What makes an unspecialized cell become heart or skin or brain or tumor? The answer—or at least part of it—lies in the presence of proteins that attach to DNA and act like switches to turn on transcription in genes that are involved in guiding that cell toward one destiny or another. The presence of such proteins, in turn, depends on an elaborate system for silencing and activating the genes that make them. Scientists are only beginning to understand this system, which they hope to manipulate to use stem cells for therapeutic purposes and to stop the development of cancer cells.

In a new study, Stephen Baylin, Vijay Tiwari, and colleagues shed light on this gene regulation system by exploring the silencing and activation of a gene, Gata-4, that is implicated in switching on genes that promote cell differentiation and—when abnormally suppressed—in promoting tumor development. The researchers focused on Polycomb group (PcG) proteins, which attach to large stretches of DNA in early embryonic cells to help keep key developmental regulatory genes at a low level of expression, but disappear when the cells begin to differentiate. Studies in fruit flies and mammals suggest that PcG proteins are involved in regulating the transcription of these regulatory genes. But it's not clear how PcG proteins—particularly those not near the genes—exert their influence. It's also not clear how PcGs interact with DNA methylation—the attachment of methyl groups, like bits of bling, to DNA that is known to be involved in keeping genes turned off.

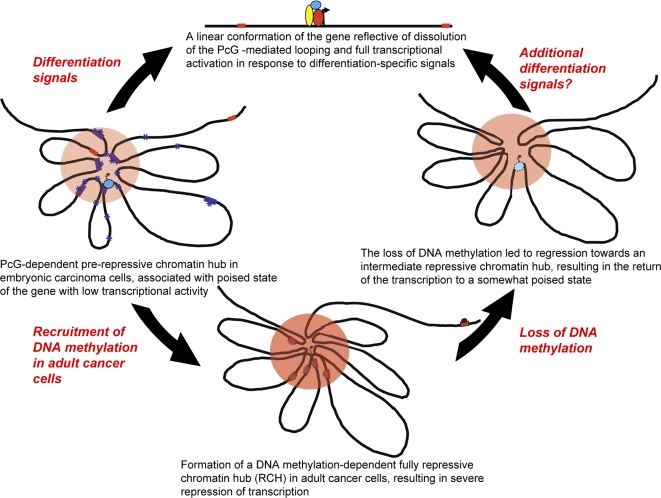

To learn more about PcG's role in regulatory gene silencing and activation, Baylin, Tiwari, and colleagues tapped a variety of biochemical tools to look at the molecular makeup of chromatin in the vicinity of Gata-4 under various circumstances in four kinds of cells: undifferentiated embryonic carcinoma cells (Tera-2), in which Gata-4 is expressed at a low rate; Tera-2 cells that had been induced to differentiate and in which Gata-4 is expressed at very high levels; adult colon cancer cells, in which Gata-4 is fully silenced and the DNA near Gata-4 is hypermethylated; and adult colon cancer cells that were genetically altered so that DNA was not methylated around Gata-4 and Gata-4 is re-expressed, but at a low level.

The “loopiness” of chromatin around a target gene influences the gene's level of transcriptional activation.

Using two techniques designed to determine how various chromatin (the DNA–protein network that makes up chromosomes) regions physically situate with respect to each other within the chromosome—associated chromosome trap (ACT) assay and chromosome conformation capture (3C) analysis—the researchers found that distant portions of chromatin interacted with Gata-4 in Tera-2 cells, creating chromatin loops that clustered around it. With the chromatin in this configuration, Gata-4 was expressed at a low level. A similar analysis on Tera-2 cells that had been induced to differentiate showed that the interactions had disappeared and the chromatin was almost linear with respect to the original loops, suggesting that the loops were related to transcription potential.

Applying the same tests to adult colon cancer cells, the researchers found that chromatin was super-loopy in the hypermethylated, super-silenced version. In the cells that had been genetically altered to eliminate methylation, however, Gata-4 was expressed at a low rate, and loops were present but less abundant—a state reminiscent of the undifferentiated Tera-2 cells. These results indicate that loops and gene silencing are related.

To further elucidate the role of PcG proteins, the researchers looked for various forms of PcG related to another kind of methylated area (called histone marks) along the chromatin on either side of Gata-4. They found that the PcGs occurred far upstream and downstream of the gene in undifferentiated Tera-2, but disappeared in the cells that had begun to differentiate. The adult colon cancer cells showed levels of PcG and associated marks at the Gata-4 gene that were lower than those in the Tera-2 cells but higher than those found in very active genes in the adult cancer cells.

Together, these findings suggest that the PcGs and histone marks might be helping to silence the gene through the looping process. To test this, the researchers applied RNA interference to deplete PcGs in Tera-2 cells. They found that loopiness decreased and transcription increased slightly— strong evidence that PcGs play a role in the looping. Similarly, in the silenced adult colon cancer cells, but not in the ones expressing Gata-4, methylated bits of DNA occur a long distance from the gene and are brought close to the gene by looping, providing additional evidence that chromatin loopiness works to silence Gata-4. The researchers concluded that chromatin looping mediates a “poised” (low expression) state by bringing transcription-blocking PcG and associated histone marks close to the gene in embryonic cells, and that a similar state, when associated with DNA hypermethylation, leads to super-silencing in adult colon cancer cells.

The researchers note that their findings have important implications for cancer treatment and prevention. They show that gene silencing is more complicated than previously thought based on a linear rather than looped chromatin configuration. Thus, the cause and effect of loopiness will need to be taken into consideration in future efforts to explore the modification of silencing of key genes such as Gata-4 as a tool for preventing or treating cancer.