Abstract

Purpose

To fully understand the effects of an image processing methodology on the comparisons of regional patterns of brain perfusion over time and between subject groups.

Materials and Methods

Two brain normalization methods were compared using images of elderly controls and subjects with MCI and AD: the normalization package of statistical parametric mapping (SPM2) and a fully deformable model (FDM). The performance of these two normalization methods was quantitatively evaluated based on two criteria: (1) the alignment accuracy of five brain structures to the colin27 reference volume; and (2) impact of spatial normalization methods on the sensitivity of perfusion magnetic resonance imaging (pMRI).

Results

The delineations of all five brain structures had significantly higher overlap with expert manual tracings using FDM compared to SPM (two-tailed, p < 0.025). When applied to the biostatistical analysis of CBF maps, a larger number of statistically significant voxels was identified from FDM compared with SPM2 regardless of the effects of the threshold and smoothing kernel.

Conclusion

The greater degree of deformation freedom associated with FDM may yield more accurate region matching and higher statistical sensitivity in identifying regions of CBF differences between elderly groups with prevalent late-life neurodegenerative conditions.

Keywords: spatial normalization, perfusion, deformable model, MRI, image registration

Introduction

Perfusion magnetic resonance imaging (pMRI) directly measures the rate at which blood is delivered to the tissue, and therefore it is an important hemodynamic parameter. pMRI was applied to study pathophysiology of the central nervous system (CNS) diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, ischemia, epilepsy (1–4). Perfusion changes were demonstrated to be an important biomarker in the CNS diseases. Therefore, pMRI is a very useful technique for identifying the high-risk candidates for disease and permitting early detection and therapeutic prevention (5,6).

To detect the voxelwise change of brain perfusion in the different stages of CNS diseases, the brain perfusion volumes from different subjects need to be transformed to the same stereotactic volume (referred herein as the reference volume) to account for anatomical variability. The transformation process is widely referred as spatial normalization. Spatial normalization of elderly brains is a challenging issue. Brain regions vary broadly between individuals due to heterogeneous patterns of age-related and pathology-related atrophy. Deformation variability across brain structures requires an accurate normalization method to match the brain structures between individual brains and the reference volume. Therefore, the performance of spatial normalization on elderly brains may have an important effect on group comparisons when applied to functional imaging. We seek to determine which spatial normalization technique we should adopt for pMRI among the available normalization techniques, and how different normalization techniques impact the pMRI results.

A variety of spatial transformation models were proposed for brain spatial normalization. Early models were linear or piecewise linear (7–9), thus correcting for location, orientation and overall size. Nonlinear transformations enable a more detailed matching of brain structures through higher-order mathematical models such as discrete cosine transformation (DCT) basis functions (10) or polynomial basis functions (11). The number of degrees of freedom in these models may be adjusted by adding more basis functions, and therefore higher degrees of spatial deformation. Typically, tens to hundreds of degrees of freedom are used. Fully-deformable alignment methods generate a dense mathematical description of the motion of each image voxel, allow a high degree of deformation, and have a large number of degrees of freedom (12–16). Fully-deformable algorithms provide high precision matching of fine brain structures between individual brain and the reference volume. However, some transformation models include numerical parameters whose values need to be specified by the users, and the accuracy of image alignment may depend critically on the settings of those parameters (17).

This paper compares the performance of two broadly-disseminated nonlinear alignment methods - a DCT-based method and a fully-deformable one - for applications in perfusion MR imaging. Previous findings by Carmichael, et al and Wu, et al (18,19) showed that the fully-deformable method provides higher anatomical precision than competing nonlinear and linear methods for hippocampus segmentation in structural MRI of elderly patients and for quantifying BOLD fMRI activation in young subjects’ right hippocampus and anterior cingulate gyrus. In these studies, the normalization methods were used to register the reference volume to the subject volume to carry anatomical labels to the individual. We register from the subject to the reference space in order to compare the voxel-level perfusion difference, which is complementary to the previous methods. Moreover, the normalization accuracy is evaluated for more brain structures across all subjects in a single, unified measure. While many papers compared linear and nonlinear spatial normalization algorithms in terms of precision of anatomical correspondence when presenting new normalization algorithms (11,20–24), few other studies compared the accuracy of multiple nonlinear methods (16,17,25). Furthermore, the spatial normalization has an important impact on statistical sensitivity of functional images. While the impact of spatial normalization on PET (25–27) and BOLD fMRI functional images has been addressed (28,29), the effects of normalization methods on the sensitivity of pMRI analyses are unclear.

We evaluated nonlinear normalization methods from two widely available automated software packages. Statistical parametric mapping (SPM, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) is a popular software package for brain image analysis with a DCT-based normalization routine. A fully deformable model (FDM), combining piecewise linear alignment with the nonlinear Demons algorithm, is freely available in the ITK software package (15) and is highly similar to Chen’s method (14), although we used the original implementation of Chen’s method. We conducted quantitative comparisons to: 1) investigate the accuracy of the spatial normalization algorithms for establishing correspondence of brain anatomical regions between individual brains and a reference volume; and 2) globally assess the effects of the normalization methods on the sensitivity of biostatistical analysis of continuous arterial spin labeled (CASL) pMRI in elderly brains.

Methods

Subjects

The Pittsburgh Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Cognition Study was a population-based study conducted in 2002/03 to determine the incidence of dementia and MCI. Participants were diagnosed as probable Alzheimer’s disease (AD) according to the criteria of McKhann, et al. (30), probable mild cognitive impairment (MCI) according to the criteria of Lopez, et al. (31), or cognitively normal. One hundred eighty eight participants (referred herein as the subject database) had an MRI of the brain 2002–03. Two study groups were selected from the subject database. One study group with 10 subjects was randomly selected to assess the accuracy of normalization methods. The other study group with 45 subjects was selected to evaluate the effects of normalization methods on biostatistical analysis of pMRI.

MR imaging

All data were acquired using a 1.5T GE Signa system (Milwaukee, WI, LX) after each subject provided informed consent either directly, or by their caregiver, and passed standardized MRI screening. A coronal T1-weighted spoiled gradient-recalled echo (SPGR) volume covering the whole brain was acquired for each subject (3D acquisition with 124 slices; Flip Angle: 30°; Matrix: 256 × 192; Slice Thickness: 1.5 mm and zero spacing; TE: minimum Full; TR: 25 ms, FOV: 24 x 18 cm, rBW: 16 kHz). For the quantitative perfusion maps, blood flow velocities, perfusion rates and T1 relaxation times were measured in each subject using phase contrast (PC) Cine, multi-slice CASL, and saturation recovery MRI, respectively. Multi-slice CASL used Alternating Single and Double (ASD) adiabatic inversions (32) (3.7 s pulse train at 92% duty cycle) and ramp-sampled echo-planar imaging (EPI) to acquire 19 contiguous axial slices (Matrix: 64 × 64; Slice Thickness: 5 mm with 0 spacing; TE: 21 ms; FOV: 20 cm; rBW: 76 kHz; Acquisition Time: 1 s/volume; Transit Delay: 700 ms; Flip Angle: 90°; 50 signal averages). Images were acquired sequentially in superior to inferior order to avoid RF perturbation of the endogenous tracer as it moved superiorly into the brain and to minimize intensity discontinuities associated with interleaved acquisitions. The inversion efficiencies in the internal carotid arteries were calculated for each subject based on B1 maps and phase contrast (PC) cine velocimetry at the label plane (33).

Normalization Methods

Description of normalization methods

SPM

The first stage of SPM (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) estimates a 12-parameter affine geometric transformation and a single intensity scaling parameter. In the second stage, a nonlinear deformation is estimated in the form of a linear combination of the 3D DCT basis functions. Parameter estimation in both stages is based on iterative Gaussian-Newton minimization of a cost function that measures the sum of squared differences (SSD) in image intensities between the warped subject volume and the reference volume at sampled points in the reference space. The sampled points are every K-by-K-by-Kth voxel in the reference volume to reduce the computational cost of evaluating the cost function. The spatial normalization method of SPM is intentionally designed to generate spatially smooth deformations, and therefore does not attempt to precisely match every brain feature (23). The SPM normalization algorithm used in the paper is from the SPM2 version of the software package and will henceforth be referred as SPM2.

FDM

The first stage of FDM (14) estimates the parameters of an affine transformation as in SPM2. The second stage is a piecewise-linear model, which takes the estimated parameters from the first stage as a starting point. In the piecewise-linear transformation, a set of control points is chosen and displacements of the control point are estimated. The control points are located on a 3D rectangular grid that covers the reference volume. The method first estimates displacements for a 2×2×2 grid of control points, and uses these displacements as the starting point to estimate displacements of a 3×3×3 grid of control points, and so on. The displacement of each voxel point in the reference volume is calculated by a trilinear interpolation of the displacements of the eight control points that surround it. Levenburg-Marquardt iterative minimization is used to estimate the displacements of the control points to minimize an SSD cost function at sample points as in SPM. The sample points are chosen as a random selection of K voxels. The third stage is a dense voxel-by-voxel transformation, which takes the estimated parameters from the second stage as a starting point. For the third stage, the displacements [Δx, Δy, Δz] of each voxel [x, y, z] are estimated based on a first-order Taylor expansion of the following equation:

| [1] |

where f(x, y, z) and g(x, y, z) represent the image intensity of the subject volume and the reference volume at the voxel location [x, y, z], respectively. The displacements only depend on the volume g, parameters a and b, and the gradients of subject volume f, and therefore can be computed iteratively at each voxel until the algorithm converges. The parameters a and b of the linear function a · g(x, y,z) + b are multiplicative and additve factors, respectively, that match the overall intensity ranges of the subject and reference volumes. These parameters are estimated from the simple heuristic that the mean and variance of the intensity distributions of the reference and subject volumes should match. The dense voxel-by-voxel phase gives rise to the term “fully-deformable” due to its fully unconstrained geometric transformation. Thus, FDM has the potential precision to match brain features with substantial fine-scale deformation. Because competing normalization methods are more anatomically-constrained than FDM, we chose to investigate FDM to see if the more precise structural matching in FDM can provide added sensitivity to pMRI analysis.

Assessment of accuracy of normalization methods

Ten subjects (mean age 82 ± 3.4 years: 4 normal controls, 3 MCI subjects, 3 AD subjects) were randomly selected from the subject database. The 10 SPGR volumes were cropped to remove extracranial regions using the Brain Extraction Tool (BET) of the FSL software package (Oxford Center for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Oxford University, UK, http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/). We chose the standard Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI, http://imaging.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/imaging/MniTalairach) in colin27 (with voxel size 1 × 1 × 1 mm3) (34) as the reference volume because high-resolution tracings of anatomical brain structures are available and it is a commonly used reference. Five regions (left posterior cingulate gyrus, left cuneus and calcarine, left hippocampus, right thalamus and right putamen) were analyzed because they are suspected regions of atrophy and cerebrovascular change in healthy aging and AD (35-38), and their borders are easy to delineate for the brain.

The right thalamus and right putamen were traced in axial views, and the left posterior cingulate gyrus, left cuneus and calcarine and left hippocampus were traced in sagittal views, on the subject and reference volumes. Tracings were performed under the supervision of a neurologist. The manually-traced regions served as ground-truth region masks (each region mask is a binary 3D volume in which voxels labeled as the region had a value of 1). The region tracing program was in-house software written in MATLAB.

The intra-rater reliability for the manual tracing of each region was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). For each ROI, five randomly-selected subjects were retraced by the same rater after 2.5 months. The ICCs of the regional volumes were 0.9757 (right thalamus), 0.9793 (right putamen), 0.9864 (left posterior cingulate gyrus), 0.9930 (left cuneus & calcarine) and 0.9872 (left hippocampus).

All 10 cropped brain SPGR volumes were normalized to the reference volume using SPM2 and FDM. The warping parameters of each subject from the normalization were used to warp the five region masks of the subject to the reference space for SPM2 and FDM, respectively. Normalized region masks were obtained using SPM2 and FDM for each region mask of each subject (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Graphical illustration of normalization methods in obtaining normalized region mask and normalized CBF maps. For each subject i, The SPGR (spoiled gradient-recalled echo) volume was cropped to remove extracranial regions using the Brain Extraction Tool (BET) of the FSL software package http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/), the cropped brain SPGR volumes were normalized to the reference volume using method k (1: SPM2; 2: FDM). The warping parameters from the method k were used to warp the region mask j (j=1, …, 5) of the subject i to the reference space to obtain normalized region masks Nkij (normalized region mask from the subject i in region j by method k). The warping parameters from the method k for subject i were also used to warp the CBF map of subject i in the cropped SPGR space to the reference space to obtain normalized CBF map of subject i from method k.

We used the overlap ratio to evaluate the agreement between normalized region masks from each method and the ground-truth region masks of the reference volume. Let the normalized region mask be the set of voxels labeled as the brain structure j (j = 1, …, 5) on the ith (i = 1,…, 10) subject using normalization method k (k=1, 2, i.e. 1 = SPM, 2 = FDM). Let the ground-truth region mask Gj be the voxels labeled as brain structure j on the reference volume. The overlap ratio of brain structure j on subject i based on method k was:

| [2] |

That is, the overlap ratio is the ratio of the number of voxels shared between and Gj, and the total number of voxels in both masks. It gives a measure of the percentage of voxels from the pair of masks that are in common between them. The range of the overlap ratio is 0 to 1; the higher the ratio, the better and Gj overlap.

We also calculated the overall overlap ratio from the 10 subjects for each brain structure j to assess the ability of the methods in removing the anatomical variability. The overall overlap ratio was defined as the percentage of voxels that are shared between all subjects and reference volume for each brain structure and normalization method:

| [3] |

The overall overlap ratio of each brain structure gives a measure how well the normalized region masks from all subjects overlap with the ground-truth region mask from the reference subject. The ratio provides the overlap degree of spatial location of all subjects after normalization. The overlap ratio only reflects the degree of the spatial correspondence between two masks for each subject, but not the simultaneous overlap between all subjects, as the overall overlap ratio does.

Effects of normalization methods on biostatistical analysis of pMRI

Forty-five CHS-CS subjects had optimal CASL MRI scans (Table 1). Scans were excluded from the sample based on the following criteria: radiological evidence of structural or vascular central nervous system (CNS) lesions, history of strokes, or head trauma encephalopathy; evidence of large disparity in blood flow between hemispheres; poor arterial labeling efficiency or execution (less than 60%), excessive patient motion as evidenced in the structural images; excessive image artifacts; and consumption of caffeine within 8 hours of the scan. The 45 corresponding SPGR volumes were also cropped using BET to remove the extracranial regions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Groups

| Characteristic | Controls | MCIs | ADs |

|---|---|---|---|

| # of Cases | 16 | 14 | 15 |

| Age | 82.4 ± 3.8 | 83.5 ± 3.4 | 83.0 ± 3.1 |

| Female/Male | 5/11 | 4/10 | 6/9 |

| 3MSE | 95.1 ± 4.7 | 89.1 ± 10.9 | 87.4 ± 9.5 |

3MSE: Modified Mini-Mental State Examination.

The 45 absolute perfusion (i.e. cerebral blood flow, CBF) maps of gray matter were calculated using the tracer kinetic convolution model of CASL (39). Labeling efficiency was measured and calculated for each subject (33). The gray matter CBF map of each subject was transformed to the cropped SPGR image of the subject by the coregistration algorithm of SPM2.

The 45 cropped SPGR volumes were normalized to the reference volume colin27 using SPM2 and FDM. Transformation parameters for each subject were used to warp the corresponding brain gray matter perfusion map to the reference space. Therefore, two normalized gray matter perfusion volumes were obtained for each subject, using SPM2 and FDM, respectively (Fig. 1). Both SPM2 and FDM used the same interpolation method so that these two methods contain the same partial volume effects.

We smoothed the two normalized gray matter CBF maps (from SPM and FDM) for each subject using the same 6 mm Gaussian kernel. We investigated the effects of spatial smoothing of the pMRI maps on the biostatistical analyses. Specifically, the pMRI maps were smoothed with a 10 mm kernel to compare results with those obtained with a 6 mm Gaussian kernel.

Statistical analysis

Smoothed CBF maps were compared on a voxel-by-voxel basis between the following pairs of groups: a) normal controls and early AD subjects, b) MCI and early AD subjects, and c) normal controls and MCI subjects. At each voxel, a customized one-way ANOVA model was estimated using software written in MATLAB (MathWorks Inc.). The customized algorithm allowed an ANOVA of only those voxels that had defined perfusion values for a majority of subjects in each group; this allowed the statistical analysis to cover a broader brain area than restricting the ANOVAs to voxels in which perfusion was defined for all subjects. Due to variability in scan slice coverage, the algorithm allowed analysis of most cortical voxels. The voxel-level threshold was chosen to identify statistically significant differences between groups (referred as the difference maps). Eta squared (η2) was calculated to measure the effect size map in ANOVA (40). Several voxel-level thresholds (two-tailed p-values of 0.02, 0.01, 0.005, and 0.001) were studied to avoid the biased comparison of a single threshold. The difference maps were further masked using the brain volume mask (i.e. all of the gray matter voxels that have defined perfusion data in a majority of subjects of each group) to avoid smoothing artifacts. SPM2 subroutines were modified to overlay the masked difference maps onto the colin27 brain.

Clusters displayed on the colin27 brain were thresholded at a corrected cluster level of P < 0.05. The cluster-level correction was performed to guard against false positives from multiple comparisons. The correction took into account the voxel-level threshold and the spatial extent of cluster. The corrected P-value was calculated according to the Gaussian random field theory (41). The clusters with a cluster-level P value less than 0.02 were considered as the significant clusters.

Results

Assessment of accuracy of normalization methods

An example of regional alignment of normalized regional mask with ground-truth mask from the two procedures is illustrated in Fig 2. The comparisons of the five overlap ratios measured for SPM2 and FDM are shown in Fig. 3A. For all regions, FDM gives a higher mean overlap ratio than SPM2. Paired two-tailed t-tests were applied for the overlap ratios obtained from SPM vs FDM. The results of the paired t-tests of five overlap ratios are shown in Table 2. The differences in overlap ratios of all five regions were statistically significant (with two-tailed p < 0.025), showing FDM more accurately aligned brain structures from the subject space to the reference space. The low overlap ratio in the posterior cingulate gyrus is due to its small volume in the brain. It appears that certain regions are more affected than others by the normalization process. As shown as p values between SPM and FDM normalization in Table 2, FDM has less improvement on the regional correspondence of cuneus compared with SPM. These differences from the regions reflect the difference between two normalization mechanisms. Because FDM has the ability to produce spatially-complex transformations, it will have the greatest impact over SPM in aligning structures whose shape is complex or whose spatial variability across subjects is large. In elderly subjects, several of the structures evaluated here have complex shape due to cortical folding, including posterior cingulate and cuneus. These structures along with the hippocampus have high inter-subject variability due to age-associated atrophy effects. Additionally, the positions of the thalamus and putamen can vary dramatically between subjects as well, due to high inter-subject variability in ventricular dilation. Therefore, in elderly subjects, we expect FDM to have a significant impact on other brain regions known to have high inter-subject variability due to the aging process, including the prefrontal and entorhinal cortices. However, we stress that the effects of FDM on normalization of these additional regions will need to be measured experimentally. The overall overlap ratios from all 10 subjects are shown in Fig. 3B. For all five brain structures, FDM gives a higher overall overlap ratio than SPM2: 12% higher for the left cuneus and at least 97% higher for the other four brain structures. Therefore, FDM provided more precision than SPM2 to overlay the fine brain structures between different subjects.

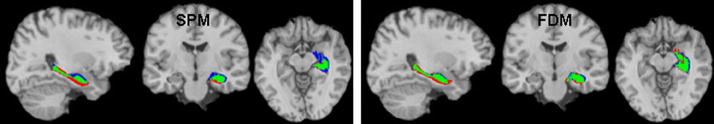

Figure 2.

Illustration of regional alignment (of left hippocampus) with ground-truth mask (in the colin27 reference volume) obtained using SPM2 (left) and FDM (right) for a normal control subject. Green: the intersection of the region and ground-truth masks; Blue: regions in the ground-truth mask not in the region mask; Red: regions in region mask not in the ground-truth mask.

Figure 3.

A) Mean overlap ratios and standard deviations (error bars) and B) Overall overlap ratios of five brain regions: left hippocampus (L Hippo), right putamen (R Putam), right thalamus (R Thala), left cuneus (L cuneu) and left posterior cingulated gyrus (L cingp) over 10 subjects by SPM and FDM. The differences in overlap ratios of all five regions were statistically significant (with two-tailed p < 0.025). No error bars are associated with overall overlap ratios since the overall overlap ratio is a measure which reflects the spatial overlap from all subjects. The low overlap ratio in the posterior cingulate gyrus for the image normalization maybe explained by it small volume in the brain.

Table 2.

Statistical comparison of overlap ratios of five selected regions (n = 10 subjects).

| Regions | Mean overlap of SPM | Mean overlap of FDM | t-values | two-tailed p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Hippocampus | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | −4.72 | 0.0011 |

| Right Putamen | 0.58 ± 0.11 | 0.72 ± 0.03 | −3.75 | 0.0046 |

| Right Thalamus | 0.57 ± 0.09 | 0.70 ± 0.03 | −4.60 | 0.0013 |

| Left Cuneus | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.64 ± 0.03 | −2.77 | 0.0219 |

| Left Posterior Cingulate | 0.23 ± 0.10 | 0.48 ± 0.07 | −7.22 | 0.00005 |

Effects of normalization methods on biostatistical analysis of pMRI

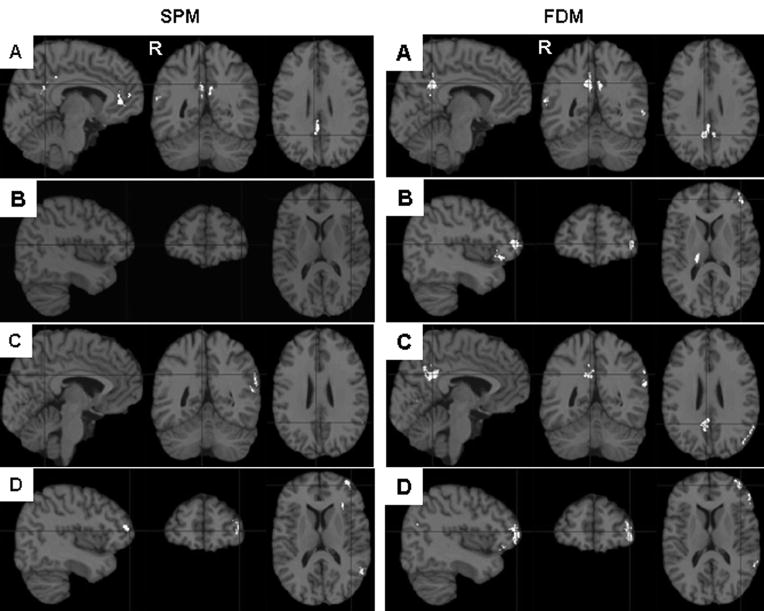

With the 6 mm Gaussian smoothing kernel, FDM consistently shows a much larger region size for each significant region in group comparisons compared to SPM2 for all voxel-level thresholds, although FDM shows only slightly bigger region sizes than SPM2 for the CBFControl > CBFMCI case (Fig. 4). Different voxel-level thresholds resulted in similar comparison of region sizes between SPM2 and FDM. We illustrate the performance difference between SPM2 and FDM in a voxel-level threshold of 0.02 (Fig. 5) for better visibility. The clusters with cluster-level P value less than 0.02 from Fig. 5 are shown in Table 3. With FDM, the total number of voxels with statistical significance was 5854, which was 2.21 times greater than SPM2. FDM identified 2.5 times more clusters of statistical significance than SPM2 (FDM: 10 clusters vs. SPM2: 4 clusters). We also observed markedly larger sizes (40% or more) for most of the statistically significant FDM clusters, with the exception of similar sizes of clusters computed from the comparison between normal controls and MCI subjects.

Figure 4.

Comparison of voxel number for SPM2 vs. FDM for the cluster regions which are statistically significant (shown in Table 3) with different voxel-level threshold: (A) p = 0.02; (B) p = 0.01; (C) p = 0.005; (D) p = 0.001. The seven regions in horizontal axis are as: 1(posterior cingulate region, which combines left and right side, in Control > MCI), 2(Right inferior parietal, in Control > MCI), 3(left orbital frontal, which combines two clusters, in MCI > AD), 4(left inferior parietal, in MCI > AD), 5(right posterior cingulate region, in Control > AD), 6 (Left orbital frontal, which combines two clusters, in Control > AD), 7(left inferior parietal, in Control >AD). FDM consistently shows large region sizes in group comparison compared to SPM2 for all voxel-level thresholds, although FDM shows only slightly bigger region sizes than SPM2 for Control > MCI case.

Figure 5.

Comparison of statistically significant regions (white) between groups (normal controls, MCIs and ADs) from SPM2 and FDM. A) CBFcontrol > CBFMCI at left and right posterior cingulate gyrus, the total size of the cluster is smaller from SPM2 normalization than from FDM normalization; B) CBFMCI > CBFAD at left orbital frontal cortex, the cluster is missing from SPM normalization; C) CBFcontrol > CBFAD at right posterior cingulate gyrus, the cluster is missing from SPM2 normalization; D) CBFcontrol > CBFAD at left orbital frontal cortex, the cluster is much smaller from SPM2 normalization than from FDM normalization. Clusters displayed on the colin27 brain were thresholded at a corrected cluster level of P < 0.05 by using a voxel-level threshold p < 0.02 (only clusters with P-value less than 0.02 were considered as statistically significant and listed in Table 3). The clusters with a corrected cluster level of P > 0.05 were removed from the display. The right side of the brain is labeled as R.

Table 3.

Comparison of Cluster-level statistics between groups from FDM and SPM (n = 45 subjects).

| Cluster Location | Cluster size & corrected P-value from SPM | Cluster size & corrected P-value from FDM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBFcontrol > CBFMCI | R posterior cingulate ext inf parietal | 1383* | 0.0001 | 1024 | 0.0003 |

| L posterior cingulate ext inf parietal | 431 | 0.0060 | |||

| R inferior parietal | 233 | 0.0179 | 236 | 0.0180 | |

| CBFMCI > CBFAD | L orbital | 0

0 |

N/A

N/A |

340

249 |

0.0096

0.0170 |

| L inferior parietal | 0 | N/A | 254 | 0.0164 | |

| CBFcontrol > CBFAD | R posterior cingulate ext inf parietal | 81 | N.S.⊥ | 1155 | 0.0002 |

| L orbital | 551

0 |

0.0042

N/A |

793

669 |

0.0011

0.0028 |

|

| L inferior parietal | 395 | 0.0116 | 703 | 0.0019 | |

L posterior cingulate and R posterior cingulate became one cluster.

Not significant for corrected P-value 0.02.

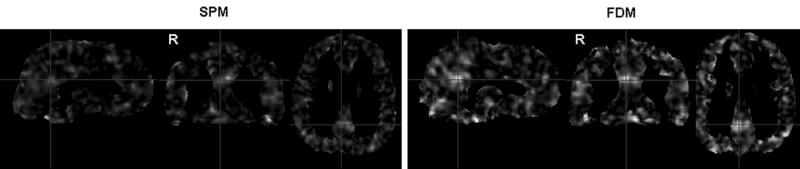

For normal controls vs. MCIs, the left and right posterior cingulate area yielded one cluster in SPM2. The total size of the two separate clusters in that area from FDM was larger than the one cluster from SPM2, while the sizes of the right superior parietal lobe clusters measured from FDM and SPM2 were almost equal. Not only were small clusters of statistical significance from FDM normalization not observed in SPM2, but a large cluster (right posterior cingulate gyrus from normal controls vs. AD, 1155 mm3) was not detected as a significant cluster in SPM2. The comparison of the effect size maps between SPM2 and FDM (Fig. 6) also reveals the better sensitivity of FDM normalization in group comparison than SPM2.

Figure 6.

Effect size maps calculated as Eta-squared (η2) in one-way ANOVA (for testing the CBF difference among normal controls, MCI and AD subjects) from SPM2 (left) and FDM (right) normalization.

Using the 10 mm Gaussian smoothing kernel, we still observed significantly larger sizes for the FDM clusters compared with SPM2 clusters except in the comparison of normal controls and MCIs. However, both SPM2 and FDM lose the sensitivity with the larger smoothing kernel. For the 10 mm Gaussian kernel, SPM2 only identified statistical significance in the posterior cingulate region in the comparison of normal controls and MCIs, and FDM kept all the regions except the two regions for MCIs vs. ADs compared with the 6 mm kernel. The nonsignificant cluster (right posterior cingulate gyrus in the comparison of normal controls and ADs in Table 3) from SPM2 increased in size with the 10 mm kernel, but its corrected cluster-level P-value is 0.14 (still not significant). Generally, FDM identified more clusters and larger cluster sizes than SPM2, independent of the smoothing kernel size.

The increased precision of FDM came at the cost of longer computation time. We ran the two normalization algorithms on the same 5 brains on the same computer (2.8 GHz Pentium III Dell dimension 2800, Fedora Core 2 Linux OS). It took 10 minutes for SPM2, and 32 minutes for FDM to process each brain.

Discussion

The key finding of this study is that the FDM algorithm provided superior anatomical correspondences for groupwise analysis of cerebral blood flow in elderly subjects. In these studies, the normalization methods were used to register the reference volume to the subject volume to carry anatomical labels to the individual. We demonstrate that FDM also improves normalization accuracy from the subject to the reference space, which is complementary to the previous results (18,19). Moreover, we compared more brain structures and evaluated the normalization accuracy across all subjects in a single, unified measure. Higher overlap ratios with FDM suggest that FDM can correct for anatomical variability between subjects with higher fidelity than SPM.

While high-dimensional normalization has been widely reported to provide more accurate alignment of anatomical structures between individuals, the impact of nonlinear alignment methods on voxel-based analyses of functional imaging data has been unclear. On the one hand, groupwise PET activation maps may be largely insensitive to the spatial normalization procedures used to create them (25). This insensitivity may be due to the limited spatial resolution of PET and its inherent functional variability. On the other hand, increased accuracy of spatial normalization was reported to result in a significant increase in the detection sensitivity of BOLD fMRI (19,28). Our findings suggest that the sensitivity of CASL pMRI, like that of fMRI, may increase due to high-dimensional transformation methods. These findings were pronounced when applied to pMRI analysis of elderly cognition groups, for whom anatomical variability may be dramatic due to the effects of healthy and pathological aging processes. We note that all image processing steps were identical for the SPM and FDM analyses except the spatial normalization procedures; this ensured that the difference observed is attributed to the normalization algorithm. However, the overall overlap ratios were lower (much lower in some regions) than the overlap ratios, indicating variability in the regional correspondence across subjects. But significant difference in the efficiency of normalization between healthy controls and subjects with disease was not observed in our data. However, further validation is required due to our low number of subjects. Whether any further improvement in accounting for inter-subject variability in FDM could improve the ability to detect the perfusion changes remains open. It depends on the relative degrees of functional variability and anatomical variability across subjects.

We used the 3D overlap ratio as our criterion for normalization accuracy. Previous comparisons were based on tissue probability maps (gray matter, white matter, and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF)) to measure the overall matching between the individual volume and the reference volume (17,25). While the tissue probability maps may provide complementary accuracy information to our region-based measures, we focused on matching finer anatomical regions due to their relevance to the study of dementia. Although the total information entropy measure (17) can be extended to account for finer anatomical structure labeling, we did not have access to fine-grained structure labels covering entire subject brains. Therefore, we focused on several biologically important regions for aging and dementia.

The strikingly larger cluster sizes resulting from FDM compared with SPM2, regardless of the effects of the threshold used and smoothing kernel, showed the superiority of FDM over the SPM2 on the sensitivity of pMRI comparison. Increasing the voxel-level threshold or smoothing kernel size may increase the cluster size, but not its statistical significance. Therefore the improved normalization accuracy from FDM is essential to ensure high sensitivity in the biostatistical analysis.

Decreased perfusion in the posterior cingulate gyrus in moderate to advanced AD is a consistent finding in a variety of neuroimaging studies (38,42,43). ASL studies including mild AD cases also reported hypoperfusion in the posterior cingulated regions (1,2). This repeated finding may be consistent with the known pattern of AD pathology, which is known to preferentially affect the posterior cingulate gyrus early in the disease course. The FDM results demonstrate that our AD subjects had significantly decreased perfusion in the posterior cingulate gyrus with a corrected cluster P-value of 0.0002 although our AD subjects are early ADs. However, SPM2 does not show a significant effect in this region. Inaccuracy in image normalization could introduce error into group comparisons. However, the posterior cingulate regions detected to be significant using FDM mainly fall within the overlap region of the posterior cingulate gyrus from the first study group. The errors introduced into group comparisons from the efficiency of image normalization between groups would introduce perfusion differences, which do not center on the overlap region. Therefore, the posterior cingulate gyrus regions from FDM could be hardly an artifact from normalization errors between groups. This suggests that FDM is beneficial for early CASL-based AD detection since FDM minimizes the anatomical variability between subject and reference volumes.

It is worth noting that the difference between SPM2 and FDM normalization appears large when the pMRI group comparison involves the AD subjects (MCIs vs. ADs; and normal controls vs. ADs). The pathology-related brains of AD subjects may require large deformations to align to the reference brain. The performance of FDM for anatomical variability between subjects improves sensitivity in biostatistics of pMRI. This indicates that FDM is useful in the elderly brain diseases or any diseases which lead to heteregenous atrophy of different brain structures.

The normalization package of the latest version of SPM (SPM5) reportedly uses a low-dimensional algorithm. Therefore, we expect SPM5 will yield a similar normalization performance as SPM2 when compared to FDM. Nevertheless, a quantitative comparison of FDM and the most advanced SPM method is warranted.

In conclusion, we conducted a quantitative comparison of normalization accuracy between SPM2 and FDM. The results showed that FDM improved normalization accuracy from subject to reference space in five brain structures and suggested that FDM can correct for anatomical variability between subjects with higher fidelity than SPM. Furthermore, we assessed the effects of normalization methods on the sensitivity of biostatistical analysis of CASL pMRI in elderly brains. The results indicated that improved normalization accuracy from FDM is essential to ensure high statistical sensitivity in the perfusion group analysis.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was supported by grants AG15928 and AG20098 from the National Institute on Aging, and by contracts N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, and N01-HC-15103 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

References

- 1.Alsop DC, Detre JA, Grossman M. Assessment of cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer's disease by spin-labeled magnetic resonance imaging. Annals of Neurology. 2000;47(1):93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson NA, Jahng G-H, Weiner MW, et al. Pattern of cerebral hypoperfusion in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment measured with arterial spin-labeling MR imaging: Initial experience. Radiology. 2005;234:851–859. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2343040197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalela JA, Alsop DC, Gonzalez-Atavales JB, Maldjian JA, Kasner SE, Detre JA. Magnetic resonance perfusion imaging in acute ischemic stroke using continuous arterial spin labeling. Stroke. 2000;31(3):680–687. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Detre JA, Alsop DC. Perfusion magnetic resonance imaging with continuous arterial spin labeling: methods and clinical applications in the central nervous system. Eur J Radiol. 1999;30(2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(99)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du AT, Jahng GH, Hayasaka S, et al. Hypoperfusion in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease by arterial spin labeling MRI. Neurology. 2006;67(7):1215–1220. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238163.71349.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf RL, Detre JA. Clinical neuroimaging using arterial spin-labeled perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4(3):346–359. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox PT, Perlmutter JS, Raichle ME. A stereotactic method of anatomical localization for positron emission tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985;9(1):141–153. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198501000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. New York: Thieme Medical; 1988. p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29(3):162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Worsley KJ, Poline J-B, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ. Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: A general linear approach. Human Brain Mapping. 1995;2:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woods RP, Grafton ST, Holmes CJ, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC. Automated image registration: I General methods and intrasubject, intramodality validation. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 1998;22:139–152. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199801000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen GE, Joshi SC, Miller MI. Volumetric transformation of brain anatomy. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1997;16(6):864–877. doi: 10.1109/42.650882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thirion JP. Image matching as a diffusion process: an analogy with Maxwell's demons. Med Image Anal. 1998;2(3):243–260. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(98)80022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen M. doctoral dissertation. Carnegie Mellon University; Oct, 1999. 3-D Deformable Registration Using a Statistical Atlas with Applications in Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoo T. Insight into image principles and practice for segmentation, registration, and image analysis. Wellesey, MA: AK Peters Ltd; 2004. p. 410. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ardekani BA, Guckemus S, Bachman A, Hoptman MJ, Wojtaszek M, Nierenberg J. Quantitative comparison of algorithms for inter-subject registration of 3D volumetric brain MRI scans. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;142(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins S, Evans AC, Collins DL, Whitesides S. Tuning and comparing spatial normalization methods. Med Image Anal. 2004;8(3):311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmichael OT, Aizenstein HA, Davis SW, et al. Atlas-based hippocampus segmentation in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2005;27(4):979–990. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu M, Carmichael O, Lopez-Garcia P, Carter CS, Aizenstein HJ. Quantitative comparison of AIR, SPM, and the fully deformable model for atlas-based segmentation of functional and structural MR images. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27(9):747–754. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins DL, Neelin P, Peters TM, Evans AC. Automatic 3D intersubject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18(2):192–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minoshima S, Koeppe RA, Frey KA, Kuhl DE. Anatomic standardization: linear scaling and nonlinear warping of functional brain images. J Nucl Med. 1994;35(9):1528–1537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersson JL, Thurfjell L. Implementation and validation of a fully automatic system for intra- and interindividual registration of PET brain scans. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1997;21(1):136–144. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199701000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry--the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11(6 Pt 1):805–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson PM, Woods RP, Mega MS, Toga AW. Mathematical/computational challenges in creating deformable and probabilistic atlases of the human brain. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;9(2):81–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200002)9:2<81::AID-HBM3>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crivello F, Schormann T, Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Roland PE, Zilles K, Mazoyer BM. Comparison of spatial normalization procedures and their impact on functional maps. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;16(4):228–250. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Senda M, Ishii K, Oda K, et al. Influence of ANOVA design and anatomical standardization on statistical mapping for PET activation. Neuroimage. 1998;8(3):283–301. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kjems U, Strother SC, Anderson J, Law I, Hansen LK. Enhancing the multivariate signal of [15O] water PET studies with a new nonlinear neuroanatomical registration algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1999;18(4):306–319. doi: 10.1109/42.768840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ardekani BA, Bachman AH, Strother SC, Fujibayashi Y, Yonekura Y. Impact of inter-subject registration on group analysis of fMRI data. International Congress Series. 2004;(1265):49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gee JC, Alsop DCKAG. Effect of spatial normalization of analysis of functional data. In: Hanson KM, editor. Medical imaging Proc SPIE 1997. Vol. 3044. 1997. pp. 550–560. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, Dekosky ST, et al. Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the cardiovascular health study cognitive. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1385–1389. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alsop DC, Detre JA. Multisection cerebral blood flow imaging with continous arterial spin labeling. Radiology. 1998;208:410–416. doi: 10.1148/radiology.208.2.9680569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gach HM, Dai W. Simple model of double adiabatic inversion (DAI) efficiency. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(4):941–946. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmes CJ, Hoge R, Collins L, Woods R, Toga AW, Evans AC. Enhancement of MR images using registration for signal averaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:324–333. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199803000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celsis P. Age-related cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment or preclinical Alzheimer's disease? Ann Med. 2000;32(1):6–14. doi: 10.3109/07853890008995904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kogure D, Matsuda H, Ohnishi T, Kumihiro T, Uno M, Takasaki M. Longitudinal evaluation of early Alzheimer disease using brain perfusion SPECT. J Nucl Med. 2000;41(7):1155–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visser PJ, Verhey FRJ, Hofman PAM, Scheltens P, Jolles J. Medial temporal lobe atrophy predicts Alzheimer's disease in patients with minor cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosur Psychiatry. 2002;72:491–497. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang C, Wahlund L-O, Svensson L, Winblad B, Julin P. Cingulate cortex hypoperfusion predicts Alzheimer's disease in mild cognitive impairment. Bio Med Central Neurology. 2002;2(9):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buxton RB, Frank LR, Wong EC, Siewert B, Warach S, Edelman RR. A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40:383–396. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen BH. Explaining psychological statistics. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. p. 351. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friston KJ, Holmes A, Poline JB, Price CJ, Frith CD. Detecting activations in PET and fMRI: levels of inference and power. Neuroimage. 1996;4(3 Pt 1):223–235. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alexander GE, Chen K, Pietrini P, Rapoport SI, Reiman EM. Longitudinal PET evaluation of cerebral metabolic decline in dementia: a potential outcome measure in Alzheimer's disease treatment studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:738–745. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonte FJ, Harris TS, Roney CA, Hynan LS. Differential diagnosis between Alzheimer's and frontotemporal disease by the posterior cingulate sign. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(5):771–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]