Abstract

Archaeological and palaeontological evidence from the Early Stone Age (ESA) documents parallel trends of brain expansion and technological elaboration in human evolution over a period of more than 2 Myr. However, the relationship between these defining trends remains controversial and poorly understood. Here, we present results from a positron emission tomography study of functional brain activation during experimental ESA (Oldowan and Acheulean) toolmaking by expert subjects. Together with a previous study of Oldowan toolmaking by novices, these results document increased demands for effective visuomotor coordination and hierarchical action organization in more advanced toolmaking. This includes an increased activation of ventral premotor and inferior parietal elements of the parietofrontal praxis circuits in both the hemispheres and of the right hemisphere homologue of Broca's area. The observed patterns of activation and of overlap with language circuits suggest that toolmaking and language share a basis in more general human capacities for complex, goal-directed action. The results are consistent with coevolutionary hypotheses linking the emergence of language, toolmaking, population-level functional lateralization and association cortex expansion in human evolution.

Keywords: brain, tool, positron emission tomography, Oldowan, Acheulean, Broca's area

1. Introduction

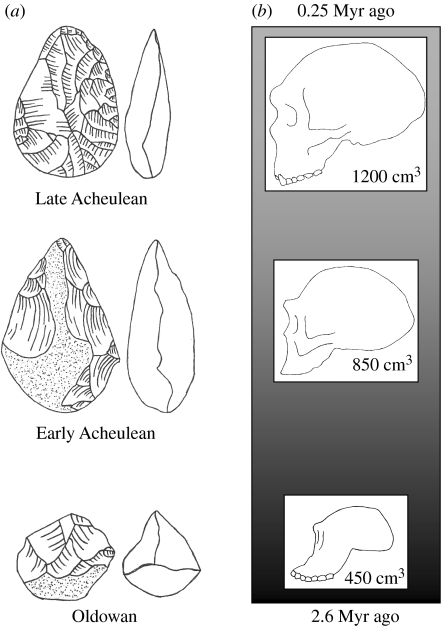

Human brains and technology have been coevolving for at least the past 2.6 Myr since the appearance of the first intentionally modified stone tools (Semaw et al. 1997). Roughly 90% of this time span, from 2.6 to 0.25 Myr ago, is encompassed by the Early Stone Age (ESA; generally known outside Africa as the Lower Palaeolithic). This period witnessed a technological progression from simple ‘Oldowan’ stone chips to skilfully shaped ‘Acheulean’ cutting tools, as well as a nearly threefold increase in hominin brain size (figure 1). These parallel trends of brain expansion and technological elaboration are defining features of human evolution, yet the relationship between them remains controversial and poorly understood (Gibson & Ingold 1993; Ambrose 2001; Wynn 2002; Stout 2006). This is largely due to a lack of information regarding the cognitive and neural foundations of technological behaviour. From this evolutionary perspective, understanding the brain bases of complex tool-use and toolmaking emerges as a key issue for cognitive neuroscience (Johnson-Frey 2003; Iriki 2005).

Figure 1.

Early Stone Age (a) technological and (b) biological change. Elements drawn after Klein (1999).

Ongoing research with macaques (Maravita & Iriki 2004) and humans (Frey et al. 2005; Johnson-Frey et al. 2005) has identified putatively homologous parietofrontal prehension circuits supporting simple, unimanual tool use in both the species. Building on this work, a recent fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) study of Oldowan toolmaking in technologically naive modern humans (Stout & Chaminade 2007) documented reliance on one such anterior parietal–ventral premotor grasp system as well as additional sensorimotor and posterior parietal activations related to the distinctive demands of this uniquely hominin skill. Of particular interest was the bilateral recruitment of human visual specializations (Orban et al. 2006) in the dorsal intraparietal sulcus (IPS). In contrast, there was no observed activation of prefrontal cortex (PFC).

These results suggest that evolved parietofrontal circuits enhancing sensorimotor adaptation, rather than higher level prefrontal action planning systems, were central to early ESA technological evolution. This is consistent with the fossil evidence of expanded posterior parietal lobes but relatively primitive prefrontal lobes in hominins leading up to the appearance of the first stone tools (Holloway et al. 2004). However, this study of novice toolmakers did not address expert performance. Subjects learned to detach sharp-edged stone flakes in a least-effort fashion, but did not replicate the well-controlled, systematic and productive flaking seen at many Oldowan sites (e.g. Semaw 2000; Delagnes & Roche 2005). Such skilled Oldowan flaking might hypothetically involve strategic elements and neural substrates not implicated in novice toolmaking. This is even more probable with respect to the more complex Acheulean toolmaking techniques that began to develop after ca 1.7 Myr ago.

Oldowan toolmaking involves the production of sharp-edged flakes by striking one stone (the core) with another (the hammerstone). Effective flake detachment minimally requires visuomotor coordination and evaluation of core morphology (e.g. angles, surfaces) so that forceful blows may reliably be directed to appropriate targets. Skilled flake production, in which many flakes are removed from a single core, potentially adds a strategic element because successive flake removals leave ‘scars’ which may be used to prospectively create and/or maintain favourable flaking surfaces. If such strategizing is important to skilled Oldowan toolmaking, one might expect an increased recruitment of prefrontal action planning and execution systems (Passingham & Sakai 2004; Ridderinkhof et al. 2004; Petrides 2005), including anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), in which activity is modulated by the complexity of motor planning tasks (Dagher et al. 1999). Expert familiarity with objects and actions involved in the toolmaking task might also be reflected in the activation of the left inferior parietal lobe (IPL), a region commonly activated in tasks involving familiar tools (Lewis 2006), including pantomime, action planning and action evaluation. The left posterior IPL in particular may be associated with the representation of stored motor programmes for familiar tool-use skills (Johnson-Frey et al. 2005). The activation of left posterior temporal cortex, commonly associated with semantic knowledge of tools and tool-use (Johnson-Frey et al. 2005; Lewis 2006), might be expected for similar reasons.

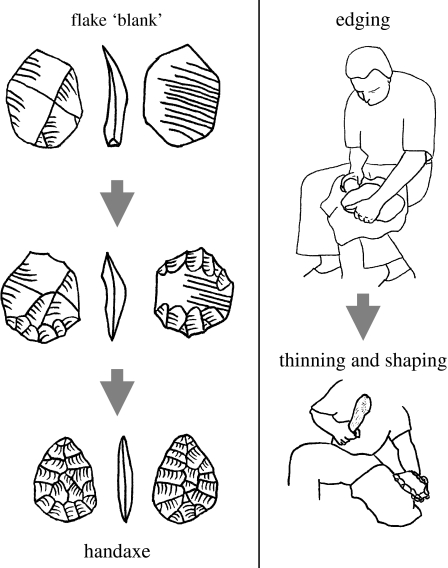

Putatively strategic task elements are greatly expanded in Acheulean toolmaking, which requires the intentional shaping of the core to achieve a predetermined form (figure 2). The prototypical Acheulean artefact is the so-called ‘hand axe’, a more-or-less symmetrical, teardrop-shaped tool well suited for butchery and other heavy duty cutting tasks (Schick & Toth 1993). Although initially quite crude, by the later ESA (less than 0.5 Myr ago) these tools achieved a level of refinement indicative of advanced toolmaking skills (Edwards 2001) and perhaps even of aesthetic concerns beyond the purely utilitarian. Such later Acheulean forms were the focus of the current study, providing maximum contrast with the Oldowan toolmaking task.

Figure 2.

Acheulean toolmaking. Elements drawn after Inizan et al. (1999).

One common Acheulean toolmaking method known from prehistory (Toth 2001) is the production of hand axes on large (greater than 20 cm) flake ‘blanks’ struck from boulder cores. Subsequent shaping of the tool involves three overlapping stages of flaking, as described in Stout et al. (2006). First, a relatively large, dense hammerstone is used to create a regular edge around the perimeter of the blank, centred between the two faces. This ‘roughing out’ stage serves to create viable angles and surfaces for the subsequent removal of large thinning flakes. ‘Primary thinning and shaping’ then aims to reduce the overall thickness of the piece and to begin imposing the desired symmetrical shape. Thinning flakes must be relatively thin and long, travelling at least halfway across the piece in order to reduce thickness in the centre. Prior to each thinning flake removal, intensive, light flaking is done along the perimeter with a smaller hammerstone to steepen, regularize and strengthen the edge. Thinning flakes are then struck using either the hammerstone or a baton of antler, bone or wood, which acts as a ‘soft’ hammer facilitating the removal of thin flakes. The baton is most extensively used in the final stage, ‘secondary thinning and shaping’, which involves more intensive edge preparation through flaking and abrasion/grinding in order to ensure highly controlled flake removals that establish a thin, symmetrical tool with straight and regular edges.

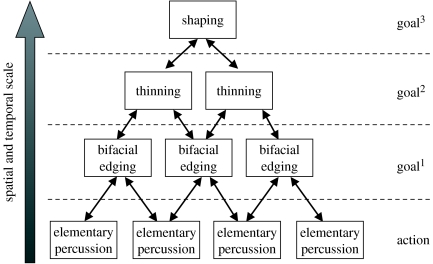

From a toolmaker's perspective, later Acheulean hand axe making seems much more demanding than Oldowan flaking, requiring (i) greater motor skill and practical understanding of stone fracture (i.e. influence of angles, edges and surfaces), (ii) more elaborate planning including the subordination of immediate goals to long-term objectives (figure 3), and (iii) an increased number of special purpose knapping tools and technical operations. In comparison with Oldowan flaking, later Acheulean toolmaking might thus be expected to produce increased activity in (i) parietofrontal prehension circuits involved in manual perceptual–motor coordination (Rizzolatti et al. 1998; Maravita & Iriki 2004; Frey et al. 2005), (ii) prefrontal action planning systems potentially including ACC and dlPFC (Dagher et al. 1999; Passingham & Sakai 2004; Petrides 2005), and (iii) left posterior parietal and temporal cortices associated with semantic representations for the use of familiar tools (Johnson-Frey et al. 2005).

Figure 3.

Multi-level organization of Acheulean toolmaking.

In order to test these predictions, we conducted a second FDG-PET study of ESA toolmaking by expert subjects. Unfortunately, stone toolmaking is not a common skill in the modern world, and hence recruitment of expert subjects presents a unique challenge. The current study included three professional archaeologists, each with more than 10 years toolmaking experience. Despite this limited sample size, the FDG-PET procedure yielded a large signal to noise ratio sufficient for statistical analysis. Following the methods established in the previous study, brain activation data were collected for two toolmaking tasks: Oldowan flake production and Acheulean hand axe making. As in the previous study, toolmaking tasks were contrasted with a control task consisting of bimanual percussion without flake production. Results from the current study were also contrasted with novice (post-practice) data from the previous study.

2. Material and methods

(a) Experimental subjects

Three healthy, right-handed subjects (one female) between 30 and 55 years of age participated in the study. The subjects were professional archaeologists with more than 10 years stone toolmaking experience and already familiar with Oldowan and Late Acheulean technologies. All subjects gave informed written consent. The study was performed in accordance with the guidelines from the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at Indiana University, Bloomington.

(b) Experimental tasks

Each subject performed three experimental tasks.

Control. Subjects were instructed to forcefully strike together cobbles without attempting to produce flakes. They were given no specific instructions as to the manner in which to strike the stones together. This control was designed to match gross visuomotor elements of the experimental task without involving the elements of percussive accuracy, core rotation and support distinctive to stone toolmaking.

Oldowan toolmaking. On a subsequent day, the subjects were instructed to produce ‘Oldowan-style’ flakes from the cobbles from the cart. They were instructed to focus on the production of flakes that would be ‘useful for cutting’, rather than on the shape of the residual cores. No further instructions regarding toolmaking methods were given.

Acheulean toolmaking. On a third day, the subjects were instructed to make one or more ‘typical Late Acheulean’ hand axes, as time permitted. Obsidian flake blanks were provided on the cart. The relatively large blanks were supported on the left thigh rather than held in the hand (figure 2). Nevertheless, the left hand played a key role in manipulating, orienting and stabilizing the blank. Stone working tools are highly personal items to which individuals become accustomed, and subjects were allowed to use their own tools, including hammerstones, antler batons and protective pads for the thigh. Tools were standardized in the sense that each subject used those they were familiar with, rather than each using the same (unfamiliar) tools.

The subjects performed all tasks comfortably seated on a chair with an array of stone raw materials available within easy reach on a cart to their left. The selection of materials from those provided was a component of all tasks. Cobbles were collected at a gravel quarry in Martinsville, IN, and included a range of sizes, shapes and materials, primarily limestone, quartzite and variously metamorphosed basalt (e.g. greenstone). Obsidian blanks had previously been struck from a discoidal boulder core, but were otherwise unmodified.

(c) Functional imaging

The use of the relatively slowly decaying radiological tracer 18fluoro-2-deoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) allowed for naturalistic task performance outside the confines of the scanner. A venous catheter to administer the tracer was inserted in a vein of the foot. Thirty seconds after the condition started, a 10-mCi bolus of [18F]FDG, produced on-site, was injected. Each task was performed for 40 min, well past the tracer uptake period, and was followed by a 45 min PET scanning session.

Whole brain FDG-PET imaging was performed using an ECAT 951/31 PET scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Inc., Hoffman Estates, IL) at the Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Radiology. Sixty-three continuous 128×128 transaxial images with a slice thickness of 2.43 mm and an in-plane axial resolution of 2.06 mm (field of view: 263.68×263.68×153.09 mm3) were acquired simultaneously with collimating septa retracted operating in a three-dimensional mode. The correction for attenuation was made using a transmission scan collected at the end of each session.

(d) Image analysis

Images were reconstructed and analysed using standard SPM2 procedures. For each subject, images were realigned to the control condition scan, normalized into the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) stereotaxic space and smoothed using a 6 mm full-width at half-maximum Gaussian filter convolution. A population main effect model with three conditions (control condition, Oldowan toolmaking and Acheulean toolmaking) from the three subjects was selected, leaving 4 d.f. from nine images. Linear contrasts assessing differences between toolmaking conditions and the control condition were used to create statistical parametric maps. Coordinates are expressed in terms of the MNI template.

In a previous experiment, naive subjects practiced Oldowan toolmaking but did not reach an expert level of performance (details in Stout & Chaminade 2007). A second analysis was performed to investigate the interaction between expertise and toolmaking. A 2×2 factorial design was used, with two within-subject conditions (Oldowan toolmaking and control) and two populations (experts, n=3 and novices from the previous experiment, n=6), leaving 15 d.f. from 18 images. In addition to linear contrasts assessing differences between toolmaking conditions and the control condition in both the populations, we focused on the interaction between the two factors. The interaction contrast ((experts, Oldowan–experts, control)–(novices, Oldowan–novices, control)) revealed areas significantly increased in experts during Oldowan toolmaking compared to control but not in novices during Oldowan toolmaking compared to control. Inclusive masking with the contrast experts, Oldowan–experts, control (p<0.01) was used to ensure directionality of the interaction. The reverse interaction, masked with novices, Oldowan–novices, control was used to reveal areas significantly increased in novices doing Oldowan tools compared to control but not in experts doing Oldowan tools compared to control. All contrasts were thresholded at p<0.001 uncorrected and extent k>5. Reported contrast estimates were recorded at the statistically most significant voxel of the clusters.

(e) Artefact analysis

All artefacts produced during recording sessions were collected. Oldowan artefacts (flakes, cores and fragments) were analysed with respect to typological classification, frequency, technological characteristics, mass, linear dimensions and morphology. Hand axes were analysed with respect to typological classification (i.e. shape), mass and linear dimensions. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS.

3. Results

(a) Toolmaking performance

All subjects succeeded in producing characteristic Oldowan and Late Acheulean artefacts. As in actual archaeological assemblages, performance was evaluated on physical characteristics of the artefacts produced. Expert Oldowan toolmaking differed from that of novices (Stout & Chaminade 2007) in the greater number of cores (t′=−5.55; d.f.=4.11; p=0.062) modified during the given time, the greater number of flakes and fragments produced (t′=−4.55; d.f.=2.68; p=0.025), and the greater absolute length (p<0.05) and relative elongation (p<0.05) of flakes produced. Experts were also much more likely to use scars left by previous flakes as a striking surface for further flake removals, as evidenced by the distribution of original, weathered cobble surface (‘cortex’) on flakes (Pearson's Χ52=42.13, p<0.001). As a result of these differences, the core types (e.g. ‘chopper’, ‘discoid’, ‘polyhedron’; Leakey 1971) produced by experts were more similar to those found at actual Oldowan sites than was the case with novices.

Hand axes produced were also typical of those that might be found in the Late Acheulean, less than 500 kyr ago. Subjects each produced from 1 to 3 hand axes, as shown in table 1. The uniformly high breadth/thickness ratios obtained reflect a high level of refinement.

Table 1.

Experimental hand axe attributes.

| subject | hand axes produced | mass (g) | length (mm) | breadth (mm) | thickness (mm) | breadth/thickness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1960 | 250 | 140 | 56 | 2.50 |

| 2 | 1 | 1174 | 223 | 133 | 45 | 2.96 |

| 3 | 3 | 549 | 160 | 106 | 35 | 3.03 |

| 482 | 147 | 112 | 33 | 3.39 | ||

| 792 | 192 | 137 | 39 | 3.51 |

(b) PET results

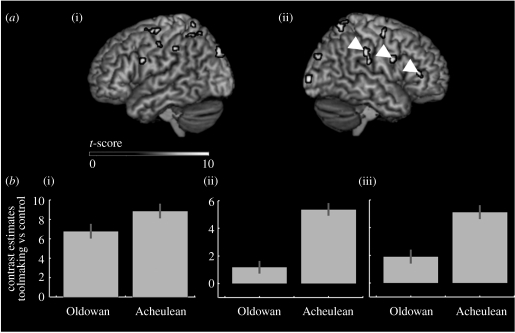

Table 2 gives results for the two contrasts of interest: Oldowan toolmaking versus control, and Acheulean toolmaking versus control. Bilateral parietal clusters, in the superior and inferior lobules and in the IPS, overlapped in the two contrasts, as did most of the early visual activities in the posterior occipital cortices (Brodmann areas (BA) 17 and 18). In contrast, differences were found in the higher order visual areas of the occipital (BA 19) and temporal cortices and in the frontal cortex. A large right inferior temporal gyrus activation was found for Oldowan toolmaking. Only in the left hemisphere (LH) lateral and ventral precentral gyrii (BA 6) did the activity for the two toolmaking tasks overlap. Oldowan toolmaking was additionally associated with activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, while Acheulean toolmaking yielded a number of additional clusters in the dorsal precentral (BA 6) gyrus bilaterally, particularly strong in the right hemisphere (RH), as well as in the RH ventral precentral (BA 6) and inferior prefrontal (BA 45) cortices. Contrast estimates for the two toolmaking tasks in the RH supramarginal, ventral precentral and inferior prefrontal gyrii are illustrated in figure 4.

Table 2.

Location of activated clusters found in contrasts between Oldowan toolmaking and control and between Acheulean toolmaking and control by expert tool knappers. (p<0.001 uncorrected, k>5, n=3.Clusters are organized by cortical regions and ordered by decreasing z-coordinate within each region. Blank spaces indicate a lack of significant activation. Coordinates are relative to the Montreal Neurological Institute standard template brain. BA, Brodmann area.)

| location | BA | Oldowan-control | Acheulean-control | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | t-score | x | y | z | t-score | |||

| frontal cortex | ||||||||||

| right | dorsal precentral gyrus | 6 | 34 | −8 | 58 | 46.33 | ||||

| left | dorsal precentral gyrus | 6 | −24 | −8 | 58 | 17.27 | ||||

| left | lateral precentral gyrus | 4/6 | −46 | −16 | 44 | 14.16 | −44 | −14 | 46 | 17.16 |

| left | ventral precentral gyrus | 6 | −52 | 6 | 28 | 9.72 | −52 | 6 | 28 | 12.24 |

| right | ventral precentral gyrus | 6 | 60 | 2 | 26 | 19.68 | ||||

| right | inferior prefrontal gyrus | 45 | 48 | 34 | 10 | 17.08 | ||||

| left | orbital gyrus | 11 | −24 | 32 | −22 | 15.1 | ||||

| parietal cortex | ||||||||||

| left | superior parietal lobule | 5 | −14 | −54 | 70 | 14.46 | −14 | −54 | 70 | 12.59 |

| right | superior parietal lobule | 7 | 24 | −60 | 66 | 11.74 | 22 | −62 | 68 | 13.42 |

| right | intraparietal sulcus | 7/40 | 34 | −52 | 60 | 15.34 | 34 | −52 | 60 | 12.32 |

| left | intraparietal sulcus | 7/40 | −28 | −48 | 52 | 12.37 | −28 | −48 | 52 | 13.81 |

| left | supramarginal gyrus | 40 | −48 | −32 | 40 | 8.67 | −48 | −32 | 42 | 10.40 |

| right | supramarginal gyrus | 40 | 58 | −30 | 36 | 14.98 | 58 | −30 | 36 | 19.57 |

| temporal cortex | ||||||||||

| right | inferior temporal gyrus | 20/21/37 | 52 | −50 | −10 | 30.49 | ||||

| occipital cortex | ||||||||||

| left | parieto-occipital sulcus | 19/7 | −22 | −62 | 58 | 9.62 | ||||

| left | parieto-occipital sulcus | 19/7 | 30 | −88 | 44 | 12.07 | ||||

| left | superior occipital gyrus | 19 | −16 | −86 | 38 | 34.22 | −16 | −86 | 38 | 62.34 |

| right | middle occipital gyrus | 19 | 32 | −66 | 32 | 10.9 | ||||

| right | middle occipital gyrus | 18 | 22 | −88 | 28 | 10.54 | 20 | −88 | 30 | 9.21 |

| cuneus | 18 | 4 | −86 | 24 | 21.59 | 4 | −86 | 24 | 19.42 | |

| right | calcarine sulcus | 17 | 18 | −96 | 2 | 28.65 | 18 | −96 | 2 | 18.09 |

| left | lingual gyrus | 17 | −12 | −84 | −6 | 24.98 | −12 | −84 | −6 | 44.93 |

| right | lingual gyrus | 19 | 30 | −68 | −10 | 31.65 | ||||

| right | fusiform gyrus | 18 | 30 | −76 | −16 | 26.18 | 30 | −76 | −16 | 14.15 |

Figure 4.

Main effects of expert toolmaking. (a) Lateral renders of brain activation ((i) left and (ii) right) during expert Acheulean toolmaking (see table 2). (b) Estimates for the contrasts Oldowan versus control and Acheulean versus control at the peak of the (i) supramarginal, (ii) ventral precentral, and (iii) inferior frontal clusters in the right hemisphere (white arrows on the right hemisphere render).

The second analysis compared the brain activity during Oldowan toolmaking and the control conditions in the experts scanned here to the brain activity in the same tasks scanned in toolmaking novices after they received some training (Stout & Chaminade 2007). The experiments with experts and with novices contained the same conditions, allowing their inclusion in a single multi-group analysis. Trained novices and experts differed in the expertise in toolmaking, but both had prior exposure to Oldowan toolmaking, ruling out a response to novelty and surprise in novices. A network of occipital, parietal and frontal areas was found in the contrasts between Oldowan toolmaking and control for the two populations, listed in the electronic supplementary material, table 1. Most occipital activations overlapped, with the exceptions of some ventral clusters (right fusiform and left lingual gyrii) and the right parieto-occipital sulcus. In the frontal cortex, there were more activated clusters in novices than in experts, though the left ventral precentral gyrus cluster was reported in table 1 for Oldowan toolmaking. There was a posterior shift in one of the superior parietal clusters (from x, y, z=24, −46, 60 in novices to 24, −72, 58 in experts) as well as a bilateral supramarginal gyrus (SMG) activity for experts only (BA 40).

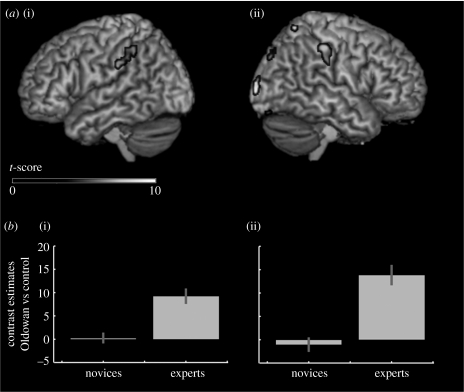

An interaction contrast was used to report areas involved in Oldowan toolmaking in experts only (table 3), revealing activity in the RH occipital cortex and superior parietal lobule and in the SMG bilaterally. These later inferior parietal clusters of activity are shown in figure 5, with contrast estimates showing a significant increase in activity during Oldowan toolmaking compared to control in experts, but not in novices. No clusters survived in the reverse interaction, indicating that there were no brain regions more active in Oldowan toolmaking versus control in novices but not in experts.

Table 3.

Location of activated clusters in the interaction between toolmaking and expertise. (The interaction contrast (experts, Oldowan–experts, control)–(novices, Oldowan–novices, control), p<0.001 uncorrected, k>5, was inclusively masked with the contrast experts, Oldowan–experts, control (p<0.01) to ensure directionality. Coordinates are relative to the Montreal Neurological Institute standard template brain. BA, Brodmann area.)

| location | BA | x | y | z | t-score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parietal cortex | ||||||

| right | superior parietal lobule | 7 | 28 | −60 | 68 | 11.45 |

| right | supramarginal gyrus | 40 | 56 | −30 | 48 | 9.18 |

| left | supramarginal gyrus | 40 | −56 | −28 | 30 | 7.90 |

| occipital cortex | ||||||

| right | calcarine sulcus | 17 | 14 | −100 | 6 | 16.25 |

| right | middle occipital gyrus | 19 | 28 | −84 | 38 | 8.37 |

| right | lingual gyrus | 18 | 16 | −80 | −12 | 8.64 |

Figure 5.

Interaction between expertise and toolmaking. (a) Lateral renders of brain activation ((i) left and (ii) right) during expert Oldowan toolmaking (see table 3). (b) Estimates for the contrast Oldowan versus control in novice and expert toolmakers at the peak of the (i) left and (ii) right supramarginal clusters.

4. Discussion

Functional imaging research with modern humans cannot directly reveal the cognitive capacities or neural organization of extinct hominin species, but can clarify the relative demands of specific, evolutionarily significant behaviours. Used in conjunction with archaeological (Ambrose 2001; Wynn 2002), fossil (Holloway et al. 2004) and comparative (Passingham 1998; Rilling 2006) evidence, such information helps to constrain hypotheses about human cognitive and brain evolution. The results of the current study provide evidence of increased sensorimotor and cognitive demands related to the changing nature of expert performance (cf. Kelly & Garavan 2005) and to the complexity of toolmaking methods, and suggest important relationships between ESA technological change and evolving hominin brain size, functional lateralization and language capacities.

(a) Expert Oldowan toolmaking

As expected, expertise was associated with increased IPL activation during Oldowan toolmaking. However, contrary to expectation, this activation was strongly bilateral. This was surprising given the substantial imaging evidence of LH dominance for tasks involving familiar tools, regardless of the hand involved (Lewis 2006), as well as the strong association of ideomotor apraxia with lesions of the LH (Johnson-Frey 2004). Indeed, the left IPL activation is commonly reported for tasks involving manipulable objects and fine finger movements (Grezes & Decety 2001; Lewis 2006), and is thought to reflect a role in the visuospatial coding of moving limbs (i.e. the ‘body schema’; Chaminade et al. 2005) and/or storage of internal models for planning object-related movements (i.e. ‘action schemas’; Buxbaum et al. 2005).

Stored tool-use action schemas could engage the posterior regions of IPL (Johnson-Frey et al. 2005), whereas an anterior part would respond to action possibilities relative to tools (Kellenbach et al. 2003). Increased left IPL recruitment during expert Oldowan toolmaking is located in this more anterior region. This activation clearly relates to greater task familiarity in experts, and may reflect reliance on visuospatial body schemas that incorporate (Maravita & Iriki 2004) the handheld core and hammerstone. It would also be consistent with the hypothesis that regions adjoining human anterior IPS are involved in the storage of visuospatial properties associated with tool manipulation (Johnson-Frey et al. 2005). Combined with the observed right superior parietal lobule activity and a lack of any significant increase in the temporal cortex activity, these results indicate that expert Oldowan toolmaking performance depends more upon enhanced sensorimotor representations of the tool+body system than upon stored action semantics of the kind recruited by normal subjects planning the use of everyday tools (Johnson-Frey et al. 2005).

The right SMG activation in expert Oldowan toolmaking, although unexpected, most probably relates to the naturalistic task design. LH dominance is generally less pronounced during actual tool-use action execution than during more ‘conceptual’ imagery or planning tasks (Lewis 2006), and this has been reported for SMG specifically (Johnson-Frey et al. 2005). Bilateral SMG activation in the current study is thus consistent with the conclusion that expert performance is supported by an enhanced knowledge of the action properties of the tool+body system, rather than semantic knowledge about appropriate patterns of tool use. Bilateral activation is also likely to reflect a manual laterality effect similar to that seen in primary motor and sensory cortices, with right SMG contributing to the important action of the left hand supporting and orienting the core. This initially appears contrary to the well-documented phenomenon of motor equivalence seen in studies of handwriting (Rijntjes et al. 1999; Wing 2000) in which secondary sensorimotor cortices for the dominant hand are activated regardless of the effector used (e.g. toe, non-dominant hand). However, the role of the non-dominant hand in Oldowan toolmaking is not simply to execute gestures more typically done with the dominant hand but rather to properly position and support the core to receive the action of the dominant hand. The task is inherently bimanual, with distinct but complementary roles for the two hands.

A similar bimanual organization may be seen in many naturalistic human tool-using actions, such as sweeping, shovelling, threading a needle, striking a match or cutting paper with scissors, in which the non-dominant hand provides a steady spatial ‘frame’ for the higher frequency action of the dominant hand (MacNeilage et al. 1984; Guiard 1987). This characteristic division of labour probably reflects hemispheric specializations, with the stable support role of the left hand mapping onto well-known RH specializations for visuospatial processing, particularly at larger spatio-temporal scales (Gazzaniga 2000), and specifically including the activation of right SMG in visuospatial decision making (Stephan et al. 2003).

That bilateral SMG activation emerges in expert compared to novice toolmakers suggests that proper bimanual coordination, and particularly the left-hand support role, develops only after substantial practice. Novices instead appear focused on the more rapid percussive movements of the right hand, supported by LH parietofrontal prehension circuits. This different approach to the task probably explains major diff-erences in the performance of novices and experts. In comparison to novices, expert toolmakers were able to remove more and larger flakes from cores, and thus to generate heavily worked artefacts similar to those found at actual Oldowan sites. Larger, longer flakes travel further across core surfaces and leave relatively flat scars and acute angles on the core rather than the rounded edges typical of novice performance (Stout & Chaminade 2007). Consistent success in large flake detachment thus tends to produce advantageous morphology for further flake removals without the need for explicit and detailed planning by the toolmaker.

It had been hypothesized that such action sequences might involve a strategic element similar to that assessed by neuropsychological tests of motor planning (Dagher et al. 1999), and supported by similar prefrontal action planning and execution systems. This does not appear to be the case (table 3; electronic supplementary material, table 1). The current results instead support the idea that expert Oldowan toolmaking is enabled by greater sensorimotor control for effective flake detachment, supported by enhanced representations of the body+tool system and particularly of the larger scale spatio-temporal ‘frame’ provided by the RH–left-hand system. This is consistent with ethnographic accounts emphasizing the perceptual–motor foundations of many strategic regularities in stone toolmaking action organization (Stout 2002; Roux & David 2005).

(b) Late Acheulean toolmaking

The most striking result of the comparison between expert Oldowan and Late Acheulean toolmaking was an increase in the RH activity, including both SMG and new clusters in the right ventral premotor cortex (PMv, BA 6) and the inferior prefrontal gyrus (BA 45) (table 2, figure 5). This probably reflects an increasingly critical role for the RH–left-hand system in hand axe production as well as the involvement of more complex and protracted technical action sequences (cf. Hartmann et al. 2005). The increased right SMG activation extends the trend seen in expert Oldowan knapping and is best interpreted as reflecting further increases in the importance of visuospatial representations of the tool+body system in this task. Similarly, the novel activation of the right PMv may be attributed to increased motor demands relating to the manipulation, support and precise orientation of the larger Acheulean hand axe. Precise and forceful left-hand grips become increasingly critical as the piece is thinned in order to absorb shock and prevent accidental breakage, a concern that is much less salient in Oldowan knapping.

The activation of right inferior PFC (BA 45) during Acheulean toolmaking is of particular interest because PFC lies at the top of the brain's sensory and motor hierarchies (Passingham et al. 2000) and plays a central role in coordinating flexible, goal-directed behaviour (Ridderinkhof et al. 2004). Thus, PFC activation during hand axe production probably reflects greater demands for complex action regulation in this task. Ventrolateral PFC (vlPFC) in particular (including BA 45) seems to be involved in associating perceptual cues with the actions or choices they specify (Passingham et al. 2000), particularly when these actions are subordinate elements within ongoing, hierarchically structured action sequences (Koechlin & Jubault 2006). This underlying function may help explain the apparent overlap of language and praxis circuits in the inferior prefrontal gyrus. It is also consistent with the distinctive technical requirements of hand axe making, which include the skilful coordination of perception and action in pursuit of higher order goals (figure 3). In contrast, hypothesized dorsolateral PFC and ACC ‘action planning circuit’ activation was not observed. Dorsolateral PFC has been associated with the prospective (Passingham & Sakai 2004) monitoring and manipulation of information within working memory, and is commonly activated in tasks that separate planning from execution (e.g. Dagher et al. 1999; Johnson-Frey et al. 2005). The activation of ventrolateral, but not dorsolateral, PFC indicates that Acheulean toolmaking is distinguished by cognitive demands for the coordination of ongoing, hierarchically organized action sequences rather than the internal rehearsal and evaluation of action plans.

The localization of vlPFC activation to RH probably reflects demands for such action coordination that are particular to the left-hand core support and manipulation aspect of the task. This is consistent with the general task structure of stone knapping in which the RH/left-hand system provides goal-directed contextual ‘frames’ modulating the functionality of relatively rapid, and repetitive percussive actions by the LH–right-hand system. Parietofrontal (inferior parietal–ventral premotor) praxis circuits are activated bilaterally; however, increased requirements for cognitive control in the RH–left-hand system specifically may explain the exclusive activation of right vlPFC. Such localization of cognitive control to the same hemisphere as task execution has previously been reported in a visuospatial decision task (Stephan et al. 2003).

As in Oldowan knapping, lateralized patterns of brain activation and manual task organization probably relate to hemispheric specializations. For example, the right vlPFC is thought to play a dominant role in response inhibition and task-set switching (Aron et al. 2004). These abilities are critical to successful hand axe production, which involves frequent and highly flexible shifts between different technical operations and goals (e.g. platform preparation, bifacial edging, thinning) as well as the continual rejection of immediately attractive opportunities in favour of actions serving longer term objectives. Perhaps for similar reasons, lesion studies indicate an important RH contribution to the successful completion of multi-step mechanical problems (Hartmann et al. 2005). The increasingly anterior and RH-dominant frontal activation during Late Acheulean toolmaking reflects the more complex, multi-level structure of the task (figure 3), which includes the flexible iteration of multi-step processes in the context of larger scale technical goals. This characterization further invites comparison with the hierarchy of phonological-, syntactic-, semantic- and discourse-level processing that is characteristic of human linguistic behaviour (Hagoort 2005; Rose 2006).

(c) Tools, language and laterality in human evolution

Hypotheses linking language and tool-use have typically focused on the LH and its contributions to rapid, sequential and hierarchically organized behaviour (e.g. Greenfield 1991; Corballis 2003). This reflects a widespread perception of LH dominance for both language and praxis. However, it is well known that the RH plays an important role in language processing, particularly with respect to larger scale phenomena such as metaphor, figurative language, connotative meaning, prosody and discourse comprehension (Bookheimer 2002). Similarly, it is becoming apparent that the RH contributes substantially to elements of perception and action on larger spatio-temporal scales, including perceptual grouping (Gazzaniga 2000), task-set switching and inhibition (Aron et al. 2004), decision making in ambiguous situations (Goel et al. 2007), and naturalistic tasks involving multiple steps and objects (Hartmann et al. 2005). Bilateral activations observed during ESA toolmaking reflect multiple levels of overlap with cortical language circuits and suggest potential evolutionary interactions.

The anterior premotor cortex shares important functional and connectional characteristics with posterior PFC (Petrides 2005) and appears to play a role in phonological processing (Bookheimer 2002; Hagoort 2005). The activation of left anterior PMv during novice (Stout & Chaminade 2007) and expert Oldowan knapping corroborates the existing evidence of overlap between manual praxis and language processing (Hamzei et al. 2003; Rizzolatti & Craighero 2004), and may reflect an underlying role for this region in sensorimotor unification (Hagoort 2005) and conditional response selection (Petrides 2005) across modalities. Overlapping phonological and manual control in PMv is consistent with motor hypotheses of language origins linking manual coordination with evolving capacities for speech production (Kimura 1979; MacNeilage et al. 1984; Lieberman 2002). The specific recruitment of this region during Oldowan knapping provides a direct connection with evidence of hominin toolmaking skills going back 2.6 Myr. This suggests an alternative or addition to the emphasis placed on intransitive gestures and manual proto-language in many recent evolutionary scenarios (e.g. Rizzolatti & Arbib 1998; Corballis 2003), insofar as selection on toolmaking ability could also have indirectly contributed to the enhanced articulatory control so central to human language evolution (Studdert-Kennedy & Goldstein 2003).

Brain activation during hand axe making further indicates reliance on increasingly anterior and right lateralized PFC in a region also associated with discourse-level prosodic and contextual language processing (Bookheimer 2002). It is likely that the common denominator in these technical and linguistic tasks is their requirement for the coordination of behavioural elements into hierarchically structured sequences (Greenfield 1991; Koechlin & Jubault 2006) on the basis of contextual information integrated over relatively long time spans (cf. Bookheimer 2002). Archaeological evidence of ESA technological change thus traces a trajectory of ever more skill-intensive, bimanual toolmaking methods that overlap functionally and anatomically with important elements of the human faculty for language. This trend further coincides with the emergence of population-level manual lateralization (Steele & Uomini 2005) and the dramatic expansion of prefrontal and parieto-temporal association cortices (Holloway et al. 2004; Rilling 2006). Such correlations cannot demonstrate the direction of evolutionary cause and effect, but do suggest important interactions.

(d) Conclusions

Results presented here provide further evidence of the value of the archaeological record of technological change in understanding human cognitive evolution (Wynn 2002). More specifically, they document a trend of increasingly sophisticated hominin engagement with materials in ESA toolmaking, supported by neurally based capacities for effective visuomotor coordination and hierarchical action organization. Neural circuits supporting ESA toolmaking partially overlap with language circuits, strongly suggesting that these behaviours share a foundation in more general human capacities for complex, goal-directed action and are likely to have evolved in a mutually reinforcing way. These trends and relationships are consistent with archaeological, palaeontological and comparative evidence of emerging population-level functional lateralization and association cortex expansion in human evolution.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Colin Renfrew, Chris Frith and Lambros Malfouris for organizing the Sapient Mind conference, and all the participants for their lively and helpful discussion. We are particularly grateful to Scott Frey for his comments on a draft of this paper (although all remaining errors are ours alone) and to Kevin Perry and Susan Geiger of the Indiana University PET Imaging Center. Funding was provided by the Stone Age Institute.

Supplementary Material

Location of activated clusters found in contrasts between Oldowan toolmaking and control

References

- Ambrose S. Paleolithic technology and human evolution. Science. 2001;291:1748–1753. doi: 10.1126/science.1059487. doi:10.1126/science.1059487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron A.A, Robbins T.W, Poldrack R.A. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2004;8:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.010. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookheimer S. Functional MRI of language: new approaches to understanding the cortical organization of semantic processing. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;25:151–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142946. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum L.J, Johnson-Frey S.H, Bartlett-Williams M. Deficient internal models for planning hand–object interactions in apraxia. Neuropsychologica. 2005;43:917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.09.006. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaminade T, Meltzoff A, Decety J. An fMRI study of imitation: action representation and body schema. Neuropsychologica. 2005;43:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.04.026. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corballis M.C. From mouth to hand: gesture, speech, and the evolution of right handedness. Behav. Brain. Sci. 2003;26:199–260. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x03000062. doi:10.1017/S0140525X03000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagher A, Owen A.M, Boecker H, Brooks D.J. Mapping the network for planning: a correlational PET activation study with the Tower of London task. Brain. 1999;122:1973–1987. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.10.1973. doi:10.1093/brain/122.10.1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delagnes A, Roche H. Late Pliocene hominid knapping skills: the case of Lokalalei 2C, West Turkana, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 2005;48:435–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.12.005. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S.W. A modern knapper's assessment of the technical skills of the Late Acheulean biface workers at Kalambo Falls. In: Clark J.D, editor. Kalambo Falls prehistoric site. The earlier cultures: Middle and Earlier Stone Age. vol. 3. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. pp. 605–611. [Google Scholar]

- Frey S.H, Vinton D, Norlund R, Grafton S.T. Cortical topography of human anterior intraparietal cortex active during visually guided grasping. Cogn. Brain Res. 2005;23:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.11.010. doi:10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaniga M.S. Cerebral specialization and interhemispheric communication: does the corpus callosum enable the human condition? Brain. 2000;123:1293–1326. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.7.1293. doi:10.1093/brain/123.7.1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson K.R, Ingold T. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1993. Tools, language and cognition in human evolution. [Google Scholar]

- Goel V, Tierney M, Sheesley L, Bartolo A, Vartanian O, Grafman J. Hemispheric specialization in human prefrontal cortex for resolving certain and uncertain inferences. Cereb. Cortex. 2007;17:2245–2250. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl132. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhl132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield P.M. Language, tools, and brain: the development and evolution of hierarchically organized sequential behavior. Behav. Brain Sci. 1991;14:531–595. [Google Scholar]

- Grezes J, Decety J. Functional anatomy of execution, mental simulation, observation, and verb generation of action: a meta-analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2001;12:1–19. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200101)12:1<1::AID-HBM10>3.0.CO;2-V. doi:10.1002/1097-0193(200101)12:1<1::AID-HBM10>3.0.CO;2-V [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiard Y. Asymmetric division of labor in human skilled bimanual action: the kinematic chain as a model. J. Motor Behav. 1987;19:486–517. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1987.10735426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagoort P. On Broca, brain, and binding: a new framework. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005;9:416–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.07.004. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamzei F, Rijntjes M, Dettmers C, Glauche V, Weiller C, Buchel C. The human action recognition system and its relationship to Broca's area: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2003;19:637–644. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00087-9. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00087-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann K, Goldenberg G, Daumuller M, Hermsdorfer J. It takes the whole brain to make a cup of coffee: the neuropsychology of naturalistic actions involving technical devices. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:625–637. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.07.015. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway R, Broadfield D, Yuan M. Brain endocasts—the paleoneurological evidence. vol. 3. Wiley-Liss; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. The human fossil record. [Google Scholar]

- Inizan M.-L, Reduron-Ballinger M, Roche H, Tixier J. C.R.E.P; Nanterre, France: 1999. Technology and terminology of knapped stone. [Google Scholar]

- Iriki A. A prototype of Homo faber: a silent precursor of human intelligence in the tool-using monkey brain. In: Dehaene S, Duhamel J.-R, Hauser M.D, Rizzolatti G, editors. From monkey brain to human brain: a Fyssen foundation symposium. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. pp. 253–271. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Frey S.H. What's so special about human tool use? Neuron. 2003;39:201–204. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00424-0. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00424-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Frey S.H. The neural bases of complex tool use in humans. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2004;8:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.12.002. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2003.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Frey S.H, Newman-Norlund R, Grafton S.T. A distributed left hemisphere network active during planning of everyday tool use skills. Cereb. Cortex. 2005;15:681–695. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh169. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhh169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellenbach M.L, Brett M, Patterson K. Actions speak louder than functions: the importance of manipulability and action in tool representation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2003;15:30–45. doi: 10.1162/089892903321107800. doi:10.1162/089892903321107800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A.M, Garavan H. Human functional neuroimaging of brain changes associated with practice. Cereb. Cortex. 2005;15:1089–1102. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi005. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhi005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura D. Neuromotor mechanisms in the evolution of human communication. In: Steklis L.H.D, Raleigh M.J, editors. Neurobiology of social communication in primates. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1979. pp. 179–219. [Google Scholar]

- Klein R.G. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1999. The human career. [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E, Jubault T. Broca's Area and the hierarchical organization of human behavior. Neuron. 2006;50:963–974. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.017. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leakey M.D. Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960–1963. vol. 3. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1971. Olduvai Gorge. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J.W. Cortical networks related to human use of tools. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:211–231. doi: 10.1177/1073858406288327. doi:10.1177/1073858406288327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman P. On the nature and evolution of the neural bases of human language. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2002;45:36–62. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10171. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeilage P.F, Studdert-Kennedy M.G, Lindblom B. Functional precursors to language and its lateralization. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1984;246:R912–R914. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.6.R912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maravita A, Iriki A. Tools for the body (schema) Trends Cogn. Sci. 2004;8:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.12.008. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2003.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orban G.A, Claeys K, Nelissen K, Smans R, Sunaert S, Todd J.T, Wardak C, Durand J.-B, Vanduffel W. Mapping the parietal cortex of human and non-human primates. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2647–2667. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.11.001. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passingham R.E. The specializations of the human neocortex. In: Milner A.D, editor. Comparative neuropsychology. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1998. pp. 271–298. [Google Scholar]

- Passingham R.E, Sakai K. The prefrontal cortex and working memory: physiology and brain imaging. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2004;14:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.003. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passingham R.E, Toni I, Rushworth M.F.S. Specialisation within the prefrontal cortex: the ventral prefrontal cortex and associative learning. Exp. Brain Res. 2000;133:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s002210000405. doi:10.1007/s002210000405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M. The rostral-caudal axis of cognitive control within lateral frontal cortex. In: Dehaene S, Duhamel J.-R, Hauser M.D, Rizzolatti G, editors. From monkey brain to human brain: a Fyssen Foundation symposium. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof K.R, van den Wildenberg W.P.M, Segalowitz S.J, Carter C.S. Neurocognitive mechanisms of cognitive control: the role of prefrontal cortex in action selection, response inhibition, performance monitoring, and reward based learning. Brain Cogn. 2004;56:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.09.016. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2004.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijntjes M, Dettmers C, Buchel C, Kiebel S, Frackowiak R.S.J, Weiller C. A blueprint for movement: functional and anatomical representations in the human motor system. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:8043–8048. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-08043.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rilling J.K. Human and nonhuman primate brains: are they allometrically scaled versions of the same design. Evol. Anthropol. 2006;15:65–77. doi:10.1002/evan.20095 [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Arbib M.A. Language within our grasp. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1998;21:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Craighero L. The mirror–neuron system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;27:169–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144230. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Luppino G, Matelli M. The organization of the cortical motor system: new concepts. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1998;106:283–296. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(98)00022-4. doi:10.1016/S0013-4694(98)00022-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D. A systematic functional approach to language evolution. Camb. Archaeol. J. 2006;16:73–96. doi:10.1017/S0959774306000059 [Google Scholar]

- Roux V, David E. Planning abilities as a dynamic perceptual–motor skill: an actualistic study of different levels of expertise involved in stone knapping. In: Roux V, Bril B, editors. Stone knapping: the necessary conditions for a uniquely hominin behaviour. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research; Cambridge, UK: 2005. pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Schick K.D, Toth N. Simon & Schuster; New York, NY: 1993. Making silent stones speak: human evolution and the dawn of technology. [Google Scholar]

- Semaw S. The world's oldest stone artefacts from Gona, Ethiopia: their implications for understanding stone technology and patterns of human evolution 2.6–1.5 million years ago. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2000;27:1197–1214. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0592 [Google Scholar]

- Semaw S, Renne P, Harris J.W.K, Feibel C.S, Bernor R.L, Fesseha N, Mowbray K. 2.5-million-year-old stone tools from Gona, Ethiopia. Nature. 1997;385:333–336. doi: 10.1038/385333a0. doi:10.1038/385333a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele J, Uomini N. Humans, tools and handedness. In: Roux V, Bril B, editors. Stone knapping: the necessary conditions for a uniquely hominin behaviour. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research; Cambridge, UK: 2005. pp. 217–239. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan K.E, Marshall J.C, Friston K.J, Rowe J.B, Ritzl A, Zilles K, Fink G.R. Lateralized cognitive processes and lateralized task control in the human brain. Science. 2003;301:384–386. doi: 10.1126/science.1086025. doi:10.1126/science.1086025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout D. Skill and cognition in stone tool production: an ethnographic case study from Irian Jaya. Curr. Anthropol. 2002;45:693–722. doi:10.1086/342638 [Google Scholar]

- Stout D. Oldowan toolmaking and hominin brain evolution: theory and research using positron emission tomography (PET) In: Toth N, Schick K, editors. The Oldowan: case studies into the earliest Stone Age. Stone Age Institute Press; Gosport, IN: 2006. pp. 267–305. [Google Scholar]

- Stout D, Chaminade T. The evolutionary neuroscience of tool making. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.09.014. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout D, Toth N, Schick K. Acheulean toolmaking and hominin brain evolution: a pilot study using positron emission tomography. In: Toth N, Schick K, editors. The Oldowan: case studies into the earliest Stone Age. Stone Age Institute Press; Gosport, IN: 2006. pp. 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Studdert-Kennedy M, Goldstein L. Launching language: the gestural origins of discrete infinity. In: Christiansen M.H, Kirby S, editors. Language evolution. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2003. pp. 235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Toth N. Experiments in quarrying large flake blanks at Kalambo Falls. In: Clark J.D, editor. Kalambo Falls prehistoric site. The earlier cultures: Middle and Earlier Stone Age. vol. III. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. pp. 600–604. [Google Scholar]

- Wing A.M. Motor control: mechanisms of motor equivalence in handwriting. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:R245–R248. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00375-4. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00375-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn T. Archaeology and cognitive evolution. Behav. Brain. Sci. 2002;25:389–438. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000079. doi:10.1017/S0140525X02530120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Location of activated clusters found in contrasts between Oldowan toolmaking and control