Abstract

Objectives

To elucidate the visual significance of the foveal pit by measuring foveal architecture and function and to reassess use of the term foveal hypoplasia (as visual acuity can vary among patients who lack a pit).

Methods

We describe 4 patients who lack a foveal pit. Visual acuities ranged from 20/20 to 20/50. Stratus and Cirrus (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, California) optical coherence tomographs (OCTs) and multifocal electroretinograms were obtained. High-resolution retinal imaging on 2 of the participants was obtained by using a high-resolution Fourier-domain OCT and an adaptive optics flood-illuminated fundus camera.

Results

No participants had a visible foveal pit with conventional OCT. Central widening of the outer nuclear layer and lengthening of cone outer segments were seen with high-resolution Fourier-domain OCT. Adaptive op tics imaging showed normal cone diameters in the central 1° to 2°. Central multifocal electroretinogram responses were normal.

Conclusions

We show that a foveal pit is not required for foveal cone specialization, anatomically or functionally. This helps to explain the potential for good acuity in the absence of a pit and raises questions about the visual role of the foveal pit. Because the term foveal hypoplasia commonly carries a negative functional implication, it may be more proper to call the anatomic lack of a pit fovea plana.

The term foveal hypoplasia is used clinically to describe maculae in which the foveal pit is poorly demarcated. This sign is associated with poor visual acuity in a number of ophthalmic disorders, including albinism, aniridia, nanophthalmos, incontinentia pigmenti, prematurity, and retinopathy of prematurity.1-7 However, the articles describing these disorders document a surprisingly broad range of clinical expression with visual acuities from 20/20 to 20/400 in conjunction with foveal hypoplasia. Nevertheless, foveal hypoplasia is commonly thought to be responsible for the poor acuity when present, though there have been few attempts to correlate visual acuity with measures of foveal architecture and function.

A more global question concerns the purpose and value of the foveal pit. Foveal pits are found in a variety of species, including primates, birds, reptiles, and fish.8 It is generally thought that a foveal pit correlates with a region of high visual acuity, though there has been a considerable debate as to how or why the architecture of the pit is critical. The foveal pit is a zone where the inner retinal tissue, including the vasculature, is pushed to one side, leaving a clearer optical zone in the central foveola. The foveal pit usually overlies a region of cone specialization where, in humans, the cone outer segments lengthen, increase in spatial density, and are free of rods in the exact center.

We have studied several patients with foveal hypoplasia who have stable fixation and relatively good visual acuity. We correlate their visual performance with anatomic and functional measures, including high-resolution Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT), adaptive optics imaging of the cone photoreceptor array, and multifocal electroretinography (mfERG). Our results yield new insight into the relationship between foveal architecture and visual acuity, from both physiological and clinical vantage points. The results suggest that the term foveal hypoplasia can be ambiguous and perhaps should be augmented with a more anatomic descriptor of foveal flatness, fovea plana.

Methods

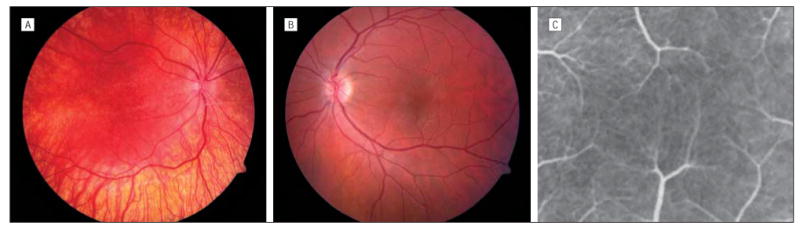

Participants provided written informed consent; we obtained approval from the institutional review board of the University of California–Davis for all specialized studies; and our investigations followed the Declaration of Helsinki. Four participants were studied, all of whom showed absence or near absence of a foveal pit or foveal avascular zone on clinical examination (Figure 1). All had mildly reduced visual acuity but stable fixation and no nystagmus. Clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. Patient 1 is a 20-year-old male college student who had partial oculocutaneous albinism diagnosed 15 years earlier. He had no family history of albinism or other retinal diseases. He has very pale skin and blond hair and is the only blond individual in his family. He has no visual complaints. Patient 2 is a 26-year-old woman with tawny hair and irides, though her family was typically very dark haired. Her fundi were not albinotic, but she lacked the normal zone of increased foveal pigmentation. Patient 3 is a 10-year-old boy with very albinotic fundi and pale hair relative to other family members. Patient 4 is a 26-year-old man with normal skin, brown hair, and tawny irides (which were not unusual for his family). His fundi were similar to those of patient 2. Patients 1 and 3 were thought to likely represent partial (presumed tyrosinase-positive) oculocutaneous albinism. Patients 2 and 4 were not clearly albinotic and may represent idiopathic cases.

Figure 1.

Clinical appearance of the retina. A, Fundus photograph of patient 3. Patients 1 and 3 appeared similar, being very albinotic except for central pigment dusting. B, Fundus photograph of patient 2. Patients 2 and 4 had normal peripheral fundus pigmentation in general but no foveal demarcation or pit. C, Fluorescein angiogram of patient 2, enlarged to show vessels crossing the central zone (absence of a foveal avascular zone).

Table 1. Patient Clinical Findings.

| Patient

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sex | M | F | M | M |

| Age, y | 20 | 26 | 10 | 26 |

| General fundus pigmentation | Albinotic | Normal | Albinotic | Normal |

| Visual acuity | • 20/25 | 20/30 | 20/40-20/50 | 20/20-20/25 |

| Nystagmus | None | None | None | None |

| FAZ | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Iris color | Blue | Tawny | Blue | Tawny |

| Transillumination | Speckles | None | Speckles | None |

| Foveal pit (on OCT) | None | None | None | None |

| mfERG amplitude | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

Abbreviations: FAZ, foveal avascular zone; mfERG, multifocal electroretinogram; OCT, optical coherence tomography (conventional).

Standard clinical examinations were performed, including color and red-free fundus photography for all patients and fluorescein angiography for patients 2 and 4. Conventional Stratus OCT (all patients) and spectral-domain Cirrus OCT (patient 4) were recorded (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, California). Multifocal ERGs were recorded using the VERIS system (EDI Inc, San Mateo, California). Burian-Allen electrodes were placed on each eye after pupil dilation, and the participants' eyes were refracted on the instrument. Fixation was video-monitored throughout the test. Recordings were made with an array of 103 elements using the standard International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision protocol,9 with a screen intensity of 200 candelas (cd)/m2 for white pixels and 100 cd/m2 in the background (surround) areas of the screen. Testing was performed in dim room illumination. Data were analyzed as trace arrays, as ring averages (6 rings) from central fovea to 20° eccentricity, and as 3-dimensional displays. Microperimetry using a macular hole stimulus pattern (Goldmann I target, 200-ms presentation, 45 spots within 4° eccentricity) was performed on patient 4 using the MP-1 instrument (Nidek, Fremont, California).

High-resolution retinal images of patients 1 and 2 were acquired after dilation of the pupils with 2 bench-top laboratory instruments: a high-resolution Fourier-domain OCT10 and an adaptive optics flood-illuminated fundus camera.11 With the Fourier-domain OCT, we obtained 5-mm scans (1000 lines/frame) with a 100-microsecond line exposure (9 frames/s). The axial and lateral resolutions were approximately 4.5 μm and 10 to 15 μm, respectively. Because of the high acquisition speed, volumetric reconstruction of a retinal area 5• 5 mm was possible following image registration to correct for eye movements during the 11 seconds of scanning. The adaptive optics flood-illuminated fundus camera corrects for temporally varying higher-order aberrations of the eye to yield 1° en face images of the photoreceptor mosaic with a transverse resolution of 2.5 μm. Images at the foveal center are not as clear as at eccentric locations because foveal cone size is at the resolution limit of the system. The adaptive optics flood-illuminated en face images were taken at 3 retinal loci in patient 1 (1° temporally/superiorly; 1° nasally/inferiorly; and 2° temporally) and at 4 retinal loci in patient 2 (1°, 2°, 4°, and 7° temporally). In each region, 7 images were registered and averaged. For comparison, images were also obtained from 2 age-matched healthy controls. Cone diameter and spacing (center to center) were measured for these images in areas where the cone array was clearly visible.

Results

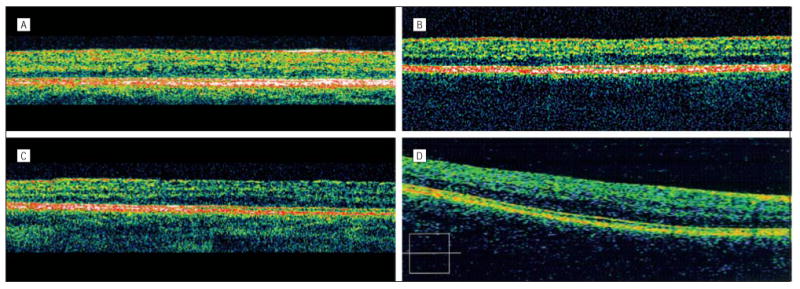

Central fixation was documented both by examination and photography with a target. Absence of a foveal avascular zone was documented by examination of fundus photographs in patients 1 and 3 and fluorescein angiography in patients 2 and 4; in all patients, vessels clearly crossed the foveal center. Conventional OCT scans (Figure 2) were taken both vertically and horizontally and through multiple sections to ensure that an eccentric or subclinical foveal zone was not missed. None of the OCT scans showed a foveal pit, and the inner retinal layers shown do not become thin or disappear as in a normal pit. There is a suggestion of outer nuclear layer widening centrally, but this is hard to define with Stratus OCT. It is seen more clearly in the spectral-domain OCT from patient 4, which also shows some central elongation of outer segments.

Figure 2.

A-C, Stratus optical coherence tomographs (OCTs) from patients 1 through 3, respectively. D, Spectral-domain (Cirrus) OCT from patient 4 (both OCTs manufactured by Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, California). Box indicates a horizontal scan.

High-resolution Fourier-domain OCT was performed on patients 1 and 2. The images (Figure 3) show no pit and in fact reveal an overall thickening of the retina in the foveal zone. This is a result of the outer segments lengthening and the outer nuclear layer widening, relative to parafoveal areas. A central elongation of foveal cones is clearly visible, though not as sharply peaked or demarcated as in the normal example (Figure 3A). Three-dimensional reconstructions show a circular zone of central thickness in place of the pit (eFigure 1; http://www.archophthalmol.com).

Figure 3.

High-resolution Fourier-domain optical coherence tomographic images. A, Control. B, Patient 1. C, Patient 2. B and C, The lengthening of cone outer segments and outer nuclear layer centrally can be seen. The nerve fiber layer is thicker nasally to encompass the conduits of central information. The Verhoeff membrane is the probable junction of retinal pigment epithelium microvilli and outer segment tips.

Adaptive optics flood-illuminated en face images of patients 1 and 2 show a regular cone mosaic, though the images from patient 1 are partly obscured by artifactual haze. Compared with a normal example at 1° eccentricity, the cone mosaic from patient 1 is similar in diameter and spacing, while that from patient 2 shows slightly larger cone diameters (Figure 4). With an increase in retinal eccentricity from 2° to 7°, there is enlargement of cone diameter and spacing comparable with what is seen in healthy eyes (Figure 5). Thus, both cases show the central narrowing and packing of cones that are components of foveal specialization. Exact comparison with healthy eyes is difficult, especially in the central 1° to 2°, because there is variation in cone diameter and spacing near the fovea among individuals with healthy eyes (eFigure 2).

Figure 4.

Adaptive optics flood-illuminated en face images of the cone array at 1° eccentricity. A, Control, temporal to fovea. B, Patient 1, nasal to fovea (temporal image showed similar spacing but had more artifactual haze). C, Patient 2, temporal to fovea.

Figure 5.

Adaptive optics flood-illuminated en face images of the cone array at different eccentricities. A-C, Control at 2° temporally, 4° temporally, and 7° nasally, respectively. D-F, Patient 2 at 2°, 4°, and 7° temporally.

The functional status of the foveal cones was assessed with mfERG in all of our participants. All eyes showed normal waveforms across the posterior pole, including the fovea (Figure 6). The signal amplitudes and ring-response densities of the main positive peak were well within the normal range for all participants at all locations, including the fovea (Table 2), and the response density in the foveal zone was clearly higher for all eyes than that in the peripheral rings. However, analysis of the ratio of response density in the fovea to that in more peripheral zones (ring ratios)12 showed that these ratios were borderline low (atypical) (Figure 7). Central macular microperimetry in patient 4 showed good fixation and no loss of sensitivity in the foveal zone.

Figure 6.

Multifocal electroretinography results from patient 1. The results from patients 2, 3, and 4 were essentially the same. A, Trace array. B, Ring analysis showing mean response density from the fovea (ring 1) out to 20° eccentricity (ring 6). C, Three-dimensional representation of signal strength. I indicates inferior; N, nasal; S, superior; T, temporal.

Table 2. Foveal Multifocal Electroretinography Responsesa.

| Patient

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Approximate Normal Range |

| Mean response density, nV/degree2 | 119 | 94 | 93 | 87 | 75-170 |

| Mean latency, ms | 30.2 | 30.9 | 27.5 | 30 | 27-33 |

The data refer to the main positive peak and are the mean of the 2 eyes.

Figure 7.

Ring ratios from multifocal electroretinography. Each point represents the ratio (mean of the 2 eyes) of the response density in the foveal region (ring 1) to that in more peripheral rings (2-6). The solid lines encompass a typical range of these ratios from a random sampling of 12 age-matched controls and are consistent with values in the literature.12 The dashed lines represent patients 1 through 4, all of whom have ratios that are borderline low, signifying that the response density in ring 1 is weak relative to surrounding areas. As noted in the “Comment” section, this could reflect a different distribution of the central cones rather than functional loss.

Comment

Independence of Cone Specialization and the Foveal Pit

Earlier reports of OCT findings in foveal hypoplasia have shown that a pit may be lacking in individuals with a spectrum of visual acuities from good to poor.7,13-16 Our cases add a critical element: foveal cone specialization can be preserved both anatomically and functionally despite the absence of a pit.

Our observed central lengthening of cone outer segments and widening of the outer nuclear layer explain the overall thickening of the central retina and presumably account for the normal mfERG responses. It is not clear whether the broader distribution of the elongated foveal cones in these patients has any visual significance. The array of central cones at 1° and 2° eccentricity was generally comparable with that in healthy eyes,17 though patient 2 showed larger cone diameters and less-dense central packing than patient 1. This may represent a physiologic difference but could be normal variation in anatomy or in the fixation point on the retina (which is difficult to quantify with our methodology).

Apparently, neither a foveal avascular zone nor a pit is critical to the postnatal lengthening of cones or spatial packing that presumably takes place to subserve higher visual resolution. This conclusion is consistent with other lines of evidence that separate cone specialization from the foveal avascular zone18 or concomitants of albinism, such as chiasmal misrouting.19-21 This helps to explain why visual acuity can be good in many individuals who lack foveal pits, regardless of the associated disease.

High resolution demands a sufficiently fine cone array to resolve small images and a sufficiently generous complement of integrative cells so that this information can be processed with minimal convergence of cone cells on bipolar cells. However, anatomic and mfERG measurements do not necessarily define the level of cone spacing and responsiveness that are needed to achieve standard levels of good acuity. Humans appear to have more photoreceptors and integrative connections in healthy retinas than are needed for many visual tasks. For example, many patients with retinitis pigmentosa have visual acuities of 20/20, despite foveal thinning on OCT and markedly reduced central mfERG signals. Individuals with congenital dichromatism can have visual acuities better than 20/20 despite lacking roughly one-third of their cones.22 On the other hand, poor acuity on a retinal basis is usually associated with mfERG signal loss (eg, in macular dystrophy or macular degeneration) and with foveal cone abnormalities using adaptive optic imaging (eg, in retinitis pigmentosa and cone dystrophy).11

The mfERG gives us an objective measure of cone-system function to complement the anatomic observations. A weak central mfERG, with cone response density unchanging across the posterior pole, has been reported in 2 very young children with albinism and poor visual acuity (recorded under anesthesia).23 Our findings on older individuals while awake showed responses of normal magnitude. Careful analysis of the ring amplitude (response density) ratios12 did show a subtle abnormality: the ratio of foveal amplitudes to that of surrounding rings was borderline low. This might suggest that the foveal signal was slightly weak relative to that from surrounding areas. However, this finding could also reflect the broader distribution of specialized foveal cones, since this would affect loci of retinal integration and the foveal response density as it is normally calculated. Patient 1 had slightly larger signals centrally than patient 2 (Table 2), which could reflect their differences in cone density. However, this amplitude disparity is well within normal variability, and the responses from case 1 were slightly larger all the way out to 20° eccentricity. Subjective testing of central field in patient 4 was consistent with the mfERG results, insofar as there was no loss of sensitivity. It will be of interest in the future to see how other psychophysical measures of retinal integration might relate to the retinal morphology of these cases.

Visual Importance of the Foveal Pit

Our anatomic and mfERG data show some of the reasons why lack of a pit does not preclude good visual acuity. Of course, it is possible that some patients who lack pits and have poor visual acuity do in fact have poor central cone development as well. Depressed foveal mfERG signals were reported in the 2 children recorded under anesthesia,23 and some histopathologic reports (albeit from less than ideal material) have hinted at cone anatomic abnormalities.24-26 Unfortunately, cases with low acuity are difficult to study with mfERG or high-resolution imaging because of poor fixation and nystagmus. A study of grating acuities in 2 albino patients with poor visual acuity concluded that they had increased cone spacing and arrested cone development.27 Visual loss in such patients could also result from central abnormalities associated with chiasmatic maldevelopment and may be compounded by nystagmus.19,21

Why then do we have a pit? It is possible that pits serve optically to fine-tune acuity beyond the neural requirements. Raptor birds (and some reptiles and fish) have extremely steep foveal pits that may cause a modest degree of image magnification from refraction on the steep pit walls (• 15%).8,28 This effect would be much smaller in humans, and some authors have even questioned its role in raptors.29,30 Raptor acuity has been estimated anecdotally as being up to 8 times better than ours,31 though recent studies have documented them as having acuities of only 2 to 4 times better.30,32-34 Raptor cones are tightly packed and likely show less cone-to-bipolar convergence.30,33-35 Raptor corneas are also very clear and may have less aberration than in humans. The lack of overlying tissue and vessels in the human fovea undoubtedly provides some optical advantage to the central cones, though it is probably not large. It may be a confluence of these factors that allows optimal acuity.

Fovea Plana vs Foveal Hypoplasia

Is there a clinical message from these results? Our data demonstrate that we should not view the lack of a foveal pit as an absolute concomitant of poor visual acuity. Nevertheless, from a practical standpoint, poor pit morphology remains a useful warning sign that should raise concerns in either infants or adults, as it is often associated with either reduced acuity or a history of ocular pathology. Like many signs in clinical medicine, it should neither be ignored nor taken as gospel, but it should be interpreted within the context of clinical history and physical findings.

Our findings suggest that the clinical terminology for foveal morphology should be reexamined. The term fovea simply means “pit” in Latin, so that foveal hypoplasia in its narrowest interpretation means no more than a loss of the pit (without implications for foveal cones or for visual acuity). However, in common clinical usage, the term fovea is used for all of the centrally specialized structures and is synonymous with our anatomic and physical apparatus for high visual resolution. The term foveal hypoplasia is commonly used to imply a lack of these collective structures needed for good visual acuity.

There are 2 potential solutions to this semantic dilemma. One is to recognize that the term foveal hypoplasia could refer to loss of the pit and/or cone specialization independently. In other words, the term would not be interpreted as indicative of poor vision or even necessarily of a lack of pit (since foveal cones might in some cases be poorly specialized and hypoplastic within a pit). However, refocusing an old and familiar term is often difficult. A better alternative may be to introduce a new term for the anatomic lack of a central pit, a term that does not carry any functional implications. We propose that the term fovea plana may serve this purpose as a purely anatomic description (which means quite simply “flat pit”). Patients observed clinically to lack pits, whether from albinism, aniridia, retinopathy of prematurity, or other causes, would thus be described as having fovea plana, though the visual consequences and status of the foveal cones could vary widely among such patients and would remain to be determined in each case.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant EY014743 from the National Eye Institute (Dr Werner) and Research to Prevent Blindness (senior scientific investigator award, Dr Werner).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Previous Presentation: This paper was presented by Dr Marmor as the 2007 W. Richard Green Lecture of the Macula Society; June 2007; London, England.

Additional Information: eFigures are available at http://www.archophthalmol.com.

References

- 1.Summers CG, Creel D, Townsend D, King RA. Variable expression of vision in sibs with albinism. Am J Med Genet. 1991;40(3):327–331. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320400316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charles SJ, Green JS, Grant JW, Yates JR, Moore AT. Clinical features of affected males with X linked ocular albinism. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77(4):222–227. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.4.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorey SE, Neveu MM, Burton LC, Sloper JJ, Holder GE. The clinical features of albinism and their correlation with visual evoked potentials. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(6):767–772. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.6.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi MM, Trese MT, Capone A., Jr Optical coherence tomography findings in stage 4A retinopathy of prematurity: a theory for visual variability. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(4):657–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg MF, Custis PH. Retinal and other manifestations of incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome) Ophthalmology. 1993;100(11):1645–1654. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh MK, Goldberg MF. Abnormal foveal avascular zone in nanophthalmos. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(6):1067–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Recchia FM, Recchia CC. Foveal dysplasia evident by optical coherence tomography in patients with a history of retinopathy of prematurity. Retina. 2007;27(9):1221–1226. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318068de2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walls G. Significance of the foveal depression. Arch Ophthalmol. 1937;18(6):912–919. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marmor MF, Hood DC, Keating D, Kondo M, Seeliger MW, Miyake Y. International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision. Guidelines for basic multifocal electroretinography (mfERG) Doc Ophthalmol. 2003;106(2):105–115. doi: 10.1023/a:1022591317907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Doc Ophthalmol. 2003;106(3):338. erratum published in. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zawadzki RJ, Fuller AR, Wiley DF, Hamann B, Choi SS, Werner JS. Adaptation of a support vector machine algorithm for segmentation and visualization of retinal structures in volumetric optical coherence tomography data sets. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12(4):041206. doi: 10.1117/1.2772658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi SS, Doble N, Hardy JL, et al. In-vivo imaging of the photoreceptor mosaic in retinal dystrophies and correlations with retinal function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(5):2080–2092. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyons JS, Severns ML. Detection of early hydroxychloroquine retinal toxicity enhanced by ring ratio analysis of multifocal electroretinography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(5):801–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer CH, Lapolice DJ, Freedman SF. Foveal hypoplasia in oculocutaneous albinism demonstrated by optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(3):409–410. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Recchia FM, Carvalho-Recchia CA, Trese MT. Optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis of foveal hypoplasia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(11):1587–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuire DE, Weinreb RN, Goldbaum MH. Foveal hypoplasia demonstrated in vivo with optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(1):112–114. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01923-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey PS, King RA, Summers CG. Spectrum of foveal development in albinism detected with optical coherence tomography. J AAPOS. 2006;10(3):237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curcio CA, Sloan KR, Kalina RE, Hendrickson AE. Human photoreceptor topography. J Comp Neurol. 1990;292(4):497–523. doi: 10.1002/cne.902920402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendrickson A, Hidayat D, Erickson A, Possin D. Development of the human retina in the absence of ganglion cells. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83(4):920–931. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Genderen MM, Riemslag FCC, Schuil J, Hoeben FP, Stilmo JS, Meire FM. Chiasmal misrouting and foveal hypoplasia without albinism. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(9):1098–1102. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.091702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neveu MM, Holder GE, Sloper JJ, Jeffery G. Optic chiasm formation in humans is independent of foveal development. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22(7):1825–1829. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sloper J. Chicken and egg. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(9):1074–1075. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.097618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll J, Neitz M, Hofer H, Neitz J, Williams DR. Functional photoreceptor loss revealed with adaptive optics: an alternate cause of color blindness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(22):8461–8466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401440101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly JP, Weiss AH. Topographical retinal function in oculocutaneous albinism. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(6):1156–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naumann GO, Lerche W, Schroeder W. Foveolar aplasia in tyrosinase-positive oculocutaneous albinism (author's translation) [in German] Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1976;200(1):39–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00411431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Donnell FE, Hambrick GW, Green WR, Iliff WJ, Stone DL. X-linked ocular albinism: an oculocutaneous macromelanosomal disorder. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976;94(11):1883–1892. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1976.03910040593001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fulton AB, Albert DM, Craft JL. Human albinism: light and electron microscopy study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96(2):305–310. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910050173014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson HR, Mets MB, Nagy SE, Kressel AB. Albino spatial vision as an instance of arrested visual development. Vision Res. 1988;28(9):979–990. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(88)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder AW, Miller WH. Telephoto lens system of falconiform eyes. Nature. 1978;275(5676):127–129. doi: 10.1038/275127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dvorak D, Mark R, Reymond L. Factors underlying falcon grating acuity. Nature. 1983;303(5919):729–730. doi: 10.1038/303729b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin GR. Shortcomings of an eagle's eye. Nature. 1986;319(6052):357. doi: 10.1038/319357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walls GL. The Vertebrate Eye and Its Adaptive Radiation. Cranbrook Press; Bloomfield Hills MI: 1942. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaffney MF, Hodos W. The visual acuity and refractive state of the American kestral (Falco sparverius) Vision Res. 2003;43(19):2053–2059. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(03)00304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reymond L. Spatial visual acuity of the falcon, Falco berigora: a behavioural, optical and anatomical investigation. Vision Res. 1987;27(10):1859–1874. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reymond L. Spatial visual acuity of the eagle Aquila audas: a behavioural, optical, and anatomical investigation. Vision Res. 1985;25(10):1477–1491. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Güntürkün O. Sensory physiology: vision. In: Whittow GC, editor. Sturkie's Avian Physiology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]