The hospital, which is the “gold standard” for the delivery of acute medical care, is not an ideal care environment for many patients.1 Iatrogenic events such as nosocomial infections, pressure sores, falls and delirium are common.2 New functional impairment commonly occurs during hospital stay. Suboptimal transitions in care at the time of hospital discharge also occur, contributing, ironically, to readmission to hospital.3 Furthermore, hospital care is very expensive. In this issue, Shepperd and colleagues4 present a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of “hospital-at-home programs.”

Recent trends in health care favour alternatives to traditional acute care in hospitals. These include overcrowding of hospitals and emergency departments; rapid advancements in telehealth technologies that enhance the ability of clinicians to observe patients, conduct examinations and exchange information at distance; increased consumer expectations for better care experiences; and pressure from payers to develop high-quality, less-expensive alternatives to hospital care. Hospital-at-home care, which is generally defined as clinical services provided in association with acute inpatient care in the community, is such an alternative.

Many disparate models have been labelled as hospital at home in the international literature. These include outpatient infusion centres, physician office-based intravenous infusion services, early discharge programs, and substitutive or admission avoidance models. This variety has engendered controversy about the definition of hospital-at-home care, as well as its perceived overall effectiveness.5 A previous Cochrane review of all types of hospital-at-home care rendered a neutral verdict on the model's effectiveness6 and led to suggestions from others that hospital-at-home care needs to be defined more clearly as a substitutive (i.e., admission avoidance) model.7

In this context, it is useful to consider the systematic review and meta-analysis presented by Shepperd and colleagues4 in this issue. Their analysis was restricted to admission-avoidance hospital-at-home models and included 10 randomized controlled trials, 5 of which reported patient-level data. All of the included studies were from countries with single-payer systems: Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Italy. The main findings were a reduction in mortality that reached statistical significance at 6 months of follow-up. They also report a nonstatistically significant increase in hospital readmissions at 3 months. Other findings include a greater satisfaction with care, lower rates of complications and lower costs.

Restricting the analysis to substitutive models is an important advance. Despite this, there was substantial variation between the individual hospital-at-home programs with regard to the illnesses treated, acuity of patients, source of admission, origin and composition of the treatment teams, whether the patient was considered to be an inpatient while being treated in hospital at home, and the amount of physician and nursing care and coverage provided. There are reasons to believe that specific clinical components and processes affect outcomes. A recently published Italian hospital-at-home program that included frequent physician visits to the home and comprehensive geriatric assessment of patients demonstrated a substantial reduction in hospital readmissions.8

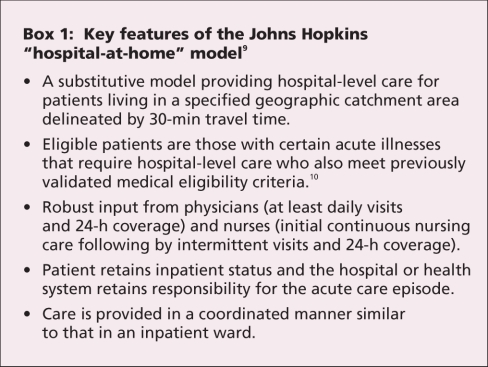

In the United States, development of hospital-at-home care has been slower and has essentially been limited to a model developed at Johns Hopkins.9 This model was tested in a prospective nonrandomized trial (randomization was precluded by federal regulations related to Medicare-managed care) in several Medicare-managed care organizations and a Veterans Affairs hospital. This trial demonstrated that substitutive hospital-at-home care was feasible and efficacious. Patients received timely hospital-level care at home that met quality standards. Compared with traditional acute hospital care, those who received treatment at home had fewer important clinical complications such as delirium, patient and family member satisfaction was higher, and costs of hospital-at-home care were lower. The key features of this program are listed in Box 1.

Box 1.

Despite the evidence supporting hospital-at-home care, it has had relatively limited dissemination, not only in the United States but also in countries where economic incentives for this type of care are better aligned. Hospital-at-home care is a complex clinical model11 and, as such, faces substantial dissemination barriers. To date, the evidence base is focused nearly exclusively on patient-related outcomes, rather than on outcomes of interest to potential adopter organizations. Although costing studies have been performed, these have focused mostly on costs of care and, to some degree, on operating costs. In contrast, the costs of implementation and the adoption process required within an organization have not been well delineated. Adoption of hospital-at-home care by a health system is akin to building a hospital unit from the ground up. Its entire infrastructure must be created before the first patient can be cared for, which represents a significant barrier to adoption. Based on my experience providing technical assistance to organizations adopting hospital at home, the process takes about 1 year of dedicated work by several project teams and collaborations among stakeholders within and often between organizations. Thus, hospital-at-home care is not an easy model to “pull off the shelf.”

However, in the United States, the paramount barrier to widespread dissemination of hospital-at-home care is that the predominant fee-for-service mode of health payment provides no incentive to adopt it because no payment structure exists to reimburse for the full complement of hospital-at-home services. Under current Medicare rules, payments to hospitals can only be provided for services that occur within the “bricks and mortar” of the hospital. Thus, to develop a hospital-at-home program, a fee-for-service hospital would be in the peculiar situation of taking patients out of reimbursed hospital beds and putting them into nonreimbursed hospital-at-home beds. Adoption of hospital-at-home care in the United States has been limited to integrated delivery systems, such as the Medicare-managed care and Veterans Affairs health systems. Development of a payment mechanism for hospital-at-home care in the fee-for-service arena using a Medicare-demonstration-mechanism waiver is pending approval. If accomplished, this would provide the economic incentives to spur development of hospital-at-home programs in the United States and promote the development of a more rigorous model definition and quality of care standards.

Further development of hospital-at-home care will require additional research and concurrent efforts to support dissemination. On the research side, investigators should adopt common definitions of hospital-at-home care or collect and report data on clinical components more explicitly to facilitate comparisons across models. They should also test hypotheses on the effects of different clinical components on outcomes. In addition, researchers should adopt common measures to enhance the comparison of data across studies and facilitate future meta-analyses. In addition to the research outcomes recommended by Shepperd and colleagues,4 other clinical outcomes of interest to stakeholders should be examined, including quality-of-care transitions, effects of hospital-at-home care on caregivers and prevention of nosocomial infections. Examination of such outcomes will likely require multisite studies to generate sufficient power. Programs to provide technical assistance that address clinical, financial and other aspects must be developed and used to facilitate the adoption of hospital-at-home care by interested health systems. As hospital-at-home care is disseminated more broadly, the field will need to face issues of model fidelity, as some adopters may be tempted to modify or dilute key features of the model, potentially compromising outcome benefits.

We must incorporate hospital-at-home care into the continuum of care without it becoming yet another siloed health care delivery model. Hospital-at-home care might operate best as 1 element in a portfolio of models for keeping certain patients out of acute care hospitals, treating those who must be admitted effectively and safely (avoiding iatrogenic illness), and helping patients transition out of hospital effectively. Such a portfolio of models will help hospitals and health systems provide high-quality care while simultaneously optimizing their economic interests. Planning efforts to develop the financial and technical assistance underpinnings of such an effort are underway.12

@@ See related research paper by Shepperd and colleagues, page 175

Key points.

Hospital-at-home care is generally defined as the community- based provision of services usually associated with acute inpatient care.

Many disparate models have been developed under the hospital-at-home label, leading to difficulties in evaluating their effectiveness.

Admission avoidance or substitutive hospital-at-home models are associated with reductions in mortality at 6 months and other benefits.

Hospital-at-home care faces substantial dissemination barriers.

Program development and implementation requires dedicated resources and may take as long as 1 year to establish.

Hospital-at-home care may be most successful as 1 element in a portfolio of models for keeping certain patients out of the acute care hospital, treating those who must be admitted effectively and safely, and helping patients transition out of hospital effectively.

Acknowledgments

I thank Ms. Deborah Statom for her assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Bruce Leff, Associate Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 5505 Hopkins Bayview Circle, Baltimore MD 21224, USA; fax 410 550-8701; bleff@jhmi.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed]

- 2.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:219-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:533-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Shepperd S, Doll H, Angus RM, et al. Avoiding hospital admission through provision of hospital care at home: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. CMAJ 2009;180:175-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Cheng J, Montalto M, Leff B. Hospital at home. Clin Geriatr Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Shepperd S, Iliffe S. Hospital at home versus in-patient hospital care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD000356. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Leff B, Montalto M. Home hospital-toward a tighter definition. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:2141. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Aimonino Ricauda N, Tibaldi V, Leff B, et al. Substitutive "hospital at home" versus inpatient care for elderly patients with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:493-500. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at home: feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:798-808. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Leff B, Burton L, Bynum JW, et al. Prospective evaluation of clinical criteria to select older persons with acute medical illness for care in a hypothetical home hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:1066-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ 2000;321:694-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Siu A, Spragens L, Inouye SK, et al. The ironic business case for chronic care using an acute care platform. Health Aff. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]