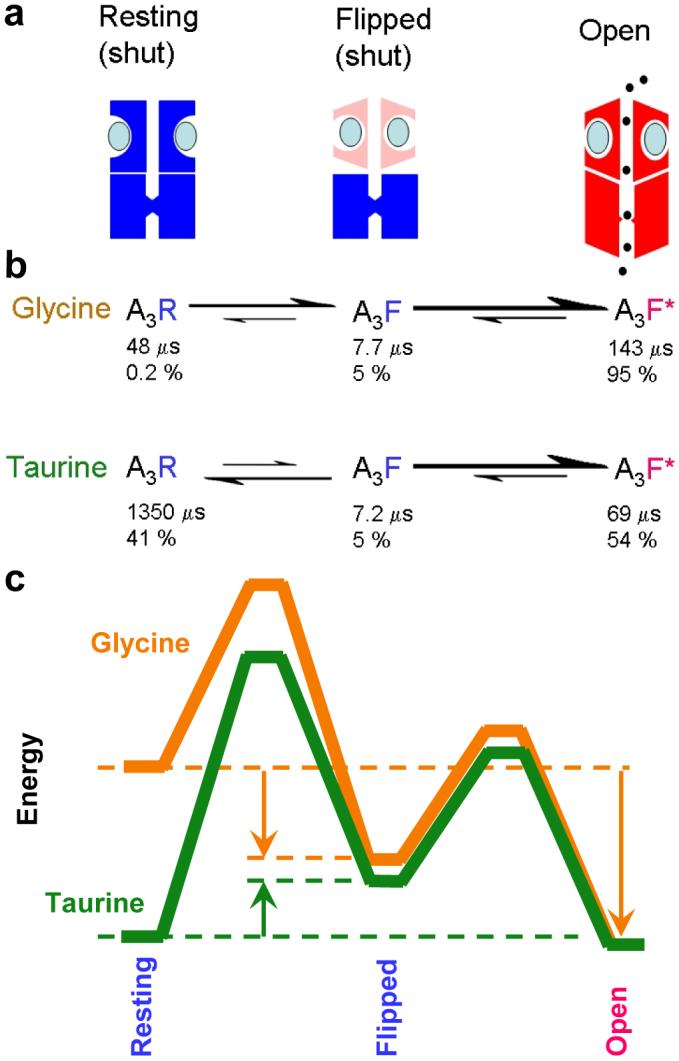

Figure 3.

Activation of the glycine channel by the full agonist glycine and the partial agonist taurine.

a, The three states of the fully-saturated receptor. The resting (shut) channel changes conformation to reach a partially-activated state (‘flipped’), still shut, but with increased affinity for the agonist (blue ellipses). It is from this flipped state that the channel can open (red, right). b, The reaction rates for channel activation by glycine and taurine differ largely in the first step, the flipping. Relative rates are indicated by the size of arrows. The diagram shows also the mean lifetime of each state (μs) and the proportion of time (percent) spent by a bound channel in each of the states at equilibrium. A channel occupied by glycine doesn’t stay long in the resting state, but quickly flips. When taurine is bound, the channel takes a long time to flip, so it spends much more time in the closed resting state. Once the channel has reached the flipped intermediate state, it opens quickly, regardless of which agonist is bound. The probability of opening, rather than unflipping, is over 96% for both agonists, so a burst of many openings results. c, An energy diagram for the three states of the saturated receptor, for full agonist (glycine, orange) and partial agonist (taurine, green). Again, the difference lies largely in the resting-flipped transition. As indicated by arrows, the transition from resting to flipped is downhill for glycine, but uphill for taurine. The overall transition from resting to open is very downhill for glycine, but almost level for taurine, as expected from the maximum response of about 54% open. The calculations used a frequency factor27 of 107 s−1 and the lines are shifted vertically so they meet at the open state., See also Supplementary movie.