Summary

This case is the first report of a patient who had phenobarbital (PB) withdrawal seizures after having been seizure-free for three years following temporal lobe surgery. The patient had been taking PB for 14 years when a gradual taper of PB was started. When PB was at 60 mg/d, a titration of lamotrigine (LTG) was started. However, typical complex seizures occurred when the patient was on PB 60 mg/d, along with LTG 25 mg/d. PB was increased back to 90 mg/d and levetiracetam (LEV) was titrated. Seizures appeared when the patient was on PB 30 mg/d and LEV 750 mg BID and continued for three weeks after PB was stopped and the patient was on LEV 1000 mg BID. For the following six months, her aura frequency remained elevated in comparison to her baseline aura of two auras per month for the previous year before the start of the PB taper. She was followed for 24 months after her last PB withdrawal seizure. During the last eight months, her aura frequency returned to her baseline. As suggested by animal studies, the PB withdrawal seizures and increase in aura frequency in this patient may be explained by changes in her levels of GABAA receptor subunits.

Keywords: Phenobarbital, withdrawal seizures, Auras, temporal lobe epilepsy, simple partial seizures, GABAA receptor

Introduction

Because of the increased risk of fractures, osteopenia, and osteoporosis associated with long-term phenobarbital (PB) therapy [1–3], we decided to slowly withdraw the patient from PB after she had been seizure-free for three years following right anterior temporal lobectomy. A previous study reported an increase seizure frequency in patients tapered from PB or primidone, while stabilized on another anti-epileptic drug (AED) [4]. Our report is the first study in a patient who had been seizure-free for several years before the initiation of the PB taper and who once again became seizure-free after full PB discontinuation.

PB withdrawal in rodents has been associated with a decrease in the number of GABA A receptors (GABAAR) [5]. There was a 45% decrease in the α1 subunit protein levels of the GABAAR in the whole hippocampus in rat pups that had been exposed to PB for 30 days in comparison to vehicle-treated controls [6]. This finding suggests that chronic PB exposure results in changes in the GABAAR and that change in the expression of the subunits of the GABAAR may correlate with the presence of PB withdrawal seizures.

Case report

A 51-year old female patient, seizure-free for three years following removal of a cavernous angioma of her right anterolateral temporal lobe, had been taking PB for 11 years before surgery and was maintained on PB 150 mg/d for 3 years after surgery. We decided to taper PB and to replace it with an anticonvulsant not associated with the above risks. The patient kept accurate daily records of auras and seizures on a long-term continuous basis.

Because PB induces the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 family of enzymes that glucuronidate lamotrigine (LTG), we decided to taper PB from 150 mg/d to 60 mg/d before initiating the LTG titration. The PB dose was reduced by 30 mg every three weeks. For the 16 weeks preceding the initiation of the PB taper, the patient averaged two psychic auras per month, which was the baseline that she had maintained for the previous year, but she remained seizure free.

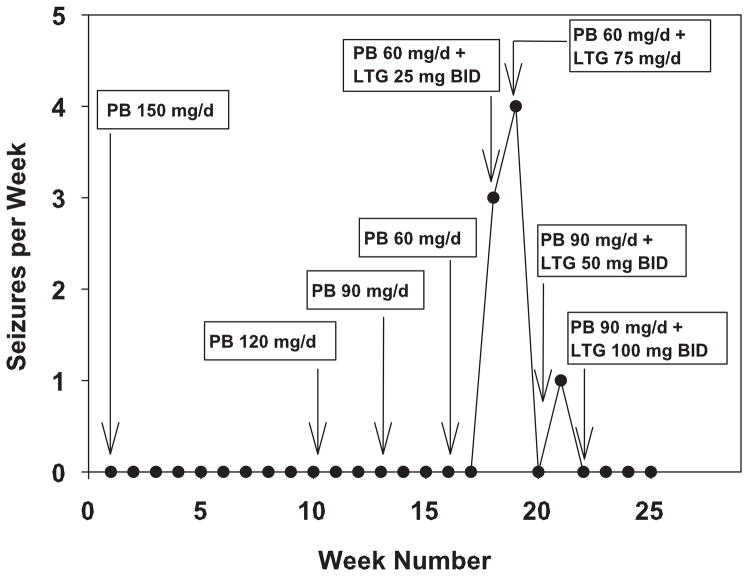

When the patient had tapered PB to 60 mg/d, the LTG titration was initiated. LTG was increased by 25 mg per week until a dose of 100 mg BID was achieved. However, as shown in Fig. 1, when the patient reached doses of PB 60 mg/d and LTG 25 mg BID, complex partial seizures occurred. At the time, it was not known whether these seizures were PB withdrawal seizures or the reinstatement of her complex partial seizures because the symptoms of these seizures were virtually identical to her preoperative seizures. Her PB blood level was 7 μg/ml when the seizures started (Fig. 1). When the patient had been seizure-free on 150 mg/d of PB, her blood level was 21μg/ml. Because of the presence of seizures, her PB dose was increased back to 90 mg/d, a dose that kept the patient seizure-free. Conversion to LTG ultimately failed because of rash.

Fig. 1.

PB withdrawal seizures as a function of the daily doses of PB and LTG. PB was tapered by 30 mg every three weeks. On the second week that the patient was on PB 60 mg/d, a LTG titration was started with the first week being a daily dose of 25 mg/d. Data are reported as the number of seizures per week.

The goal remained to switch from PB to an AED without the risks associated with an AED that induces hepatic metabolism. Five weeks after LTG was stopped, levetiracetam (LEV) was started. The patient was on PB 90 mg/d, and LEV was increased by 125 mg every five days until a dose of 500 mg BID, was obtained. The patient averaged approximately one aura per week. After the patient was taking LEV 500 mg BID, the PB taper was attempted the second time at a slower rate. PB was reduced by 15 mg every three weeks, which was half the rate of the initial PB taper. At a dose of PB 45 mg/d and LEV 500 mg BID, the frequency of auras increased. LEV was increased from 500 mg BID to 750 mg BID, while the PB taper continued. Complex partial seizures started when the patient was taking PB 30 mg/d and LEV 750 mg BID (Fig. 2). Because of the seizures, LEV was increased further to 1000 mg BID. When the patient was on PB 15 mg/d and LEV 1000 mg BID, four seizures occurred over a three-week period (Fig. 2). She had an additional four seizures during the first week after discontinuing PB. The seizures continued for three weeks after discontinuation then stopped (Fig. 2). The patient has been maintained on LEV 1000 mg BID. There have been no further seizures during 24 months of follow-up.

Fig. 2.

PB withdrawal seizures as a function of the daily doses of PB and LEV. PB was tapered by 15 mg every three weeks. The dose of LEV was increased as shown in the graph. Data are reported as the number of seizures per week.

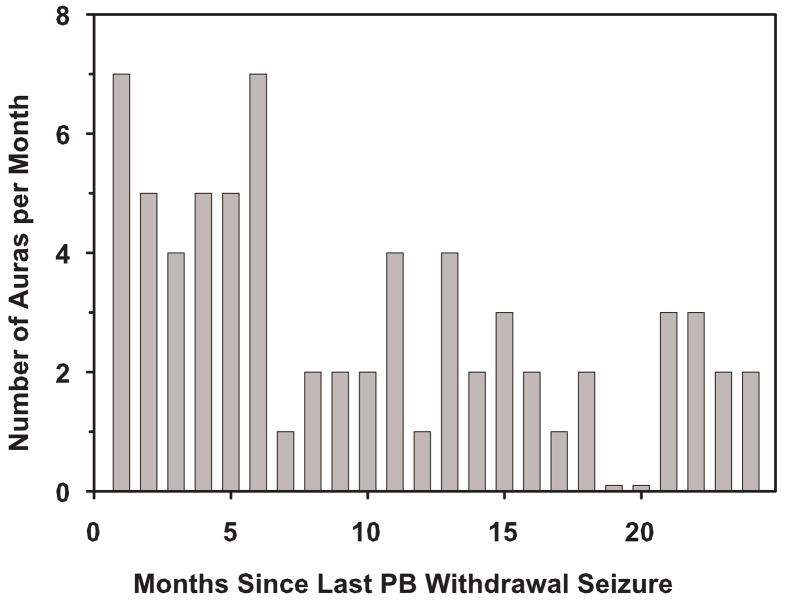

The frequency of the patient’s auras remained above her baseline of two auras per month for six months immediately following cessation of PB withdrawal seizures (Fig. 3). The patient experienced insomnia and anxiety while tapering PB. Insomnia and an increase in aura frequency were the first physical signs of PB withdrawal despite the very slow taper. Insomnia abated shortly after complete withdrawal from PB. Anxiety first occurred when the patient had tapered to PB 30 mg/d. Some anxiety remained for the same six-month period after seizure cessation, when there was an increase in aura frequency. Starting at seven months after PB cessation, her aura frequency decreased to her baseline aura frequency of two auras per month (Fig. 3) and her anxiety symptoms resolved.

Fig. 3.

Aura frequency during the 24 months after cessation of PB withdrawal seizures. After the PB withdrawal seizures had stopped, the frequency of auras was recorded. Before the PB taper, when the patient was taking PB 150 mg/d, her baseline aura frequency for more than a year was two auras per month. Data are reported as the number of auras during the previous 30 days. Data were collected for 24 months after her last PB withdrawal seizure.

Discussion

This case demonstrates a threshold for PB withdrawal seizures at 30 to 60 mg/d and cessation of withdrawal seizures following PB discontinuation. At a dose of PB 90 mg/d, the patient had a plasma PB level of 11 μg/ml (Fig. 1). Assuming clearance did not change, withdrawal seizures appeared when the PB level was 5–8 μg/ml. Withdrawal seizures were not controlled by either LTG at low dose or LEV at high dose but ceased three weeks post complete withdrawal. Although it is possible that other factors such as incomplete resection of pathologic tissue, contralateral or extratemporal involvement might be responsible for seizure reoccurrence, neither the post-operative MRI nor the pre-operative EEG, respectively, supported these possibilities. While many endogenous and exogenous stresses such as illness, hormonal changes, stress, and fatigue may trigger seizures in patients with epilepsy, the only time our patient had clinical seizures was during and immediately following the tapering of PB.

A previous study reported PB withdrawal seizures when patients with refractory seizures were being rapidly tapered from PB or primidone, while stabilized on another AED [4]. There was a tendency for the seizures rates to be the highest when the PB blood levels passed through the range of 15 to 20 μg/ml [4]. The present case demonstrates that despite a very slow PB taper over several months in a seizure-free patient, withdrawal seizures may occur for several weeks before remission. The occurrence of PB withdrawal seizures does not mean PB withdrawal will not be ultimately successful.

After the seven weeks of PB withdrawal seizures in the presence of LEV 1000 mg BID, the frequency of auras remained elevated for another six months before returning to baseline. A long period of withdrawal symptoms has been observed during the tapering of other CNS drugs that produce physical dependence. Protracted withdrawal symptoms from tapering and discontinuation of benzodiazepines have been reported [7]. Smith and Wesson [8] observed that symptoms, such as anxiety, insomnia, and paresthesia, after withdrawal from low-dose benzodiazepine typically take 6–12 months to subside completely. In our patient, it took seven months for her aura frequency to return to baseline.

Molecular changes in the GABA system probably account for many symptoms associated with PB withdrawal. Approximately 43% of the GABAAR in mammalian brain is comprised of 2 α1 subunits, 2 β2 subunits and one γ1 subunit. In humans with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) and in rodent models of TLE, there was a reduced expression of GABAAR α1 subunits and increased expression GABAAR α4 subunits in the dentate gyrus of epileptic individuals [9, 10]. Binding of the GABA agonist, [3H]muscimol, to GABAAR in rat brain homogenates was reduced by 25% in withdrawing animals for up to 10 days after chronic PB exposure [4]. This finding suggests downregulation of the GABAAR during PB withdrawal. GABA agonists are known to cause downregulation of the GABAAR through endocytosis of GABAAR via clathrin-coated pits is indicated by the interaction between GABAAR and the adapter protein AP2 and is known to require the γ2 subunit and dynamin. Endosomal GABAAR are targeted for degradation or are possibly held and recycled back to the surface with the help of Plic-1 [11]. Similarly, prolonged exposure to ethanol, which also activates the GABAAR [12], has been shown to increase the endocytic internalization of α1 subunits [13].

There was ~45% decrease in the α1 subunit protein levels of the GABAAR in the whole hippocampus in rat pups that had been exposed to PB for 30 days in comparison to vehicle-treated controls [6]. An adeno-associated virus type 2 containing the α4 subunit gene promoter has been used to drive transgene expression in dentate gyrus of rats after status epilepticus (SE). Enhanced expression of the GABAARα1 subunit in the dentate gyrus resulted in a three-fold increase in mean seizure-free time after SE and a 60% decrease in the number of rats developing recurrent seizures in the first four weeks after SE [14]. In contrast, withdrawal from a positive modulator of GABAAR activity, such as benzodiazepines, ethanol and neurosteroids, induces a decrease in the levels of the α1 subunit and an increase in the expression of the α4 subunit of the GABAAR [15]. Collectively, previous studies have shown that changes in the subunit composition of the GABAAR occur before and during PB withdrawal [6]. Based on rodent studies, a downregulation of the GABAAR, particularly the α1 subunit, would be associated with an increase in the frequency of withdrawal seizures and auras.

In conclusion, this well-documented case report demonstrates the long timeline of PB withdrawal seizures. In our patient, they began when her PB dose had been reduced by approximately 50% and were not related to speed of PB withdrawal. In addition, PB withdrawal seizures occurred for seven weeks following complete withdrawal; auras remained above baseline rate for seven months as did other common symptoms of PB withdrawal. The protracted seizures and auras may be explained by the alteration in the GABAAR subunits and the long time required for it to revert to its normal state. Withdrawing patients from PB can be done but should be done slowly. Despite seizures on withdrawal, the process may ultimately be successful.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by K05 DA00360, a NIH Senior Scientist award, from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Persson HBI, Alberts KA, Farahmand BY. Risk of extremity fractures in adult outpatients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2002;43:768–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.15801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pack AM, Morrell MJ. Epilepsy and bone health in adults. Epilepsy and Behav. 2004;5:S24–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Fracture risk associated with the use of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2004;45:1330–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.18804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theodore WH, Porter RJ, Raubertas RF. Seizures during barbiturate withdrawal: relation to blood level. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:644–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka S, Aoki K, Satoh T, Yoshida T, Kuroiwa Y. Characteristic changes of the GABAA receptor in the brain of phenobarbital-dependent and withdrawn rats. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1991;73:269–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raol YH, Zhang G, Budreck EC, Brooks-Kayal AR. Long-term effects of diazepam and phenobarbital treatment during development on GABA receptors, transporters and glutamic acid decarboxylase. Neuroscience. 2005;132:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashton H. Protracted withdrawal syndromes from benzodiazepines. J Substance Abuse Treatment. 1991;8:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(91)90023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith DE, Wesson DR. Benzodiazepine dependency syndromes. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1983;15:85–95. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1983.10472127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Rikhter TY, Coulter DA. Selective changes in single cell GABA(A) receptor subunit expression and function in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Med. 1998;10:1166–72. doi: 10.1038/2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Lin DD, Rikhter TY, et al. Human neuronal gamma-aminobutyric acid (A) receptors: coordinated subunit mRNA expression and functional correlates in individual dentate granule cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8312–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08312.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lüscher B, Keller CA. Ubiquitination, proteasomes and GABAA receptors. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E232–3. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-e232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogawski MA. Update on the neurobiology of alcohol withdrawal seizures. Epilepsy Currents. 2005;5:225–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2005.00071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlton ME, Sweetnam PM, Fitzgerald LW, Terwilliger RZ, Nestler EJ, et al. Chronic ethanol administration regulates the expression of GABAA receptor α1 and α5 subunits in ventral tegmental area and hippocampus. J Neurochem. 1997;68:121–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68010121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raol YH, Lund IV, Bandyopadhyay S, Zhang G, Roberts DS, et al. Enhancing GABAA receptor α1 subunit levels in hippocampal dentate gyrus inhibits epilepsy development in an animal model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11342–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3329-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith SS, Shen H, Gong QH, Zhou X. Neurosteroid regulation of GABAA receptors: Focus on α4 and δ subunits. Pharmacol & Ther. 2007;116:58–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]