Abstract

An abstract of this study was presented at the American Association for Dental Research (AADR) Dental Anesthesiology Research Group in Honolulu, Hawaii, in March of 2004. This study was conducted to correlate the intraoperative and postoperative morbidity associated with moderate and deep sedation, also known as monitored anesthesia care (MAC), provided in a General Practice Residency (GPR) clinic under the supervision of a dentist anesthesiologist. After internal review board approval was obtained, 100 parenteral moderate and deep sedation cases performed by the same dentist anesthesiologist in collaboration with second year GPR residents were randomly selected and reviewed by 2 independent evaluators. Eleven morbidity criteria were assessed and were correlated with patient age, gender, American Society of Anesthesiology Physical Status Classification (ASAPS), duration of procedure, and anesthetic protocol. A total of 39 males and 61 females were evaluated. Patients' ASAPS were classified as I, II, and III, with the average ASAPS of 1.61 and the standard deviation (STDEV) of 0.584. No ASPS IV or V was noted. Average patient age was 33.8 years (STDEV, 14.57), and the average duration of procedure was 97.5 minutes (STDEV, 42.39). Three incidents of postoperative nausea and vomiting were reported. All 3 incidents involved the ketamine-midazolam-propofol anesthetic combination. All patients were treated and were well controlled with ondansetron. One incident of tongue biting in an autistic child was regarded as an effect of local anesthesia. One patient demonstrated intermittent premature atrial contractions (PACs) intraoperatively but was stable. Moderate and deep sedation, also known as MAC, is safe and beneficial in an outpatient GPR setting with proper personnel and monitoring. This study did not demonstrate a correlation between length of procedure and morbidity. Ketamine was associated with all reported nausea and vomiting incidents because propofol and midazolam are rarely associated with such events.

Keywords: Dental sedation, Sedation training, Sedation outcomes

Outpatient and office-based anesthesia is an integral part of the practice of dentistry. The dental profession has constantly reviewed its safety and efficacy track record in the provision of anesthesia care in the dental office. The use of pharmacologic methods of anxiety and pain control in general dental practice has been increasing. Studies demonstrate that dental fear and phobia exist in 15% to 30% of the general population in the United States.1 Mentally challenged patients often benefit from sedation, which improves access to care for this underserved group.2 General Practice Residency (GPR) training is an excellent venue by which general practitioners can receive education and training in many areas, including sedation. It is important to assess the safety and efficacy of sedation care in this environment as part of the continued effort of those in dentistry to evaluate its safety record.

The purpose of this study was to retrospectively and randomly evaluate the morbidity outcomes of 100 sedations conducted in a GPR clinic by second year GPR residents supervised by a dentist anesthesiologist with a general anesthesia/deep sedation permit. Several residents were involved in the provision of sedation care, and only 1 dentist anesthesiologist performed all evaluation procedures.

Methods

After approval was obtained from the University of Illinois at Chicago internal review board at the Office of Protection of Research Subjects, 100 sedation records were randomly selected from the general pool of sedation records by 2 independent evaluators, who reviewed these records for the morbidity criteria listed below. All evaluated procedures were conducted in the GPR clinic with the patient in the dental chair by a second year GPR resident under the supervision and direct involvement of a dentist anesthesiologist. All patients had nothing to eat or drink for 8 hours prior to administration of anesthesia. Through an indwelling angiocatheter IV access, patients were given lactated Ringer's solution as IV fluid continuous infusion. Patients who received propofol received it via infusion pump based on lean body weight. Nitrous oxide oxygen was given to patients via nasal hood, and capnography was monitored with a 14-gauge soft angiocatheter placed in the nares and attached directly to the sample line. A 4 × 4 gauze barrier was used intraorally during the procedure. Evaluators were 2 second-year GPR residents who were familiar with the sedation procedures and protocols used but were not involved in performing the evaluated procedures. Any events noted below were documented in the progress notes of the anesthesia records:

Respiratory distress, including loss of airway and/or desaturation below 90%

Bronchospasm

Laryngospasm

Cardiac arrhythmias and severe hypotension below 30% of baseline

Cardiac arrest

Allergic reactions or anaphylaxis

Tissue injury

Thrombophlebitis (manifested as inflammation and pain)

Seizures or neurologic injury

Nausea or vomiting, including aspiration

Unplanned hospitalization due to the above or any other causes

The following demographic details were tabulated and were correlated with morbidity outcomes:

Gender

Age

American Society of Anesthesiology Physical Status (ASAPS) classification

Duration of procedure

Sedation technique used

Results

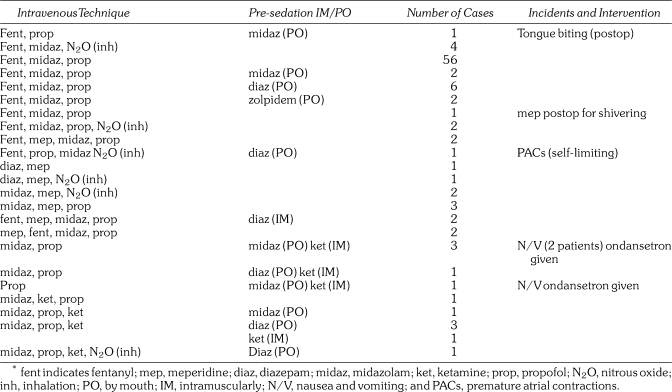

Records for 39 males and 61 females were evaluated. The average ASAPS was 1.61 with a standard deviation (STDV) of 0.584. Average patient age was 33.8 years with an STDV of 1.57 years. The average duration of procedure was 97.5 minutes with an STDV of 42.39 minutes. Table 1 outlines the various sedation techniques used in all 100 procedures.

Table 1.

Technique/Incidents and Interventions*

All procedures were conducted with the following monitors: 5-lead electrocardiogram, noninvasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, capnography, precordial stethoscope, and skin temperature. All events were recorded, and details were obtained from the anesthesia record progress notes. Three incidents of nausea and vomiting occurred in two 15-year-old males and one 17-year-old male. The first 15-year-old male had a history of mental delay, microcephaly, and dystonia. He underwent a dental examination, a cleaning, and a few restorations. The second patient was a 15-year-old autistic male who received an examination, x-rays, and scaling and root planing. The third patient was a 17-year-old male with a history of autism and gastroesophageal reflux disease. His medication list included esomeprazole (Nexium) and clonidine, and he received an examination, a cleaning, and sealants. All 3 patients were given IM ketamine (see Table 1) and ondansetron 0.15 mg/kg (IV); they were observed and eventually were discharged without the need for further intervention. One case of intraoperative premature atrial contractions (PACs), which was noted intraoperatively via 5-lead electrocardiogram, was transient and self-limiting, produced no other symptoms, and required no intervention. The patient, a 30-year-old female with a significant past medical history of hypothyroidism, attention-deficit disorder, and psychiatric disorder, exhibited no postoperative symptoms or recurrence. Her medication list included levothyroxine, nefazodone, fluoxetine, and carbamazepine. Her cardiac rhythm was reported to the patient and to her family, but given the patient's age and lack of any other symptoms, no emergency measures were taken, and she was advised to follow-up with her primary care physician, especially if palpitations, dizziness, or shortness of breath occurred. One case of tongue biting led to intraoral bleeding in a 14-year-old autistic female who had received an inferior alveolar nerve block for endodontic therapy while under IV deep sedation. The patient bit her tongue during the final phase of recovery because her tongue was numb. No suturing was needed, and follow-up was provided in the clinic to ensure adequate healing. ASAPS for all patients with reported morbidities was classified as ASAPS II. The bias of the study sample toward female versus male patients was coincidental and likely resulted from the random selection of records.

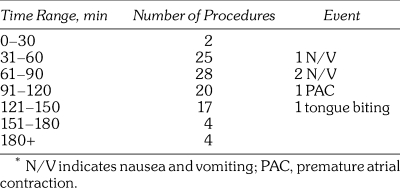

No incidents of allergic reaction, seizure, cardiac arrest, laryngospasm, thrombophlebitis, or unplanned hospitalization were noted. Table 2 lists the number of procedures as they pertain to procedure time range.

Table 2.

Time Range of Procedure Versus Morbidity Events*

Discussion

In 2006, Boynes et al3 published a study in the Journal of Dental Education. In this study, they surveyed general dentists who had graduated in 2003 regarding their education and competency in sedation and anesthesia. Most responders reported that they had little or no experience in this area. On the other hand, Dionne et al2 reported that nearly 30% of the general population in the United States express some level of dental fear. Chanpong et al4 recently published a Canadian National survey in Anesthesia Progress that revealed that almost 10% of the surveyed population experienced levels of dental fear that required administration of anesthesia with dental care. In 1998, Gordon et al2 published a study citing dental fear and anxiety as a barrier to access to care within the Special Needs population.

The Illinois survey published in 2007 by Flick et al5 showed that 5% of dentists who provide sedation and anesthesia care in the State of Illinois are general practitioners, and that the number of practicing periodontists rose from 0% to 9% over 10 years. Most dental practitioners who provided anesthesia care were oral surgeons who did so within the scope of their practice, and only 1% were dentist anesthesiologists.

Recently, 2 positive steps were taken to strengthen the provision of anesthesia care within the dental profession. First was the decision of the Commission on Dental Accreditation to include Dental Anesthesiology residency programs in its accreditation process; the second positive step occurred when the 2007 American Dental Association House of Delegates adopted new “Guidelines for the Use of Sedation and General Anesthesia by Dentists” and “Guidelines for Teaching of Pain Control and Sedation to Dentists and Dental Students.” Both of these documents aim to improve the level of competency and the standard of care in this very important area for the benefit of the American public. Although Yagiela6 predicted a bright future for office-based anesthesia in dentistry, in the absence of formal recognition of dental anesthesiology as a specialty in the United States, and given the limited number of residency programs in which dentists can receive such training, access to such care remains limited, and the bulk of sedation care in the general practice model still is provided by the operating general practitioner, although the variety and complexity of sedation techniques are often limited. Because significant sedation training is lacking in dental schools, as was discussed in the Boynes study, most sedation training may have to be provided during the postdoctoral phase of a dentist's education. For dentists already in general practice, continuing education courses in minimal or moderate enteral sedation have served as common sources of training in this area.

General Practice Residency programs (GPRs) and Advanced Education in General Dentistry have offered well-structured and extensive opportunities for dental residents to receive education and training up to the level of competency and/or proficiency in the areas of minimal enteral and moderate parenteral sedation. These programs provide a diverse patient population pool along with exposure to mentally, physically, and medically compromised patients, as well as fearful and phobic individuals. Credentialed general practitioners, dentist anesthesiologists, and dental specialists, particularly part-time oral surgeons, often conduct training in such programs. In our particular model, a dentist anesthesiologist was directly involved in the provision of care and in the training of participating second year residents.

Table 1 shows that in more than half of the study procedures, the same multidrug technique was used. However, this same table lists a variety of techniques, and one may speculate that most procedures were conducted under deep rather than moderate sedation. The presence of a dentist anesthesiologist certainly enabled the residents involved in patient care to conduct sedations at a deeper level than they would have done in private practice and to gain an in-depth experience in monitoring patients' vital signs and respiratory patterns and observing patient outcomes with different anesthesia techniques. All participating residents had completed a 1-month hospital operating room rotation in anesthesiology before they became involved in sedation care within the outpatient GPR clinic.

A survey7 of closed claims in 9 states revealed a total of 43 morbidities in dental offices from the period between 1974 and 1989. Hypoxia was the most commonly reported morbidity in this study. One may speculate that the advent of pulse oximetry and capnography toward the end of that period should have reduced the incidents of serious hypoxic events. Although Perrott et al8 reported a 1.3% morbidity risk in the oral surgery practice, it is not always possible to draw parallels between that model and the general practice model because operative procedures, depth of sedation, and average length of procedures are often markedly different.

All morbidities noted in this study were minor and were either self-limiting or easy to control, reflecting a very high level of safety. All nausea and vomiting cases involved IM ketamine at 3 mg/kg. This is consistent with the emetogenic properties of this drug. None of the reported morbidities involved transfer to a hospital or any irreversible or long-term debilitation. Some evaluators may consider this a zero morbidity outcome.

Conclusion

Investigators in this study concluded the following: (1) Sedations conducted on Special Needs and phobic patients in a GPR clinic supervised by a dentist anesthesiologist are effective and safe; (2) a very low level of self-limiting and reversible morbidities was reported in this study; (3) nausea and vomiting continue to be a common morbidity when ketamine is given intramuscularly; (4) GPR programs are an excellent venue for the training of general practitioners in the area of moderate sedation and can provide a strong alternative for the training of general practitioners in this area; and (5) the involvement of a dentist anesthesiologist in the training of GPR residents enabled them to acquire a broad and diverse experience in multidrug sedation techniques for Special Needs and phobic patients within the context of general practice.

This study did not demonstrate any correlation between length of procedure, ASAPS, patient age, and intraoperative morbidity. Larger studies are needed to ascertain the ultimate safety and efficacy of this educational model from both educational and clinical standpoints.

References

- Dionne R.A, Gordon S.M, McCullagh L.M, Phero J.C. Assessing the need for general anesthesia and sedation in the general population. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:167–173. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S.M, Dionne R.A, Snyder J. Dental fear and anxiety as a barrier to accessing oral health care among patients with special health care needs. Spec Care Dentist. 1998;18:88–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1998.tb00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynes S.G, Lemak A.L, Close J.M. General dentists' evaluation of anesthesia sedation education in US dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:1289–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanpong B, Haas D.A, Locker D. Need and demand for sedation or general anesthesia in dentistry: a national survey of the Canadian population. Anesth Prog. 2005;52:3–11. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006(2005)52[3:NADFSO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick W.G, Katsnelson A, Aldstrom H. Illinois Dental Anesthesia and Sedation Survey for 2006. Anesth Prog. 2007;54:52–58. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006(2007)54[52:IDAASS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagiela J.A. Office-based anesthesia in dentistry: past present and future trends. Dent Clin North Am. 1999;43:201–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippaehne J.A, Montgomery M.T. Morbidity and mortality from pharmacosedation and general anesthesia in the dental office. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:691–698. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90099-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrott D.H, Yuen J.P, Andresen R.V, Dodson T.B. Office-based ambulatory anesthesia: outcomes of clinical practice of oral and maxillofacial surgeons. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:893–895. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00668-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]