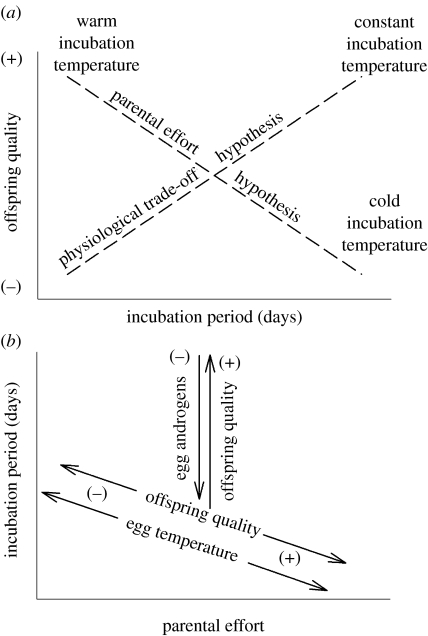

Figure 5.

Conceptual model for the possible interacting roles of embryonic temperature versus physiological trade-offs on offspring quality. Note that these reflect effects of temperature and physiological trade-offs within species that might differ among species. (a) Longer incubation periods (slower embryonic development) can produce higher quality offspring under the physiological trade-off hypothesis, where embryonic temperature is held constant and slower development reflects physiological trade-offs to enhance offspring quality. Longer incubation periods can have the opposite result and yield lower quality offspring under the parental effort hypothesis where decreased parental effort during incubation causes reduced incubation temperature that causes longer incubation periods. (b) Embryonic temperatures and physiological trade-offs can interact to influence offspring quality. Increasing parental effort (often this is a maternal effect, but in species that share incubation, it is a parental effect) can yield increasing egg temperature that leads to shorter incubation periods, shown by the arrows associated with ‘egg temperature’. Changes in incubation period related to egg temperature may yield correlated changes in offspring quality, as shown by the arrow with ‘offspring quality’ adjacent to egg temperature. For a constant parental effort (and egg temperature), increases in incubation period can reflect physiological trade-offs that enhance offspring quality (the up arrow), and may offset detrimental temperature effects. Maternal effects, through increased or decreased egg androgen concentrations, may provide one key proximate mechanism whereby mothers can shorten or lengthen incubation period and affect physiological trade-offs that determine offspring quality for a given parental effort (down arrow).