Abstract

Deoxyribonuclease II (DNase II) is an endonuclease with optimal activity at low pH, localized within the lysosomes of higher eukaryotes. The origin of this enzyme remains in dispute, and its phylogenetic distribution leaves many questions about its subsequent evolutionary history open. Earlier studies have documented its presence in various metazoans, as well as in Dictyostelium, Trichomonas and, anomalously, a single genus of bacteria (Burkholderia). This study makes use of searches of the genomes of various organisms against known DNase II query sequences, in order to determine the likely point of origin of this enzyme among cellular life forms. Its complete absence from any other bacteria makes prokaryotic origin unlikely. Convincing evidence exists for DNase II homologs in Alveolates such as Paramecium, Heterokonts such as diatoms and water molds, and even tentative matches in green algae. Apparent absences include red algae, plants, fungi, and a number of parasitic organisms. Based on this phylogenetic distribution and hypotheses of eukaryotic relationships, the most probable explanation is that DNase II has been subject to multiple losses. The point of origin is debatable, though its presence in Trichomonas and perhaps in other evolutionarily basal “Excavate” protists such as Reclinomonas, strongly support the hypothesis that DNase II arose as a plesiomorphic trait in eukaryotes. It probably evolved together with phagocytosis, specifically to facilitate DNA degradation and bacteriotrophy. The various absences in many eukaryotic lineages are accounted for by loss of phagotrophic function in intracellular parasites, in obligate autotrophs, and in saprophytes.

Keywords: Deoxyribonuclease II, Eukaryotes, Protists, Algae, Phagotrophy

1. Introduction

Deoxyribonucleases (DNases) are general, non-sequence specific endonucleases that degrade DNA molecules. DNase II was found to be widely distributed in mammalian tissues (Cordonnier and Bernardi, 1968). The enzyme belongs to the group of acid DNases whose optimal activity occurs at low pH (4.5–5.5). Among its other characteristic biochemical properties are inhibition of its activity in the presence of cations, specifically Zn2+, and a characteristic digest pattern that produces DNA fragments, generating 3′ phosphate and 5′ OH (hydroxyl) ends by breaking the phosphodiester bond between nucleotides in the chain (Evans and Aguilera, 2000).

In mammalian cells, DNase II is known to be active in lysosomes, where it plays a particularly important role in the immune function of phagocytosis, as well as in engulfment-mediated DNA degradation during development. Both the amino acid sequence of the entire molecule and of the conserved catalytic domain have been identified and structurally characterized (Evans and Aguilera, 2000).

Since its discovery in mammalian cells, DNase II and closely related enzymes have been documented to occur in a variety of metazoa, including Drosophila and Caenorhabditis (Krieser and Eastman, 2000), as well as having been found in flatworms (Schistosoma), echinoderms (Acanthaster, Strongylocentrotus), and in all vertebrates analyzed from which the complete genome is known (Danio, Fugu, Xenopus, Gallus, Mus, Homo, etc.). DNase II has been found to perform a variety of functions in these organisms, from digestion of ingested bacterial DNA to more specialized roles in the toxin of the Crown of Thorns sea star Acanthaster (Evans and Aguilera, 2000), as well as preliminary evidence for its presence in the venoms of rattlesnakes (Aguilera et al., unpublished).

As another example of its varied functions, in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, DNase II has been shown to be required for the removal of DNA after engulfment and bacterial DNA from the gut lumen (Lyon et al., 2000). In DNase II deficient nematodes, phagocytic cells retain condensed masses of apoptotic-cell DNA and large quantities of undigested bacterial DNA in the gut (Lyon et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2000).

In addition, our group has recently demonstrated that depletion of DNase II in Drosophila melanogaster results in severe immunodeficiency after bacterial infection via septic injury (Seong et al., 2006). This immunodeficiency was likely mediated by disruption of phagocyte function as the number of these cells was found to be significantly reduced in DNase II deficient flies.

Evidence indicating the important role of DNase II in “higher” animals was subsequently observed in transgenic mice that were defective for Caspase Activated DNase (CAD), a nuclease activated during apoptosis (Liu et al., 1997). It was demonstrated that apoptotic cells in these mice exhibited little or no DNA fragmentation, yet these mice appeared to be normal, without the accumulation of apoptotic cellular DNA. These results suggested that the pre-fragmentation of apoptotic-cell DNA was not essential for complete degradation of DNA as this process could still take place within phagocytes through the action of DNase II.

The importance of mammalian DNase II was further demonstrated by targeted gene disruption in mice (Kawane et al., 2001). Mutation of this gene was found to result in perinatal lethality due to altered macrophage function and definitive erythropoiesis (Kawane et al., 2001; Krieser et al., 2002). DNase II-null macrophages were found to contain many undegraded nuclei, which apparently compromised their phagocytotic and signaling functions. The inability of phagocytes to degrade DNA was evident in the fetal liver, indicating that DNase II enzymes were required for engulfment-mediated DNA degradation (Krieser et al., 2002). It was subsequently demonstrated that adult DNase II-deficient mice succumb to chronic polyarthritis (Kawane et al., 2006). Although no human diseases have been linked to a deficiency in this enzyme, human DNase II polymorphisms have been associated with increased risk of renal disorder among systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients (Shin et al., 2005).

Apart from its role in DNA degradation during the process of phagocytosis, DNase II has also been shown to serve as an effective barrier against the uptake of foreign DNA, which may confer protection against oncogenes and viruses (Howell et al., 2003). It is therefore clear that DNase II serves an essential function in the degradation of ingested DNA and that interference with this function results in severe consequences from embryonic lethality to impaired immunity.

DNase II appears to have undergone gene duplication events since its origin. An acid endonuclease known as DNase IIβ (or as DNase II-like acid DNase, or DLAD), originally described in mammalian cells but apparently widely distributed among vertebrates, has been found to be more tissue specific than DNase II. Along similar lines, there appears to be a large family of DNase paralogs in the parasitic nematode Trichinella (MacLea et al., 2003), suggesting several gene duplication events in these worms. These paralogs are expressed in different phases of the life cycle (hatchling or larval specific) and appear to play a role in the apoptotic processes accompanying metamorphosis.

However, the distribution of DNase II and its paralogs leaves many questions about its origin and subsequent evolutionary history unclear. The gene appears to be ubiquitous in the metazoa, although confirmation of its presence in primitive taxa such as cnidarians and sponges is required (see below). Recent work has documented the presence of the enzyme in the slime mold Dictyostelium (MacLea et al., 2003). While the phylogenetic affinities of slime molds and other “Amoebozoans” are still being debated, rDNA sequence data suggests close affinities with the fungi and metazoan clades (e.g. Bapteste et al., 2002). This, together with the ubiquity of the gene in metazoa, suggests that the origin of DNase II at least predates the metazoa.

More problematic, however, is the discovery of DNase II in a number of other protists, combined with its apparent absence in their close relatives. MacLea et al. (2003) have found homologous sequences in Trichomonas, which, along with the closely related Diplomonads, are thought by many to be among the most evolutionarily basal eukaryotes (Sogin 1991, 1997). In view of the apparent absence of DNase II in most non-metazoan eukaryotes with sequences available on GenBank (e.g. Entamoeba, Plasmodium, Trypanosoma, Giardia), accounting for the occurrence of this enzyme in the eukaryota remains an unresolved issue. Also curious is the presence of DNase II in a single species of bacteria—the Pseudomonad Burkholderia (MacLea et al., 2003). Apart from this instance, DNase II appears to be entirely absent in other Eubacteria and in the Archaea, which are likely to be more closely allied to the eukaryotes (Woese, 1998).

The questions raised by these findings require a detailed phylogenetic analysis so that the issue of DNase II’s origins may have some hope of resolution. The first step in the analysis requires that the distribution of DNase II among a variety of eukaryotic taxa be established, so that as many protists from disparate clades are assayed for the presence or absence of the homologous gene. The presence or absence of the gene can then be mapped onto existing phylogenies of the eukaryota to evaluate competing hypotheses of independent origins and losses from the perspective of parsimony (minimizing the number of independent losses and origins posited ad hoc).

This approach is limited in part by the availability of complete sequence data from relevant groups of organisms, as the genomics of many protist groups has only recently begun to be investigated. In such cases, the presence of the gene can be inferred through experimental assays for acid nuclease activity, although the potential for false positives is quite high. To date, assays for acid nuclease activity have given positive results in a fungus Cordyceps (Ye et al. (2003)), the angiosperm plant Hordeum (Muramoto et al., 1999), and in Euglena, a basal protist (Ikeda and Takata, 2002). However, in some of these cases, such as in Hordeum, the nuclease activity is Zinc-mediated and consequently almost certainly not due to DNase II. It is possible that these organisms have other acid nucleases, or nucleases optimal at neutral pH with residual activity at low pH. Therefore, sequence data is critical to determine presence or absence of the correct nuclease.

The basic questions to be addressed in this study through database searches and the mapping of positive and negative results onto eukaryote phylogenies are the following:

Metazoa. Can it be unequivocally confirmed that DNase II is plesiomorphic (primitive) in the metazoa? While its presence in various protists certainly suggests that this is the case, if independent origin is not ruled out, it is vital to confirm that it indeed occurs in basal animals such as sponges.

Higher eukaryotes. Given its occurrence in the metazoa and amoeboid protists, can its presence or absence be confirmed in other “crown” eukaryotes, such as the red algae, the green algae and true plants, and in fungi? Some tentative evidence based on activity assays suggests presence of the enzyme in such taxa, but these findings must be confirmed with sequence data to eliminate the possibility that enzymes other than DNase II are involved.

Lower eukaryotes. While its presence in a single bacterial genus is almost certainly the result of horizontal transfer, the occurrence of DNase homologs in Trichomonas may suggest primitive origin in the eukaryotic cell. To test this hypothesis, it is necessary to search for homologs in other stem protist groups such as the Metamonads (e.g. Giardia and related organisms), as well as Euglenozoans (both parasitic Apicomplexans and free-living Euglena). Some preliminary sequence data is also available for the phylogenetically problematic “Jakobid” Reclinomonas, which, according to different authors, may either be a close ally of the Euglenozoans (Simpson et al., 2005), or else an evolutionarily basal outgroup to all other eukaryotes, including Metamonads and Euglenozoa (Stiller and Hall, 1999).

Heterokonts and Alveolates. If DNase II is found to be absent in other basal protists, it is important to establish its presence or absence in taxa that are in some way intermediate between the stem Excavate taxa and the other “crown” taxa such as higher plants. Thus, it will be critical to determine their presence or absence in clades such as the Heterokonts (Stramenopiles) and Alveolates (the latter include ciliates and related organisms).

In doing so, a number of widely conflicting phylogenies of the eukaryotes have been consulted. This is done because in this paper, no particular interpretation of eukaryotic phylogeny is argued for, and therefore the evolutionary history of DNase II must be investigated in the light of conflicting claims for the structure of the eukaryotic “species tree”.

In broad terms, there are two competing hypotheses concerning eukaryote evolution. One paradigm, promoted by Cavalier-Smith and colleagues (Cavalier-Smitth, 2002; Cavalier-Smith and Chao, 2006, see also Patterson, 1999), is that the eukaryotes consist of two divergent clades: the unikonts (Amoebozoa, Fungi, and Metazoa) and the bikonts (Metamonads, Euglenozoans, Alveolates, Heterokonts, and plants). This interpretation of eukaryote evolution has been based largely on cell morphology and the presence or absence of characteristic pigments and metabolic pathways, although a similar interpretation based on a number of conservative protein sequences was supported by Simpson et al. (2005). A simplified version of the Cavalier-Smith phylogeny (using the taxa with sequence data as representatives of the major clades), is given in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

Phylogeny of DNase II based on distinct models and interpretations. (A) A simplified phylogeny (“species tree”) of the eukaryota, based largely on the interpretation of Cavalier-Smitth (2002, etc.) where the phylogeny is divided between the bikont clades (Excavates, Alveolates, Heterokonts, Plants) and unikont clades (Amoebozoa, Fungi, Animals). Only taxa represented in the sequence assays are shown in the cladogram. If DNase II is uniquivocably present, the clade is shaded black. If the evidence is equivocal due to lack of data or ambiguous results of BLAST searches, the taxa are shaded in grey, while white shading implies unequivocal absence. The internal branches are shaded in such a way consistent with a unique origin for DNase II. (B) A simplified phylogeny based largely on the interpretation of Bapteste et al. (2002). In this view, the Excavates are a stem outgroup to both the clades Cavalier-Smith classifies as “unikonts” and those that he classifies as “bikonts”, so that the crown taxa together form a monophyletic clade. The shading here (and in the following figure) has the same meaning as in (A). (C) A phylogeny based largely on the interpretation of Stiller and Hall (1999), Stiller et al. (2004). The phylogeny shares with 1b an interpretation of crown clade monophyly with Exacavates as an outgroup (contra Cavalier-Smith), but differs notably from (B) in the details of crown and stem clade phylogeny alike. Notable differences include the classification of Reclinimonas as an ally of Metamonads rather than Euglenozoans, the primitive status of Entamoeba, the status of other “Amoebozoans” as a sister clade to all crown taxa rather than to fungi and animals, and disputation of the relationship between red and green algae.

Recent molecular phylogenies, based largely on rDNA sequences (Sogin and Silberman, 1998; Bapteste et al., 2002), however, suggest that the eukaryotes form a single lineage, with the Excavate clade (Metamonads, Euglenozoan) being basal with respect to all other clades. The next branches, in simplified terms, are the Alveolate and Heterokont clades, followed by the red algae and true plants. The key difference between these interpretations and Cavalier-Smith’s is that most of the multicellular crown taxa form a monophyletic clade, with Excavates as an outgroup, as shown in Fig. 1B.

A number of recent studies incorporating a number of additional sequences and correcting for artifacts such as long branch attraction (Stiller and Hall, 1999; Stiller et al., 2004; Stiller and Harrell, 2005), dispute a number of the details of Fig. 1B. In particular, they place Entamoeba and some other parasitic “Amoebozoans” as quite basal rather than as specialized crown taxa. Furthermore, free-living Amoebozoans such as Dictyostelium form an outgroup to the remaining crown taxa rather than a sister clade to the Ophistokonta. Stiller and Hall also reject a close relationship between the Alveolata and Heterokonta. A simplified account of their interpretation is shown in Fig. 1C.

Alternative hypotheses for the point of origin and subsequent losses of DNase II will be evaluated under these competing models of phylogeny. For many of the crown taxa at least, the precise topological position of any individual clade (e.g. the relationship between Alveolates and Heterokonts) should not significantly alter the interpretation. However, the phylogenetic position of certain taxa as crown versus stem clades, and particularly whether crown taxa form a monophyletic group or not, may ultimately dictate which models for origin and losses are plausible.

It will be argued that the origin and losses of DNase II may be related with the origin and multiple losses of phagotrophic feeding in a number of eukaryotic lineages. While phagotrophy is thought to be a primitive eukaryotic trait, phagotrophic function has been lost in a number of eukaryotes, most obviously in autotrophs such as a variety of “algae” and higher plants, but also in a number of specialized parasite lineages.

The other component of this study entails constructing phylogenies of the DNase II sequences themselves. Once paralogous sequences such as DNase IIβ and the Trichinella duplicates are removed, it is expected that the phylogeny of DNase should give a phylogeny congruent with those obtained for eukaryotes using other sequences (ribosomal RNA genes, etc.). This is stated with the caveat that some discrepancies will no doubt result from the fact that DNase II is subject to its own unique functional and evolutionary constraints and therefore evolves at a different rate from sequences used in phylogenetic analysis.

On the other hand, significant discrepancies between gene trees and species trees could be indicative of horizontal gene transfer. This has been proposed by MacLea et al. (2003) as the most likely explanation for the presence of DNase II in Burkholderia, as the bacterial sequences appears in a subclade with nematode sequences in their analysis. Since Burkholderia is a soil-dwelling bacteria and horizontal gene transfer from eukaryotic cells to bacteria is not uncommon, this probably accounts for the curious occurrence of an otherwise eukaryotic gene in a single bacterial lineage. Below, we will investigate the possibility of similar evolutionary patterns in DNase genes among the lower eukaryotes, as well as more conventional hypotheses of independent origins and losses.

2. Materials and methods

DNase II and its paralogs have been sequenced in a number of organisms, for which the gene (both the coding DNA and translated protein sequences) has been annotated in NCBI GenBank and other public databases.

Representative amino acid sequences of DNase II from mammals (mouse), insects (Drosophila) and nematodes (Caenorhabditis) were used to conduct preliminary BLAST searches (Altschul et al., 1990) against the entire dataset in GenBank. The preliminary searches, unless otherwise indicated, were executed using the default BLAST settings, i.e. a BLOSUM62 amino acid substitution scoring matrix.

These preliminary searches in turn provided matches to sequences from non-metazoan genomes (i.e. from several protists as well as Burkholderia), which could then themselves be used as query sequences against the entire database. Of course, the searches could be restricted to individual species or taxonomic groups as far as availability of genomic information permitted. In most cases, the matches were confirmed using a reverse search, where the BLAST hits themselves were used as query sequences to determine whether the best subsequent hits would be DNase II.

For a number of taxa of interest (various algae, protists, and lower metazoans) genome projects are works in progress. As such, preliminary data is available through Gen-Bank in their trace file archive, in the form of FASTA libraries of DNA sequences. A number of these projects have their preliminary data at locations other than Gen-Bank. Specifically, the sequencing project for the red algae Cyanidioschyzon is being conducted by a Japanese group, with data archives at http://merolae.biol.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Another red algae, Galdiera, has a genome project data archive at http://genomics.msu.edu/galdieria/sequence_data.html. The data sets for Euglena, Reclinomonas, and several other protists, in various stages of completion, can be found at the University of Montreal protist EST project http://megasun.bch.umontreal.ca/pepdb/pep.html. For data sets where only DNA sequences were available, TBLAST (translated search against protein query) was used to find possible homologous matches in these partial genomes, sometimes with mixed results when the sequence data was incomplete or ambiguous. In most cases, a query sequence was chosen from an organism as closely related as possible to the target, for instance, Dictyostelium sequences were used for searching protists.

Because many of the lineages of interest nevertheless shared common ancestors hundreds of millions of years ago, it is likely that sequence divergence may mask information on homology. To determine whether this is the case, both the entire DNase II sequence was used as a query as well as one of the most highly conserved regions of the protein that encompasses the carboxyl-terminal catalytic domain (see Evans and Aguilera, 2000). For example, in Dictyostelium, the downstream catalytic domain sequence (starting at amino acid position 306), with the most conserved residues presented in bold type below:

TKDHSKYALSIHEADYYICIGDVNRMFTQFKRGGGS

An upstream region has also been proposed as part of a catalytic domain. This short region contains a highly conserved “HSK” motif (starting at site 122 in the Dictyostelium sequence, for example).

The validity of matches was confirmed not only through the e-values associated with the searches (as a heuristic, matches with e-values greater than 0.001 were rejected, or at lest treated with skepticism), but also through scores and visual information produced through pairwise alignments with known DNase II query sequences. Pairwise and multiple sequence alignments were performed using Clustal (Thompson et al., 1994) for fast heuristic alignments.

Once a complete set of sequences was obtained, a multiple alignment was performed using ClustalX, again based on a BLOSUM62 scoring matrix. A representative multiple alignment of DNase II sequences (from Dictyostelium, Trichomonas, Paramecium, Caenorhabditis, and Homo) is shown in Fig. 2. The aligned sequences were also analyzed using PHYLIP (Felsenstein, 1989), using the protpars and proml routines for maximum parsimony and maximum likelihood on amino acid sequences (e.g. Felsenstein, 2004). The maximum likelihood calculation assumed the Jones–Taylor–Thornton model of equal substitution rates for all amino acids as a computationally convenient approximation. To determine the extent to which the phylogenies are artifacts of the parameters and assumptions in the algorithm, the likelihood trees were compared to those obtained under different substitution models, and the parsimony trees were compared to those derived under different constraints, such as Dollo Parsimony or asymmetries in the substitution rates. However, because little is known about what substitutions are tolerated in the DNase sequence, the null model for parsimony and transition rates was used for all of the phylogeny reconstructions. Subsequent analysis for robustness of the resulting parsimony and likelihood-based trees was carried out using bootstrap analysis (100 samplings from the sequence data), using the bootseq and consense (for building consensus trees from the bootstrapped data) modules in PHYLIP. Finally, the phylogenies were edited and displayed using MrEnt, a tree editor and visualization package freely available from the Swedish Museum of Natural History (Zuccon and Zuccon, 2006), and Tree-view (Page, 1996).

Fig. 2.

A ClustalX (1.82) based multiple alignment of DNase II amino acid sequences from a number of eukaryotic taxa: Paramecium (a ciliate Alveolate), Dictyostelium (an Amoebozoan), Caenorhabditis (an “ecdysozoan” metazoan) andHomo(a deuterostome metazoan). The close sequence similarity, including a large number of identical shared amino acids, strongly supports common ancestry. The shading in the multiple alignment denotes the degree of match or mismatch, with black representing perfect matches, and grey representing mismatches of closely related amino acids (under aBLOSUM62scoring system). All aligned sequences contain the six predicted amino acids confirming the catalytic domains of the enzyme, as indicated by the black arrow.

3. Results

3.1. Metazoa

As proposed in the introduction, the first search conducted was done to confirm that DNase II is plesiomorphic in the metazoa. Every animal with a completed genome project has given unambiguous hits for DNase II homologs, including deuterostomes (vertebrates, echinoderms), ecdysozoans (nematodes, arthropods), and lophotrochozoan taxa such as flatworms. This strongly supports the view that DNase II is a shared primitive trait of the metazoa.

Sponges (Porifera) are widely considered to be the most primitive living animals (e.g. Valentine (2004)), so the sequence data for Reniera, a Desmosponge with an in-progress genome project, was assayed for DNase II homologs. To date, the sequences are only available as FASTA libraries, so that the search was executed using TBLASTN search against this library, using both Dictyostelium and Caenorhabditis as query sequences. It should be noted that many of the sequences contain large numbers of unresolved nucleotides, which makes searches over certain sections of the genome problematic.

As a result of the query, a match from ORF EMBOSS_001_6 in Reniera was found. The alignment obtained from a TBLASTN search (with the best matches giving a relatively poor e-value of 0.89) of the query against the translated sponge ORF. Supplementary Fig. A.1 shows the output (scores and alignment of matches) of the TBLASTN search.

In spite of the high e-value and the restricted region of alignment, a “reverse” BLAST search of sections of the translated sequence against the general GenBank database, detected among other hits, metazoan DNase II, although the e-values for this reverse search also tended to be high (of order ~0.1 or higher) and there were a number of unrelated protein hits as well.

Given the information available, it cannot be definitely stated that DNase II is present in Reniera, although the overall sequence similarity, particularly in the downstream catalytic domain region, was quite suggestive of homology.

3.2. Fungi, plants, and algae

Although experimental assays suggest acid nuclease activity in plants and fungi, there is no sequence data to support the claim that the activity is due to DNase II rather than some other nuclease. Furthermore, in the case of the barley plant Hordeum where acid nuclease activity was documented by Muramoto and colleagues (1999), the enzyme appears to be Zn2+ dependent rather than inhibited. Complete sequenced and annotated genomes are available at GenBank and elsewhere for the dicot Arabidopsis and monocots Oryza, and Zea (among others in various stages of work), and none of them gave significant sequence alignments against either the complete sequences or the catalytic domains from Dictyostelium or any other DNase II sequence.

In the case of fungi, both complete Ascomycete (Aspergillus, Sacchoromyces, Neurospora) and Basidiomycete (Coprinopsis, Cryptococcus) sequences are available through GenBank, and as with higher plants, there are no significant matches. The few hits that came up at all (with e-values of the order 0.1 or higher) were from obviously non-homologous genes such as the yeast translation initiation factor (data not shown).

The presence of DNase II in animals and a slime mold combined with absence in higher plants and fungi suggests that one investigate their close relatives. The higher plants are closely allied to (and probably evolved from) the chlorophytes (green algae), a number of which have ongoing genome projects. The genome project for Volvox, a colonial Volvocale chlorophyte, has recently been completed and is currently in the annotation phase.

Volvox FASTA libraries searched against a Dictyostelium sequence query revealed a single match (see Supplementary Fig. A.2). The sequences as a whole have limited homologous domains, but the evidence for homologs to the catalytic domain appear strong based on both the alignment itself and its e-value. Indeed, when the translated Volvox sequence was used in a “reverse” search against the GenBank database, all of the highest hits (some with e-values of the order ~10−6) were DNase II sequences.

On the other hand, if one looks at the Rhodophyte algae, which are thought to be close allies of the green algae and plants (see Stiller et al., 2004 for caveats), there is comparatively little support for the presence of DNase II homologs. Based on searches of query sequences on databases maintained for ongoing genome projects for Galdieria and Cyanidioschyzon, no significant matches have been found. For the former, a match with an e-value of 0.71 was obtained, with no correspondence at the catalytic domain, while for the latter, all matches involved very short runs (<10 amino acids) and e-values of 0.49 or greater. The specific sequence matches obtained were the two alignments shown in Supplementary Fig. A.3. While the result from Galdieria are not unequivocally negative, the evidence points very strongly to absence of DNase II homologs in the Rhodophyta.

3.3. Lower eukaryotes: Diplomonads and Euglenozoa

DNase II has been identified in Trichomonas, a primitive protist closely related to Diplomonads such as Giardia. The genome project for the latter organism is complete and available for searches, not one of which yielded any matches to DNase II sequences (or the catalytic domain) from any organism, including its close relative Trichomonas.

Less certain is the status of DNase II in the Euglenozoa, also thought be a stem eukaryotic clade. Homologs are absent in the genomes of Trypanosoma and Leishmannia (parasitic Kinetoplastids). Experimental data suggests the presence of DNase II-like activity in Euglena (Ikeda and Takata, 2002). The evidence from the assay strongly favors the presence of DNase II rather than another nuclease, on the grounds of signature indicators such as cationic inhibition and the presence of characteristic 5′ OH and 3′ PO4 ends typical of this enzyme’s activity (Ikeda and Takata, 2002). Nevertheless, this finding must also be confirmed with sequence data to exclude the possibility that Euglena has some independently derived acid nuclease enzyme.

Genome sequencing of Euglena is still incomplete, but extensive EST libraries are available via the University of Montreal’s Protist genome project website. Based on what sequence data is available, there are no homologous matches to DNase II, apart from some spurious, short runs of sequence from unrelated genes (such as monoglyceride lipase) with very high e-values. Of course, one cannot prove absence from an incomplete genome, as the gene may be present in some yet to be sequenced region, but at this point there is no sequence data to confirm the presence of DNase II in Euglena. On the other hand, there may be a positive match in another stem eukaryote, namely Reclinomonas, whose exact phylogenetic affinities, as mentioned above, are still in dispute.

A search of the Reclinomonas EST database using Dictyostelium DNase II as a query sequence identified regions with high degrees of sequence identity, with e-values of the order ~10−20 (see Supplementary Fig. A.4). The matching sequence also includes the characteristic upstream “HAK” conserved domain (amino acid 445 in the subject sequence), yet there is no match for the downstream catalytic domain region. This is very likely due to this EST being incomplete, as is the case with many EST sequences, and the similarity of the portions of sequence that are present point strongly towards presence in Reclinomonas.

3.4. Alveolates, Heterokonts, and Amoebozoa

Preliminary BLASTP searches of the GenBank database using DNase II query sequences provided two indisputable matches from ciliate protists (Alveolata): Paramecium and Tetrahymena. Not only are the e-values of the order 10−18 for both, but the relationship is visually obvious, as can be seen in Fig. 2. The figure shows an alignment of DNase II homologs from Paramecium against Dictyostelium, Trichomonas, and two representative metazoans (Caenorhabditis and human). Because of its close relationship to Paramecium, sequences from Tetrahymena were not included in the alignment. Curiously, however, Tetrahymena has the longest DNase II sequence among the entire set of assayed taxa.

At present, no Dinoflagellate genomes are available for searching, and DNase II has been found to be absent in Apicomplexans such as Toxoplasma and Plasmodium, in spite of their alleged relationship to the free-living ciliates.

Evidence for the sequence in the “Heterokont” clades (including Diatoms, Phaeophytes, Chrysophytes, and Oomycetes) is somewhat more equivocal. Comparatively few organisms from these groups have any extensive genomic data, so the conclusions reached are based on assays of Phytopthora, an Oomycete, and two diatom species, Thalassiosira and Phaeodactylum. In the case of the oomycete, the case for homology with DNase II sequences is overall fairly strong. A TBLASTN search against a library of Phytophthora nucleotide sequences gave a single match with an e-value of 10−10 (see Supplementary Fig. A.5).

Furthermore, a reverse search using the subject Phytophthora sequence against the GenBank database gave DNase II sequence hits from various organisms as the best matches. However, as was the case with the Reclinomonas hits, the C-terminal catalytic domain in the Dictyostelium did not align with any homologous sequences in the oomycete.

Much the same pattern is observed in TBLASTN searches against a DNA sequence library from the diatom Phaeodactylum, although the e-value was of the order 10−4 and there is a much shorter region of alignment (this time including the first amino acids in the downstream catalytic domain, as can be seen in Supplementary Fig. A.6).

As with the Phytopthora hits, a reverse search using the recovered diatom sequence against the entire BLAST database (using protein–protein searches) detected only known DNase II sequences. The matches for Thalassiosira are similar but involve a somewhat shorter run of amino acids. Altogether, these results suggest that homologs of DNase II may indeed be present in diatoms and oomycetes, perhaps in a divergent form. It would certainly be of interest to obtain sequence data from Chrysophytes and Phaeophytes (golden and brown algae, respectively), but at the moment, none are available.

Finally, while DNase II is present in Dictyostelium, it is thought that that the slime molds are allied to parasitic Amoebozoans such as Entamoeba and free-living forms such as Mastigamoeba. Genomes from the latter two species failed to give any significant matches against Dictyostelium DNase II queries. While the genome project of Mastigamoeba is still an incomplete EST library, allowing for the possibility of missing sequences, the genome of Entamoeba is fully sequenced, translated, and annotated, making the negative result beyond contention.

4. Phylogenetic analysis of DNase II sequences

Fig. 1A–C shows three simplified phylogenetic trees based on competing hypotheses on eukaryotic affinities, with known presence, absence, likely presence, and indeterminate cases marked on the phylogenies. Such character mapping allows one to compare hypotheses of origins and losses.

Phylogenies based on the DNase II sequences themselves offer a more limited perspective on the enzyme’s evolution. While homologous sequence matches have been found in a range of organisms, most of these sequences are incomplete (as in the sponge), or else the homology is over such a limited range of amino acids that multiple alignment of translated ORFs from the diatoms, oomycetes, and algae against complete sequences would not be phylogenetically informative (in part because different stretches of sequences show evidence of homology).

Consequently, the phylogeny of DNase II (the gene tree, as opposed to the hypothesized species trees in Fig. 1A–C) is restricted to complete sequences from the following organisms: Burkholderia, Trichomonas, Tetrahymena, Paramecium, Dictyostelium, Schistosoma, Caenorhabditis, Acanthaster, and Mus. A large number of metazoans have been excluded from the analysis since the status of DNase II in animals is not in question. Also excluded are known paralogs of DNase II, such as mammalian DNase IIβ and the various paralogs discovered in larval Trichinella (MacLea et al., 2003), since their divergence sheds no light on the evolution of the main lineage of DNase.

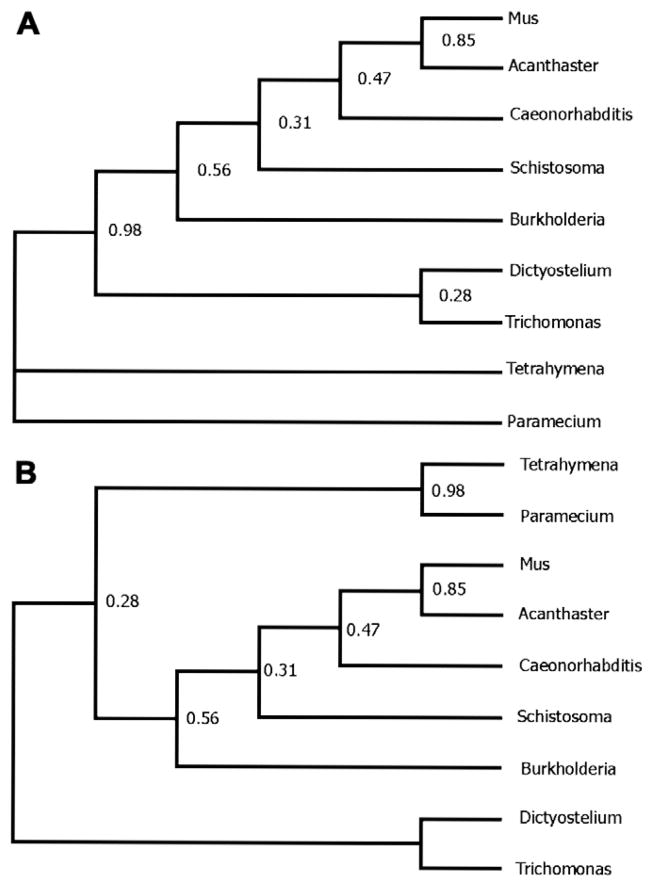

Fig. 3 shows an unrooted maximum likelihood tree, reconstructed under the symmetric Jones–Taylor–Thornton model of amino acid substitution. This is a consensus tree constructed with 100 bootstrap sampling replicates, with the bootstrap values listed at every node. Fig. 4A and B shows the same tree, but rooted with the ciliate taxa and Trichomonas, respectively. The former rooting takes at face value the grouping of Trichomonas DNase II sequence with the crown taxa, while the latter assumes that the gene tree should be congruent with the species tree, in which Trichomonas is the most basal of the Eukaryotes with known DNase II sequence.

Fig. 3.

Unrooted phylogeny (“gene tree”) of DNase II from several organisms: Burkholderia (the only Prokaryote known to have the gene), Trichomonas (an Excavate), (Paramecium, Tetrahymena (both ciliate Alveolates), Dictyostelium (Amoebozoan), and several metazoans. At each node are the bootstrap values supporting each clade. The value of 98 (out of 100) for the ciliates is indicative of their recent divergence and the indisputable homology of the gene. Also fairly well-supported (bootstrap value 56) is the shared homology of DNase II in the metazoa and Burkholderia (a case of lateral transfer). The bootstrap value uniting Dictyostelium and Trichomonas is quite poor. The species tree for these organisms places Trichomonas as an outgroup to all crown eukaryotes, which would imply that the relationship to the Amoebozoa and other crown clades may be spurious.

Fig. 4.

(A) The same phylogeny as in Fig. 3, with Paramecium as the root. (B) As for (A), but with Trichomonas as the root taxon (on the assumption that gene and species trees should be congruent).

Several noteworthy results from the likelihood phylogenies include the fact (first noted in MacLea et al., 2003) that DNase II from the bacterium Burkholderia does not form an outgroup to the eukaryotes, but rather nests within the Metazoa, in a clade containing Schistosoma and Caenorhabditis. Equally curious is the fact that the Trichomonas sequences do not form an outgroup to the Ciliates, Dictyostelium, and the Metazoa, as would be predicted from their status as protist stem taxa, but rather nest within the Dictyostelium (Amoebozoan) + Metazoan subclade. However, this result does not have very strong statistical support, as can be seen from the bootstrap value of 28 (implying that the sister relationship between Trichomonas and Dictyostelium sequences is only supported by a small plurality rather than a majority of trees).

Parsimony-based phylogenies, on the other hand, give incoherent results, such as Dictyostelium nesting within metazoa, falsely suggesting that protostome animals (worms) are more closely related to slime molds than they are to deuterostomes (echinoderms and chordates). The same results were obtained whether one executed a heuristic search or found a global optimum using branch and bound. These results were probably a consequence of the fact that the aligned DNase II sequences are highly divergent due to the ancient branching events separating the lineages in what appears not to be a highly conserved sequence (as an illustration of how extensive sequence divergence in DNase II can be, the gene sequence in Tetrahymena is notably longer than that of its fellow ciliate Paramecium).

Parsimony-based methods applied to such sequences tend to be subject to “long branch attraction” (Felsenstein, 1978), where extensive divergence erases evidence of common ancestry among close relatives and leads with high probability to convergence between distantly related taxa. It has been argued, as seems to be the case in these trees, that likelihood-based methods are less subject to this artifact. Specifically, it is clear that parsimony-based phylogenies are misleading, because the parsimony trees (not shown) place Dictyostelium in a subclade with Caenorhabditis and Schistosoma. It is obviously the case that slime molds are not more closely related to worms than worms are to other metazoans, so no credence can be placed in the phylogenetic positions of DNase II sequences from the parsimony-based reconstruction.

5. Discussion

5.1. DNase II origins

Despite the uncertainties in both eukaryotic phylogeny and in the status of DNase II in a number of key taxa, evaluating the distribution of the gene in Fig. 1A–C allows one to compare competing models for origins, losses, and transfers of DNase II. The black shaded branches represent lineages with confirmed DNase II, the white, confirmed absences. The grey areas or lines in terminal branches represent an uncertain status due to either incomplete data (such as Euglena) or ambiguous matches (Volvox, etc.). The shading on internal branches represents hypothesized points of origin: grey for lower branches due to ambiguity, black for crown internal branches when absences are unequivocally due to secondary loss.

A number of assumptions are made in analyzing the phylogenetic distribution of DNase II. The first is the fact that DNase II is in many ways a unique molecule. Attempts to identify homologous protein families or a possible ancestral molecule based on sequence homology have not been successful. Cymerman et al. (2005) and Schaefer et al. (2007) have proposed a phospholipase origin for DNase II based on secondary structure similarity and some shared motifs (113HTK115 and 295HSK297). However, in BLAST searches or Clustal alignments of DNase II against Phospholipase-D sequences, the alignment scores and e-values do not strongly suggest homology.

In any case, DNase II and phospholipase-D’s are too divergent for construction of phylogenetic trees from aligned sequences. Even if the proposed relationship is correct, it is clear that DNase II diverged extensively from any homologous genes. Furthermore, DNase II is characterized by enough unique, information-rich sequence properties that make multiple convergent origin (homoplasy) of DNase II in different clades highly unlikely. As a result, a single origin for DNase II can be reasonably postulated.

In contrast, it is proposed that DNase II can be readily pseudogenized and lost independently in many lineages. A number of issues suggest that this is a reasonable assumption. It is certainly true that DNase II performs a number of vital functions in the metazoa, including the degradation of DNA from engulfed cells following apoptosis. Organisms with DNase II downregulated or knocked down tend to accumulate extracellular DNA during development (Evans and Aguilera, 2000). However, this is probably not an important function in unicellular or even primitively multicellular (colonial) protists.

As has been demonstrated by Lyon et al. (2000), DNase II is active in the gut of Caenorhabditis, which feeds on bacteria and other microbes. In the nematode gut, DNase II appears to be involved in metabolizing the abundant DNA in the nuclei of the ingested cells in the acidic gut environment, and it undoubtedly plays the same role in many unicellular bacteriotrophs. Phagocytosis, and more specifically bacteriophagy, appears to be quite ancient in the eukaryota (Cavalier-Smitth, 2002). It is ubiquitous among free-living, obligate heterotrophs (including primitive Excavate clades), and is quite widespread among parasitic and some autotrophic forms as well. Indeed, Cavalier-Smith has argued that phagocytosis is what made endosymbiosis and the defining organelles and internal organization of the eukaryotic cell possible.

Having a nuclease that is constitutively active at low pH allowed phagotrophy protists to metabolize nucleic acids within membrane-bound vesicles such as lysosomes. Consequently, one should expect to find DNase II in most protists that feed via phagocytosis. Prior to the origin of DNase II, the DNA of prey bacteria may have simply been excreted as waste, or broken down, perhaps suboptimally, with other nucleases. Because there are a number of protists with phagocytotic abilities that do not have DNase II, it is not necessary to suppose that DNase II necessarily co-originated with phagocytosis. Rather, it is proposed that DNase II arose in a phagocytotic, bacteriophagic protist to facilitate the efficient breakdown of prey DNA under acidic conditions, a useful adaptation that would have been normatively maintained in descendant heterotrophic eukaryotes.

However, the hypothesized presence of DNase II as eukaryotic plesiomorphy (at least in crown taxa) is complicated by a number of factors. The first is that among obligate autotrophs (e.g. many algae, higher plants), there is no further need for DNase II, at least not in connection to phagotrophy. Also, one might expect to observe a loss of function in parasites that obtain their metabolites directly from their hosts, a tendency that is more pronounced in intracellular parasites where other significant losses of metabolic function are known. A good case in point here is Entamoeba. While it is an Amoebozoan allied to Dictyostelium (if one accepts the interpretation of Bapteste et al., 2002 and others, as seen in Fig. 1B) this organism lacks DNase II. The presence of the enzyme in slime molds strongly suggests that its absence in Entamoeba (which, as a parasite, appears to have lost or reduced a number of key metabolic pathways and organelles, including mitochondria) is due to secondary loss. Otherwise, it would be necessary to posit independent origin in slime molds and metazoa, along with the various “lower” taxa. Similarly, DNase II is apparently absent in parasitic Alveolates such as Toxoplasma and Plasmodium, while being well-documented in their free-living ciliate allies such as Tetrahymena and Paramecium.

Consequently, in the absence of any selective pressure to maintain DNase II activity in either obligate autotrophs or in intracellular parasites, it is likely that the gene for DNase II would rapidly pseudogenize due to mutational loss of function. As further mutations accumulate, the pseudogene itself would no longer be recognizable, amounting to loss not only of function but of homologous sequences.

The final process of possible interest in explaining the gene’s distribution is horizontal transfer. Although horizontal transfer of genetic material between distantly related bacteria is quite commonplace, and is bacterial acquisition of eukaryotic genetic material is not uncommon (Jain and Rivera, 1999). It is almost certain that Burkholderia acquired DNase II via transformation from the genome of some metazoan, most likely a soil-dwelling worm (as originally proposed by MacLea et al., 2003). This is strongly suggested by the phylogeny of DNase II (Figs. 3 and 4) and is consistent with what is known of the habits of this bacterium. On the other hand, horizontal gene exchange between eukaryotes is relatively rare, though not undocumented (Bapteste et al., 2005). As a result, horizontal transfer will be considered as a possibility for explaining the distribution of DNase II, but due to its rarity among eukaryotes, ad hoc explanations involving gene transfer will be rejected when other explanations (namely, frequent losses) can be invoked.

First, if one accepts the bikont–unikont dichotomy proposed by Cavalier-Smith and others, then the only plausible explanation for the presence of DNase II in the two lineages is that the gene arose very early in the history of eukaryotes, before the bikont and unikont lineages diverged. Consequently, even the absences in primitive Excavate clades are most likely due to secondary losses. Hence, the most basal branches in Fig. 1A are shaded black to indicate DNase II plesiomorphy in eukaryotes.

The trees in Fig. 1B and C also strongly support early origin, but leave some other possibilities open. The presence of DNase II in Trichomonas strongly supports this claim, as does the likely (though not indisputable) presence in another Excavate, Reclinomonas. DNase II plesiomorphy is particularly likely if one accepts the interpretation of Stiller and Harrell (2005) where Reclinomonas is an ally of the Metamonads (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, even if one accepts the argument (Edgcomb et al., 2001; Simpson et al., 2005) that Reclinomonas is an ally of the Euglenozoa, this still suggests an early origin. Nor can the existence of the gene in Euglena be ruled out at this time, given the strong experimental evidence for DNase II-like activity in this organism (Ikeda and Takata, 2002) and the incomplete status of the genomic data.

Nevertheless, there are a number of anomalies that still need to be accounted for if one posits eukaryotic plesiomorphy of DNase II in accordance with the phylogenies in Fig. 1B and C. The first is that DNase II is absent in Giardia, in contrast to its presence in Trichomonas. While Giardia is a parasite, so is Trichomonas. Both organisms can form lysosome-like organelles with acid phosphatase activity (for instance). Since neither organism is an intracellular parasite and both are capable of phagotrophy, it is necessary to account for why it has been lost in one and present in the other taxon.

Using Fig. 1B and C as model references for eukaryotic evolution, two competing hypotheses will be considered. One possibility, suggested by the presence of DNase II in Trichomonas, is that DNase II arose very early in eukaryotes, and is perhaps a plesiomorphic trait for all protists. If this hypothesis is accepted, then at the minimum one may have to account for loss in the Euglenozoan clade, as well as losses in the red algae, higher plants, and fungi. The alleged absence in the Euglenozoa is difficult to account for since there are taxa such as Euglena itself that are neither parasites nor obligate autotrophs (Euglena feeds through phagotrophy as well as having facultative photosynthetic capabilities).

The interpretation of DNase II being ancestrally present in Metamonads and all “higher” eukaryotes apart from secondary losses is somewhat confounded by the phylogeny of the DNase II sequences themselves. If DNase II is plesiomorphic in the eukaryotes, then the DNase II gene tree should be congruent with the eukaryotic species tree. One should expect that Trichomonas DNase II should be an outgroup to the sequences from the other organisms. In fact, an unrooted tree (Fig. 3) of DNase II sequences shows that the Trichomonas sequences form a subclade with Dictyostelium rather than an outgroup to crown eukaryotes. In this tree, the ciliate taxa form the outgroup, while the Reclinomonas sequence is more closely allied to other crown taxa. This result is not well-supported (i.e. the node uniting Trichomonas with Dictyotelium has a bootstrap value of 0.28), but it nevertheless raises the intriguing possibility that Trichomonas acquired the enzyme through horizontal transfer from some higher eukaryote, an interpretation that would be particularly strengthened if the sequence were indeed confirmed to be absent in other Excavates.

The alternative to early origin in eukaryotes, in other words, is that DNase II antedates the divergence of the Excavate clades from the crown eukaryotic taxa, and that the presence of DNase II in Trichomonas is therefore an anomaly due to lateral transfer, not unlike its occurrence in a single bacterial species. Since the presence of DNase II in Alveolates is indisputable, the trees in Fig. 1A and B both place an origin (at latest) at the node separating the Excavate clades from the crown taxa. That the two trees dispute the affinity of Alveolates and Heterokonts, or place red algae and “Amoebozoa” at different positions of the tree does not affect this interpretation.

In summary, while DNase II plesiomorphy in eukaryotes is very strongly supported by a number of data (likely presence in Reclinomonas, presence in Trichomonas, wide distribution in crown taxa), there remain a number of ambiguities (due to notable absences in stem taxa and the phylogenetic position of the Trichomonad sequence) that make it impossible to exclude alternative explanations such as later origin and horizontal transfer definitely, at least until more sequence data becomes available and the phylogeny of the eukaryotes becomes better resolved.

5.2. Losses of DNase II

Losses among “crown” taxa that need to be accounted for include the apparent absence of DNase II in red algae, higher plants, and fungi. Because the status of the gene in green algae is uncertain (although the data from Volvox suggest presence of homologous sequences), the first two absences could be due to a single loss in the red algae + plant subclade, or at least two independent losses in the red algae and the higher plants, if the homolog is indeed present in green algae such as Volvox. For the internal branches, a black shading indicates likely plesiomorphy (on the grounds of a parsimony argument in which multiple origins and extensive horizontal transfer are unlikely), while grey shading of the internal branches implies ambiguity in the point of origin.

The uncertain status of the gene in green algae may in fact be quite revealing in itself. As unicellular algae probably evolved from heterotrophic protist ancestors, it is quite likely that DNase II and probably other enzymes involved in phagotrophy and digestion in lysosomes would have become pseudogenized. It is possible that the limited (but significant) matches seen in Volvox are remnants of a gene that is already on its evolutionary way out (this is a better argument than it is likely to be there—see comments above), and subsequently masked completely in the higher plants (descendants of green algal lineages) due to a long history of accumulated mutations. It should be noted that the Prasinophycea, which are thought to be the most primitive green algae, are mixotrophic, capable of both photosynthesis and phagotrophy. It is quite likely that DNase II remains present and active in this lineage, and has subsequently been reduced or lost in the “higher” obligate autotrophic green algae. There is an in-progress genome project for Ostreococcus, a representative Prasinophyte, but searches of the available sequence have failed to produce significant matches for DNase II homologs (likely due to extensive missing sequence data).

The same may be true in Diatoms, which are autotrophic Heterokonts. The partial matches of Phaeodactylum sequences against the slime mold query may also be indicative of the pattern proposed for the comparatively weak and incomplete matches with green algae: again indicative of a DNase II gene in the process of being lost.

To test these hypotheses as they relate to plants and algae, it would be of interest to look at whether a similar pattern of partial loss in unicellular algae versus complete loss in plants can be seen in other enzymes associated with phagocytosis and lysosomal digestion. It would also be of great value to look at a wider range of green and red algal genomes once they become available to determine whether DNase II “relics” appear in more complete or incomplete form among them. The same would be of interest in brown algae (Heterokonts) and their allies, as an independent study in the loss of phagotrophic function in autotrophic eukaryotes with cell walls.

The other notable absences that are almost certainly due to secondary loss are in fungi and in a number of parasitic taxa. The absence in all fungi assayed may seem curious at first, given that fungi are heterotrophs and the majority are free-living. Furthermore, fungi are close allies of the metazoa and (if one accepts the results of Bapteste et al., 2002) of Amoebozoans such as Dictyostelium, both of which definitely possess DNase II. The most likely explanation then is due to the fact that fungi, like plants, have cell walls (chitin rather than cellulose) and are therefore incapable of phagotrophic feeding (e.g. Barr, 1992). Instead, fungi are saprophytes that secrete their enzymes externally and absorb the products of external digestion through their cell walls. Consequently, one should expect to find a loss of enzymes such as DNase II that are associated with phagotrophy and lysosomal digestion.

The absence of DNase II in Apicomplexan parasites (such as Toxoplasma and Plasmodium) is almost certainly a secondary loss also, since their free-living ciliate allies such as Paramecium and Tetrahymena both have the enzyme. Similarly, if one accepts the phylogenies in Fig. 1A and B which place Entamoeba in a monophyletic group allied to Dictyostelium (rather than as a basal ally of the Metamonads, as in Fig. 1C), then its lack of the gene is due to secondary loss as well. Entamoeba is known for its lack of a number of key metabolic pathways and cell structures (including mitochondria), which are widely accepted to be a consequence of secondary loss. The same is likely true of DNase II.

6. Concluding remarks

In spite of some remaining ambiguities, this study has addressed a number of questions about DNase II’s evolutionary history. Contrary to prior studies (e.g. MacLea et al., 2003), which considered DNase II to be a gene of higher metazoans with anomalous presence in some unicellular organisms, the gene is now confirmed to have a fairly broad phylogenetic distribution. It arose at the very latest prior to the phylogenetic branch that lead to the Alveolate taxa, thereby being plesiomorphic in crown eukaryotes.

However, it is far more likely that DNase II is even more ancient than that if one accepts the evidence for its presence in Reclinomonas at face value and discounts the possibility of horizontal transfer of the gene to Trichomonas. The main evidence for latter origin and lateral transfer comes from the phylogenetic position of Trichomonas sequence, which is weakly supported to begin with, and by the uncertain status of the gene in a number of Excavate taxa.

Under the more plausible explanation, DNase II co-evolved with the early eukaryotic cell itself, as a critical enzyme facilitating the plesiomorphic eukaryotic cell function of phagotrophy. Its rather spotty distribution is then almost certainly due to loss of phagocytotic function in parasites, autotrophs, and saprophytic fungi. As additional sequence data from free-living stem taxa becomes more widely available, alternative explanations to early origin can probably be definitively refuted.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kimmen Sjolander (University of California, Berkeley) for early discussions and input on the phylogeny of DNase II and its paralogs. The senior author wishes to express his gratitude to the following individuals for comments on such varied topics related to the cell biology, genetics and evolution of various eukaryote clades: Brian Leander, John Stiller, David Patterson, Tor Erik Rusten, Joanne Ellzey, Stephen Dellaporta, Ana Signorovitch, Bernard Degnan, and William Loomis. This work was partially supported by MBRS-SCORE (S06 GM8012-36) subproject grant to R.J.A. and an institutional NIH RCMI Grant 2G12RR08124.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Alignments between query sequences and their matches with sequences from various organisms can be found together with figure legends and annotations. Where relevant, the HSK motif of the catalytic site is highlighted by arrows. Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.11.033.

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bapteste E, Brinkmann H, Lee JA, et al. The analysis of 100 genes supports the grouping of three highly divergent amoebae: Dictyostelium, Entamoeba, and Mastigamoeba. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2002;99:1414–1419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032662799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bapteste E, Susko E, Leigh J, et al. Do orthologous gene phylogenies really support tree thinking? BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2005;5:33–43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr DJS. Evolution and kingdoms of organisms from the standpoint of a mycologist. Mycologia. 1992;84:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smitth T. The phagotrophic origin of eukaryotes and phylogenetic classification of Protozoa. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2002;52:254–297. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-2-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EEY. Phylogeny and metasystematics of phagotrophic heterokonts. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2006;62:388–420. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordonnier C, Bernardi G. A comparative study of acid deoxyribonucleases extracted from different tissues and species. Canadian Journal of Biochemistry. 1968;46:989–995. doi: 10.1139/o68-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cymerman IA, Meiss G, Bujnicki JM. DNase II is a member of the phospholipase D superfamily. Bioinformatics. 2005;1:3959–3962. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgcomb VP, Roger AJ, Simpson AGB, et al. Evolutionary relationships among “Jakobid” flagellates, as indicated by alpha- and beta-tubulin phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2001;18:514–522. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CJ, Aguilera RJ. DNase II: genes, enzymes, and function. Gene. 2000;322:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Cases in which parsimony or compatibility methods will be positively misleading. Systematic Zoology. 1978;27:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Inferring Phylogenies. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Howell DP, Krieser RJ, Eastman A, Barry MA. Deoxyribonuclease II is a lysosomal barrier to transfection. Molecular Therapy. 2003;8:957–963. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda S, Takata N. Deoxyribonuclease-II purified from Euglena gracilis SM-ZK, a chloroplast-lacking mutant: comparison with porcine spleen deoxyribonuclease-II. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B. 2002;131:519–525. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(02)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R, Rivera MC, Lake JA. Horizontal gene transfer among genomes: the complexity hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1999;96:3801–3806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawane K, Fukuyama H, Kondoh G, et al. Requirement of DNase II for definitive erythropoiesis in the mouse fetal liver. Science. 2001;292:1546–1549. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5521.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawane K, Ohtani M, Miwa K, et al. Chronic polyarthritis caused by mammalian DNA that escapes from degradation in macrophages. Nature. 2006;443:998–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature05245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieser RJ, Eastman A. Deoxyribonuclease-II: structure and location of murine genes, and comparison with Caenorhabditis and human homologs. Gene. 2000;252:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieser RJ, MacLea KS, Longnecker DS, et al. Deoxyribonuclease II alpha is required during the phagocytic phase of apoptosis and its loss causes perinatal lethality. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2002;9:956–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. DFF, a heterodimeric protein that functions downstream of Caspase-3 to trigger DNA fragmentation during apoptosis. Cell. 1997;89:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon CJ, Evans CJ, Bill BR, Otsuka AJ, Aguilera RJ. The C elegans apoptotic nuclease Nuc-1 is related in sequence and activity to mammalian DNase II. Gene. 2000;252:146–154. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLea KS, Krieser RJ, Eastman A. A family history of deoxyribonuclease II: surprises from Trichinella spiralis and Burkholderia pseudomallei. Gene. 2003;305:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramoto Y, Watanabe A, Nakamura T, Takabe T. Enhanced expression of nuclease genes in leaves of barley plants under salt stress. Gene. 1999;234:315–321. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RDM. TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Computer Applications in the Biosciences. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DJ. The diversity of eukaryotes. American Naturalist. 1999;154:S96–S124. doi: 10.1086/303287. Supplement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seong CS, Varela-Ramirez A, Aguilera RJ. DNase II deficiency impairs innate immune function in Drosophila. Cellular Immunology. 2006;240:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer P, Cymerman IA, Bujnicki JM, Meiss G. Human lysosomal DNase II-alpha contains two requisite PLD-signature motifs: evidence for a pseudoimeric structure of the active enzyme species. Protein Science. 2007;16:82–91. doi: 10.1110/ps.062535307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin HD, Park BL, Cheong HS, Lee HS, Jun JB, Bae SC. DNase II polymorphisms associated with risk of renal disorder among systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;50:107–111. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson AGB, Inagaki Y, Roger AJ. Comprehensive multigene phylogenies of excavate protists reveal the evolutionary positions of primitive eukaryotes. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2005;23:615–625. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogin ML. Early evolution and the origin of eukaryotes. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 1991;1:457–463. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogin ML. History assignment: when was the mitochondrion founded. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 1997;7:792–799. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogin ML, Silberman JD. Evolution of the protists and protistan parasites from the perspective of molecular systematics. International Journal of Parasitology. 1998;28:11–20. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiller JW, Hall BD. Long branch attraction and the rDNA model of early eukaryote evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1999;16:1270–1279. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiller JW, Riley J, Hall BD. Are red algae plants? A critical evaluation of three key molecular data sets. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2004;52:527–539. doi: 10.1007/s002390010183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiller JW, Harrell L. The largest subunit of RNA polymerase II from the Glaucocystophyta: functional constraint and short-branch exclusion in deep eukaryotic phylogeny. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2005;5:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties, and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JW. The Origin of Phyla. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Woese C. The universal ancestor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1998;95:6854–6859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YC, Stanfield GM, Horvitz HR. Nuc1, a C. elegans DNase-II homolog, functions in intermediate step of DNA degradation during apoptosis. Genes and Development. 2000;14:536–548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye M, Zheng H, Ying F, et al. Purification and characterization of acid deoxyribonuclease from the cultured mushroom Cordyceps sinensis. Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2003;37:466–473. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2004.37.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccon A, Zuccon D. MrEnt v1.2, distributed by the authors. Department of Vertebrate Zoology and Molecular Systematics Laboratory; Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm: 2006. [Google Scholar]