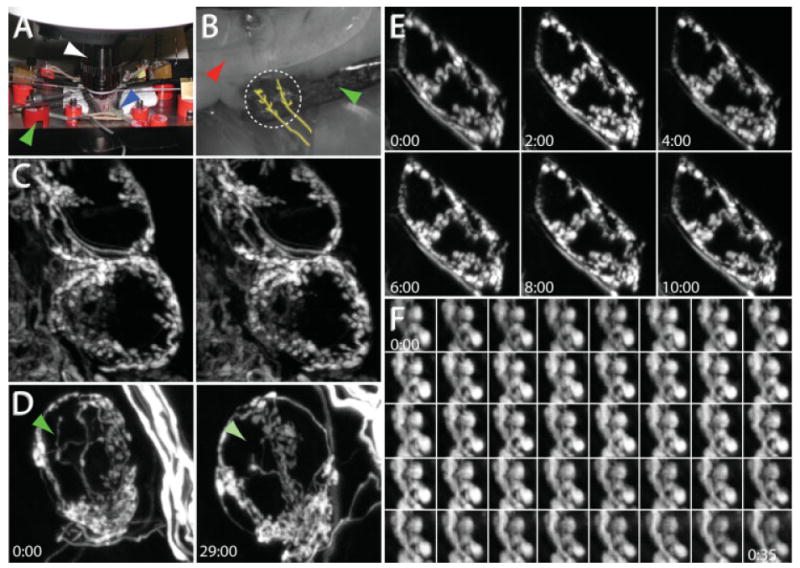

Figure 3.

In vivo time-lapse imaging in the SMG. (A) In vivo imaging setup. A 60× water immersion objective (white arrow) is placed into a cavity created by a ventral midline neck incision in an anesthetized and mechanically ventilated mouse. The blue arrow indicates the endotracheal tube connected to a small animal ventilator, and the green arrow indicates one of the retractors used to maintain the opening at the site of the neck incision. (B) The salivary ducts are placed on retractors to provide stability. One retractor (green arrow) is placed below the salivary ducts while a second retractor (red arrow) is placed on top of the submandibular gland. The location of the preganglionic axon bundles are roughly traced in yellow. The region to be imaged is indicated by the dashed white circle. (C) Stereo-pair images from an image stack depicting the preganglionic innervation to several postganglionic neurons. (D) Presynaptic axons can be visualized over days. After taking the image on the left, the neck wound was sutured closed and the animal was returned to the cage and allowed to recover. Twenty-nine hours later, the animal was reanesthetized and the same structures relocated. The green arrow indicates the location of a presynaptic terminal that was present at the beginning of the imaging session but absent the next day. (E) Presynaptic axons can be visualized chronically over hours. YFP-labeled preganglionic axons were stable when imaged every 2 h for 10 h. (D, E) Times indicate hours:minutes. (F) Presynaptic boutons imaged every minute for 35 min. Times represent minutes:seconds.