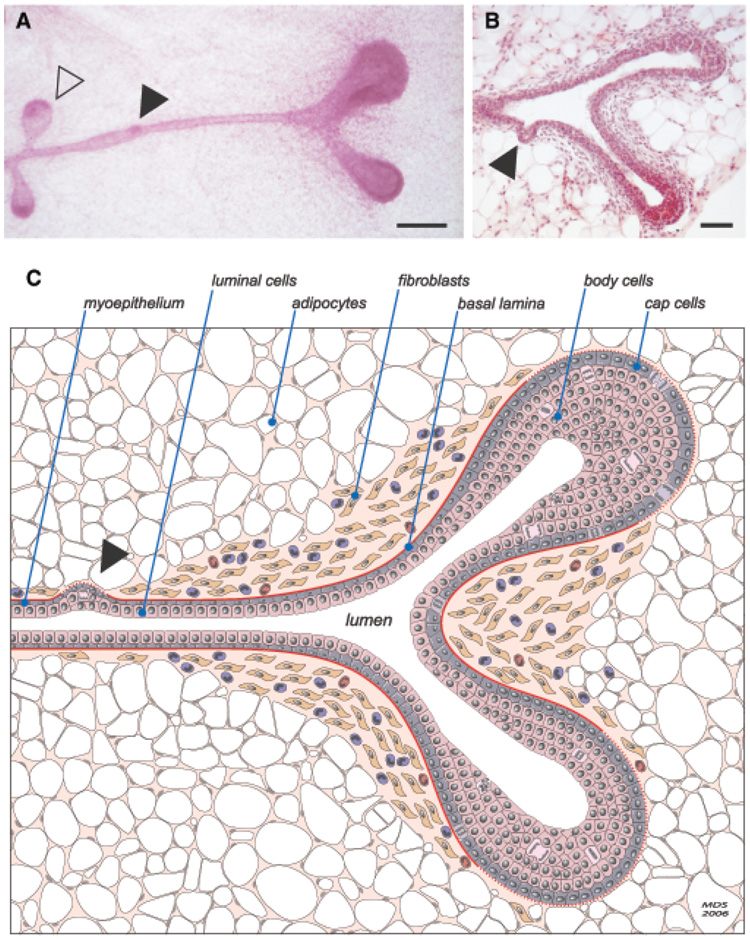

Fig. 1.

Murine terminal end bud (TEB) and duct morphology. (A) High-magnification carmine alum-stained whole mount of a TEB that has recently bifurcated to form two new primary ducts. Two new secondary side-branches are also present along the trailing duct (open arrowhead), as is an area of increased cellularity that may represent a nascent lateral bud (closed arrowhead). Increased stromal cellularity is apparent around the bifurcating TEB. Scale bar: 200 µm. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained section of a bifurcating TEB with an early lateral side-branch (closed arrowhead). Scale bar: 100 µm. (Image courtesy of A.J. Ewald, UCSF) (C) Schematic diagram depicting the major features of a bifurcating TEB. Notable features include the considerable proliferative activity (mitoses) within the TEBs, the single layer of TEB cap cells and multilayered pre-luminal body cells, the characteristic presence of a fibroblast-and collagen-rich stromal collar surrounding the neck of the bifurcating TEB, and its conspicuous absence beyond the invading distal cap of each new TEB. An increased number of macrophages and eosinophils is also shown. Although there is no evidence that normal ductal cells ever cross the basal lamina, thinning of the basement membrane (dashed lines) at the leading edge of the invading ducts may reflect partial enzymatic degradation and/or incomplete de novo synthesis of the basal lamina.