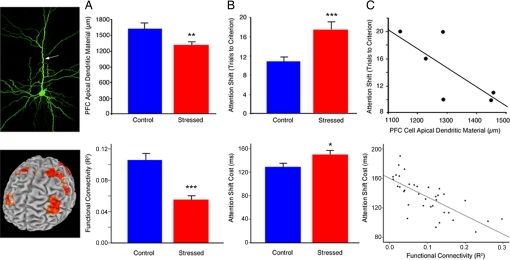

Fig. 4.

Stress effects on human PFC function (Bottom) are consistent with those observed in a rodent model of chronic stress (Top). Data from the rodent model are reproduced with permission from ref. 15 (Copyright 2006, The Journal of Neuroscience). (A) Chronic stress disrupted DLPFC functional connectivity in human subjects (t = 5.74, P < 0.001) and reduces apical dendritic arborization in rats (t = 2.83, P = 0.007). Human functional connectivity values represent the group means for peak voxels in each of the affected regions depicted in Fig. 3 A and C. (B) Stress-induced corresponding impairments in attention shifting [humans (Bottom), t = 2.10, P = 0.04; rats (Top), t = 3.51, P = 0.002). (C) Measures of PFC integrity predicted attention-shifting impairments in humans (Bottom) (r = −0.64, P < 0.001) and showed a similar trend in rats (Top) (r = −0.74, P = 0.09). Human functional connectivity values represent the means for peak voxels in each of the 6 regions depicted in the scatterplots in Fig. 2C. Error bars, SEM; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005.