Abstract

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Although various drugs are available for the treatment of CHB, emergence of the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)‐negative mutant variant, specifically in Asia, the Middle East and southern Europe, is creating a new challenge as this variant is less responsive to available treatments. HBeAg‐negative CHB rapidly progresses to cirrhosis and its related complications. This review discusses the available literature on the approved and under‐trial treatment options and their respective efficacies for HBeAg‐negative CHB.

Keywords: chronic hepatitis B, HbeAg negative, resistant, entecavir, lamivudine, combination therapy

Chronic hepatitis virus B (CHB) infection is a major global public health problem, with an estimated 1 million deaths per year worldwide from HBV‐related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver failure.1,2 There is spontaneous clearance of the virus in 90–95% patients within 6 months after acute hepatitis due to hepatitis B virus (HBV). Only 5–10% patients progress to chronic state, which is associated with considerable mortality and morbidity.3 If, however, HBV infection is acquired in childhood, 90% of the patients progress to chronic state. At least 20–30% of hepatitis B surface antigen‐positive carriers die from complications of cirrhosis and HCC.4 Although treatment of CHB is available, the emergence of precore and core promoter mutations results in poor sustained virological and biochemical response and rapid progression to cirrhosis.

HBeAg‐negative CHB

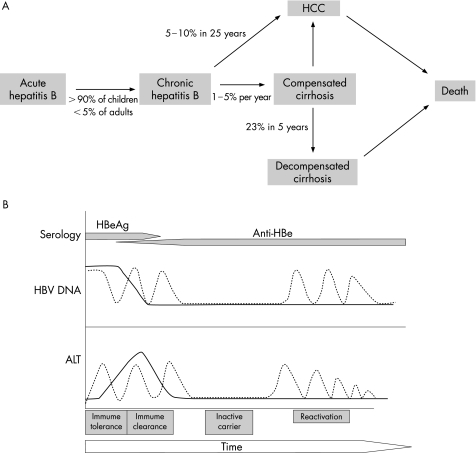

CHB can be broadly divided into two major forms—namely, hepatitis B virus e antigen (HBeAg) positive and HBeAg negative. Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)‐negative CHB is also referred to as anti‐HBe‐positive and precore mutant hepatitis. Patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB have a naturally occurring mutant form of HBV that does not produce HBeAg because of a mutation in the precore or core promoter region of the HBV genome. The most frequent precore mutation is a G→A change at nucleotide 1896 (G1896A), which creates a stop codon and results in loss of HBeAg synthesis. The most common core promoter mutation involves a two‐nucleotide substitution at nucleotides 1762 and 1764.5,6 Figure 1 shows the natural history of HBV infection. HBeAg‐negative carriers are a heterogeneous group and most of them have low viral DNA levels(<104 copies/ml), relatively normal levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and a fair prognosis. However, in Asia, the Middle East, Mediterranean basin and southern Europe, about 15–20% of these carriers have raised ALT and high viral DNA (>104 copies/ml).7 HBeAg‐negative CHB emerges during the course of a typical HBV infection with the wild‐type virus, and is selected during the immune clearance phase (HBeAg seroconversion).8 HBeAg‐negative CHB can develop either soon after HBeAg seroconversion or decades later. As many as 30–40% of patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB experience persistently raised ALT levels (3–4‐fold), and the remaining 60–70% patients can have fluctuating levels of ALT (“flares”) and tend to be more refractory to antiviral treatment. With available treatment options, sustained remission occurs in only 6–15% of these individuals, and spontaneous clearance of the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is seen in only about 0.5% of patients per year.9 HBeAg‐negative CHB usually has an aggressive course, with rapid progression to cirrhosis and frequent development of HCC.10 The annual rate of progression to cirrhosis is 8–10% in HBeAg‐negative patients compared with 2–5% in HBeAg‐positive patients.10 Long‐term prognosis is poorer among HBeAg‐negative individuals compared with their HBeAg‐positive counterparts.10 Therefore, appropriate use of effective therapy is an important issue in the management of this group of patients.

Figure 1 (A) Progression of hepatitis B‐related liver disease. (B) Natural history of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBe, hepatitis B e antigen; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Goals of treatment

The goals of treatment are to achieve

sustained suppression of the HBV DNA levels;

normalisation of ALT levels;

delay or arrest in the progression of liver injury and development of cirrhosis and HCC.

Complete eradication of HBV is difficult because of its tendency to integrate into the host genome. Patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB generally require longer duration of treatment than those with HBeAg‐positive CHB, particularly when oral treatment is used. The recommended ALT levels for treatment initiation in these patients is different, as the levels of ALT often fluctuate and may even be normal. As about 50% of HBeAg‐negative patients have active liver disease with HBV DNA levels <105 copies/ml,11,12 the HBV DNA threshold to start the treatment is lower at ⩾104 copies/ml.

Response of CHB to antiviral treatment has been categorised as biochemical, virological or histological, and as on therapy or sustained off therapy (table 1).13

Table 1 Responses to antiviral treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| Category of response | |

| Biochemical | Decrease in serum ALT to within the normal range |

| Virological | Decrease in serum HBV DNA to undetectable levels in unamplified assays (<105 copies/ml) and loss of HBeAg in patients who were initially HBeAg positive |

| Histological | Decrease in histology activity index by at least 2 points compared with pretreatment liver biopsy |

| Complete | Fulfil criteria of biochemical and virological response and loss of HBsAg |

| Time of assessment | |

| On therapy | |

| Maintained: Persist throughout the course of treatment | |

| End of treatment: At the end of a defined course of treatment | |

| Off therapy: After discontinuation of treatment | |

| Sustained (SR6): 6 months after discontinuation of treatment | |

| Sustained (SR12): 12 months after discontinuation of treatment | |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

The available treatment options for HBeAg‐negative CHB are as follows:

Interferon (IFN)

PEGylated IFN

Lamivudine

Adefovir

Entecavir

IFN in HBeAg‐negative CHB

The therapeutic effects of IFNα are secondary to its antiviral, antiproliferative and immunomodulatory properties. High pretreatment ALT and lower levels of serum HBV DNA are the most important predictors of response to IFN.14 IFN is usually given subcutaneously in a dose of either 5 million units daily or 10 million units three times weekly for 12 months. Several published studies have reported using IFN for HBeAg‐negative CHB. Manesis and Hadziyannis,12 in a retrospective study, found that IFN induced long‐term (median follow‐up of 7 years) biochemical and virological remission in about 18% of naive or retreated patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB. Sustained responders showed considerable histological improvement and a high rate of HBsAg loss (32%).

In four different randomised controlled trials15,16,17,18 which included 86 patients receiving therapy with IFN and 84 untreated patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB, a 38–90% end‐of‐treatment response (ETR) was seen in the treated group compared with 0–37% in the untreated group. The sustained rate 12 months after discontinuation of treatment was 10–47% (average 24%) in the treated group compared with 0% in the untreated group.

Brunetto et al19 used 9 million units IFNα twice weekly for 4–12 months in 57 patients and other IFN regimens in 46 patients, and they showed the beneficial effect of IFNα in patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB. The ETR rate was 68.5%. Overall relapse rate among initial responders was 78% and the sustained rate among end‐of‐treatment responders was 21%. In addition, 66% with sustained response lost HBsAg and 50% of them developed anti‐HBs antibodies.

In another study from Greece,20 147 patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB who had undergone ⩾2 liver biopsies and had been treated with IFNα (n = 120) or had remained untreated (n = 27) were evaluated for improvement in fibrosis. The median interval between the two biopsies was 24 (range 12–160) months. The authors concluded that in HBeAg‐negative CHB, IFNα markedly reduces the rate of fibrosis progression, but such an effect was mainly observed in patients with sustained biochemical responses. In relapsers and non‐responders, fibrosis benefit equalled the treatment period. The strongest factor associated with fibrosis progression was the change in necroinflammatory activity.

IFN treatment markedly improves the necroinflammatory activity and reduces the rate of progression of fibrosis, mainly in patients with sustained response.21,22

PEGylated IFN

PEGylation is the process by which a polyethylene glycol moiety is attached to a protein or a drug to decrease renal clearance and increase bioavailability and efficacy. The two forms of PEG‐IFN—PEG‐IFNα2a (Pegasys) and PEG‐IFNα2b (Pegintron)—differ in their molecular weight. PEG‐IFNα2a, like conventional IFN, has dual immunomodulatory and antiviral activity and yields superior clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C and CHB. In a phase II study, 194 patients with HBeAg‐positive CHB, not having received treatment previously, treated with conventional IFNα, were randomised to receive PEG‐IFNα2a (40 kDa) 90, 180 or 270μg weekly, or conventional IFNα2a 4.5 MIU three times weekly. The patients were assessed for loss of HBeAg, presence of hepatitis B antibody (anti‐HBe), suppression of HBV DNA, and normalisation of serum ALT after follow‐up. At the end of follow‐up, HBeAg was cleared in 37%, 35% and 29% of patients receiving PEG‐IFNα2a (40 kDa) 90, 180 and 270μg, respectively, compared with clearance in 25% of patients receiving conventional IFNα2a. The combined response (HBeAg loss, HBV DNA suppression and ALT normalisation) of all PEG‐IFNα2a (40 kDa) doses combined was two times that achieved with conventional IFNα2a (24% v 12%; p = 0.036). All treatment groups were similar with respect to frequency and severity of adverse events. Thus, Peg‐IFNα2a (40 kDa) was superior in efficacy to conventional IFNα2a in treatment of patients with CHB, on the basis of clearance of HBeAg, suppression of HBV DNA and normalisation of ALT.23

Efficacy of PEG‐IFNα2a has also been proved in patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB. A large multicentre study compared PEG‐IFNα2a monotherapy, PEG‐IFNα2a plus lamivudine combination therapy and lamivudine monotherapy in HBeAg‐negative CHB for 48 weeks. The percentages of patients with sustained HBV DNA levels <20 000 copies/ml after 24 weeks' follow‐up were 43%, 44% and 29%, respectively, in the three groups.24 Marcellin et al25 reported follow‐up data for this trial. They presented 96‐week data (48 weeks after the end of treatment) for 57% of the patients for whom data were available from the original study group. At week 96, HBV DNA suppression to <400 copies/ml was seen in 17%, 14% and 8% of patients from the PEG‐IFN only, PEG‐IFN plus lamivudine and lamivudine only groups, respectively. The rationale for using PEGylated IFN‐based therapy for the treatment of the HBeAg‐negative patient derives from the finite treatment course, although <20% of patients will have long‐term viral suppression. Unfortunately, most patients will not have prolonged benefit, and will have to experience the potential adverse events associated with IFN‐based treatment for 1 year.

Lamivudine: epivir‐HBV, active triphosphate

Lamivudine is the (−) enantiomer of 2′‐3′dideoxy‐3′‐thiacytidine. Incorporation of the active triphosphate into growing DNA chains results in premature chain termination, thereby inhibiting HBV DNA synthesis. Lamivudine monotherapy is currently a therapeutic option for patients with CHB irrespective of HBeAg status.13 Treatment with lamivudine 100 mg/day leads to histological improvement, with HBeAg seroconversion in 16–18% of patients after 1 year of treatment and in 50% of patients after 5 years. ALT normalisation occurs in 41–72% of patients and HBV DNA suppression in 44% of patients in HBeAg‐positive CHB.26,27,28

Although most of the clinical trials of lamivudine are with HBeAg‐positive patients, a few studies have reported an appreciable beneficial effect in patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB. In patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB, a 12‐month course of lamivudine had a satisfactory ETR, with complete response in two thirds of patients.29 Patients were randomised to receive 100 mg lamivudine orally once daily for 52 weeks or placebo for 26 weeks. Patients who were HBV DNA positive at week 24 were withdrawn at week 26. The primary efficacy end point was loss of serum HBV DNA and normalisation of ALT at week 24. A considerably higher proportion of patients receiving lamivudine (63%) had a complete response at week 24 compared with patients receiving placebo (6%). Secondary end point included histological response from baseline to week 52 in the lamivudine‐treated patients. At week 52, 60% of lamivudine‐treated patients whose liver biopsy specimens were available showed histological improvement (⩾2‐point reduction in the Knodell necroinflammatory score), 29% showed no change and 12% worsened. At week 52, 27% of patients receiving lamivudine had the YMDD (tyrosine methionine d‐aspartate d‐aspartate) amino acid motif of the HBV polymerase variant HBV. This mutation leads to flaring up of the disease activity and rapid progression to cirrhosis. The incidence of adverse events and laboratory abnormalities was similar in both groups. But this beneficial effect was not maintained when treatment was withdrawn.29 A high pretreatment viral load is the determinant for early biochemical relapse.27

Other studies have also shown the efficacy of lamivudine in patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB.30,31,32,33 Most of the studies have shown a virological and biochemical response in as many as 70% of the treated patients. Unfortunately, >90% of the patients showed relapsed when treatment was stopped.34 Also, extending the duration of treatment results in a progressively lower rate of response as a result of the selection of lamivudine‐resistant mutants.35

The efficacy of long‐term lamivudine monotherapy in patients with decompensated HBeAg‐negative or HBV‐DNA‐positive cirrhosis has been evaluated. In one study,36 marked clinical improvement, defined as a reduction of at least two points in Child–Pugh score, was observed in 23 of the 30 (76.6%) treated patients compared with none of the 30 patients in the control group after a mean (standard deviation) follow‐up of 20.6 (12.1) months. The number of patients dying because of liver disease was markedly more in the untreated group. Liver‐related deaths occurred in five of the eight patients soon after the development of biochemical breakthrough. Patients with clinical improvement had better survival than those with no improvement or those who developed biochemical breakthrough because of YMDD mutants. In another study37 that included 20 patients awaiting liver transplant, 9 (45%) patients had a reduction in the Child–Pugh–Turcotte score to ⩽6 (Child's class A cirrhosis). At last follow‐up, 14 (70%) patients were alive and waiting for liver transplant, with a median liver transplant‐free survival of 36 (range 12–63) months. Prolonged treatment with lamivudine results in regression of cirrhosis associated with HBeAg‐negative CHB.38

Lamivudine markedly improves liver function in HBeAg‐negative decompensated cirrhosis. However, the development of the biochemical breakthrough because of YMDD mutants is associated with fatal outcome. The end point of treatment for HBeAg‐negative CHB is unknown.

Adefovir

Adefovir is a nucleotide analogue of adenosine monophosphate. It can inhibit both the reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase activities, and is incorporated into HBV DNA causing chain termination. Adefovir dipivoxil is an orally bioavailable pro‐drug of adefovir, and is active against lamivudine‐resistant HBV mutants and the wild‐type HBV. Two large phase III randomised placebo‐controlled clinical trials of 48 weeks of adefovir treatment (10 mg/day) in patients with HBeAg‐positive39 and HBeAg‐negative40 CHB showed a higher rate of response than with placebo regarding histological improvement, normalisation of ALT and undetectable serum HBV DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In HBeAg‐negative CHB,40 adefovir dipivoxil effectively suppresses biochemical activity and HBV replication during the first 48 weeks. ALT levels normalised in 72% and 29% (p<0.001) of patients, and serum HBV DNA was undetectable by PCR in 51% and 0% of the 123 and 61 patients treated with adefovir dipivoxil and placebo, respectively (p<0.001). Moreover, at 48 weeks, histological improvement was observed in 64% of patients treated with adefovir dipivoxil and in 33% of those given placebo (p<0.001). The recommended dose of adefovir dipivoxil for CHB is 10 mg daily, irrespective of HBeAg status. Adefovir dipivoxil can be safely given at the daily dose of 10 mg in patients with hepatic or mild renal impairment, but dosing interval adjustments are recommended for patients with a creatinine clearance of <50 ml/min and patients requiring haemodialysis.41

Whether a defined course of adefovir dipivoxil may maintain a sustained response after drug discontinuation in patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB is currently not known. However, most on‐therapy responders are expected to relapse soon after discontinuation of a 48‐week course of adefovir dipivoxil, and therefore long‐term adefovir dipivoxil treatment will probably be required to maintain a sustained response. A 2‐year adefovir dipivoxil course was found to maintain on‐therapy biochemical and virological remission in both groups of patients, with HBeAg‐positive and HBeAg‐negative CHB without significant toxicity and without evidence of significant viral resistance (<2%).42,43 A recently published study showed that continued treatment with adefovir 10 mg daily in patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB for 96 weeks and up to 144 weeks resulted in persistent virological, biochemical and histological responses, with delayed and infrequent development of resistance.44 Hadziyannis et al45 reported 4‐year and 5‐year data from a long‐term study of adefovir 10 mg daily in patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB. Seventy patients were followed up through 5 years. After 5 years of treatment, the proportion of patients with ⩾1‐point decrease in Ishak fibrosis increased to 71% (p = 0.005), whereas the proportion of patients with HBV DNA <1000 copies/ml reached 67% and ALT normalisation was achieved in 69%. The cumulative probability of acquiring adefovir resistance (A181V or N237T) reached 28%. Four patients had a verified increase in serum creatinine levels.

The point worth noting is that the onset of adefovir resistance was delayed in adefovir‐treated patients, but by year 5, resistance had developed in 28% of patients. There also seemed to be a plateau in the percentage of patients with undetectable HBV DNA and normalisation of serum ALT by year 5. This supports previous findings that there is a proportion of patients with HBV who have a poor response to adefovir.46 Continued treatment in these patients is unlikely to produce any additional benefit and carries the risk of emerging viral resistance. Two potential options for managing these patients with inadequate response are to switch from adefovir to a different drug or a combination therapy regimen.

Entecavir

Entecavir, a carboxylic analogue of guanosine, has potent and selective inhibitory activity against all HBV polymerase functions.47 Entecavir has demonstrated efficacy against lamivudine‐resistant YMDD mutant HBV strains.48 In a recent large randomised clinical trial of entecavir, at 24 weeks, serum HBV DNA levels were undetectable by the bDNA assay in about 50–75% of patients who were given 0.5 or 1.0 mg entecavir daily. The median serum HBV DNA drop at 24 weeks was log 3.9 and 4.4 for the 0.5‐mg and 1.0‐mg entecavir doses, respectively, whereas a biochemical response was observed in about 60% of patients at 24 weeks.49

In the latest published phase III, double‐blind trial,50 715 treatment‐naive patients with HBeAg‐positive CHB were randomised to receive 0.5 mg of entecavir or 100 mg of lamivudine once daily for a minimum of 52 weeks. The primary efficacy end point was histological improvement (a decrease of at least two points in the Knodell necroinflammatory score, without worsening of fibrosis) at week 48. Secondary end points included a reduction in the serum HBV DNA level, HBeAg loss and seroconversion, and normalisation of the ALT level. Histological improvement after 48 weeks occurred in 72% of patients in the entecavir group compared with 62% in the lamivudine group (p = 0.009). More patients in the entecavir group than in the lamivudine group had undetectable serum HBV DNA levels according to a PCR assay (67% v 36%, p<0.001) and normalisation of ALT levels (68% v 60%, p = 0.02). The mean reduction in serum HBV DNA from baseline to week 48 was greater with entecavir than with lamivudine (log 6.9 v log 5.4 (log to the base 10) copies/ml, p<0.001). HBeAg seroconversion occurred in 21% of entecavir‐treated patients and in 18% of lamivudine‐treated ones (p = 0.33). No viral resistance to entecavir was detected. Safety was similar in the two groups.

Another multicentre randomised trial determined the efficacy of entecavir in 184 patients with lamivudine‐refractory CHB. Complete response (undetectable HBV DNA and normalisation of ALT) occurred in 29% of patients from the 1‐mg entecavir group, 19% from the 0.5‐mg entecavir group and in 4% of patients from the lamivudine group after 48 weeks of treatment.51 In a phase III trial that included 583 HBeAg‐negative, nucleoside‐naive patients, patients were randomised to receive either entecavir 0.5 mg daily or lamivudine 100 mg daily. After 48 weeks of treatment, those receiving entecavir showed greater histological improvement (70% v 61%) and a greater rate of suppression of serum HBV DNA levels to <400 copies/ml (91% v 73%) than those receiving lamivudine. But there was no considerable difference in the rate of ALT normalisation (86% v 81%). The safety of entecavir was comparable to that of lamivudine, and no entecavir resistance was observed.52

The development of entecavir resistance requires pre‐existing lamivudine resistance substitutions. Colonno et al53 reported on the resistance data for entecavir. The 1‐year entecavir data showed no resistance in nucleoside‐naive patients and a resistance of 1% in patients with prior lamivudine resistance. By 2 years of entecavir treatment, 10% of patients with prior lamivudine resistance had developed entecavir resistance. Eighteen patients (of >650 nucleoside‐naïve patients) had virological rebound, defined as a greater than 10‐fold increase in HBV DNA from nadir on entecavir. None of these patients showed evidence of emerging entecavir resistance substitutions. Thus, there was no resistance to entecavir after 2 years of treatment in nucleoside‐naive patients. This study highlights the risk of sequential use of antivirals in treating HBV infection. Therefore, on the basis of these findings, it seems that patients with lamivudine resistance should not be simply switched to entecavir monotherapy.

The improved histological benefit of entecavir as compared with lamivudine and its greater effect on viral suppression suggest that with long‐term treatment, entecavir is likely to reduce the risk of end‐stage liver disease and HCC. As both entecavir and lamivudine have showed the same tolerability profiles in various studies, it is evident that entecavir is well tolerated by patients with CHB. Fewer patients in the entecavir group developed ALT flares during treatment. Considering all the available data, entecavir can be used as the primary monotherapy in patients with treatment‐naive CHB.

Combination therapy of lamivudine and IFN

In patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB, combination therapy has no advantage over monotherapy with lamivudine or IFN.54,55,56,57

Newer therapies for HBeAg‐negative CHB

Clevudine

Yoo et al58,59 reported data from phase III trials of clevudine, an l‐nucleoside, in the treatment of patients with HBeAg‐positive and HBeAg‐negative CHB. In the study on HBeAg‐negative CHB,59 83 patients were assigned to receive either clevudine 30 mg daily or placebo for 24 weeks of treatment, followed by 24 weeks of follow‐up. Table 2 shows the results.

Table 2 Treatment with clevudine in patients with hepatitis B e antigen‐negative chronic hepatitis B.

| Clevudine | Placebo | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 weeks | |||

| Median decrease in HBV DNA (log10 copies/ml) | 4.25 | 0.48 | <0.001 |

| HBV DNA<300 copies/ml (%) | 92.1 | 0 | |

| Normal ALT (%) | 74.6 | 33.3 | |

| 48 weeks (24 weeks post treatment) | |||

| Median decrease in HBV DNA (log10 copies/ml) | 3.11 | 0.66 | <0.001 |

| HBV DNA <300 copies/ml (%) | 16.4 | 0 | |

| Normal ALT (%) | 70.5 | — |

HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

No viral resistance was seen in this study. This study shows that clevudine is a potent inhibitor of HBV in HBeAg‐negative patients.

Telbivudine

Data from the GLOBE study60 (table 3), a phase III randomised, blinded 2‐year trial of telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with CHB (n = 1367), have been recently reported. In this study, 84% of patients receiving telbivudine became PCR negative compared with 67% from the lamivudine arm (p<0.01) at 76 weeks. There was no primary failure to treatment with telbivudine. Primary treatment failure was defined as an HBV DNA never <5 log10 copies/ml. Telbivudine had greater potency than lamivudine and is likely to be approved in the near future. How telbivudine fits into the armamentarium of treatment for CHB remains to be determined.

Table 3 Comparison of telbivudine and lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| HBeAg negative | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Telbivudine | Lamivudine | p Value | |

| 52 weeks | |||

| PCR negative (%) | 88 | 71 | <0.01 |

| HBeAg loss (%) | |||

| HBeAg seroconversion (%) | |||

| Resistance | 2 | 7 | <0.01 |

| Primary treatment failure (%) | 0 | 3 | |

| 76 weeks | |||

| PCR negative (%) | 84 | 67 | <0.05 |

| HBeAg seroconversion (%) | |||

HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Therapies on the horizon

Tenofovir

Tenofovir, similar to adefovir, a nucleotide analogue, is used in the treatment of HIV infection. It also has a potent anti‐HBV activity. A recently published study suggested that tenofovir may be a more potent agent than adefovir.46 van Bommel et al61 prospectively studied the effectiveness of tenofovir and adefovir in patients with lamivudine resistance. Table 4 shows the results. The presence of mutations associated with lamivudine resistance at baseline was associated with a lower rate of viral suppression at 12 and 18 months in the adefovir group only.

Table 4 Comparison of treatment with adefovir and tenofovir in patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| Adefovir n = 53 | Tenofovir n = 35 | |

|---|---|---|

| HBV DNA <400 copies/ml | ||

| 12 months | 32 | 94 |

| 18 months | 35 | 100 |

| 24 months | 49 | 100 |

| Viral resistance (%) | 3.7 | 0 |

| HBeAg loss (%) | 21 | 51 |

| HBsAg loss (%) | 6 | 12 |

HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

In a multicentre analysis, Mauss et al62 compared patients with HBV/HIV coinfection receiving an antiretroviral regimen including tenofovir and lamivudine with those who had highly replicative lamivudine‐resistant hepatitis B, receiving tenofovir monotherapy only. No resistance to tenofovir was observed. Tenofovir was very effective in the coinfected patients with or without lamivudine resistance, and tenofovir monotherapy seemed to be as effective as combination therapy with tenofovir and lamivudine (sustained undetectable HBV DNA at 24 months <1000 copies/ml, 83%; HBeAg loss, 25%). The studies discussed above make it evident that tenofovir has potentially greater antiviral activity than adefovir. Tenofovir also seems to be more effective than adefovir in avoiding the development of drug resistance. No study is yet available on the role of tenofovir in patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB.

Current treatment recommendations

There exists no confusion about the fact that patients with raised aminotransferase levels, raised serum HBV DNA levels and active histology need treatment irrespective of their HBeAg status. The question that remains unanswered is what needs to be done with patients with normal serum aminotransferase levels. Published guidelines by various organisations on the management of patients with CHB have not recommended treating patients with normal serum aminotransferases unless a liver biopsy shows major disease activity.62,63,64,65 In this review, we have discussed this dilemma only in HBeAg‐negative patients. The clinician needs to differentiate between the patient who is an inactive carrier (typical presentation: older age, normal serum ALT, HBeAg negative, low HBV DNA levels (<104 copies/ml) and histology showing no inflammation but varying amounts of fibrosis) and the patient who has HBeAg‐negative CHB (typical presentation: older age, raised serum ALT, HBeAg negative, raised HBV DNA (typically >104 copies/ml) with active inflammation). The first group of patients does not need immediate treatment, but the second group does (table 5).

Table 5 Current treatment recommendations for patients with hepatitis B e antigen‐negative chronic hepatitis B10.

| HBV DNA (copies/ml) | Alanine aminotransferase | Treatment strategy |

|---|---|---|

| <104 | Normal | No treatment |

| Monitor every 6–12 months | ||

| Consider treatment in patients with known major histological disease, even if low levels of replication | ||

| ⩾104 | Normal | Low efficacy for lamivudine, interferon, adefovir or entecavir |

| Consider biopsy, and treat if disease activity present | ||

| ⩾104 | Raised | Adefovir, lamivudine, entecavir, PEGylated interferon, or interferon are preferred options |

| Long‐term treatment required: adefovir or entecavir preferred |

Three recent studies throw light on this issue. Wang et al66 looked specifically at patients with a normal serum ALT level on at least two occasions in the 2 years before their liver biopsy. The median HBV DNA level was 5.1×107 copies/ml. Among the 13 patients studied, 10 had increased fibrosis on liver biopsy. In another retrospective study by Nguyen et al,67 patients with an HBV DNA level >10 000 copies/ml and normal or minimally raised serum ALT level were evaluated by liver biopsy. They identified 39 patients with persistently normal ALT levels and 17 with serum ALT 1–2 times the upper limit of normal. In all, 60% of patients were HBeAg negative, 43% had an HBV DNA >6 log10 copies/ml; 12% of patients with a persistently normal serum ALT level had major histology, defined as grade 2, stage 2 or higher. Multivariate analysis showed that only age >45 years was an independent predictor of relevant histology. Thus a normal ALT level in patients with CHB does not necessarily correlate with inactive histology. For HBeAg‐negative patients with normal ALT, the effort should focus on differentiating between the inactive carriers and those with HBeAg‐negative CHB. A helpful clue is the serum HBV DNA level, with inactive carriers having lower levels of viraemia (<104 copies/ml) and those with HBeAg‐negative CHB typically having HBV DNA levels >104 copies/ml. There is, however, no absolute level of HBV DNA that correlates with active histology, and the clinician should maintain a low threshold for performing a biopsy if there is any uncertainty regarding appropriate categorisation of the patient. For patients with HBV DNA level <104 copies/ml and normal ALT levels, no treatment is required. These patients should be monitored at 6–12‐monthly interval for any increase in ALT levels. There should be a low threshold for performing a liver biopsy, and if major disease is present, treatment should be initiated. For patients with HBV DNA level >104 copies/ml and normal ALT levels, liver biopsy should be performed and treatment started if considerable activity is present. Unfortunately, the efficacy for lamivudine, IFN, adefovir or entecavir in this group of patients is low. For patients with HBV DNA level >104 copies/ml and raised ALT levels, adefovir, lamivudine, entecavir, PEG‐IFN or IFN are the preferred options. If long‐term treatment is required then adefovir or entecavir are preferred, as lamivudine has a high rate of development of resistant mutants.

Recommended dose regimens63

IFNα is given as subcutaneous injections

For adults, 5 million units daily or 10 million units three times weekly

For children, 6 million units/m2 three times weekly, with a maximum of 10 million units

Duration of treatment is 12 months.

Lamivudine is given orally

For adults with normal renal functions and no HIV infection, the dose is 100 mg daily

For children, the dose is 3 mg/kg/day, with a maximum of 100 mg/day.

Recommended treatment duration for HBeAg‐negative CHB is longer than 1 year, but the optimum duration is not established

For patients with HIV infection, the dose is 150 mg daily, with other antiretrovirals.

Adefovir is given orally

Recommended dose is 10 mg/day, with normal renal function

Duration of treatment is longer than 1 year, but optimum duration is not established

The recommended duration for patients with lamivudine‐resistant mutants has not yet been determined.

Conclusion

HBeAg‐negative CHB is a potentially severe disease that rapidly progress to cirrhosis and related complications. Although treatment is available, sustained virological and biochemical response is poor after the recommended duration of treatment. Prolonging the duration of treatment may help to attain sustained response, but emergence of resistant strains cautions against prolonged treatment, especially with lamivudine. Entecavir or adefovir can be used as the preferred oral treatment in nucleoside‐naive patients. In lamivudine‐resistant patients, adding entecavir may be superior to adding adefovir, as the chances of developing drug resistance is less for entecavir compared with that for adefovir. As data on newer drugs and more data on available drugs emerge, there might be a possibility of consensus development on the management of patients with HBeAg‐negative CHB.

Abbreviations

ALT - alanine aminotransferase

CHB - chronic hepatitis B

ETR - end‐of‐treatment response

HBeAg - hepatitis B e antigen

HBsAg - hepatitis B surface antigen

HBV - hepatitis B virus

HCC - hepatocellular carcinoma

IFN - interferon

PCR - polymerase chain reaction

PEG‐IFN - polyethylene glycol moiety attached to interferon

YMDD - tyrosine methionine d‐aspartate d‐aspartate

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mast E E, Alter M J, Margolis H S. Strategies to prevent and control hepatitis B and C virus infections: a global perspective. Vaccine 1999171730–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McQuillan G M, Coleman P J, Kruszon‐Moran D.et al Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1976 through 1994. Am J Public Health 19998914–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jongh F E, Janssen H L, de Man R A.et al Survival and prognostic indicators in hepatitis B surface antigen‐positive cirrhosis of the liver. Gastroenterology 19921031630–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fattovich G, Giustina G, Schalm S W.et al Occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and decompensation in Western European patients with cirrhosis type B. Hepatology 19952177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merican I, Guan R, Amarapuka D.et al Chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Asian countries. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 200015135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bortolotti F, Cadrobbi P, Crivellaro C.et al Long‐term outcome of chronic type B hepatitis in patients who acquire hepatitis B virus infection in childhood. Gastroenterology 199099805–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funk M L, Rosenberg D M, Lok A S F. World‐wide epidemiology of HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B and associated pre‐core and core promoter variants. J Viral Hepat 2002952–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keefe E, Dieterich D, Steve‐Huy B. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004287–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papatheodoridis G V, Manesis E, Hadziyannis S J.et al The long‐term outcome of interferon‐alpha treated and untreated patients with HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 200134306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadziyannis S J, Vassilopoulos D. Hepatitis B e antigen‐negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 200134617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu C J, Hussain M, Lok A S. Quantitative serum HBV DNA levels during different stages of chronic hepatitis B infection. Hepatology 2002361408–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manesis E K, Hadziyannis S J. Interferon alpha treatment and retreatment of hepatitis B e antigen‐negative chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 2001121101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lok A S, Heathcote E J, Hoofnagle J H. Management of hepatitis B 2000. Summary of a workshop. Gastroenterology 20011201828–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lok A S, Wu P C, Lai C L.et al A controlled trial of interferon with or without prednisone priming for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 19921022091–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fattovich G, Farci P, Rugge M.et al A randomized controlled trial of lymphoblastoid interferon‐alpha in patients with chronic hepatitis B lacking HBeAg. Hepatology. 1992 Apr 15584–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadziyannis S, Bramou T, Makris A.et al Interferon alfa‐2b treatment of HBeAg negative/serum HBVDNA positive chronic active hepatitis type B. J Hepatol 199011(Suppl 1)S133–S136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lampertico P, Del Ninno E, Manzin A.et al A Randomized controlled trial of a 24 months course of interferon alfa 2b in patients with chronic hepatitis B who had Hepatitis B who had HBV DNA without hepatitis B e antigen in serum. Hepatology 1997261621–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pastore G, Santantonio T, Milella M.et al Anti‐HBe‐positive chronic hepatitis B with HBV‐DNA in the serum response to a 6‐month course of lymphoblastoid interferon. J Hepatol 199214221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunetto M R, Oliveri F, Coco B.et al Outcome of anti‐HBe positive chronic hepatitis B in alpha‐interferon treated and untreated patients: a long term cohort study. J Hepatol 200236263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papatheodoridis G V, Petraki K, Cholongitas E.et al Impact of interferon‐alpha therapy on liver fibrosis progression in patients with HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat 200512199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papatheodiridis G V, Petraki K, Cholongital E.et al Impact of interferon‐α therapy on liver fibrosis progression in patients with HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis. B J Viral Hepat 200512119–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manesis E K, Hadziyannis S J. Interferon α treatment and retreatment of HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 2001121101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooksley W G, Piratvisuth T, Lee S D.et al Peginterferon alpha‐2a(40 kDa): an advance in the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen positive chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat 200310298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcellin P, Lau G K, Bonino F.et al Peginterferon α‐2a HBeAg‐Negative Chronic Hepatitis B Study Group. Peginterferon α‐2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 20043511206–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcellin P, Lau G K K, Bonino F.et al Sustained response to peginterferon α‐2a (40 KD) (Pegasys) in HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B. 1‐year follow‐up data from a large, randomised multinational study [A512]. J Hepatol 200542(Suppl 2)185–186. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai C L, Chien R N, Leung N W.et al One‐year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. N Engl J Med 199833961–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dienstag J L, Schiff E R, Wright T L.et al Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med 19993411256–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaun R, Lai C L, Liaw Y F.et al Efficacy and safety of 5 years lamivudine treatment of Chinese patients with CHB. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 200116(Suppl)A60–A61. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tassopoulos N C, Volpes R, Pastore G.et al Efficacy of lamivudine in patients with hepatitis B e antigen‐negative/hepatitis B virus DNA‐positive (precore mutant) chronic hepatitis B. Lamivudine Precore Mutant Study Group. Hepatology 199929889–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y H, Wu J C, Chang T ‐ T.et al Analysis of clinical, biochemical and viral factors associated with early relapse after lamivudine treatment for HBeAg‐negative CHB in Taiwan. J Viral Hepat 200310277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santantonio T, Mazzola M, Iacovazzi T.et al Long‐term follow‐up of patients with anti‐HBe/HBV DNA‐positive chronic hepatitis B treated for 12 months with lamivudine. J Hepatol 200032300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadziyannis S J, Papatheodoridis G V, Dimou E.et al Efficacy of long‐term lamivudine monotherapy in patients with hepatitis B e antigen‐negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 200032847–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rizzetto M, Volpes R, Smedile A. Response of pre‐core mutant chronic hepatitis B infection to lamivudine. J Med Virol 200061398–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tassopoulos N C, Volpes R, Pastore G.et al Post lamivudine treatment follow‐up of patients with HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B [abstract]. J Hepatol 199930(Suppl 1)117 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papatheoridis G V, Dimou E, Laras A.et al Course of virologic breakthroughs under long‐term lamivudine in HBeAg‐negative precore mutant HBV liver disease. Hepatology 200236219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manolakopoulos S, Karatapanis S, Elefsiniotis J.et al Clinical course of lamivudine monotherapy in patients with decompensated cirrhosis due to HBeAg negative chronic HBV infection. Am J Gastroenterol 20049957–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikolaidis N, Vassiliadis T, Giouleme O.et al Effect of lamivudine treatment in patients with decompensated cirrhosis due to anti‐HBe positive/HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B. Clin Transplant 200519321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida E M, Ramji A, Chatur N.et al Regression of cirrhosis associated with hepatitis B e antigen‐negative chronic hepatitis B infection with prolonged lamivudine therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16;355–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Marcellin P, Chang T T, Lim S G.et al Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B antigen‐positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2003348808–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadziyannis S J, Tassopoulos N C, Heathcote E J.et al Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B antigen‐negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2003800–807. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Knight W, Hayashi S, Benhamou Y.et al Dosing guidelines for adefovir dipivoxil in the treatment of HBV infected patients with renal or hepatic impairment. J Hepatol 200236(Suppl 1)136 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heathcote E, Jeffers L, Perrillo R.et al Sustained antiviral response and lack of viral resistance with long term adefovir dipivoxil therapy in chronic HBV infection. J Hepatol 200236(Suppl 1)110 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hadziyannis S, Tassopoulos N, Heathcote E.et al Two year results from a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled study of adefovir dipivoxil for presumed precore mutant chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 200338(Suppl 2)143 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hadziyannis S J, Tassopoulos N C, Heathcote E J.et al Adefovir dipivoxil 438 Study Group. Long‐term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 20053522673–2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hadziyannis S, Tassopoulos N C, Chang T T.et al Long‐term adefovir dipivoxil treatment induces regression of liver fibrosis in patients with HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B: results after 5 years of therapy [abstract]. Hepatology 200542754A [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Bommel F, Wunsche T, Mauss S.et al Comparison of adefovir and tenofovir in the treatment of lamivudine‐resistant hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 2004401421–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamanaka G, Wilson T, Innaimo S.et al Metabolic studies on BMS‐200475, a new antiviral compound active against hepatitis B virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 199943190–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Man R, Wolters L, Nevens F.et al A study of oral entecavir given for 28 days in both treatment‐naive and pre‐treated subjects with chronic hepatitis [abstract]. Hepatology 200032376A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tassopoulos N, Hadziyannis S, Cianciara J.et al Entecavir is effective in treating patients with chronic hepatitis B who have failed lamivudine therapy [abstract]. Hepatology 200134340A [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang T T, Gish R G, de Man R.et al A Comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg‐positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 20063541001–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang T T, Gish R G, Hadziyannis S J.et al BEHoLD Study Group. A dose‐ranging study of the efficacy and tolerability of entecavir in Lamivudine‐refractory chronic hepatitis B patients. Gastroenterology 20051291198–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheinquer H, shouval D, Lai C L.et al Entecavir demonstrate superior histological and virologic efficacy over lamivudine in nucleoside‐naive HbeAg‐ve chronic hepatitis B. Results of Phase III trial ETV‐027. Hepatology 200440728A [Google Scholar]

- 53.Colonno R, Rose R, Levine S.et al Entecavir two year resistance update: no resistance observed in nucleoside naive patients and low frequency resistance emergence in lamivudine refractory patients [abstract]. Hepatology 200542573A [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oguz K, Ali T, Mustafa T.et al Effectiveness of lamivudine and interferon‐alpha combination therapy versus interferon‐alpha monotherapy for the treatment of HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B patients: a randomized clinical trial. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 200538262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karabay O, Tamer A, Tahtaci M.et al Effectiveness of lamivudine and interferon‐alpha combination therapy versus interferon‐alpha monotherapy for the treatment of HBeAg‐negative chronic hepatitis B patients: a randomized clinical trial. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 200538262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Economou M, Manolakopoulos S, Trikalinos T A.et al Interferon‐alpha plus lamivudine vs lamivudine reduces breakthroughs, but does not affect sustained response in HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol 2005115882–5887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manesis E K, Papatheodoridis G V, Hadziyannis S J. A partially overlapping treatment course with lamivudine and interferon in hepatitis B e antigen‐negative chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 20062399–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoo B C, Kim J H, Lee K S.et al A 24‐week clevudine monotherapy produced profound on‐treatment viral suppression as well as sustained viral suppression and normalization of aminotransferase levels for 24 weeks off‐treatment in HBeAg(+) chronic hepatitis B patients [abstract]. Hepatology 200542270A [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoo B C, Chung Y H, Han B H.et al Clevudine is highly efficacious in HBeAg chronic hepatitis B patients with a sustained antiviral effect after cessation of therapy [abstract]. Hepatology 200542268A [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lai C L, Gane E, Liaw Y F.et al Telbivudine vs lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B: first‐year results from the International Phase III GLOBE Trial [abstract]. Hepatology 200542748A [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Bommel F, Mauss S, Zollner B.et al Long‐term effect of tenofovir in the treatment of lamivudine‐resistant hepatitis B virus infections in comparison to adefovir [abstract]. Hepatology 200542269A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mauss S, Nelson M, Lutz T.et al First line combination therapy of chronic hepatitis B with tenofovir plus lamivudine versus sequential therapy with tenofovir monotherapy after lamivudine failure [abstract]. Hepatology 200542574A [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lok A S, McMohan B J. Practice Guidelines Committee, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Chronic hepatitis B: update of recommendations, Hepatology 200439857–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Franchis R, Hadengue A, Lau G.et al EASL International Consensus Conference on hepatitis B. J Hepatol 200339(Suppl 1)S3–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liaw Y F, Leung N, Guan R.et al Asian‐Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: an update. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 200318239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang C, Deubner H, Shuhart M.et al High prevalence of significant fibrosis in patients with immunotolerance to chronic hepatitis B infection [abstract]. Hepatology 200542573A [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nguyen M, Trinh H, Garcia R T.et al Significant histologic disease in HBV‐infected patients with normal to minimally elevated ALT levels at initial evaluation [abstract]. Hepatology 200542593A [Google Scholar]