Abstract

We report a unique property of nanocapillaries for chromatographic separations of ionic species. Due to the electric double layer overlap, ions are unevenly distributed inside a nanochannel, with counterions enriched near the wall and co-ions concentrated in the middle of the channel. As a pressure-driven flow is induced, the co-ions will move faster than the counterions. This differential transport results in a chromatographic separation. In this work, we introduce the fundamental mechanism of this separation technology and demonstrate its application for DNA separations. An outstanding feature of this technique is that each separation consumes less than 1 pL sample and generates less than 0.1 nL waste. We also apply this technique for separations of DNA molecules, and efficiencies of more than 100 000 plates per meter are obtained.

Keywords: Nanochromatography, Nanocapillary, Nanochannel, Chromatography, DNA Separation

1. INTRODUCTION

Current micro- and nano-fabrication technologies enable reliable production of fluidic channels in low micrometer and nanometer scales [1–12]. Electrokinetic transport of liquid and ions in these nanometer-scale channels (nanochannels) has exhibited a series of distinctive effects [1–3], and applications of these effects are being explored for practical uses [4,5,13]. Normally, DNA cannot be separated by capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE), because the electrophoretic mobilities of all DNA molecules are virtually identical in gel-free solutions [14]. Peterson et al. [15] showed that separations of DNA by CZE are possible as long as the channel depth (or capillary diameter) is sufficiently small (e.g. tens of nanometers). Pennathur and Santiago [13,16] studied the fundamental mechanisms of similar separations in nanochannels, and termed this separation technique electrokinetic separations by ion valences (EKSIV). Han et al. [17–21] also demonstrated separations of long DNA molecules in nanochannels containing entropic traps. All these separations were performed under the influence of an external longitudinal electric field.

Interestingly, ionic species can also be separated in a nanocapillary under pressure-driven flow conditions. Figure 1 illustrates the basic mechanism of this separation. Owing to the electric double layer (EDL) overlap, ions are unevenly distributed inside a nanochannel [1,4,22–24]. For example, inside a silica capillary whose surface is negatively charged, anions are concentrated in the middle of the channel (see Figure 1a), while cations are enriched near the channel wall (see Figure 1b) due to the electrostatic repulsive/attractive forces between the ions and the charged surface. When a pressure-driven (Poisseuille) flow is induced (see Figure 1c and Figure 1d), the anions will move faster than the cations. A chromatographic separation is thus produced (compare the relative positions of the anion in Figure 1e and the cation in Figure 1f). Since this separation mechanism has not been reported before and it dominates the separations of ions in nanocapillaries, we tentatively call this type of separations nanocapillary chromatography (NC). In this work, the nanocapillary refers to a capillary whose radius is in the sub-micrometer domain.

Figure 1. A schematic presentation of NC separation in a nanocapillary under pressure-driven conditions.

From the perspective of field-flow fractionation (FFF) [25], NC is similar to electrical FFF (EFFF). In EFFF, an external electric field is applied to force ionic species to reside near a wall of a channel in which a pressure-driven flow is effected [26]. Species with the highest electric charge are driven most forcefully toward the channel surface, and form the most compact layers. These species, confined in the low-flow region, will move more slowly than the low-charge species, and thus have longer retention times. Electric fields have the advantage of being exceedingly powerful, which means they can induce the migration of virtually all (large or small) charged species toward the accumulation wall. The implementation of EFFF, however, has been difficult because of the need to avoid the generation of electrolysis products in the channel [27]. NC overcomes this problem, since the electric field comes from the zeta potential at the capillary wall, and an electric field is created without electrolysis.

Because co-ions are somehow “excluded” from the wall (see Figure 1a) and counterions are “excluded” from the center of the capillary, NC can be considered to be a special format of ion-exclusion chromatography [28]. The solutions in these ion-exclusion regions are equivalent to the occluded liquids in ion-exclusion chromatography. The quotation marks indicate that ions are not absolutely excluded from these regions. [Note: Novic and Haddad [29] have recently suggested that ions diffuse to the occluded liquids as well in ion-exclusion chromatography.] Since the volume of such equivalent occluded liquid increases with the net charge on an analyte ion, analytes can be separated according to the volumes of their equivalent occluded liquids. However, there are some unique features for these separations. (1) All occluded liquids are part of the mobile phase; (2) the occluded liquids of co-ions move slower, and those of counterions move faster than the associated mobile phase; and (3) as a consequence of the above feature, all co-ions will have negative retentions (or the retention times of all co-ions are shorter than that of the associated eluent).

It should be pointed out that, while we were working on this project, Xuan and Li [30] developed a model that predicts differential retentions of ions under pressure-driven conditions, but no experimental data were shown. In this paper, we introduce the fundamental separation mechanism, and experimentally demonstrate the feasibility of NC for ion separations. We test the effects of key experimental parameters such as buffer concentration and separation pressure on separation efficiency and resolution, and demonstrate the application of NC for separations of DNA molecules.

2. THEORY

In a narrow capillary with a negatively charged surface, the potential function has been derived [31], and has the following form,

| (1) |

where I0 is the zero-order modified Bessel function of the first kind, κ is the reciprocal of the double-layer thickness (at 25 °C, [23], where I is the ionic strength of the background electrolyte solution), R is the radius of the capillary, r is the independent variable representing the distance to the center of the capillary, and ϕ0 is the zeta potential (ζ). Once a capillary and a background electrolyte solution are selected, κR is known, and ϕ can be calculated using Eq. 1.

Referring to Figure 1a and Figure 1b, when a plug of ionic sample is introduced into the capillary, the concentration profile of an ion inside the capillary can be calculated using Boltzmann equation,

| (2) |

where C0 is the concentration of ion i at ϕ= 0, zi is the number of unit charge on the ion, e is the charge of the electron, k is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature.

Under a Poisseuille flow condition, the migration of an ion inside a nano-scale capillary can be evaluated from the ion distribution and flow profile. The velocity profile of a Poisseuille flow is expressed as [32],

| (3) |

where υmax is the maximum velocity in a Poisseuille flow and it is located in the center (r = 0) of the capillary. The average flow velocity is,

| (4) |

Since ions are unevenly distributed across the radius of the capillary, the average velocity of ion i is calculated by the following equation,

| (5) |

We now define the NC mobility of ion i as

| (6) |

As long as the potential function and flow profiles are known, NC mobilities can be calculated based on Eq. 2, Eq. 3 and Eq. 6. Figure 2 presents a typical relationship between the NC mobility and the z value of an ion. For simplicity of the presentation, only the data points from z = −10 to z = 10 are displayed. From this relationship, we draw three conclusions that are basic features of NC.

Figure 2. NC mobility of an ion as a function of its charge.

To calculate the data points in this figure, we assumed a capillary radius to be 5λ (where λ is the Derbye thickness of the EDL, λ = κ−1), a zeta potential to be 50 mV, and a velocity profile of a Poisseuille flow. The mobility of a neutral compound (or the bulk solution) was set as 1.

Feature 1

Co-ions move faster than neutral species, and neutral compounds migrate faster than counterions. In addition, a higher charged co-ion moves faster than a lower charged co-ion, while a higher charged counterion moves slower than a lower charged counterion. Here, co-ions and counterions are relative to the charge on the inner surface of the nanocapillary.

Feature 2

The unit-charge resolution (ΔR/Δz) decreases with the absolute value of z. For example, separating X−1 and X−2 is easier than separating X−10 and X−11.

Feature 3

A condition of ζ (zeta potential) ≠ 0 is required for NC separations to occur. If ζ = 0, all substances will be uniformly distributed inside a nanochannel, and all species will have the same unity NC mobility.

3. EXPERIMENTAL

3.1 Reagents and materials

2′,7′-Bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). A 100-base-pair (bp) DNA ladder was obtained from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ, USA), and a 1-kilobase-pair (kbp) DNA ladder was purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). TOTO-1 was obtained from Molecular Probes. Fluorescein and hydroxypropylcellulose (HPC, MW 80 000) were obtained from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI, USA). Rhodamine B, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate (EDTA), tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris), and other common reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fisher, PA, USA). Fused silica capillaries were obtained from Polymicro Technologies (Phoenix, AZ, USA). All solutions were prepared with ultra-pure water purified by a NANO pure infinity ultrapure water system (Barnstead, Newton, WA, USA), filtrated via 0.2 µm Whatman (Maidstone, UK) membrane filter, and degassed before use.

3.2 Preparation of HPC-coated capillary

The capillary was washed with 1 M NaOH for ~1 h, rinsed with deionized (DI) water for ~30 min, and dried with helium. 1% HPC aqueous solution was flushed through the capillary, and the solution inside the capillary was blown out using a 60 psi (1 psi = 6894.76 Pa) nitrogen. While the nitrogen was blowing, the capillary was baked at 140 °C for ~20 min. The steps of HPC-flushing, nitrogen-blowing and baking were repeated 5~6 times to complete the coating process. This capillary was dry-stored, if not immediately used.

3.3 Preparation of fluorescent-dye-intercalated DNA samples

The double-stranded (ds) DNA ladders were mixed with TOTO-1 at a dye-to-base pair ratio of ~1:10 in 1× TE (10.0 mM Tris-HCl, 1.0 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) buffer. The final total DNA concentrations were 50 ng/µL for the 1-kbp ladder and 60 ng/µL for the 100-bp ladder. The samples were freshly prepared right before use.

3.4 Apparatus

Figure 3 presents the experimental setup utilized to perform NC separations. The sampling end of the nanocapillary was inserted into a vial through a septum. A pressure-regulated helium gas was introduced to the headspace to drive the solution in the vial into the capillary. At an appropriate location on the capillary the polyimide coating was removed, forming a detection window. The detection end of the capillary was affixed to a capillary holder which was attached to an x-y-z translation stage to align the detection window with the optical system to maximize the fluorescent output. The fluorescence measurement was carried out on a confocal laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) detector. The LIF detector was basically a duplicate of the system described previously [33]. Briefly, a 488 nm beam from an argon ion laser (LaserPhysics, Salt Lake City, UT) was reflected by a dichroic mirror (Q505LP, Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT) and focused onto the nanocapillary through an objective lens (20x and 0.5 NA, Rolyn Optics, Covina, CA, USA). Fluorescence from the nanocapillary was collimated by the same objective lens, and collected by a photosensor module (H5784-01, Hamamatsu, Japan) after passing through the dichroic mirror, an interference band-pass filter (532 nm, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and a 2-mm pinhole. The magnification of the photosensor was modulated by an external d.c. power supply (Model C7169, Hamamatsu) to 0.7 V (equivalent to ~700 V on the photomultiplier tube of the photosensor). The output of the photosensor module was measured using a NI multifunctional card DAQCard-6062E (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). The data were acquired and treated with program written in-laboratory with Labview (National Instruments).

Figure 3. A schematic diagram of the experimental setup.

3.5 Alignment of the detection window with the optical system

Referring to Figure 3, a fluorescein solution (1~2 µM) was loaded into the solution vial, and a regulated pressure (~60 psi) was introduced into the headspace. While the solution was flowing through the capillary at a constant flow rate (to avoid fluorescence intensity decay caused by photo-bleaching), the position of the detection window was adjusted via the translation stage, and the fluorescence signal was monitored. Once the maximum signal output was reached, the x, y and z positions of the translation stage were locked, and the detection window was aligned with the optical system.

3.6 Operation of NC separation

Before sample injection (especially after capillary alignment), the capillary was thoroughly cleaned with an eluent solution until the fluorescence signal went to background level. Referring to Figure 3, a sample solution was loaded into the solution vial, and the three-way valve was set at vent. The sampling end of the capillary was then inserted into the sample solution in the vial with the help of a stainless needle (to pierce the septum). The three-way valve was switched to the position as shown in Figure 3 so that a pressure-regulated helium gas was introduced into the headspace of the vial, and the sample was pressurized into the capillary. A timer was used to control the volume of sample being injected. After the sample injection, the capillary was pulled out quickly, and transferred to a vial containing an eluent solution. As the eluent was pressurized through the capillary using the same approach as for sample injection, analytes were pushed across the detection window, and an NC separation was accomplished.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this paper, we consider an NC separation to be resulted solely from the uneven distributions of ions in the axial direction of a nanocapillary combined with a pressure-driven flow in the capillary. In any practical NC separation, many other mechanisms may contribute to the separations. For example, since counterions are enriched near the oppositely charged wall, ion-exchange interactions [34] will inevitably occur. In many cases, this mechanism [35–37] may play a major role in counterion separations. Mechanisms of hydrophobic-hydrophobic interaction, hydrodynamic separation [38,39] and radial migration [40] may also be involved when analytes change. In reality, a “pure” NC separation is hard to find, but the NC separation principle will dominate the analyte retentions when small co-ions are separated.

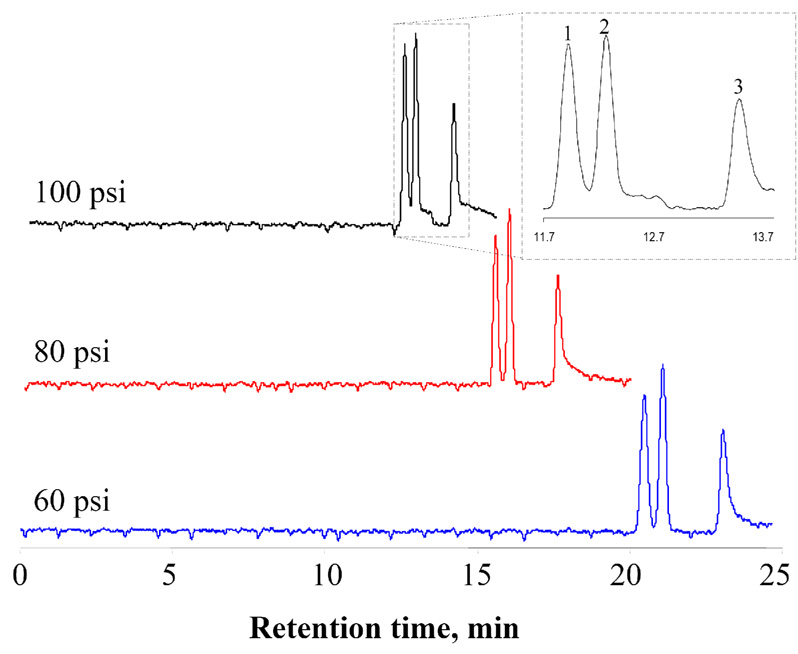

To demonstrate the feasibility of NC, we performed a series of NC separations using a 44-cm-long (39-cm effective length) and 800-nm-radius fused silica capillary as the separation column, a mixture of 0.5 µM rhodamine B (neutral), 0.1 µM fluorescein (−2 charged) and 0.2 µM 2′,7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF, −4 charged) in 100 µM sodium tetraborate as the sample, and a 100-µM sodium tetraborate solution as the eluent. Figure 4 presents three chromatograms that were obtained under different separation pressures. Referring to the top chromatogram, the numbers of theoretical plates were 38 000, 45 000 and 31 000 for peaks 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The plate numbers (N) were calculated based on

| (7) |

where t is the migration time and Δt1/2 is peak width at half-maximum. Since the effective separation length was 39 cm, the plate height was around or less than 10 µm, corresponding to efficiencies of ~100 000 plates per meter. These efficiencies are comparable to those from CZE. Presumably, the high efficiencies are obtained mainly due to the rapidness of ion re-distribution (to satisfy Boltzmann equation [23,24]) as the analyte zones move forward. If we assume a zeta potential value of −100 mV, an axial field strength of ~1.3 kV/cm will be present. An anion can be electrophoretically driven from the wall to the center of the capillary in less than 1 microsecond. It takes ~1 millisecond for the anion to diffuse back to the wall. Under the experimental conditions (low pressure and low flow rate) as legended in Figure 4, ion redistributions equilibrated virtually instantaneously. Consequently, peak tailings and frontings were avoided, and high separation efficiencies were achieved.

Figure 4. Comparison of three separation traces obtained under different separation pressures.

The separations were carried out using a 44-cm-long (39-cm effective length) and 800-nm-radius fused silica capillary under the indicated pressures. Sample injection condition: 80 psi for 10 seconds; Eluent composition: 100 µM borax. Peak identification: 1 – BCECF (−4 charged), 2 – fluorescein (−2 charged) and 3 – rhodamine B (neutral).

From these results presented in Figure 4, resolutions [R=2x(tb−ta)/(wa+wb), where ta and tb are the migration times and wa+wb are the peakwidths of compounds a and b] were calculated, as well. The resolution between rhodamine B and fluorescein was ~4.0, and that between fluorescein and BCECF was ~1.2. Because Δz = 2 in both cases, these results are in agreement with NC Feature 2.

NC separations of rhodamine 6G (a cationic fluorescent dye) were also performed. However, its retention times were long (~5-fold of those of rhodamine B), and the peaks were severely tailed. This is an indication that the analyte was strongly retained at the wall. [Apparently, counterion adsorptions might be an inherent issue for NC. In this experiment, we focused on mainly co-ion separations.] Nevertheless, the results of this separation and those in Figure 4 are consistent with NC Feature 1.

Figure 5 presents the effect of capillary size on resolution. The resolution decreased dramatically as the capillary radius increased from 0.5 µm to 3 µm. These results are comprehensible because ions were more evenly distributed in larger capillaries than that in smaller capillaries. Referring back to Figure 1a and Figure 1b, if ions are evenly distributed in the capillary, NC resolutions will disappear. Due to the unavailability of narrow capillaries, we did not obtain any data from capillaries with radii of smaller than 500 nm.

Figure 5. Effect of capillary size on resolution.

All separation capillaries had the same length (25.7 cm total and 21.7 cm effective) but different radii, (A) 500 nm, (B) 800 nm and (C) 3000 nm, respectively. Sample injection conditions: (A) 10 s at 100 psi, (B) 5 s at 60 psi and (C) 4 s at 50 psi. The separation pressures were identical (100 psi) for all cases.

One may argue that the resolution reduction in the above tests was caused by the diminished residence times in the larger capillaries. To compensate this, we dropped the separation pressure to 45 psi for the 800-nm-radius capillary and 25 psi for the 3-µm-radius capillary. Under these pressures, the retention times of the first peaks for all three separations became comparable. Although the resolutions did improve slightly (data not shown) under these conditions, the separation qualities were not nearly as good as that of trace A in Figure 5. However, these results were still disputable because the separation pressures were slashed. To maintain the same overall pressure and comparable retention times, we increased the total capillary length to 37.3 cm for the 800-nm-radius capillary and 58.0 cm for the 3-µm-radius capillary. Figure 6 presents the separation results. The resolutions from the 500-nm-radius capillary were still the best. We expect that the resolutions will keep improving with the decrease of capillary radius. Unfortunately, narrower capillaries are not commercially available at the time being owing to the manufacturing challenges.

Figure 6. Effect of capillary size on resolution after compensations of retention times.

The 500-nm-radius capillary had a total length of 25.7 cm and an effective length of 21.7 cm for trace a, the 800-nm-radius capillary had a total length of 37.3 cm and an effective length of 33.3 cm for trace b, and the 3000-nm-radius capillary had a total length of 58.0 cm and an effective length of 54.0 cm for trace c. Sample injection conditions were 10 s at 100 psi and the separation pressure was 100 psi for all three separations.

The above tests also indicated that the resolution increased with the reduction of the separation pressure. A systematic investigation (see the data in Figure 7) showed that there was an optimum pressure for highest resolutions. From the same chromatograms, a van Deemter plot (Figure 8) exhibited a typical trend. It appears to us that the longitudinal diffusion dominated the band broadening at low flow velocity (<0.2 mm/s), and other dispersion factors dominated the band broadening at high flow velocity (>0.4 mm/s). [The flow velocity (u) had a very good linear relationship with the applied pressure (Δp), u (mm/s) = 0.0046Δp (psi)]. We suspect that a separation mechanism transition might have occurred. More detailed investigation is needed to confirm this suspension. Based on the results presented in Figure 7 and Figure 8, the optimum separation pressure was around 45–90 psi. However, this optimum pressure will vary, depending on other experimental conditions such as the capillary size and the nature of the analytes.

Figure 7. Effect of separation pressure on resolution.

The experiment was performed using an 800-nm-radius capillary with a total length of 25.7 cm and an effective length of 21.7 cm. All other conditions were the same as those for the top chromatogram of Figure 4.

Figure 8. Effect of separation pressure on plate height (van Deemter plot).

The plate height data were calculated from the BCECF peaks in the same separation traces as for Figure 7.

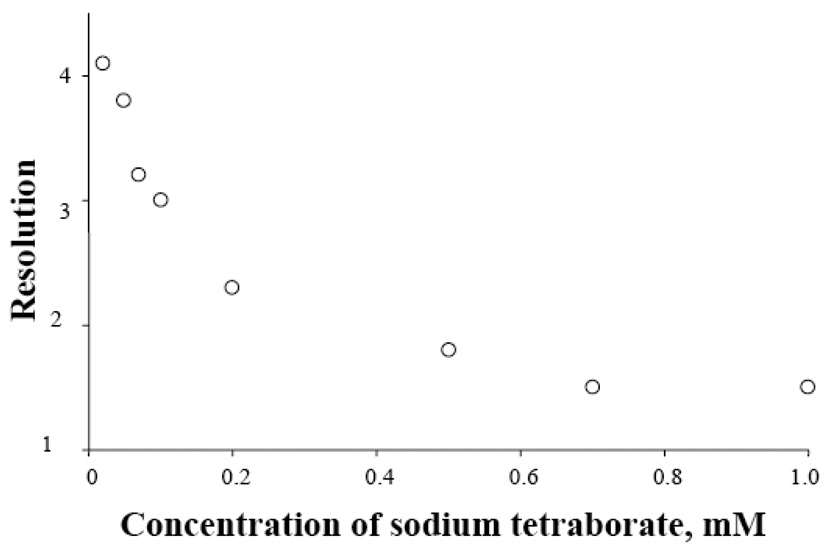

Figure 9 exhibits the resolution as a function of sodium tetraborate (eluent) concentration. The resolution reduced considerable with the increase of [Na2B4O7]. The reason was that, presumably, enhanced background electrolyte concentration decreased the thickness of EDL. In this experiment, we could not decrease [Na2B4O7] indefinitely since Na2B4O7 was the background electrolyte as well as the pH buffer reagent. At low [Na2B4O7], the experimental results became irreproducible

Figure 9. Effect of sodium tetraborate concentration on resolution.

The resolution was calculated from peaks 2 and 3. Except for the sodium tetraborate concentration, all other conditions were the same as those for the top chromatogram of Figure 4.

Based on the NC separation mechanism illustrated in Figure 1, the nanocapillary is required to have a charged inner surface to achieve differential retentions. Otherwise, all species (cations, anions and neutral compounds) will be evenly distributed inside the nanocapillary, and will move at the same speed as the eluent (NC Feature 3). To validate this, we replaced the bare nanocapillary with an HPC-coated nanocapillary. The residual zeta potential in an HPC-coated capillary was estimated to be less than 1 mV based on the electroosmotic mobility data after derivatization [41]. When the HPC-coated nanocapillary was used to separate BCECF, fluorescein and rhodamine B under the same conditions as indicated for the top chromatogram of Figure 3. The three compounds were eluted out unresolved (data not shown), which proved the necessity of a charged surface (ζ ≠ 0) for NC separations.

To demonstrate the feasibility of NC for practical uses, we used this method for DNA separations, and Figure 10 presents the results. The DNA fragments ranges from 75 bp to 20 kbp, and excellent resolutions were obtained. Many of the peaks had efficiencies of more than 100 000 plates per meter. It should be pointed out that separations of large DNA molecules are usually carried out by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. The results shown in this paper demonstrated that NC could separate not only small ions but also large DNA fragments, and separations of both small and large DNA molecules could be accomplished in a single run. The large DNA molecules have radii of up to 350 nm [42] when coiled. Were they coiled or stretched during NC separations? At this stage, the exact separation mechanism of these molecules is unclear. We assume it to be a combination of NC, hydrodynamic separation [38,39] and radial migration [40]. Studies on this are undergoing, and the results will be published elsewhere.

Figure 10. NC separations of DNA fragments.

The separation capillary had a radius of 500 nm and a total length of 46 cm (42 cm effective). The sample injection conditions were 10 s at 100 psi, and the separations were carried out at 100 psi. The separation traces were respectively obtained using 10 mM TE buffer as eluent. Trace a – 1 kbp DNA ladder, and trace b – 100 bp DNA ladder.

Other noticeable features of these separations were the small sample volume injected (less than 1 pL per run) and little eluent consumed (less than 0.1 nL per run). The waste generation and cost of consumables were almost negligible in running NC separations.

4. CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated the feasibility of NC for separations of ionic analytes. NC separations offer low consumable cost, and generate little waste. Separation efficiencies of more than 100 000 plates per meter are routinely obtained. At this stage, only 500~800-nm-radius capillaries were used due to the unavailability of narrower capillaries. We expect the efficiencies to be further improved via utilization of smaller capillaries. With the capability of current micro-and nano-fabrication technologies, low-nanometer-deep channels have been produced on a microchip device using various materials [6–12]. This could solve the problem of the unavailability of narrow capillaries. We have developed a model to predict the retention behavior of ions in both nanocapillaries and nano-slit channels (unpublished results), and the same elution order was obtained in both cases. Since NC separations do not require external electric fields, silicon wafers can be used to produce on-chip nanochannel columns. This could broaden the applications of micro- and nano-fluidic devices considerably, because technologies are readily available to construct 3-dimensional fluidic networks and integrate multi-functional components (many of these components are already fabricated) on a single silicon chip device. It should keep in mind that, when the depth of a nanochannel is reduced, the decreased sample loading capacity and the diminished analyte signal will bring difficulties to NC. If a long and shallow channel is used, introduction of an adequate pressure to the chip device could be another challenge. Compromises may have to be made between resolution and operation convenience in practice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work is partially supported by NIH (1 RO1 GM078592-01), NSF (CHE-0514706), and the Texas Advanced Research Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pu Q, Yun J, Temkin H, Liu S. Nano Lett. 2004;4:1099–1103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tas NR, Mela P, Kramer T, Berenschot JW, van den Berg A. Nano Lett. 2003;3:1537–1540. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein D, van der Heyden FHJ, Koopmans WJA, Dekker C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:15853–15858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605900103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu S, Pu Q, Gao L, Korzeniewski C, Matzke C. Nano Lett. 2005;7:1389–1393. doi: 10.1021/nl050712t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang YC, Stevens AL, Han J. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:4293–4299. doi: 10.1021/ac050321z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia AL, Ista LK, Petsev DN, O'Brien MJ, Bisong P, Mammoli AA, Brueck SRJ, Lopez GP. Lab Chip. 2005;5:1271–1276. doi: 10.1039/b503914b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bluhm EA, Bauer E, Chamberlin RM, Abney KD, Young JS, Jarvinen GD. Langmuir. 1999;15:8668–8672. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, Cao X, Jiang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:764–765. doi: 10.1021/ja068165g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong CC, Agarwal A, Balasubramanian N, Kwong DL. Nanotechnology. 2007;18:135304. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/18/13/135304. (6pp) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C, Yang EH, Myung NV, George T. Nano Lett. 2003;3:1339–1340. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hug TS, de. Rooij NF, Staufer U. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2006;2:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo LJ, Cheng X, Chou CF. Nano Lett. 2004;4:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pennathur S, Santiago JG. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6782–6789. doi: 10.1021/ac0508346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olivera BM, Baine P, Davidson N. Biopolymers. 1964;2:245–257. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson N, Alarie JP, Ramsey JM. In: Polyelectrolyte Transport in Nanoconfined Channels, Squaw Valley, CA, 2003. Northrup A, editor. Vol. 1. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2003. pp. 701–703. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pennathur S, Santiago JG. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6772–6781. doi: 10.1021/ac050835y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han J, Craighead HG. Proc. SPIE-Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2000;4177:42–48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han J, Craighead HG. Science. 2000;288:1026–1029. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han J, Craighead HG. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A. 1999;17:2142. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han J, Turner SW, Craighead HG. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999;83:1688–1691. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han J, Craighead HG. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:394–401. doi: 10.1021/ac0107002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgeen D, Nakache FR. J. Phys. Chem. 1964;68:1084–1091. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter RJ. Zeta Potential in Colloid Science Principles and Applications. London: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S, Pu Q, Byun CK, Wang S, Lu J, Xiong Y. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:10818–10823. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giddings JC. Sep. Sci. 1966;1:123–125. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caldwell D, Kesner LF, Meyers MN, Giddings JC. Science. 1972;176:296–298. doi: 10.1126/science.176.4032.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giddings JC. Unified Separation Science. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1991. p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheaton RM, Bauman WC. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1953;45:228–233. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novic M, Haddad PR. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1118:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xuan X, Li D. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:627–634. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice CL, Whitehead R. J. Phys. Chem. 1965;69:4017–4024. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Probstein RF. Physicochemical Hydrodynamics. 2nd ed. Wiley; 1994. p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu JJ, Liu S. Electrophoresis. 2006;19:3764–3771. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fritz JS, Gjerde DT. Ion Chromatography. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2000. pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishii D, Takeuchi T. J. Chromatogr. 1981;218:189–197. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manz A, Simon W. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 1983;21:326–330. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muller SR, Simon W, Widmer HM, Grolimund K, Schomburg G, Kolla P. Anal Chem. 1989;61:2747–2750. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noel RJ, Gooding KM, Regnier FE, Ball DM, Orr C, Mullins ME. J. Chromatogr. 1978;166:373–382. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iki N, Kim Y, Yeung ES. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:4321–4325. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng J, Yeung ES. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:3675–3680. doi: 10.1021/ac034430u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao L, Liu S. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:7179–7186. doi: 10.1021/ac049353x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oana H, Tsumoto K, Yoshikawa Y, Yoshikawa K. FEBS Lett. 2002;530:143–146. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]