Abstract

Estradiol modulates dendritic spine morphology and synaptic protein expression in the rodent hippocampus, as well as hippocampal-dependent learning and memory. In the rat, these effects may be mediated through nongenomic steroid signaling such as estradiol activation of Akt and LIMK pathways, in addition to genomic signaling involving estradiol upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression (BDNF). Due to the many species differences between mice and rats, including differences in the hippocampal response to estradiol, it is unclear whether estradiol modulates these pathways in the mouse hippocampus. Therefore, we investigated whether endogenous fluctuations of gonadal steroids modulate hippocampal activation of Akt, LIMK, and the BDNF receptor TrkB in conjunction with spatial memory in female mice. We found that Akt, LIMK, and TrkB were activated throughout the dorsal hippocampal formation during the high-estradiol phase of proestrus compared to diestrus. Cycle phase also modulated expression of the pre- and post-synaptic markers synaptophysin and PSD-95. However, cycle phase did not influence performance on an object placement test of spatial memory, although this task is known to be sensitive to the complete absence of ovarian hormones. The findings suggest that endogenous estradiol and progesterone produced by the ovaries modulate specific signaling pathways governing actin remodeling, cell excitability, and synapse formation.

Keywords: estrogen, steroid, spine, plasticity, memory

The hippocampal formation is a medial temporal lobe structure of the mammalian brain implicated in the formation of episodic and spatial memories and the control of emotion (Kandel et al., 2000). Among the many endogenous regulators of hippocampal function, the ovarian steroids estrogen and progesterone stand out for their relevance to human health and disease. In humans, mood, cognition, and hippocampal activation fluctuate in concert with circulating ovarian steroid levels across the menstrual cycle (Rosenberg and Park, 2002, Halbreich et al., 2003, Protopopescu, 2006). Similarly, in laboratory rats and mice, estrous cycle phase modulates hippocampal excitability and some hippocampal-dependent behaviors (Terasawa and Timiras, 1968, Frick and Berger-Sweeney, 2001, Scharfman et al., 2003, Korol et al., 2004). In the rat, spine density on pyramidal cell dendrites in the CA1 stratum radiatum also fluctuates in concert with estradiol levels across the estrous cycle (Woolley et al., 1990).

Studies using the classic endocrine paradigm of ovariectomy and estradiol replacement confirmed that estradiol increases CA1 dendritic spine and synapse density (Gould et al., 1990, Woolley and McEwen, 1992, MacLusky et al., 2005). We now know that estradiol induces maturation of dendritic spines in both rat and mouse CA1, and increases the expression of several synaptic marker proteins in the hippocampus of mouse, rat, and rhesus monkey (Woolley and McEwen, 1992, Brake et al., 2001, Hao et al., 2003, Rapp et al., 2003, Li et al., 2004, Gonzalez-Burgos et al., 2005, Hao et al., 2006, Jelks et al., 2007, Spencer et al., 2007). This estradiol modulation of spines and synapses may have functional consequences, as estradiol also enhances performance on hippocampal-dependent spatial memory tasks in rats and mice (Korol, 2004, Li et al., 2004, Sandstrom and Williams, 2004, Spencer et al., 2007). These findings indicate that circulating estradiol modulates dendritic spine morphology and synapse density on pyramidal cells of the mammalian hippocampus, and that this modulation results in estradiol-mediated enhancement of hippocampal function. Currently, our work focuses on identifying the upstream regulators of these effects.

Estradiol in the brain may act through a combination of classical nuclear hormone signaling, and more rapid, “nongenomic” signaling. Rapid activation of cell signaling cascades by estradiol has been described, suggesting that estradiol activates membrane receptors (Levin, 2005, Spencer et al., 2007). For example, in the NG108-15 neuroblastoma cell line, estradiol treatment results in phosphorylation of the Akt molecule (Akama and McEwen, 2003, Yuen, 2006). Rapid actions of estradiol may be important for its downstream effects on dendritic spine morphology and synapse formation. Indeed, in NG108-15 cells, estradiol activation of Akt results in filopodia formation and translation of the post-synaptic density 95 (PSD-95) protein (Akama and McEwen, 2003). In the brain, estradiol treatment increases phosphorylation of Akt in CA1 pyramidal cells and dendrites of ovariectomized female rats and in the striatum of male C57BL/6 mice (Znamensky et al., 2003, D'Astous et al., 2006). This suggests that Akt may be an important upstream effector of estradiol actions in the brain.

The rapid, nongenomic actions of estradiol may result from signaling through classical or nonclassical estrogen receptors localized on or near the membrane (Pedram et al., 2006). The localization of immunoreactivity (IR) for membrane-associated estrogen receptors alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ) in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus (Milner et al., 2001, Milner et al., 2005), the area most sensitive to estradiol-induced spine and synapse formation (Woolley and McEwen, 1992), suggests that some rapid actions of estradiol in the hippocampus may occur via signaling through a membrane-localized classical estrogen receptor (Milner et al., 2001, Milner et al., 2005). Finally, although most studies have investigated the effects of several days of estradiol treatment on spine density and behavior, two studies demonstrated that estrogenic compounds can enhance hippocampal-dependent behavior and increase CA1 spine density within hours (Luine et al., 2003, MacLusky et al., 2005), a temporal course consistent with the role of rapid actions of estradiol in downstream morphological and behavioral effects in vivo.

Our laboratory has recently provided evidence that nongenomic estradiol signaling in neurons may regulate the cellular machinery for actin remodeling, which governs the formation and turnover of estrogen-sensitive dendritic spines and synapses in hippocampal pyramidal cells (Yuen, 2006). In hippocampal cells, the actin depolymerizing factor, cofilin, and its regulatory kinase, LIM Kinase (LIMK), may be particularly important modulators of dendritic spine dynamics implicated in lasting cellular changes such as long-term potentiation (Meng et al., 2003). Studies of a LIMK knockout mouse have implicated LIMK in spine morphology and hippocampal function in vivo (Meng et al., 2002). Estradiol activates LIMK in the NG108-15 cell line via PI3 kinase-dependent activation of Rac1, leading to deactivation of cofilin and filopodia formation (Yuen, 2006). This suggests that estradiol may regulate dendritic spine density and maturation through the LIMK/cofilin pathway. Indeed, estradiol also increases pLIMK-IR in primary hippocampal cells and in the CA1 stratum radiatum of ovariectomized rats (Yildrim et al., 2005, Yuen, 2006).

Although estradiol’s ability to regulate dendritic spine dynamics, spine formation, and synaptic protein expression depend on signaling through estrogen receptors (McEwen et al., 1999, Yuen, 2006, Jelks et al., 2007, Spencer et al., 2007), it is likely that other membrane proteins, such as neurotrophin receptors, participate in these effects. Substantial evidence indicates that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may be important for estradiol effects in the hippocampal formation. Exogenous estradiol administration to ovariectomized rats increases BDNF mRNA and protein expression in the hippocampus (Gibbs, 1998, Jezierski and Sohrabji, 2001, Scharfman et al., 2003, Zhou et al., 2005). Activation of the BDNF receptor TrkB in the hippocampal formation leads to LIMK and Akt phosphorylation, dendritic spine regulation, and enhancement of long-term potentiation, similar to the effects of estradiol (Chao, 2003, Scharfman and Maclusky, 2005, Scharfman and Maclusky, 2006a, Spencer et al., 2007).

In sum, emerging evidence suggests that estradiol modulates several overlapping cellular pathways in the hippocampal formation leading to enhancement of hippocampal function. The current model suggests that in rats, estradiol activates the PI3K pathway, resulting in Akt activation, LIMK activation, and increased PSD-95 expression, leading to actin remodeling and maturation of dendritic spines. Additionally, estradiol induces BDNF expression, followed by BDNF release and TrkB activation, leading to increased pyramidal cell excitability, enhanced long-term potentiation, and Akt/LIMK activation. Despite this extensive progress in research using rats, very few studies have investigated the mechanism of estradiol modulation of synaptic protein expression, dendritic spine density, and hippocampal function in female mice. Previous work demonstrates differences in the estradiol sensitivity of the mouse and rat hippocampal formation that suggest possible differences in the mechanism of steroid actions in these two species. For example, while estradiol increases synaptic protein expression mainly in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus, it induces a widespread increase in synaptic protein expression throughout the mouse hippocampal formation (Brake et al., 2001, Li et al., 2004). Additionally, while estradiol increases the total dendritic spine density as well as the density of mature “mushroom” shaped spines in the rat CA1, only mushroom spines increase in the mouse CA1 (Gould et al., 1990, Li et al., 2004). Finally, in the dentate gyrus, neurogenesis increases after estradiol treatment in the rat, but not the mouse (Lagace et al., 2007, Galea, 2008). Because of these differences and the preponderance of genetic tools available in mice, it is necessary to determine whether endpoints known to be sensitive to circulating ovarian steroids in the female rat hippocampus are similarly sensitive in mice.

The choice of a cycling mouse model provides two advantages over the popular ovariectomy and estrogen replacement model for the initial verification of steroid-sensitive endpoints in the mouse hippocampus. First, it is difficult to establish a regimen of hormone replacement in ovariectomized mice that is “equivalent” to those regimens commonly used in rats. In rats, estradiol effects on CA1 dendritic spine density, hippocampal Akt activation and BDNF expression, and spatial memory have been demonstrated in both ovariectomized animals replaced with estradiol and in naturally cycling rats during the high-estradiol phase of proestrus (Woolley et al., 1990, Scharfman et al., 2003, Znamensky et al., 2003, Korol et al., 2004, Gonzalez-Burgos et al., 2005). Therefore, investigating cyclic changes in several of these endpoints is a reasonable starting point to establish which pathways are sensitive to physiological concentrations of circulating estrogens in mice. Second, studies in young cycling animals are more immediately relevant to women than studies of young adult ovariectomized animals. Investigations of hippocampal sensitivity to the estrous cycle may be relevant to neurologic and psychiatric disorders related to the human menstrual cycle, such as catamenial epilepsy and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (Halbreich et al., 2003, Scharfman and MacLusky, 2006b, Huo et al., 2007).

Based on studies of estradiol and estrous cycle sensitivity of the rat hippocampus, we chose several endpoints and examined their regulation by the estrous cycle in female mice. Activation of Akt, LIMK, and TrkB, and the expression of the pre-and post-synaptic proteins synaptophysin and PSD-95, was assessed using quantitative immunocytochemistry in several subregions of the dorsal hippocampal formation of cycling mice. The object placement test of spatial memory was used to correlate hippocampal function with the immunocytochemical findings.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Rockefeller University and were in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Female C57Bl6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA). Animals were housed on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum for the duration of the study. Animals were collected for immunocytochemical analysis or underwent behavioral testing at 8–10 weeks of age.

Vaginal Cytology

Mice were given one week after arrival to acclimate to the animal housing facility. Vaginal swabs were then taken daily and vaginal cytology was observed under a microscope after staining with the Hema 3 Stain Set from Fisher Scientific Company L.L.C. (Kalamazoo, MI). Cycle phase was determined as proestrus, estrus, early diestrus or late diestrus according to published criteria (Turner and Bagnara, 1971). Mice without progression through the distinct cytologic stages of proestrus, estrus and diestrus were excluded from the study. Vaginal cytology was monitored for at least one complete cycle before brain collection or behavioral testing.

Whole Brain Preparation

Mice (n=25) were anesthetized on the morning of proestrus, estrus, or diestrus with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg intraperitoneal) and perfused with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4; PB). Brains were removed from the skull and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour. They were then sunk in 30% sucrose in PB for 48 hours at 4°C, and frozen at −80°C until sectioning. Sections (40 µm thick) through the hippocampal formation were cut on a freezing microtome (Microm HM440E). Sections were stored in a cryoprotectant solution of 50% ethylene glycol, 15% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) until use in immunohistochemical procedures.

Antibodies

Primary antibodies used in this study are listed below. Serial dilution tests of each antibody established that the labeling intensity was linear, and antibody dilutions were chosen that produced slightly less than half-maximal labeling intensity to optimize the detection of intensity variations (Chang et al., 2000).

Monoclonal mouse anti-synaptophysin (1:450,000) purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) (Brake et al., 2001). Specificity of the antibody has been confirmed by Western blot. Monoclonal mouse anti-PSD-95 (1:20,000) purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Polyclonal rabbit anti-phosphothreonine 508 LIMK1/2 (1:500) purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Specificity of the antibody has been confirmed by Western blot (Yildrim et al., 2005, Yuen, 2006).

Polyclonal rabbit anti-phosphothreonine 308 Akt (1:1500) purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Specificity of the antibody has been confirmed by Western blot and preadsorption controls in acrolein/paraformaldehyde-fixed tissue (Znamensky et al., 2003).

Polyclonal rabbit anti-phosphotyrosine 515 TrkB (1:4000), a gift from Moses Chao at New York University. Specificity of the antibody has been confirmed by Western Blot (Arevalo et al., 2006). Preadsorption with pTrkB peptide completely eliminates immunocytochemical staining.

Immunocytochemistry and Densitometry

Immunocytochemistry and quantitative densitometry was performed on sections through the dorsal hippocampal formation level 29 of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1998) as previously described (Znamensky et al., 2003). To ensure identical labeling conditions, tissue from each experimental condition was marked with identifying punches and all conditions were pooled during labeling procedures. Moreover, tissue from at least 3 sets of mice was processed together (Pierce et al., 1999). Briefly, sections were washed in 0.1 M Tris saline (TS), blocked in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated in primary antiserum for 24 hours at room temperature followed by 48 hours at 4°C. Sections were then incubated in: (1) biotinylated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody in 0.1% BSA (1:400; Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes, avidin biotin complex (ABC) for 30 minutes (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), and diaminobenzidine with H2O2 (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) for 6 minutes, with TS washes in between each incubation. Sections then were mounted on SuperFrost Plus slides from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), air-dried, and converslipped with DPX mounting medium (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI). Images for densitometric analysis were captured on a Nikon E800 microscope using a Dage CCD C72 camera and control unit using preset gain and black levels, a Data Translation Quick capture card, and NIH Image 1.50 software. To compensate for uneven illumination, blank fields from a slide without tissue were subtracted. To prepare figures, the levels, brightness and contrast were adjusted in Adobe Photoshop 7.0 on a Macintosh Powerbook G4. Final figures were assembled in Microsoft Powerpoint (Version 11.3.5).

Quantitative Analysis

The average pixel density (of 256 gray levels) for each selected region was determined using NIH Image. To compensate for background staining and control of variations in illumination level between images, the average pixel density for 3 small regions that lack labeling was determined within each captured image, and subtracted from all density measurements made on that image. Subregions of dorsal hippocampal formation from which pixel density was measured for each mouse are shown in Figure 1. Sampled areas included the CA1 stratum radiatum, CA3 strata lucidum and radiatum, the hilus of the dentate gyrus, and in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (pTrkB-labeled sections only). To confirm that the observed phenomena were specific to hippocampal formation, measurements also were taken from layers 2/3 of somatosensory cortex overlying the dorsal hippocampal formation.

Figure 1.

Density of peroxidase labeling was quantified in subregions of the dorsal hippocampal formation at −1.28 mm from bregma, shown on this section of dorsal hippocampus labeled for synaptophysin. Hippocampal subregions were chosen based on the anatomy of neuronal projections, previously demonstrated hormone sensitivity, and ease of identification in labeled sections. Additional measurements were taken from the sensory cortex overlying the dorsal hippocampus (not shown). All measurements were normalized to background measurements taken from the corpus callosum in the same image. CA1 SR, CA1 stratum radiatum; CA3 SL, CA3 stratum lucidum; CA3 SR, CA3 stratum radiatum; DGHIL, hilus of the dentate gyrus; SGZ, subgranular zone (pTrkB only); CC, corpus callosum. For all subsequent quantitative immunohistochemistry, n = 4 for proestrus, 6 for estrus, and 11 for diestrus.

Object Placement Test of Spatial Memory

Mice (n=16) mice underwent behavioral testing on the object placement task as previously described (Li et al., 2004). Testing consisted of two trials, the sample trial (T1) and recognition trial (T2) separated by a delay. During the T1 trial, the mouse explored two identical objects (objects 1 and 2) at one end of an open field measuring 45 cm × 45 cm for 5 minutes. During the T2 trial, the mouse explored the same two objects, with object 1 in the original location and object 2 in a new location. Mice were acclimated to the apparatus, objects, and task for three days before testing. The first day of acclimation consisted of a 5-minute open field trial. Two successive days of acclimation consisted of object placement testing with delays of 5 minutes and then 15 minutes. Following acclimation, each mouse was tested on the object placement task three times with a 30-minute delay, in each of three estrous cycle phases, proestrus, estrus, and diestrus. The same two objects were used throughout testing. Object start locations and new object locations were counterbalanced across mice, trials, and cycle phases. Trials were recorded and analyzed using the Noldus Ethovision XT software (Noldus Information Technology, Leesburg, VA). An area of 1 cm surrounding the objects was delineated using the software, and object exploration was defined as when the nose of the mouse was within this object surround area. These mice were sacrificed at the completion of testing in proestrus, estrus, or diestrus, and blood levels of estradiol were assessed using the estradiol ELISA from Bio-Quant, Inc. in San Diego, CA.

Statistical Analyses

Relative optical densities (ROD) from densitometric analysis were compared between cycle phases using a two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with hippocampal subregion and cycle phase as the independent measure and ROD as the dependent measure. Post-hoc comparisons were made using the Fisher’s PLSD. For object placement testing, amount of time spent exploring object 2 was expressed as a fraction of total time spent exploring both objects in the T1 trial (T1 fraction) T2 trial (T2 fraction). For each trial T1 and T2, these fractions were compared using a one-sample t-test to determine whether they deviated significantly from chance (0.5). T2 fractions were further analyzed using a repeated-measures ANOVA with cycle phase and test number as the within-factor. Post-hoc comparisons were made using the Fisher’s PLSD. Total distance traveled and total time exploring objects in the T1 trial was also analyzed in this manner.

Results

Female C57BL6 mice have uniform 6-day estrous cycles

To be able to meaningfully study estrous cycle variations in markers related to non-genomic signaling and neuronal structural plasticity, estrous cycles for the 16 mice undergoing behavioral testing were monitored daily with vaginal smears for several weeks, enabling observation of cycle characteristics. The mice used for this study had uniform estrous cycles with an average length of 6.1 +/− 0.30 days. Fig. 2 shows that mice spent an average of 1.1 day in proestrus, 2.5 days in estrus, and 2.5 days in diestrus. Circulating estradiol levels were higher in proestrus (31.9 +/− 11.80 pg/ml) than in estrus (20.7 +/− 1.84 pg/ml) or diestrus (17.4 +/− 5.56 pg/ml). However, due to considerable variation in sample quality and estradiol levels, these changes in circulating estradiol levels were not significant.

Figure 2.

The C57BL6 female mice used in this study had regular, 6.1-day estrous cycles. As assessed by daily morning vaginal smears, 1.1 days (18%) of the cycle were spent in proestrus, 2.5 days (41%) in estrus, and 2.5 days (41%) in diestrus. Mice were perfused as indicated with arrows in proestrus, early estrus, and early diestrus. Error bars show standard error of the mean.

Akt is activated during proestrus and inactivated during estrus

To determine whether natural fluctuations in gonadal steroids in female mice modulate the activation of Akt, activation of Akt was measured as pAkt IR in the hippocampal formation (Fig. 3). Similar to rats (Znamensky et al., 2003), pAkt IR in mice localized to cell bodies and processes of hippocampal pyramidal cell bodies and dentate granule cells. The densest labeling was seen in pyramidal cell bodies and strata lucidum and lacunosum-moleculare of the hippocampus proper. pAkt IR was measured in CA1 stratum radiatum, CA3 strata radiatum and lucidum, and hilus of the dentate gyrus of the dorsal hippocampal formation. Two-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of brain region (F(3,117.2)=4.5, p<0.01), and a significant effect of cycle phase (F(2,418.5)=15.9), p<0.0001, but no interaction between the two factors (F(6,13.2)=0.5, p=0.81). This suggests that cycle phase influenced pAkt IR in all subregions in the same manner. Post-hoc tests revealed that pAkt IR was highest in the CA1 stratum radiatum and CA3 stratum lucidum regions. pAkt IR was significantly higher in proestrus than in estrus (p<0.0001) or diestrus (p<0.05). In addition, pAkt-IR was higher in diestrus than in estrus (p=0.0001). This indicates that Akt in the dorsal hippocampus is activated during the high-estradiol phase of the cycle, proestrus, and inactivated during the ensuing estrus phase, after circulating estradiol levels have fallen. An intermediate level of Akt activation occurs during diestrus, when estradiol levels are still low and progesterone levels rise (Walmer et al., 1992).

Figure 3.

Akt is activated during proestrus and inactivated during estrus. A, Images of peroxidase labeling of phosphorylated Akt in the dorsal hippocampal formation of representative sections from one proestrus and one estrus mouse. pAkt immunoreactivity (IR) is darker throughout the hippocampus in proestrus than in estrus. B, quantification of pAkt-IR in four hippocampal subregions across the estrus cycle. pAkt=IR was significantly higher in proestrus compared to estrus (p<0.0001), and in diestrus compared to estrus (p=0.0001). R.O.D., relative optical density.

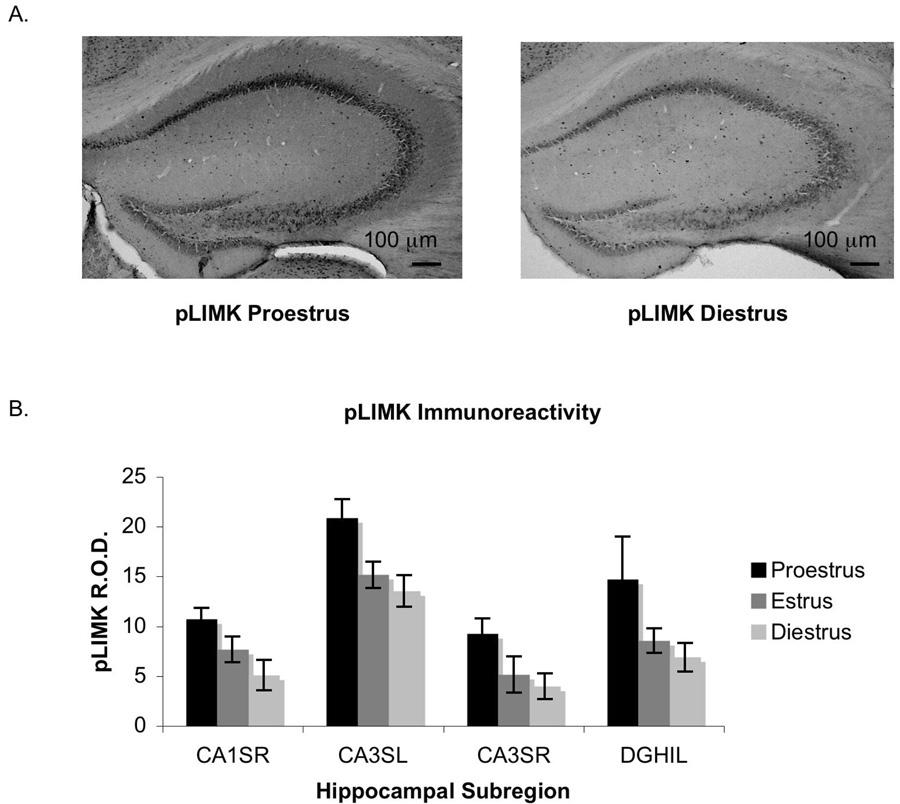

LIMK is activated during proestrus and inactivated during estrus and diestrus

To determine whether natural fluctuations in gonadal steroids modulate the activation state of LIMK in female mice, activated LIMK was measured as pLIMK IR in the hippocampal formation (Fig. 4). Phosphorylated LIMK localized to the cell bodies and processes of hippocampal pyramidal cells and granule cells of the dentate gyrus. pLIMK IR was measured in CA1 stratum radiatum, CA3 strata radiatum and lucidum, and hilus of the dentate gyrus of the dorsal hippocampal formation. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of brain region (F(3,361.3)=18.6, p<0.0001) and cycle phase (F(2,243.0)=12.5, p<.0001) but no interaction between the two factors (F(6,3.3)=0.17, p=0.98). Post-hoc tests revealed that pLIMK IR was highest in the CA3 stratum lucidum. pLIMK IR was significantly higher in proestrus than in estrus (p<0.01) and diestrus (p<0.0001). This indicates that estrous cycle phase modulates LIMK activation in the dorsal hippocampal formation. Activation is high during the high-estradiol phase of the cycle, proestrus, and low during the estrus and diestrus phases, when circulating estradiol levels are low.

Figure 4.

LIMK is activated during proestrus. A, Images of peroxidase labeling of phosphorylated LIMK in the dorsal hippocampal formation of representative sections from one proestrus and one diestrus mouse. pLIMK IR is darker throughout the hippocampus in proestrus than in diestrus. B, quantification of pLIMK-IR in four hippocampal subregions across the estrous cycle. pLIMK-IR was significantly higher in proestrus than in estrus (p<0.01) or diestrus (p<0.0001).

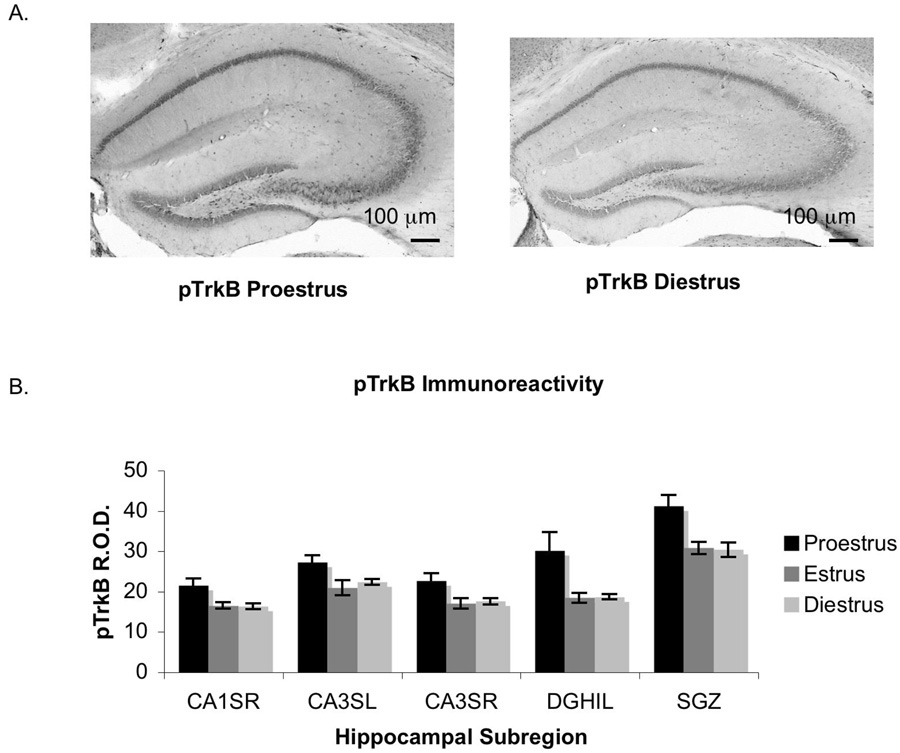

pTrkB is activated during proestrus and inactivated during estrus and diestrus

To determine whether natural fluctuations in gonadal steroids modulate the activation state of the BDNF receptor TrkB in female mice, activated TrkB was measured as pTrkB IR in the dorsal hippocampal formation (Fig. 5). Immunoreactivity for the TrkB receptor ligand BDNF is strongest in the mossy fiber pathway (Scharfman et al., 2003), and so it was not surprising to see pTrkB labeling in the CA3 projection area of this pathway. Phosphorylated TrkB also localized to cell bodies and processes of hippocampal pyramidal cells throughout the stratum radiatum, and in the granule cells of the dentate gyrus. In addition, pTrkB labeled cells in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the dentate gyrus, an area that gives rise to newly born neurons that integrate into hippocampal circuits (Doetsch and Hen, 2005). Finally, pTrkB labeled glial cells throughout the hippocampal formation.

Figure 5.

The neurotrophin receptor TrkB is activated during proestrus. A, Images of peroxidase labeling of phosphorylated TrkB in the dorsal hippocampal formation of representative sections from one proestrus and one diestrus mouse. pTrkB IR is darker throughout the hippocampus in proestrus than in diestrus. B, quantification of pTrkB-IR in five hippocampal subregions. pTrkB-IR was significantly higher in proestrus compared to estrus and diestrus (p<0.0001).

pTrkB IR was measured in the CA1 stratum radiatum, CA3 strata radiatum and lucidum, and hilus and SGZ of the dentate. Two-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of brain region (F(4,633.5)=45.0, p<0.0001) and cycle phase (F(2,460.4)=32.7, p<0.0001), but no interaction (F(8,17.2)=1.2, p=0.30). Post-hoc tests revealed that pTrkB IR was highest in the SGZ, and higher in the stratum lucidum and dentate hilus than in the stratum radiatum. pTrkB IR was significantly higher in proestrus than in estrus and diestrus (p<0.0001). This indicates that TrkB activation in the dorsal hippocampus is high during the high-estradiol phase of the cycle, proestrus, and low during the low-estradiol phases of estrus and diestrus.

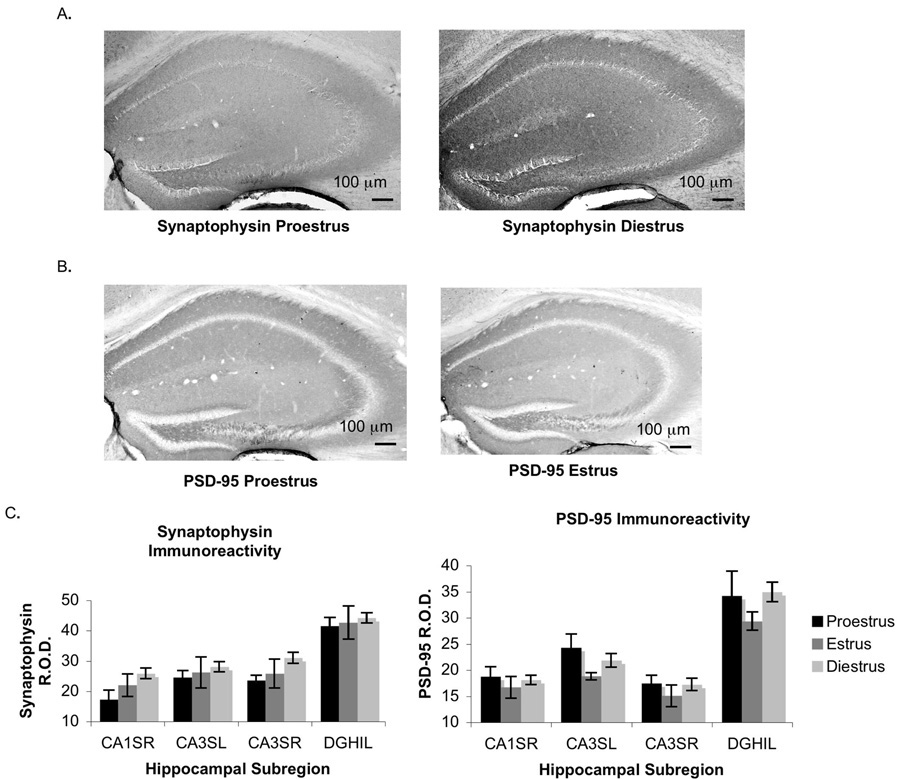

Synaptic protein expression fluctuates across the estrous cycle

To determine whether natural fluctuations of gonadal hormones also modulate expression of synaptic proteins, immunoreactivity for PSD-95 and synaptophysin was examined in the dorsal hippocampal formation of cycling mice (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Expression of the presynaptic protein synaptophysin and the postsynaptic protein PSD-95 fluctuates across the mouse estrous cycle. A and B, representative images from the dorsal hippocampal formation of synaptophysin and PSD-95 IR in mice at different stages of the estrous cycle. C, quantification of synaptophysin and PSD-95 IR in four hippocampal subregions. Synaptophysin IR was significantly higher in diestrus than in proestrus (p<0.05). In contrast, PSD-95 IR was higher in proestrus than in estrus (p<0.05) or diestrus (p<0.01).

The post-synaptic scaffold protein PSD-95 was absent from cell bodies of hippocampal pyramidal cells and dentate granule cells, but was seen in all other areas containing cell processes in the hippocampal formation. PSD-95 IR was measured in the CA1 stratum radiatum, CA3 strata radiatum and lucidum, and dentate hilus. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of brain region (F(3,950.6)=44.6, p<0.0001) and cycle phase (F(2,90.1)=4.2, p<0.05), but no interaction. PSD-95 IR was highest in the dentate hilus. Post-hoc tests revealed that PSD-95 was higher during proestrus than estrus (p<0.05) or diestrus (p<0.01).

The distribution of the pre-synaptic protein synaptophysin was similar to that of PSD-95, and immunoreactivity was measured from the same areas. As with PSD-95, two-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of brain region (F(3, 1507)=24.5, p<0.0001) and cycle phase (F(2,202.3)=3.3, p<0.05), but no interaction. Synaptophysin IR was also highest in the hilus. In contrast to PSD-95, synaptophysin IR was higher during diestrus than proestrus (p<0.05).

In summary, the pre-synaptic protein synaptophysin and post-synaptic protein PSD-95 have distinct patterns of expression in the hippocampal formation across the mouse estrous cycle. PSD-95 IR increases, and synaptophysin-IR decreases, during proestrus when circulating estradiol levels are highest. Synaptophysin IR increases during diestrus, when circulating estradiol levels are low and progesterone levels are high.

Cyclic fluctuation of signaling and synaptic protein expression is specific to the hippocampal formation

To determine whether the above findings of cyclic fluctuation of cell signaling and synaptic protein expression were specific to the hippocampal formation rather than global cerebral responses to vascular or metabolic changes across the cycle, immunoreactivity from of all five endpoints reported above was measured in the sensory cortex overlying the dorsal hippocampus in the same image from which hippocampal measurements were taken (Table 1). Labeling for all endpoints was detectable above background (corpus callosum) levels. Data for each endpoint were analyzed as a one-way ANOVA with cycle phase as the independent variable. No significant differences were detected between cycle stages in the cortex for any of the endpoints measured.

Table 1. Somatosensory Cortex (R.O.D.).

Cyclic fluctuation of signaling and synaptic protein expression is specific to the hippocampal formation. Immunoreactivity for pAkt, pLIMK, pTrkB, PSD-95, and synaptophysin was quantified from the somatosensory cortex overlying the dorsal hippocampal formation. Values were normalized to corpus callosum. No significant differences were found across the estrous cycle for any of the five endpoints. R.O.D., relative optical density.

| Proestrus | Estrus | Diestrus | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pAkt | 24.5 +/− 2.2 | 27.0 +/− 1.3 | 24.0 +/− 1.1 |

| pLIMK | 15.5 +/− 4.0 | 16.2 +/− 2.8 | 11.6 +/− 1.7 |

| pTrkB | 22.6 +/− 3.4 | 23.6 +/− 2.1 | 20.0 +/− 1.9 |

| PSD-95 | 15.4 +/− 3.2 | 12.1 +/− 1.6 | 14.3 +/− 1.6 |

| synaptophysin | 8.2 +/− 4.2 | 9.9 +/− 1.9 | 6.4 +/− 1.7 |

Estrous cycle does not affect performance on the object placement test

The object placement task tests recognition of the novel placement of one of two identical objects after it is moved to a new location between the sample (T1) and recognition (T2) trials (Fig. 7A). In this study, the two trials were 30 minutes apart. The nature of this task allows animals to be tested more than once. Accordingly, each mouse was tested in all three phases of the estrous cycle: proestrus, estrus, and diestrus. Four of the 16 mice were eliminated due to abnormal estrous cycling, and two were eliminated because they did not explore objects. As a group, the mice recognized the novel object location. Fig 7B shows that the mice spent 44.2% of the total exploration time exploring object 2 in the T1 trial. One-sample t-test revealed that this was not significantly different from chance (p=0.20). In the T2 trial, after object 2 was moved, the mice spent 67.8% of the total object exploration time exploring object 2. A one-sample t-test showed that this was significantly different from chance (p<0.005), indicating that the mice preferably explored the object in a novel location (object 2) rather than the object in a familiar location (object 1). Performance on the task was compared across the cycle using the T2 fraction (Fig. 7C). Repeated-measures ANOVA with cycle phase as the independent factor revealed no significant effect of cycle phase (F(2,0.027)=0.139, p=0.8712). To exclude differences in non-mnemonic performance factors that could mask cycle effects, total distance traveled and total object exploration during the T1 trail was compared across the cycle (data not shown). Repeated-measures ANOVA no significant effect of cycle phase on these parameters. Finally, to confirm that repeated testing did not alter performance on the task, T2 fraction was analyzed using a repeated-measures ANOVA with test number as the within-factor (Fig. 7D). There was no significant effect of test number on T2 fraction (F(2,0.056)=0.292, p=0.7501).

Figure 7.

Performance of female mice on an object placement test of 30-minute spatial memory retention is not affected by estrous cycle phase. A, Schematic diagram shows the position of objects during the sample trial (T1) and recognition trial 30 minutes later (T2), with object 2 in a new location. B, Mice explored the object in a novel location significantly more than chance during the recognition trial. The graphs show amount of time spent exploring object 2 during the sample (T1) trial and recognition (T2) trial as a percentage of total time spent exploring both objects during each trial. *p<0.005 relative to chance (0.5). C, Performance on the task was not affected by cycle phase. The graph shows amount of time spent exploring object 2 during the recognition (T2) trials as a percentage of total object exploration time during proestrus, estrus and diestrus. D, Performance was not affected by repeated testing. Graph shows total exploration time during the (T1) trial for the first, second and third tests conducted. No significant differences were found between groups. n=10 mice, each tested in proestrus, estrus, and diestrus.

Discussion

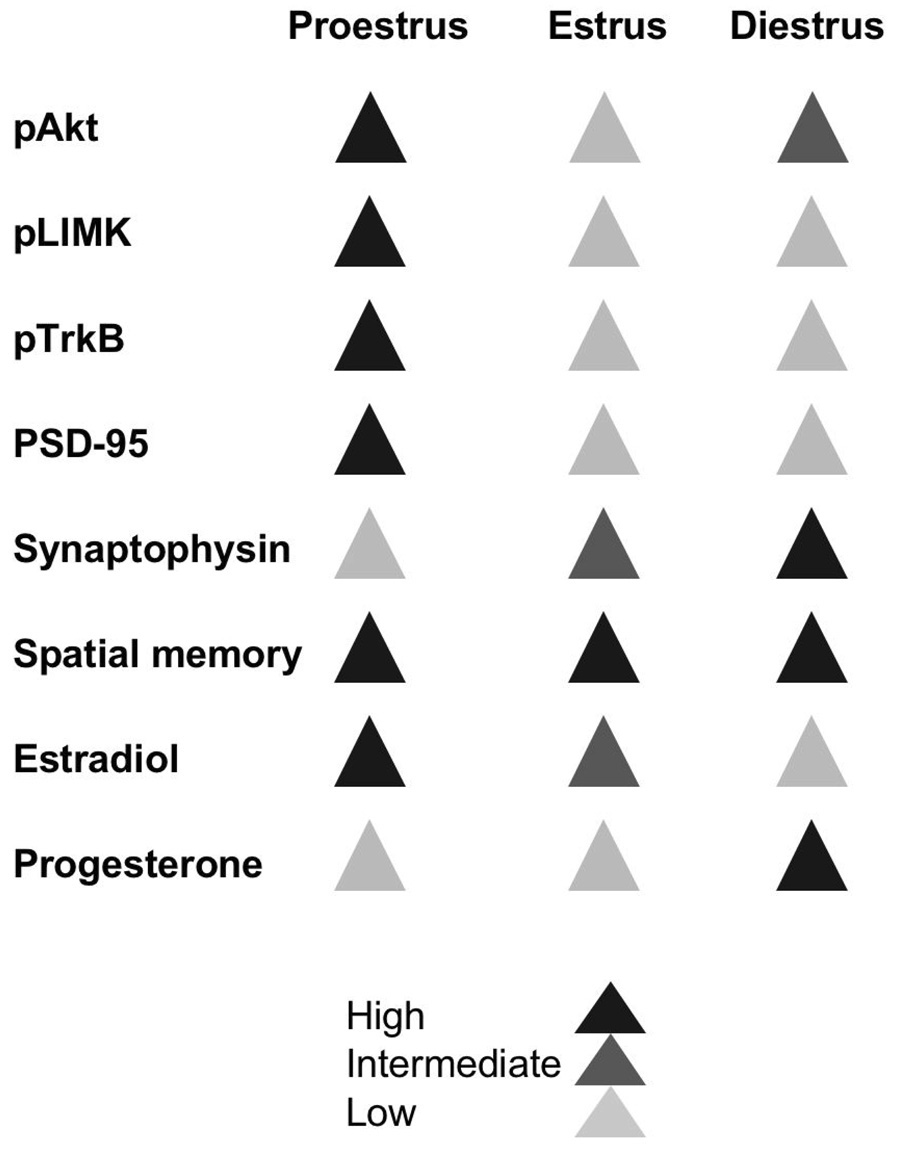

The current study is the first investigation to our knowledge of estrous cycle regulation of estradiol-sensitive signaling pathways in the mouse hippocampal formation. The findings are summarized in Figure 8, which correlates the observed fluctuation in hippocampal signaling and synaptic protein expression with circulating steroid levels. Circulating estradiol levels increase rapidly between the late diestrus and early proestrus phases of the cycle, and fall rapidly during the estrus phase in the mouse (Walmer et al., 1992). The signaling molecules Akt, LIMK, and TrkB were activated during the high-estradiol phases of proestrus. Expression of PSD-95 was also highest during this phase, while synaptophysin showed highest expression during the high-progesterone phase of diestrus. Cycle phase did not modulate spatial memory as assessed using the object placement test. Interpretations and implications of the results for estradiol modulation of hippocampal function are discussed below.

Figure 8.

Summary diagram shows levels of pAkt-, pLIMK-, pTrkB-, synaptophysin-, and PSD-95-IR as well as spatial memory across the estrous cycle of the mouse in comparison to known fluctuations of circulating estradiol and progesterone.

Activation of Akt and LIMK fluctuates predictably across the estrous cycle

The proestrus increase in pAkt- and pLIMK-IR in the hippocampal formation demonstrated in this study is consistent with their activation by estradiol, as demonstrated in the NG108-15 cell line (Akama and McEwen, 2003, Yuen, 2006). It is also consistent with the modulation of pAkt-IR in the CA1 region during the rat estrous cycle (Znamensky et al., 2003). In the current study, the fluctuation of pAkt- and pLIMK-IR across the cycle occurred throughout the dorsal hippocampal formation, consistent with our previous demonstration that estradiol increases synaptic protein expression in the dorsal hippocampal formation of mice (Li et al., 2004). Although the methodology used in this study does not distinguish between increased activation or expression of LIMK and Akt, in vitro studies suggest that estradiol activates these pathways in neurons without altering the level of Akt or LIMK expression (Akama and McEwen, 2003, Yuen, 2006). Our findings suggest that the modulation of these pathways by endogenous estradiol may contribute to fluctuations of spine and synapse dynamics, and behavior associated with ovarian cycles.

In the NG108-15 cells, LIMK is downstream of Akt in the PI3K pathway (Yuen, 2006). Because these molecules are involved in the same signaling pathway, it is not surprising that Akt and LIMK are both activated during proestrus. However, while pLIMK-IR remains low during estrus and diestrus, pAkt-IR increases slightly (but significantly) during diestrus. It is possible that progesterone plays a role in this diestrus increase in Akt activity. Progesterone levels begin to rise during late estrus, peak during diestrus, and fall again during proestrus (Walmer et al., 1992). Progesterone precipitates the decrease in spine density on CA1 pyramidal cells that occurs after a decline in estradiol levels in the rat (Woolley and McEwen, 1993). A few reports indicate that progestins can rapidly activate Akt in breast, endometrial, and cerebral cortical cells, through cross-talk with estrogen receptors (Ballare et al., 2006, Kaur et al., 2007).

TrkB activation fluctuates across the estrous cycle

The increase in pTrkB-IR in the dorsal hippocampal formation during proestrus demonstrated in this study is consistent with TrkB activation by estradiol. As mentioned earlier, estradiol may influence TrkB activation by upregulating the expression of its ligand, BDNF. Estradiol increases BDNF mRNA and protein expression in the hippocampal formation (Gibbs, 1998, Jezierski and Sohrabji, 2001, Scharfman et al., 2003, Zhou et al., 2005), which would presumably result in increased secretion of BDNF and signaling through TrkB receptors in hippocampal cells. A putative estrogen response element (ERE) has been identified in the rat BDNF gene (Sohrabji et al., 1995) whose sequence is preserved in mouse and human that binds estrogen receptor-ligand complexes in vitro. This suggests that classic genomic signaling through nuclear estrogen receptors may increase BDNF transcription. Nuclear ERα that could mediate this process is found in hippocampal interneurons (Milner et al., 2001, McEwen and Milner, 2007). Alternatively, estradiol may induce BDNF transcription through the cAMP response element (CRE) in the BDNF promotor via estrogen-dependent phosphorylation of the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) (Lee et al., 2004, Szego et al., 2006). It is possible that estradiol also increases TrkB expression in neurons. In the hypothalamus, estradiol upregulates TrkB to induce axonal outgrowth in neurons of the ventromedial nucleus (Carrer et al., 2003, Brito et al., 2004).

Despite the strong evidence for estradiol induction of BDNF in the hippocampal formation, the temporal characteristics of the fluctuation of TrkB signaling across the estrous cycle presented in this study suggest that estradiol activates TrkB rapidly through molecular interactions at the plasma membrane. In the rodent estrous cycle, circulating estradiol rises sharply overnight to peak on the day of proestrus in the rodent estrous cycle. In cells transfected with an ERE-luciferase reporter gene, 12 hours of estradiol treatment is required before detectable luciferase production (Gottfried-Blackmore et al., in press). In cultured neurons, investigators typically look for estradiol-mediated gene transcription 16 or more hours after treatment (Vasudevan et al., 2001). Therefore, in proestrus, at the time of highest pTrkB IR, estradiol has likely not been elevated for the necessary amount of time to promote BDNF transcription, release, and action through BDNF receptors at target cells. Consistent with the idea that estradiol acts to enhance TrkB signaling through a nongenomic mechanism, the time course of TrkB activation observed in this study is similar to the time course of LIMK and Akt activation, which are rapidly activated by estradiol through a presumably nongenomic mechanism. Although this evidence does not rule out estradiol-mediated activation of BDNF and/or TrkB transcritpion, it encourages investigation of an independent interaction between TrkB and estrogen receptors at the plasma membrane. Transactivation of TrkB by G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) has been reported (Lee et al., 2002), and estradiol may activate GPCRs or other growth factor receptors that could potentially mediate this cross-talk in hippocampal neurons (Lee et al., 2002, Levin, 2005, Bologa et al., 2006).

The present findings, although consistent with the in vivo literature showing that estradiol increases BDNF expression in the hippocampus, contrast with an in vitro study showing that estradiol decreases secreted BDNF in primary hippocampal cultures (Murphy et al., 1998). This decrease in BDNF permitted the estradiol-induced increase in dendritic spine density on these neurons by decreasing the activity of inhibitory interneurons in the culture (Murphy et al., 1998). The difference between these findings and our study suggests that estradiol modulates the BDNF system locally, with the overall effect favoring increased excitability of hippocampal pyramidal cells. The in vivo relevance of the in vitro work by Murphy et al. is unknown, but their findings suggest that further investigation of the interaction between estradiol and BDNF/TrkB will require examination at the level of individual cell types. Moreover, it will be important to assess whether BDNF/TrkB signaling is important for the execution of estradiol effects on hippocampal-dependent behavior.

PSD-95 and synaptophysin are differentially modulated by the estrous cycle

In ovariectomized mice, six days of estradiol replacement increases the expression of the postsynaptic proteins spinophilin and PSD-95, and the presynaptic protein syntaxin, throughout the dorsal hippocampus of the mouse (Li et al., 2004). In rats, estradiol treatment also increases the expression of these proteins, in addition to the presynaptic vesicle protein synaptophysin, in the CA1 stratum radiatum (Brake et al., 2001). Our finding that PSD-95 expression increased during proestrus is consistent with these studies. That the estrous cycle modulates PSD-95 expression in the same manner as the LIMK signaling molecule suggests a rapid effect of estradiol. Indeed, rapid estradiol-mediated upregulation of PSD-95 translation has been demonstrated in the NG108-15 cell line (Akama and McEwen, 2003). This suggests that endogenous estradiol also regulates PSD-95 translation in the mouse hippocampal formation. Given the role of PSD-95 in the formation and maintenance of functional dendritic spines and synapses (El-Husseini et al., 2000, Ehrlich et al., 2007), estradiol effects on PSD-95 expression may be important for its downstream modulation of hippocampal function.

The finding that synaptophysin IR was elevated during diestrus was surprising, given that exogenous estradiol administration increases synaptophysin expression in rat hippocampus after 48 hours (Brake et al., 2001) and in mouse hippocampus after chronic administration (Fernandez and Frick, 2004). Estradiol may increase synaptophysin expression through a genomic action too slow to detect during proestrus. Future experiments in ovariectomized animals administered estradiol at various time points before tissue collection would clarify the time course of estradiol action on the expression of specific pre- and post-synaptic proteins. In addition, examination of estradiol and cycle effects on synaptophysin mRNA and protein would clarify whether estradiol influences synaptophysin expression through a transcriptional or translational mechanism.

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of changes in synaptic protein expression across the estrous cycle in either mouse or rat. However, we cannot draw conclusions about the relationship between our findings and dendritic spine density, as no studies have specifically examined hippocampal dendritic spine density across the estrous cycle in mice. Future studies should examine the relationship between estradiol-mediated changes in synaptic protein expression and dendritic spine density in the hippocampal formation.

Estrous cycle modulates synaptic protein expression and signaling throughout the hippocampal formation

In the rat, studies of estradiol induction of dendritic spine formation and synaptic protein expression have largely concentrated on the CA1 region, where estradiol increases dendritic spine density. However, recent work has demonstrated that in the mouse, estradiol increases the expression of several synaptic proteins throughout the hippocampal formation (Li et al., 2004). Thus it is not surprising that, in the current study, estrous cycle modulated TrkB, LIMK, and Akt signaling as well as PSD-95 and synaptophysin expression not just in the CA1 region, but throughout the hippocampal formation. These findings imply that estradiol may modulate several distinct anatomical pathways in the hippocampal formation of the female mouse, but the implications of this for hippocampal function are not yet clear. In contrast to the widespread effects in the hippocampal formation, estrous cycle did not modulate any of the examined endpoints in the somatosensory cortex. This implies that the observed estrous cycle variation in signaling and synaptic protein expression is not a nonspecific effect of global alterations in brain metabolism or cerebral flood flow over the cycle, but rather, a specific effect of cycle phase on steroid-sensitive brain regions including the hippocampal formation.

Estrous cycle does not affect short-term spatial memory in mice

The object placement task was used here for the assessment of spatial memory because estradiol administration to female rats and mice enhances performance on this task (Luine et al., 2003, Li et al., 2004). The short latency of 30 minutes between sample and recognition trials enabled completion of a testing cycle in the same phase of the estrous cycle. Repeated testing did not affect performance on this task. Estrous cycle phase did not alter performance on the task. Non-mnemonic factors such as motivation to explore objects and mobility also did not fluctuate across the cycle.

Only one other study to our knowledge examined spatial memory across the estrous cycle in C57BL/6 mice (Frick and Berger-Sweeney, 2001). This group used a one-day water maze protocol to evaluate spatial memory within each cycle phase. The task tested memory acquisition (working memory) and retention (reference memory) of the location of an underwater escape platform. Both acquisition and 30-minute retention was impaired during estrus relative to proestrus and metestrus (the transition between estrus and diestrus). Numerous differences between the design of this study and ours may account for the conflicting results. First, a comparative study of performance on the Morris water maze between male rats and mice suggested that mice use nonspatial strategies to solve the water maze task (Frick et al., 2000). If this is the case, the water maze task may assay the function of brain areas other than hippocampus, and this may explain its differential sensitivity to estrous cycle phase (Korol, 2004). The selection of a behavioral task is important because the effects of estradiol on learning and memory vary according to the behavioral task as well as the dose and timing of hormone administration (Korol and Kolo, 2002, Luine et al., 2003). Thus, because our study focused on the hippocampal formation, we selected a task that relies heavily on hippocampal function (Good et al., 2007).

Second, in the current study, mice in every cycle phase explored the novel object location more than the familiar location, indicating a preference for the novel location in all cycle phases. Therefore the task we used was too easy to detect fluctuations in performance across the estrous cycle. In contrast, this task is sensitive to the total absence of estrogens, since in previous studies, ovariectomized mice and rats administered vehicle did not discriminate between novel and familiar object locations, while estrogen-treated animals preferred the novel location (Luine et al., 2003, Li et al., 2004). Our findings suggest that intact mice can detect a novel object location regardless of estrous cycle phase when this task is performed using a 30-minute delay between T1 and T2 trials.

Besides the behavioral task and degree of estrogen deprivation, the effects of stress and interaction between stress and estradiol must be considered when interpreting the findings of this and other studies. In particular, stress and estradiol interact to modulate behavior and have opposite effects on hippocampal CA1 dendritic spine density in female rats (Wood and Shors, 1998, Shors et al., 2004). Therefore the relative stress imposed by different behavioral tasks may in part account for discrepant findings. For example, water maze tests are commonly regarded as more stressful tasks than dry maze and open-field tests in mice. We sought to reduce the confounding effect of stress on our findings by choosing a relatively low-stress test, the object placement test. This may have contributed to the differences between our results and those from a previous study employing a water maze test (Frick and Berger-Sweeney, 2001). On the other hand, daily handling with vaginal smears and any sort of behavioral testing are moderately stressful events for animals, even when performed repeatedly. Because of this, we can never fully separate the effects of estrous cycle from their interaction with the stress of these procedures on any of our results, including behavior and immunocytochemsitry.

Significance for Translational Research

Psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety afflict millions of women in the U.S. each year. The prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in the general population is estimated above 25%, and some of these disorders afflict more women than men (Kessler et al., 2005). Several affective disorders are associated with the menstrual cycle, while the onset and symptoms of others may be modulated by ovarian steroids (Seeman, 1997, Aloysi et al., 2006, Cohen et al., 2006). The investigation of estrous cycle modulation of hippocampal function may therefore directly translate into better understanding of affective disorders associated with the menstrual cycle and hormone use in women. One such disorder is premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a well-characterized mood disorder that affects up to 8% of women in the United States (Halbreich et al., 2003). Women with PMDD have a distinct pattern of hippocampal activation across the menstrual cycle that may relate to the mood and cognitive symptoms they experience (Protopopescu, 2006). Understanding how natural fluctuations in ovarian steroids affect brain function is a crucial step in defining the mechanism of this disorder and developing rational treatment options.

The conscientious design of pharmacological estrogens also requires better knowledge of how these drugs affect brain function. Estrogens and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are indicated for a variety of disorders including infertility, reproductive cancers, contraception, and menopausal symptoms. Although hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is often prescribed for the treatment of menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes and dyspareunia, its role in the treatment or prevention of cognitive decline and mood disorders in this age group is still unclear (Hickey et al., 2005, Aloysi et al., 2006). Understanding the way in which natural estrogens affect brain function in healthy, young animals is the first step in defining age-related changes in response to hormones, and will enable identification of the most promising synthetic estrogens to protect brain health.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that endogenous fluctuations of ovarian steroids modulate hippocampal nongenomic steroid hormone signaling and synaptic protein expression in female C57BL6 mice. The findings suggest that the endogenous surge in estradiol during proestrus may directly activate the PI3K pathway (with downstream targets Akt, LIMK, and PSD-95) and the BDNF/TrkB system in this cycle phase. Future work using gonadectomy and hormone treatment and mice with different genotypes will clarify the direct role of ovarian steroids in these findings. Because the hippocampal formation plays an important role in both cognitive function and normal or disordered mood, this study marks an important step in elucidating the mechanism of cycle- and ovarian steroid-associated neurologic and psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This work was supported by NIH grants NS007080 (B.S.M.), GM07739 (J.L.S.), MH082528 (J.L.S.), DA08259 (T.A.M.) and HL18974 (T.A.M.).

Abbreviations

- ER

estrogen receptor

- LIMK

LIM Kinase

- PSD-9

post-synaptic density 95

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- PB

phosphate buffer

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- TS

tris saline

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- IR

immunoreactivity

- T1

sample trial of the object placement task

- T2

recognition trial of the object placement task

- ROD

relative optical density

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ERE

estrogen response element

- CRE

cAMP response element

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- PMDD

premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- HRT

hormone replacement therapy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akama KT, McEwen BS. Estrogen stimulates postsynaptic density-95 rapid protein synthesis via the Akt/protein kinase B pathway. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2333–2339. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02333.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloysi A, Van Dyk K, Sano M. Women's cognitive and affective health and neuropsychiatry. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:967–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arevalo JC, Waite J, Rajagopal R, Beyna M, Chen ZY, Lee FS, Chao MV. Cell survival through Trk neurotrophin receptors is differentially regulated by ubiquitination. Neuron. 2006;50:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballare C, Vallejo G, Vicent GP, Saragueta P, Beato M. Progesterone signaling in breast and endometrium. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;102:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologa CG, Revankar CM, Young SM, Edwards BS, Arterburn JB, Kiselyov AS, Parker MA, Tkachenko SE, Savchuck NP, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER. Virtual and biomolecular screening converge on a selective agonist for GPR30. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nchembio775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brake WG, Alves SE, Dunlop JC, Lee SJ, Bulloch K, Allen PB, Greengard P, McEwen BS. Novel target sites for estrogen action in the dorsal hippocampus: an examination of synaptic proteins. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1284–1289. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.3.8036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito VI, Carrer HF, Cambiasso MJ. Inhibition of tyrosine kinase receptor type B synthesis blocks axogenic effect of estradiol on rat hypothalamic neurones in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:331–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrer HF, Cambiasso MJ, Brito V, Gorosito S. Neurotrophic factors and estradiol interact to control axogenic growth in hypothalamic neurons. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1007:306–316. doi: 10.1196/annals.1286.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang PC, Aicher SA, Drake CT. Kappa opioid receptors in rat spinal cord vary across the estrous cycle. Brain Res. 2000;861:168–172. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao MV. Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nrn1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, Otto MW, Harlow BL. Risk for New Onset of Depression During the Menopausal Transition: The Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:385–390. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Astous M, Mendez P, Morissette M, Garcia-Segura LM, Di Paolo T. Implication of the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/protein kinase B signaling pathway in the neuroprotective effect of estradiol in the striatum of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1492–1498. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, Hen R. Young and excitable: the function of new neurons in the adult mammalian brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Klein M, Rumpel S, Malinow R. PSD-95 is required for activity-driven synapse stabilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4176–4181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609307104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Husseini AE, Schnell E, Chetkovich DM, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. PSD-95 involvement in maturation of excitatory synapses. Science. 2000;290:1364–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez SM, Frick KM. Chronic oral estrogen affects memory and neurochemistry in middle-aged female mice. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:1340–1351. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.6.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick KM, Berger-Sweeney J. Spatial reference memory and neocortical neurochemistry vary with the estrous cycle in C57BL/6 mice. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:229–237. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.115.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick KM, Stillner ET, Berger-Sweeney J. Mice are not little rats: species differences in a one-day water maze task. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3461–3465. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200011090-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea LA. Gonadal hormone modulation of neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of adult male and female rodents. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB. Levels of trkA and BDNF mRNA, but not NGF mRNA, fluctuate across the estrous cycle and increase in response to acute hormone replacement. Brain Res. 1998;810:294. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00945-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Burgos I, Alejandre-Gomez M, Cervantes M. Spine-type densities of hippocampal CA1 neurons vary in proestrus and estrus rats. Neurosci Lett. 2005;379:52–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good MA, Barnes P, Staal V, McGregor A, Honey RC. Context- but not familiarity-dependent forms of object recognition are impaired following excitotoxic hippocampal lesions in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:218–223. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried-Blackmore A, Croft G, Clark J, McEwen BS, Jellinck PH, Bulloch K. Characterization of a Cerebellar Granule Progenitor cell line, EtC.1, and its Responsiveness to 17-beta-Estradiol. Brain Res. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.071. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Woolley CS, Frankfurt M, McEwen BS. Gonadal steroids regulate dendritic spine density in hippocampal pyramidal cells in adulthood. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1286–1291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01286.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, Kahn LS. The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD) Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28 Suppl 3:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Janssen WG, Tang Y, Roberts JA, McKay H, Lasley B, Allen PB, Greengard P, Rapp PR, Kordower JH, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Estrogen increases the number of spinophilin-immunoreactive spines in the hippocampus of young and aged female rhesus monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:540–550. doi: 10.1002/cne.10837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Rapp PR, Leffler AE, Leffler SR, Janssen WG, Lou W, McKay H, Roberts JA, Wearne SL, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Estrogen alters spine number and morphology in prefrontal cortex of aged female rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2571–2578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3440-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey M, Davis SR, Sturdee DW. Treatment of menopausal symptoms: what shall we do now? Lancet. 2005;366:409–421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo L, Straub RE, Schmidt PJ, Shi K, Vakkalanka R, Weinberger DR, Rubinow DR. Risk for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder Is Associated with Genetic Variation in ESR1, the Estrogen Receptor Alpha Gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelks KB, Wylie R, Floyd CL, McAllister AK, Wise P. Estradiol targets synaptic proteins to induce glutamatergic synapse formation in cultured hippocampal neurons: critical role of estrogen receptor-alpha. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6903–6913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0909-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezierski MK, Sohrabji F. Neurotrophin expression in the rep roductively senescent forebrain is refractory to estrogen stimulation. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of Neural Science. McGraw-Hill Publishing Co.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur P, Jodhka PK, Underwood WA, Bowles CA, de Fiebre NC, de Fiebre CM, Singh M. Progesterone increases brain-derived neuroptrophic factor expression and protects against glutamate toxicity in a mitogen-activated protein kinase-and phosphoinositide-3 kinase-dependent manner in cerebral cortical explants. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2441–2449. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korol DL. Role of estrogen in balancing contributions from multiple memory systems. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;82:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korol DL, Kolo LL. Estrogen-induced changes in place and response learning in young adult female rats. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:411–420. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korol DL, Malin EL, Borden KA, Busby RA, Couper-Leo J. Shifts in preferred learning strategy across the estrous cycle in female rats. Horm Behav. 2004;45:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagace DC, Fischer SJ, Eisch AJ. Gender and endogenous levels of estradiol do not influence adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Hippocampus. 2007;17:175–180. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FS, Rajagopal R, Chao MV. Distinctive features of Trk neurotrophin receptor transactivation by G protein-coupled receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Campomanes CR, Sikat PT, Greenfield AT, Allen PB, McEwen BS. Estrogen induces phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element binding (pCREB) in primary hippocampal cells in a time-dependent manner. Neuroscience. 2004;124:549–560. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1951–1959. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Brake WG, Romeo RD, Dunlop JC, Gordon M, Buzescu R, Magarinos AM, Allen PB, Greengard P, Luine V, McEwen BS. Estrogen alters hippocampal dendritic spine shape and enhances synaptic protein immunoreactivity and spatial memory in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2185–2190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307313101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luine VN, Jacome LF, Maclusky NJ. Rapid enhancement of visual and place memory by estrogens in rats. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2836–2844. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLusky NJ, Luine VN, Hajszan T, Leranth C. The 17alpha and 17beta isomers of estradiol both induce rapid spine synapse formation in the CA1 hippocampal subfield of ovariectomized female rats. Endocrinology. 2005;146:287–293. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Milner TA. Hippocampal formation: Shedding light on the influence of sex and stress on the brain. Brain Res Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Tanapat P, Weiland NG. Inhibition of dendritic spine induction on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons by a nonsteroidal estrogen antagonist in female rats. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1044–1047. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.3.6570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Zhang Y, Tregoubov V, Falls DL, Jia Z. Regulation of spine morphology and synaptic function by LIMK and the actin cytoskeleton. Rev Neurosci. 2003;14:233–240. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2003.14.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Zhang Y, Tregoubov V, Janus C, Cruz L, Jackson M, Lu WY, MacDonald JF, Wang JY, Falls DL, Jia Z. Abnormal spine morphology and enhanced LTP in LIMK-1 knockout mice. Neuron. 2002;35:121–133. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, Ayoola K, Drake CT, Herrick SP, Tabori NE, McEwen BS, Warrier S, Alves SE. Ultrastructural localization of estrogen receptor beta immunoreactivity in the rat hippocampal formation. J Comp Neurol. 2005;491:81–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, McEwen BS, Hayashi S, Li CJ, Reagan LP, Alves SE. Ultrastructural evidence that hippocampal alpha estrogen receptors are located at extranuclear sites. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429:355–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DD, Cole NB, Segal M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mediates estradiol-induced dendritic spine formation in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11412–11417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press, An Imprint of Elsevier; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pedram A, Razandi M, Levin ER. Nature of functional estrogen receptors at the plasma membrane. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1996–2009. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Kurucz OS, Milner TA. Morphometry of a peptidergic transmitter system: dynorphin B-like immunoreactivity in the rat hippocampal mossy fiber pathway before and after seizures. Hippocampus. 1999;9:255–276. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:3<255::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protopopescu X. Laboratory of Neuroendocrinology), vol. Ph.D. New York: The Rockefeller University; 2006. Functional and Structural MRI of the Menstrual Cycle and PMDD; p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp PR, Morrison JH, Roberts JA. Cyclic estrogen replacement improves cognitive function in aged ovariectomized rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5708–5714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05708.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg L, Park S. Verbal and spatial functions across the menstrual cycle in healthy young women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:835–841. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom NJ, Williams CL. Spatial memory retention is enhanced by acute and continuous estradiol replacement. Horm Behav. 2004;45:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, Maclusky NJ. Similarities between actions of estrogen and BDNF in the hippocampus: coincidence or clue? Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, Maclusky NJ. Estrogen and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in hippocampus: Complexity of steroid hormone-growth factor interactions in the adult CNS. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2006a doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, MacLusky NJ. The influence of gonadal hormones on neuronal excitability, seizures, and epilepsy in the female. Epilepsia. 2006b;47:1423–1440. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, Mercurio TC, Goodman JH, Wilson MA, MacLusky NJ. Hippocampal excitability increases during the estrous cycle in the rat: a potential role for brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11641–11652. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11641.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman MV. Psychopathology in women and men: focus on female hormones. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1641–1647. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.12.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ, Falduto J, Leuner B. The opposite effects of stress on dendritic spines in male vs. female rats are NMDA receptor-dependent. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:145–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.03065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabji F, Miranda RC, Toran-Allerand CD. Identification of a putative estrogen response element in the gene encoding brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11110–11114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JL, Waters EM, Romeo RD, Wood G, Milner TA, McEwen B. Uncovering the Mechanisms of Estrogen Effects on Hippocampal Function. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szego EM, Barabas K, Balog J, Szilagyi N, Korach KS, Juhasz G, Abraham IM. Estrogen induces estrogen receptor alpha-dependent cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation via mitogen activated protein kinase pathway in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in vivo. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4104–4110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0222-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasawa E, Timiras PS. Electrical activity during the estrous cycle of the rat: cyclic changes in limbic structures. Endocrinology. 1968;83:207–216. doi: 10.1210/endo-83-2-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CD, Bagnara JT. General Endocrinology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan N, Kow LM, Pfaff DW. Early membrane estrogenic effects required for full expression of slower genomic actions in a nerve cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12267–12271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221449798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmer DK, Wrona MA, Hughes CL, Nelson KG. Lactoferrin expression in the mouse reproductive tract during the natural estrous cycle: correlation with circulating estradiol and progesterone. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1458–1466. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.3.1505477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood GE, Shors TJ. Stress facilitates classical conditioning in males, but impairs classical conditioning in females through activational effects of ovarian hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4066–4071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, Gould E, Frankfurt M, McEwen BS. Naturally occurring fluctuation in dendritic spine density on adult hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1990;10:4035–4039. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-04035.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Estradiol mediates fluctuation in hippocampal synapse density during the estrous cycle in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2549–2554. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02549.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Roles of estradiol and progesterone in regulation of hippocampal dendritic spine density during the estrous cycle in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:293–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildrim M, Janssen WG, Tabori NE, Adams MM, Yuen G, Akama K, McEwen B, Milner TA, Morrison JH. Effects of Estrogen and Aging on Distribution of pLIMK in CA1 Region of Rat Hippocampus. Proceedings of the Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting; Washington, D.C.. 2005. pp. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen G. Laboratory of Neuroendocrinology), vol. Ph.D. New York: The Rockefeller University; 2006. Estrogen action on actin dynamics: Mechanism for Dendritic Spine Remodeling in the Adult Hippocampus; p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Zhang H, Cohen RS, Pandey SC. Effects of estrogen treatment on expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cAMP response element-binding protein expression and phosphorylation in rat amygdaloid and hippocampal structures. Neuroendocrinology. 2005;81:294–310. doi: 10.1159/000088448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Znamensky V, Akama KT, McEwen BS, Milner TA. Estrogen levels regulate the subcellular distribution of phosphorylated Akt in hippocampal CA1 dendrites. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2340–2347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02340.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]