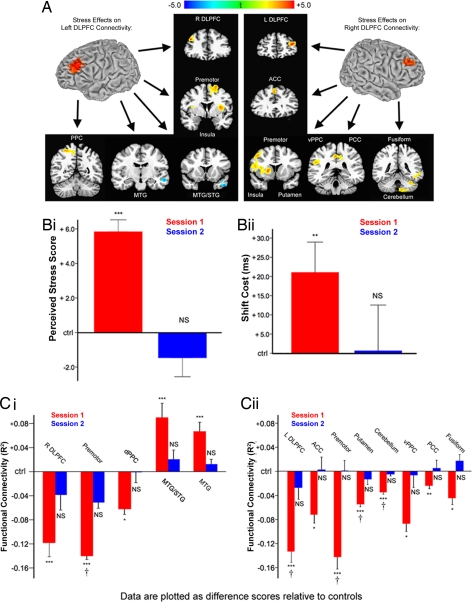

Fig. 3.

Chronic stress reversibly disrupted DLPFC functional connectivity. (A) Psychosocial stress exposure in the month preceding the first scanning session was associated with altered functional connectivity in left and right DLPFC. (Left) Stress decreased coupling between left DLPFC and right DLPFC, premotor, ventral PFC (insula), and posterior parietal cortex (PPC) relative to controls. Stress increased coupling with middle temporal lobe areas. (Right) Psychosocial stress decreased coupling between right DLPFC and left DLPFC, anterior cingulate (ACC), premotor, ventral PFC (insula), putamen, ventral PPC, posterior cingulate (PCC), fusiform cortex, and cerebellum. Maps represent post hoc t-tests of the stress effect. (B) Stress-exposed subjects were retested after 1 month of reduced stress and showed no differences from control subjects on PSS scores (i: t = 0.88, P = 0.39) or attention-shift costs (ii: t = 0.05, P = 0.96). (C) Stress effects on left (i) and right (ii) DLPFC functional connectivity reversed after 1 month of reduced stress for all areas tested except ventrolateral PFC. This reversal was confirmed by a significant stress-by-session interaction for all areas within a search volume that included voxels showing a significant main effect of stress overall. Other areas showed a comparable trend: stressed subjects showed altered connectivity in session 1 (red bars) but not in session 2 (blue bars). Data are plotted relative to mean values in low-stress control subjects. Error bars, SEM; NS, not significant; †, interaction significant at P < 0.05; t-tests, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005.