type-2 ROP (zone I, stage 1 or 2, without plus disease, or zone II, stage 3, without plus disease); or (4) Treatment-requiring ROP, defined as type-1 ROP (zone I, any stage, with plus disease; zone I, stage 3, without plus disease; or zone II, stage 2 or 3, with plus disease) or worse.

Figure 1. Web-based telemedicine system for single-image examinations for retinopathy of prematurity (ROP).

A wide-angle posterior image of each retina is displayed for graders.

Figure 2. Web-based telemedicine system for multiple-image examinations for retinopathy of prematurity (ROP).

Wide-angle posterior, nasal, and temporal images of each retina are displayed for graders, along with up to 2 additional images per eye if felt by nurse photographer to be of diagnostic value.

For every response, graders were permitted to submit an “unknown” diagnosis if they were uncomfortable providing an answer based on the information provided. To decrease potential bias from imperfect intra-grader reliability when the same images are reviewed at different times,14–16 the multiple-image exam for each patient was performed immediately after the single-image exam. To prohibit alteration of original entries, the telemedicine system prevented graders from returning to the single-image page after responses were submitted.

Data Analysis

Follow-up intervals recommended by graders after single-image, multiple-image, and ophthalmoscopic examinations were tabulated. The number and percentage of follow-up intervals recommended after each exam modality that were longer, equal, and shorter than those recommended after other exam modalities were calculated. Follow-up time distributions were compared using the paired nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test for each grader separately.

Sensitivity and specificity of single-image and multiple-image examinations by each grader were calculated for ability to detect infants requiring follow-up in <2 weeks and those requiring follow-up in <1 week; and for ability to detect visible peripheral ROP, type-2 or worse ROP, and plus disease. Multiple-image examinations were considered to show visible peripheral ROP if they were classified as either mild, type-2, or treatment-requiring ROP. All responses were compared against a reference standard of dilated ophthalmoscopy. The McNemar test was used to statistically compare sensitivities and specificities for single-image and multiple-image exams performed by the same grader, and for the same examinations between different graders.

Analysis was performed separately for examinations at 31–33 weeks PMA, and for those at 35–37 weeks PMA. Diagnosis and follow-up intervals of “unknown” were excluded from analysis so as not to penalize graders who were uncomfortable providing responses, but were tabulated for each grader. All analysis was performed with statistical software (SPSS 15.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was considered to be two-sided p<0.05.

RESULTS

Study Population and Examinations

The characteristics and demographic features of the study population have previously been described.16 Briefly, 67 infants participated in the study, of whom 21 (31.3%) were imaged only at 31–33 weeks PMA, 10 (14.9%) were imaged only at 35–37 weeks PMA, and 36 (53.7%) were imaged at both sessions. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize examination results, from an overall total of 248 study eyes. Diagnosis and follow-up distributions were significantly different p<0.001) between 31–33 weeks and 35–37 weeks PMA for all 3 examination modalities.

Table 1.

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) diagnosis assigned after single-image and multiple-image telemedicine examinations by three retinal specialist graders, and after ophthalmoscopic examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist.

| Diagnoses | 31–33 Weeks PMA n (%) |

35–37 Weeks PMA n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Image Exam (3 graders) | ||

| No visible peripheral ROP | 338 (88.0) | 322 (89.4) |

| Visible peripheral ROP | 11 (2.9) | 25 (6.9) |

| Unknown | 35 (9.1) | 13 (3.6) |

| Multiple-Image Exam (3 graders) | ||

| No ROP | 179 (46.6) | 139 (38.6) |

| Mild ROP | 100 (26.0) | 104 (28.9) |

| Type-2 ROP | 19 (4.9) | 33 (9.2) |

| Treatment Requiring ROP | 10 (2.6) | 70 (19.4) |

| Unknown | 76 (19.8) | 14 (3.9) |

| Ophthalmoscopic Exam (1 grader) | ||

| No ROP | 80 (62.5) | 44 (36.7) |

| Mild ROP | 41 (32.0) | 50 (41.7) |

| Type-2 ROP | 7 (5.5) | 14 (11.7) |

| Treatment Requiring ROP | 0 (0.0) | 12 (10.0) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Study examinations were performed at 31–33 weeks and/or 35–37 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA). Distributions were significantly different (p<0.001) between 31–33 weeks and 35–37 weeks PMA for all 3 examination modalities.

Table 2.

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) follow-up intervals recommended after single-image and multiple-image telemedicine examinations by three retinal specialist graders, and after ophthalmoscopic examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist.

| Recommended Follow-Up Intervals | 31–33 Weeks PMA n (%) |

35–37 Weeks PMA n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Image Exam (3 graders) | ||

| ≥2 Weeks | 81 (42.2) | 84 (46.7) |

| 1 Week | 85 (44.3) | 55 (30.6) |

| <1 Week | 26 (13.5) | 41 (22.8) |

| Multiple-Image Exam (3 graders) | ||

| ≥2 Weeks | 75 (39.1) | 83 (46.1) |

| 1 Week | 85 (44.3) | 50 (27.8) |

| <1 Week | 28 (14.6) | 11 (6.1) |

| Treat | 4 (2.1) | 36 (20.0) |

| Ophthalmoscopic Exam (1 grader) | ||

| ≥2 Weeks | 46 (71.9) | 40 (66.7) |

| 1 Week | 17 (26.6) | 8 (13.3) |

| <1 Week | 1 (1.6) | 6 (10.0) |

| Treat | 0 (0.0) | 6 (10.0) |

Study examinations were performed at 31–33 weeks and/or 35–37 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA). Distributions were significantly different (p<0.001) between 31–33 weeks and 35–37 weeks PMA for all 3 examination modalities.

Comparison of Recommended Follow-Up Intervals

Figure 3 displays comparisons of recommended follow-up intervals based on single-image, multiple-image, and ophthalmoscopic examinations by the three pooled graders. For Graders A and C, recommended follow-up intervals were significantly shorter by both single-image and multiple-image telemedicine exams than by ophthalmoscopy at both 31–33 weeks and 35–37 weeks PMA (p=0.049 for Grader C at 31–33 weeks, p<0.001 for all others). For Grader recommended follow-up intervals by single-image and multiple-image telemedicine exams were shorter than by ophthalmoscopy, but these differences were not statistically-significant.

Figure 3. Graphical comparison of recommended follow-up intervals by single-image, multiple-image, and ophthalmoscopic examinations for retinopathy of prematurity.

Exams were performed at 31–33 weeks and 35–37 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA). Results are displayed as percentage of infants, for single-image and multiple-image examinations vs. ophthalmoscopic examinations.

*At both 31–33 weeks and 35–37 weeks PMA, there were no significant differences between the “single-image exam vs. ophthalmoscopy” follow-up interval distribution and the “multiple-image exam vs. ophthalmoscopy” follow-up distribution.

When compared to each other, single-image and multiple-image exam follow-up times were identical 80.6% of the time at 35–37 weeks PMA (Figure 4). For Graders A and B, there were no significant differences in recommended follow-up intervals between single-image and multiple-image exams at either 31–33 weeks or 35–37 weeks PMA. For Grader C, the recommended follow-up intervals by single-image exam were significantly longer than by multiple-image exam at 31–33 weeks and 35–37 weeks PMA (p<0.001, p=0.002 respectively).

Figure 4. Graphical comparison of recommended follow-up intervals by single-image vs. multiple-image telemedicine examinations for retinopathy of prematurity.

Exams were performed at 31–33 weeks and 35–37 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA). Results are displayed as percentage of infants.

*At both 31–33 weeks and 35–37 weeks PMA, there was a significant difference (p<0.001) between the “single-image exam vs. multiple-image exam” follow-up distribution and those shown in Figure 3 (“single-image exam vs. ophthalmoscopy” and “multiple-image exam vs. ophthalmoscopy”).

Sensitivity and Specificity of Single-Image and Multiple-Image Telemedical Exams

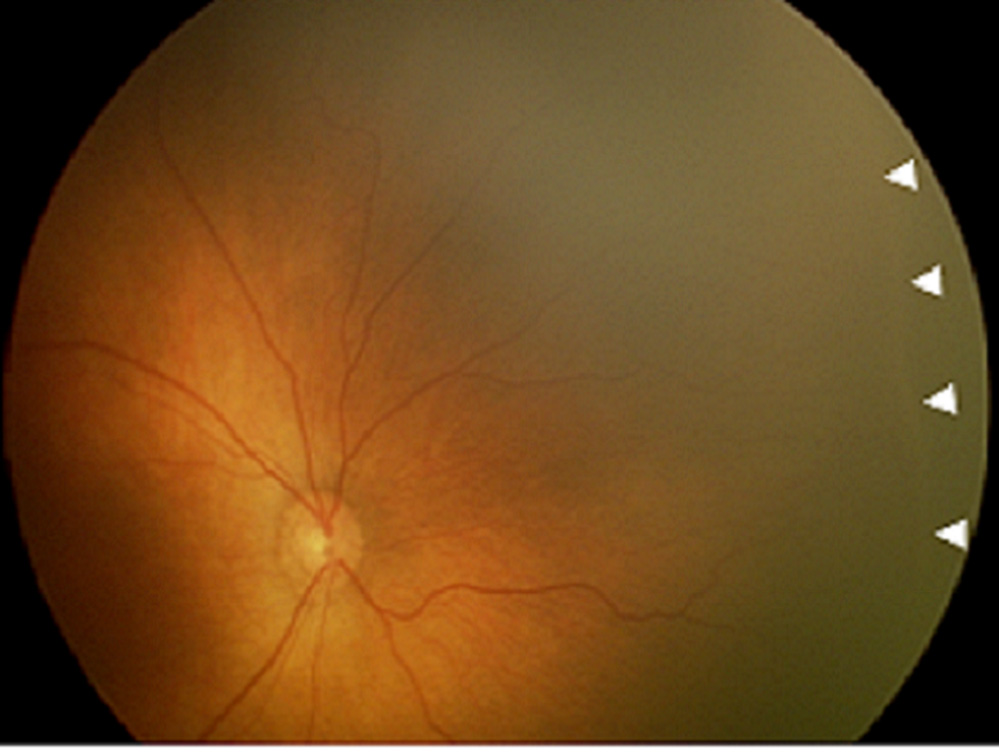

Figure 5 and Figure 6 display examples of diagnostic disagreements and agreements among single-image, multiple-image, and ophthalmoscopic examinations. Table 3 summarizes the sensitivity and specificity of each telemedicine grader for detection of disease with recommended follow-up intervals of <2 weeks and <1 week, compared to ophthalmoscopic examination at 31–33 weeks PMA; Table 4 provides the same information for exams performed at 35–37 weeks PMA There were no significant intra-grader differences in sensitivity and specificity for follow-up intervals between single-image and multiple-image exams, except for grader C who had lower specificity for detection of infants requiring follow-up in <1 week using multiple-image exam (p<0.001).

Figure 5. Example of diagnostic disagreement by single-image telemedicine examination for retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), compared to multiple-image and ophthalmoscopic examinations.

This was diagnosed as “no visible peripheral ROP” from single-image exam ([left] image) by all graders, as “mild ROP” from multiple-image exam ([left] and [right] images, plus temporal view) by all graders, and as “mild ROP” from ophthalmoscopic exam. Arrowheads show location of disease identified by graders.

Figure 6. Example of diagnostic agreement by single-image telemedicine examination for retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), compared to multiple-image and ophthalmoscopic examinations.

This was diagnosed as “type-2 or worse ROP” from single-image exam by all graders, as “treatment-requiring ROP” from multiple-image exam (this image, plus temporal and nasal views) by all graders, and as “type-2 prethreshold ROP” from ophthalmoscopic exam. Arrowheads show location of disease identified by graders.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of single-image and multiple-image telemedicine examinations at 31–33 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA) for detection of infants requiring retinopathy of prematurity follow-up in <2 weeks and <1 week.

| 31–33 weeks PMA | Grader A | Grader B | Grader C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Infants requiring follow-up in <2 weeks (n=18) | ||||||

| Single-image exam | 1.00 | 0.26* | 0.44* | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.83 |

| Multiple-image exam | 1.00 | 0.24* | 0.44* | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.48 |

| Infants requiring follow-up in <1 week (n=1) | ||||||

| Single-image exam | 1.00 | 0.89† | 1.00 | 0.98† | 1.00 | 0.95† |

| Multiple-image exam | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.68† |

Telemedicine examinations were performed by three retinal specialist graders. Sensitivity and specificity are calculated using a reference standard of ophthalmoscopic examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist.

For detection of required follow-up in <2 weeks: Grader A had lower specificity than graders B (p<0.001 for single-image exam, p<0.001 for multiple-image exam) and C (p<0.001 for single-image exam, p=0.007 for multiple-image exam). Grader B had lower sensitivity than graders A (p=0.002 for single-image exam, p=0.002 for multiple image exam) and C (p=0.008 for single-image exam, p=0.04 for multiple-image exam).

For detection of required follow-up in <1 week: Using single-image exam, grader B had higher specificity than grader A (p=0.03). Using multiple-image exam, grader C had lower specificity than graders A (p<0.001) and B (p<0.001). Using multiple-image exam, grader C had lower specificity than using single-image exam (p<0.001).

Table 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of single-image and multiple-image telemedicine examinations at 35–37 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA) for detection of infants requiring retinopathy of prematurity follow-up in <2 weeks and <1 week.

| 35–37 weeks PMA | Grader A | Grader B | Grader C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Infants requiring follow-up in <2 weeks (n=18) | ||||||

| Single-image exam | 1.00 | 0.38* | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.69 |

| Multiple-image exam | 1.00 | 0.36* | 0.83 | 0.93* | 0.94 | 0.57* |

| Infants requiring follow-up in <1 week (n=11) | ||||||

| Single-image exam | 1.00 | 0.84† | 0.73 | 0.96 | 0.82 | 0.98† |

| Multiple-image exam | 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.84† |

Telemedicine examinations were performed by three retinal specialist graders. Sensitivity and specificity are calculated using a reference standard of ophthalmoscopic examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist.

For detection of required follow-up in <2 weeks: Using single-image exam, grader A had lower specificity than graders B (p<0.001) and C (p<0.001). Using multiple-image exam, there were differences in specificity between all pairs of graders (p<0.001 for graders A vs. B, p=0.004 for graders A vs. C, p<0.001 for graders B vs. C).

For detection of required follow-up in <1 week: Using single-image exam, grader A had significantly lower specificity than graders B (p=0.03) and C (p=0.02). Using single-image exam, grader C had lower specificity than using multiple-image exam (p=0.02).

Sensitivity and specificity for single-image and multiple-image examinations for detection of visible peripheral ROP, type-2 or worse ROP, and plus disease, compared to ophthalmoscopic examination, were calculated. This is shown in Table 5 and Table 6 for exams performed at 31–33 and 35–37 weeks PMA, respectively. For detection of visible peripheral ROP, multiple-image exams by all three graders had significantly higher sensitivity than single-image exams at both 31–33 and 35–37 weeks PMA (p<0.001), but there were no significant differences in specificity. For detection of type-2 or worse ROP, multiple-image exams by two graders had significantly higher sensitivity than single-image exams at 35–37 weeks PMA (p<0.05). For detection of plus disease, there were no significant intra-grader differences in sensitivity or specificity between single-image and multiple-image exams.

Table 5.

Sensitivity and specificity of single-image and multiple-image telemedicine examinations at 31–33 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA) for detection of visible peripheral retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), plus disease, and type-2 or worse ROP.

| 31–33 weeks PMA | Grader A | Grader B | Grader C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Detection of visible peripheral ROP (n=50) | ||||||

| Single-image exam | 0.10* | 1.00 | 0.06* | 1.00 | 0.06* | 1.00 |

| Multiple-image exam | 0.70* | 0.94 | 0.92* | 0.94 | 0.86* | 0.99 |

| Detection of type-2 or worse ROP (n=7) | ||||||

| Single-image exam | 0.71 | 0.92† | 0.43 | 0.99† | 0.57 | 0.97 |

| Multiple-image exam | 0.71 | 0.96† | 0.71 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.93 |

| Detection of Plus disease (n=0) | ||||||

| Single-image exam | N/A§ | 0.95‡ | N/A§ | 0.96 | N/A§ | 1.00‡ |

| Multiple-image exam | N/A§ | 0.94‡ | N/A§ | 0.96 | N/A§ | 1.00‡ |

Telemedicine examinations were performed by three retinal specialist graders. Sensitivity and specificity are calculated using a reference standard of ophthalmoscopic examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist.

For detection of visible peripheral ROP: There were intra-grader differences in sensitivity between single-image and multiple-image exams by each grader (p<0.001), but no significant intra-grader differences in specificity. Using multiple-image exam, grader A had significantly lower sensitivity than grader B (p<0.001). Diagnoses of “unknown” from single-image exam were provided in 1 (0.8%) eyes by grader A, 3 (2.3%) eyes by grader B, and 31 (24.2%) eyes by grader C. Diagnoses of “unknown” from multiple-image exam were provided in 0 (0%) eyes by grader A, 24 (18.8%) eyes by grader B, and 52 (40.6%) eyes by grader C.

For detection of type-2 or worse ROP: There were no significant intra-grader differences in sensitivity between single-image and multiple-image exams by any grader, but grader A had a significant intra-grader difference in specificity between single-image and multiple-image exams (p=0.03). Using single-image exam, grader A had significantly lower specificity than grader B (p=0.008). Diagnoses of “unknown” from single-image exam were provided in 2 (1.6%) eyes by grader A, 0 (0.0%) eyes by grader B, and 0 (0.0%) eyes by grader C. Diagnoses of “unknown” from multiple-image exam were provided in 0 (0%) eyes by grader A, 24 (18.8%) eyes by grader B, and 52 (40.6%) eyes by grader C.

For detection of plus disease: There were no significant intra-grader differences in sensitivity or specificity between single-image and multiple-image exams. Using single-image exam, grader A had lower specificity than grader C (p=0.02). Using multiple-image exam, grader A had lower specificity than grader C (p=0.008). Diagnoses of “unknown” from single-image exam were provided in 2 (1.6%) eyes by grader A, 0 (0%) eyes by grader B, and 9 (7.0%) eyes by grader C. No diagnoses of “unknown” from multiple-image exam were provided by any grader.

N/A, not applicable. No reference standard ophthalmoscopic exams showed plus disease at 31–33 weeks PMA.

Table 6.

Sensitivity and specificity of single-image and multiple-image telemedicine examinations at 35–57 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA) for detection of visible peripheral retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), plus disease, and type-2 or worse ROP.

| 35–37 weeks PMA | Grader A | Grader B | Grader C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Detection of visible peripheral ROP (n=71) | ||||||

| Single-image exam | 0.14* | 0.96 | 0.14* | 0.96 | 0.02* | 0.98 |

| Multiple-image exam | 0.89* | 0.85 | 0.89* | 0.88 | 0.96* | 0.87 |

| Detection of type-2 or worse ROP (n=26) | ||||||

| Single-image exam | 1.00† | 0.87 | 0.69† | 0.98 | 0.77† | 1.00† |

| Multiple-image exam | 1.00 | 0.85 | 1.00† | 0.94 | 1.00† | 0.93† |

| Detection of Plus disease (n=12) | ||||||

| Single-image exam | 1.00 | 0.79‡ | 1.00 | 0.85‡ | 1.00 | 0.95‡ |

| Multiple-image exam | 1.00 | 0.77‡ | 1.00 | 0.89‡ | 1.00 | 0.94‡ |

Telemedicine examinations were performed by three retinal specialist graders. Sensitivity and specificity are calculated using a reference standard of ophthalmoscopic examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist.

For detection of visible peripheral ROP: There were intra-grader differences in sensitivity between single-image and multiple-image exams by each grader (p<0.001), but no significant intra-grader differences in specificity. Using single-image exam, grader C had lower sensitivity than graders A (p=0.008) and B (p=0.008). Diagnoses of “unknown” from single-image exam were provided in 1 (0.8%) eyes by grader A, 0 (0%) eyes by grader B, and 12 (10.0%) eyes by grader C. Diagnoses of “unknown” from multiple-image exam were provided in 0 (0%) eyes by grader A, 6 (5.0%) eyes by grader B, and 8 (6.7%) eyes by grader C.

For detection of type-2 or worse ROP: There were intra-grader differences in sensitivity between single-image and multiple-image exams by grader B (p=0.008) and C (p=0.03). There were intra-grader differences in specificity between single-image and multiple-image exams by grader C (p=0.03). Using single-image exam, grader A had higher sensitivity than grader B (p=0.008) and C (p=0.03). Using single-image exam, grader A had lower specificity than grader B (p=0.002) and C (p=0.004). No diagnoses of “unknown” from single-image exam were provided by any grader. Diagnoses of “unknown” from multiple-image exam were provided in 0 (0%) eyes by grader A, 6 (5.0%) eyes by grader B, and 8 (6.7%) eyes by grader C.

For detection of plus disease: There were no significant intra-grader differences in sensitivity or specificity between single-image and multiple-image exams. Using single-image exam, grader C had higher specificity than graders A (p<0.001) and B (p=0.003). Using multiple-image exam, grader A had lower specificity than graders B (p<0.001) and C (p<0.001). Diagnoses of “unknown” from single-image exam were provided in 1 (0.9%) eye by grader A, 0 (0%) eyes by grader B, and 0 (0%) eyes by grader C. No diagnoses of “unknown” from multiple-image exam were provided by any grader.

By multiple-image exam at 35–37 weeks PMA, no cases of type-2 ROP or plus disease were missed. However, by single-image exam, graders B and C had lower sensitivity for diagnosis of type-2 or worse ROP than for diagnosis of plus disease (Table 6). As shown in Table 3 through Table 6, there were significant inter-grader differences in sensitivity and specificity between several pairs of graders for recommended follow-up interval as well as diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to examine the results of telemedical ROP interpretation using single-image compared to multiple-image examinations. The key findings are that: (1) Most peripheral ROP disease was not visible in a single wide-angle posterior pole image. (2) Within each grader, the assignment of recommended follow-up intervals, as well as detection of plus disease, was very consistent between single-image and multiple-image exams. (3) For diagnosis of type-2 or worse ROP, single-image exams were less sensitive than multiple-image exams. (4) Among different graders, there were often significant differences in assignment of recommended follow-up interval, detection of plus disease, and detection of visible peripheral ROP.

An outcome metric in this study is “recommended follow-up interval,” with the rationale that this is a clinically-relevant measure for the result of telemedicine screening. Published policy statements suggest that follow-up exams for patients with mild or no ROP are usually done every 2 weeks, while more severe cases require shorter intervals to ensure timely detection of treatment-requiring disease.23,24 Individual physicians may have different preferences regarding follow-up intervals, which may explain some of the variance in recommendations among the three study examiners. By comparing performance of single-image vs. multiple-image telemedicine examinations within each grader, we control for individual grader preferences and compare these modalities more directly. Although the majority of peripheral ROP was not visible in single-image exams (Table 5 and Table 6), there were no significant differences in recommended follow-up intervals between single-image and multiple-image telemedicine interpretations performed by each grader (Table 3 and Table 4). As shown in Figure 3, when these intervals differed between exam modalities, the recommendations by both single-image and multiple-image telemedical examinations were more often shorter than those recommended by ophthalmoscopy.

There were also no significant differences in diagnosis of plus disease between single-image and multiple-image exams (Table 5 and Table 6). In fact, sensitivity for detection of plus disease by single-image examination was 100% at 35–37 weeks PMA for all 3 telemedicine graders, and no cases of treatment-requiring ROP were missed. This is not surprising, given that plus disease is defined based on a standard published photograph that includes only the central retina, and should in principle be diagnosed without regard to peripheral retinal findings.1,25,26 Studies have shown that automated computer-based image analysis using single posterior pole images may be an effective tool for diagnosing plus disease.27–31 Because presence of plus disease is a necessary feature of threshold disease and a sufficient feature for type-1 ROP, both of which have been shown to warrant treatment, single-image telemedical exam may have a role in ROP screening strategies.

With both single-image and multiple-image telemedical examinations, there were numerous statistically-significant inter-grader differences in assignment of recommended follow-up intervals and diagnosis of disease (Table 3 through Table 6). For example, grader A had significantly lower specificity than graders B and C for detection of required follow-up in <2 weeks, using both single-image and multiple-image examinations at 31–33 weeks and 35–37 weeks PMA. Similar inter-observer differences have been found in previous studies involving image-based diagnosis of plus disease, even among recognized ROP experts.27,30–32 It is important to note that, using outcome metrics such as presence of plus disease and recommended follow-up interval, there were no significant intra-grader differences between single-image and multiple-image exams. In comparison, there were several significant inter-grader differences among 3 experienced retinal specialists. From the perspective of screening to identify clinically-significant disease that requires shorter follow-up intervals or treatment, this suggests that the differences between single-image and multiple-image protocols are less important than calibration of individual graders.

In real-world telemedicine systems, the diagnostic cutoff triggering referral for full ophthalmoscopic examination may vary. In many settings, it may be reasonable to refer all infants felt by telemedical screening to have type-2 or worse ROP. This may decrease the likelihood of missing infants with true treatment-requiring ROP, at the cost of referring infants who will not require treatment. This is similar to what was described by Ells et al. as “referral-warranted ROP.”12 We note that sensitivity for diagnosing type-2 or worse ROP by two study graders was significantly lower by single-image exam than multiple-image exam (Table 5 and Table 6). This is presumably because retinal findings such as peripheral stage 3 ROP without plus disease might not be seen on a single wide-angle posterior pole photograph. Therefore, single-image exams are not adequate to completely substitute for ophthalmoscopy or multiple-image exams. But taken together, these study findings suggest that single-image exam appears comparable to multiple-image examination as a screening method for quickly identifying infants who require more detailed attention. This may be particularly relevant in areas where ophthalmoscopic or multiple-image telemedicine exams are impractical, or for infants who are at lower-risk for ROP because of larger birth weight and gestational age.

There are similar tradeoffs among diagnostic tests in other ophthalmic diseases, because of practical or logistical factors. The accepted standard for classifying diabetic retinopathy based on the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study involves seven images from each eye.17 However, studies have shown that approximately 50% of diabetic patients do not receive recommended annual dilated ophthalmoscopic examinations.33–35 In response to these pressures, alternative telemedical screening strategies involving only 1–3 images from each eye have been tested and implemented in primary care medical settings, often using non-mydriatic cameras.36,37 In diagnostic testing for glaucoma, 30-degree automated visual field tests provide more information than 24-degree tests. However, 24-degree fields have been shown to produce the same interpretation as 30-degree fields in 95–100% of cases, with shorter testing time and less variability.38 Furthermore, the Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm (SITA) was introduced as an alternative to full-threshold strategies for performing automated perimetry. Compared to full-threshold algorithms, SITA has been shown to require nearly 50% less time, while providing better inter-test variability and comparable test-retest threshold variability.39–41 Similar results were observed in SITA-based visual field tests performed on children, where patients’ shorter attention spans benefit from a shorter exam.42 Although there is a tradeoff of less information, these shorter exams are faster and therefore more practical for clinical application. For analogous reasons, single-image examination might benefit infants undergoing ROP screening, or the personnel who are responsible for capturing images.

Several additional limitations should be noted: (1) Dilated ophthalmoscopy was considered the reference standard. Although this has been the design of nearly all ROP telemedicine studies,7–14,16 image-based exams may not be inherently less “correct” than ophthalmoscopy. In fact, we have previously demonstrated that there were numerous disagreements between ophthalmoscopic and image-based diagnoses performed by the same physician, and that telemedicine may actually be more accurate in some cases.15 (2) All images were obtained by a trained NICU nurse at a large academic center. Further research may be required to examine whether these findings are generalizable to different nurses. This is important because a real-world ROP telemedicine system would place heavy responsibility upon imaging personnel for recognizing and capturing clinically-relevant findings, analogous to the role of ultrasonographers and technicians in radiology. It is possible that multiple images could allow for better grading if imaging personnel are less adept at capturing clinically-relevant findings on a single image. (3) During data analysis, “unknown” responses were excluded to avoid penalizing graders for discomfort with providing a diagnosis. This biases toward better telemedicine performance, because ungradable images in real-world systems would require either repeat photography or referral for ophthalmoscopy. The number of “unknown” responses for severe diagnoses using single-image and multiple-image exams (presence of type-2 or worse ROP, presence of plus disease) was low at 35–37 weeks PMA, but not for all graders at 31–33 weeks (Table 5 and Table 6). (4) This study was not designed to identify the reasons for “unknown” responses. For example, it is not clear why there were fewer “unknown” responses for single-image than multiple-image telemedicine exams (Table 1). Additional studies to examine the cognitive processes underlying diagnosis may provide further insights. (5) The number of infants with severe disease was small, particularly at 31–33 weeks PMA (Table 3 through Table 6). This may limit the generalizability of results. (6) This study found that imaging examinations are associated with shorter follow-up intervals than ophthalmoscopy. The cost-benefit implications of more frequent examinations may warrant further study, particularly given that this may result in increased stress for infants.21–22,43 (7) Multiple-image exams in this study were reviewed by graders immediately after single-image exams. This was done to decrease bias from imperfect intra-grader reliability14–16 and to isolate diagnostic differences due to single-image vs. multiple-image modalities. To support this design, our telemedicine system prohibited graders from returning to the single-image exam page while interpreting multiple-image exams. To decrease likelihood that viewing an abbreviated exam prior to the full image set would alter grader judgments, single-image exams were a complete subset of multiple-image exams. However, this study design may introduce bias if graders developed preconceived notions after viewing single-image exams. Future research may provide additional insights.

Overall, this study shows that single-image telemedicine exams using a wide-angle retinal camera perform comparably to multiple-image exams for determining recommended follow-up intervals, as well as for detecting plus disease. Because of lower sensitivity for detecting type-2 or worse ROP, single-image exams cannot fully substitute for multiple-image exams or indirect ophthalmoscopy. These findings may have implications for the development of rapid ROP screening protocols, particularly in areas with limited access to ophthalmic care. Future work in standardizing the image capture and reading processes will be beneficial.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DISCLOSURES

A. Funding and Support: Supported by a Career Development Award from Research to Prevent Blindness (MFC), and by grant EY13972 from the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health (MFC).

B. Financial Disclosures: MFC is an unpaid member of the Scientific Advisory Board for Clarity Medical Systems (Pleasanton, CA). The authors have no commercial, proprietary, or financial interest in any of the products or companies described in this article.

C. Contributions of Authors: Conception and design (AL, SK, OC, JTF, JS, MFC); Analysis and interpretation (AL, SK, LW, YED, TCL, DJW, AMB, SAK, MFC); Writing the article (AL, SK, MFC); Critical revision of the article (SAK, YED, LW, TCL, DJW, AMB, OC, JS, JTF); Final approval of the article (AL, SK, LW, SAK, YED, TCL, DJW, AMB, OC, JS, JTF, MFC); Data collection (SAK, LW, TCL, DJW, AMB, OC, MFC); Provision of materials, patients, or resources (SAK, TCL, DJW, AMB, OC, MFC); Statistical expertise (YED, SK); Obtaining funding (MFC); Literature search (AL, SK, MFC); Administrative, technical, or logistic support (OC, LW, TCL, DJW, AMB, JS, JTF, MFC).

D. Statement about Conformity with Author Information: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Columbia University Medical Center, and was conducted in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Written informed consent was provided by parents of all study subjects before participation.

E. Other Acknowledgements: None.

Biographies

Alexandra Lajoie is a medical student at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Class of 2010. Alexandra grew up in the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains, and earned an AB with honors in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and a Certificate in French Language and Culture from Princeton University in 2006. She is interested in a broad range of topics in ophthalmology, with a current special interest in pediatric ophthalmology.

Michael F. Chiang is Irving Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology and Biomedical Informatics at Columbia University. His research involves implementation and evaluation of telemedicine and electronic health record systems. Dr. Chiang received a B.S. in Electrical Engineering and Biology from Stanford University, an M.D. from Harvard Medical School and Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, and an M.A. in Biomedical Informatics from Columbia University. He completed residency and pediatric ophthalmology fellowship training at the Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Multicenter trial of cryotherapy for retinopathy of prematurity: preliminary results. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:471–479. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060130517027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Revised indications for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity: results of the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1684–1694. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.12.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert C, Foster A. Childhood blindness in the context of VISION 2020: the right to sight. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:227–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert C, Fielder A, Gordillo L, et al. Characteristics of infants with severe retinopathy of prematurity in countries with low, moderate, and high levels of development: Implications for screening programs. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e518–e525. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Ophthalmology. [Accessed February 29, 2008];Ophthalmologists warn of shortage in specialists who treat premature babies with blinding eye condition. Available at http://www.aao.org/newsroom/release/20060713.cfm.

- 6.Bashshur RL, Reardon TG, Shannon GW. Telemedicine: A new health care delivery system. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:613–637. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yen KG, Hess D, Burke B, et al. The optimum time to employ telephotoscreening to detect retinopathy of prematurity. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:145–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu C, Petersen RA, Vanderveen DK. Retcam imaging for retinopathy of prematurity screening. J AAPOS. 2006;10:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah P, Narendran V, Saravanan V, Raghuram A, Chattopadhyay A, Kashyap M. Screening for retinopathy of prematurity--a comparison between binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy and RetCam 120. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2006;54(1):35–38. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.21612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz SD, Harrison SA, Ferrone PJ, Trese MT. Telemedical evaluation and management of retinopathy of prematurity using a fiberoptic digital fundus camera. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:25–28. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth DB, Morales D, Feuer WJ, Hess D, Johnson RA, Flynn JT. Screening for retinopathy of prematurity employing the RetCam-120: sensitivity and specificity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:268–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ells AL, Holmes JM, Astle WF, et al. Telemedicine approach to screening for severe retinopathy of prematurity: a pilot study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:2113–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00831-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang MF, Starren JB, Du YE, et al. Remote image based retinopathy of prematurity diagnosis: A receiver operating characteristic analysis of accuracy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1292–1296. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.091900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiang MF, Keenan JD, Starren JB, et al. Accuracy and reliability of remote retinopathy of prematurity diagnosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:322–327. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.3.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott KE, Kim DY, Wang L, et al. Telemedical retinopathy of prematurity diagnosis: intra-physician agreement between ophthalmoscopic and image-based examinations. Ophthalmology. Forthcoming. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiang MF, Wang L, Busuioc M, et al. Telemedical diagnosis of retinopathy of prematurity: accuracy, reliability, and image quality. Arch Ophtahlmol. 2007;125:1531–1538. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.11.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs--an extension of the modified Airlie House classification. ETDRS report number 10. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:786–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders RA, Hutchinson AK. The future of screening for retinopathy of prematurity. J AAPOS. 2002;6:61–63. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2002.122963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders RA, Donahue ML, Berland JE, et al. Non-ophthalmologist screening for retinopathy of prematurity. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:130–134. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.2.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert C, Rahi J, Eckstein M, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity in middle-income countries. Lancet. 1997;350:12–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukherjee AN, Watts P, Al-Madfai H, Manoj B, Roberts D. Impact of retinopathy of prematurity screening examination on cardiorespiratory indices: a comparison of indirect ophthalmoscopy and retcam imaging. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1547–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laws DE, Morton C, Weindling M, Clark D. Systemic effects of screening for retinopathy of prematurity. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:425–428. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.5.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Section on Ophthalmology AAP, AAO, AAPOS. Screening examination of premature infants for retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatrics. 2001;108:809–811. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Section on Ophthalmology AAP, AAO, AAPOS. Screening examination of premature infants for retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatrics. 2006;117:572–576. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.International committee for the classification of retinopathy of prematurity. The international classification of retinopathy of prematurity revisited. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:991–999. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.7.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Committee for the classification of retinopathy of prematurity. An international classification of retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1130–1134. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030908011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiang MF, Gelman R, Jiang L, Martinez-Perez ME, Du YE, Flynn JT. Plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity: an analysis of diagnostic performance. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2007;105:73–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace DK, Jomier J, Aylward WR, Landers MB. Computer-automated quantification of plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity. J AAPOS. 2003;7:126–130. doi: 10.1016/mpa.2003.S1091853102000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gelman R, Martinez-Perez ME, Vanderveen DK, et al. Diagnosis of plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity using Retinal Image multiScale Analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4734–4738. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koreen S, Gelman R, Martinez-Perez ME, et al. Evaluation of a computer-based system for plus disease diagnosis in retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:e59–e67. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelman R, Jiang L, Du YE, Martinez-Perez ME, Flynn JT, Chiang MF. Plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity: pilot study of computer-based and expert diagnosis. J AAPOS. 2007;11:532–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiang MF, Jiang L, Gelman R, et al. Interexpert agreement of plus disease diagnosis in retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:875–880. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.7.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoenfeld ER, Greene JM, Wu SY, Leske MC. Patterns of adherence to diabetes vision care guidelines: Baseline findings from the Diabetic Retinopathy Awareness Program. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:563–571. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brechner RJ, Cowie CC, Howie LJ, Herman WH, Will JC, Harris MI. Ophthalmic examination among adults with diagnosed diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 1993;270:1714–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukamel DB, Bresnick GH, Wang Q, Dickey CF. Barriers to compliance with screening guidelines for diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1999;6:61–72. doi: 10.1076/opep.6.1.61.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams GA, Scott IU, Haller JA, Maguire AM, Marcus D, McDonald HR. Single-field fundus photography for diabetic retinopathy screening: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1055–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin DY, Blumenkranz MS, Brothers RJ, Grosvenor DM. The sensitivity and specificity of single-field nonmydriatic monochromatic digital fundus photography with remote image interpretation for diabetic retinopathy screening: a comparison with ophthalmoscopy and standardized mydriatic color photography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:204–213. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khoury JM, Donahue SP, Lavin PJ, Tsai JC. Comparison of 24-2 and 30-2 perimetry in glaucomatous and nonglaucomatous optic neuropathies. J Neuroophthalmol. 1999;19:100–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bengtsson B, Heijl A. Evaluation of a new perimetric threshold strategy, SITA, in patients with manifest and suspect glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 1998;76:268–272. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bengtsson B, Heijl A, Olsson J. Evaluation of a new threshold visual field strategy, SITA, in normal subjects. Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 1998;76:165–169. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bengtsson B, Heijl A. Inter-subject variability and normal limits of the SITA Standard, SITA Fast, and the Humphrey Full Threshold computerized perimetry strategies, SITA STATPAC. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77:125–129. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donahue SP, Porter A. SITA visual field testing in children. J AAPOS. 2001;5:114–117. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2001.113840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jackson KM, Scott KE, Zivin JG, et al. Cost-utility analysis of telemedicine and ophthalmoscopy for retinopathy of prematurity management. Arch Ophthalmol. Forthcoming. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.4.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]