Abstract

Bordetella (B) bronchiseptica is a common veterinary pathogen, but has rarely been implicated in human infections. Most patients with B. bronchiseptica infections are compromised clinically such as in patients with a malignancy, AIDS, malnutrition, or chronic renal failure. We experienced a case of relapsing peritonitis caused by B. bronchiseptica associated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). A 56-yr-old male, treated with CAPD due to end stage renal disease (ESRD), was admitted with complaints of abdominal pain and a turbid peritoneal dialysate. The culture of peritoneal dialysate identified B. bronchiseptica. The patient was treated with a combination of intraperitoneal antibiotics. There were two further episodes of relapsing peritonitis, although the organism was sensitive to the used antibiotics. Finally, the indwelling CAPD catheter was removed and the patient was started on hemodialysis. This is the first report of a B. bronchiseptica human infection in the Korean literature.

Keywords: Bordetella Bronchiseptica; Peritonitis; Peritoneal Dialysis, Continuous Ambulatory

INTRODUCTION

Bordella bronchiseptica is an obligate aerobic, nonfermentative gram negative coccobacillus that tests positive for motility, catalase, oxidase, urease, and nitrate reduction (1-5, 10). Although it is commonly found as either a commensal or a cause of respiratory tract disease in many wild and domestic animals, it has very rarely been implicated as a cause of infection in humans (1). A few cases of infections in animal caretakers, laboratory workers and immunocompromised patients have been reported (2-5, 14-18).

Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) is an important and lifesaving form of renal replacement therapy in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). However, peritonitis is a major complication that causes significant morbidity and mortality in ESRD patients with CAPD (6-9). Here, we report a case of relapsing CAPD peritonitis caused by B. bronchiseptica; the first case of a human infection in Korea.

CASE REPORT

A 56-yr-old male, treated with CAPD for ESRD secondary to gout for 13 yr, was admitted with complaints of a febrile sense and abdominal pain. The indwelling Tenckhoff catheter was cared for appropriately and there was no physical contact with animals. On admission, the temperature was 37.6℃ and the abdominal examination showed diffuse abdominal tenderness. The initial laboratory data included a hemoglobin of 10.6 g/dL, leucocytes 8,960/µL with 73.9% of neutrophils, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine (BUN/Cr) 42/10.2 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase/alanine transaminase (AST/ALT) 37/44 IU/L, total protein/albumin 5.7/3.3 g/dL, and C-reactive protein (CRP) 6.52 mg/dL. The peritoneal dialysate was turbid, and contained 5,100/µL leucocytes with 99% of neutrophils and gram-negative coccobacilli (Fig. 1). Culture of the peritoneal dialysate on sheep blood agar grew 0.5-1.0 mm sized flat, grey-white, non-hemolytic colonies after 24 hr of incubation at 35℃ and 5-10% CO2 (Fig. 2). The organism was a gram negative coccobacillus (Fig. 3), and also grew readily on MacConkey and salmonella-shigella agar. The organism tested positive for motility, catalase, oxidase, urease, and nitrate reduction, but did not ferment any carbohydrates. The isolated organism was finally identified as B. broanchiseptica (bionumber of GNI card: 000000130400000) by the Vitek II compact system (bioMeriux, Marcy-I'Etoile, France). The results of the susceptibility testing with an AST-N055 kit, from the Vitek II compact system (bioMeriux, Marcy-I'Etoile, France), showed resistance to minocyclin (>16 µg/mL) and trimethoprime/sulfamethoxazole (>80 µg/mL), but susceptibility to other antibiotics such as ticarcillin, piperacillin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime, aztreonam, imipenem, amikacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, and ciprofloxacin. Initially, according to our standard protocol, the patient was provisionally treated with intraperitoneal antibiotics, consisting of ceftazidime and ceftezole (each 1 g per 2-liter bag). The abdominal pain and turbid dialysate resolved within four days. The blood cultures obtained simultaneously prior to starting the antibiotics were negative. The nasal swab and culture were also negative. There was no evidence of an infectious source or animal contact. We continued the antibiotic therapy for two weeks, and the culture of peritoneal dialysate showed no growth at that time. After then, there were two episodes of relapsing peritonitis caused by the same organism. At first relapse, we considered the removal of the Tenckhoff catheter, the patient refused because there were no hemodialysis facilities in his residential area. The peritonitis was subsided after three days of treatment with intraperitoneal ceftazidime and amikacin. We kept the antibiotic therapy for three weeks, and the culture of peritoneal dialysate showed no growth. The following month, a peritonitis due to the same organism recurred one more time. With the consent of the patient, we removed the Tenckhoff catheter. The patient was treated with intravenous ceftazidime and amikacin for two weeks, and transferred to hemodialysis. He is doing well.

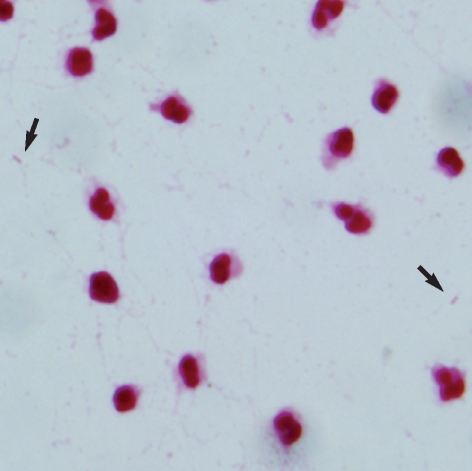

Fig. 1.

Gram-stained smear of peritoneal dialysate showing scattered gram-negative coccobacilli (arrows) among neutrophils.

Fig. 2.

Sheep blood agar plate showing 1-2 mm sized, raised, grayish-white colonies after 48 hr incubation at 37℃C, 5%-CO2.

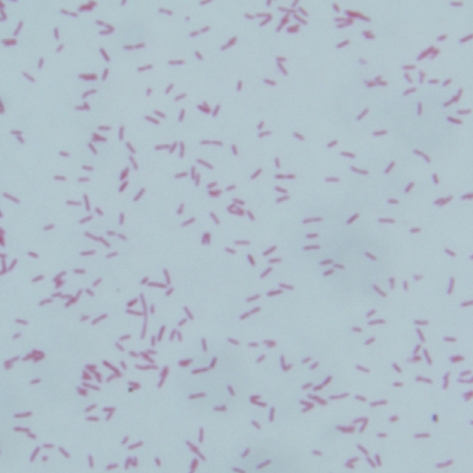

Fig. 3.

Gram-stained smear of colony on BAP after 48 hr incubation at 37℃C showing gram negative coccobacili.

DISCUSSION

B. bronchiseptica is known to cause respiratory tract infections in mammals. It has rarely been isolated from humans despite the considerable exposure of humans to animal sources of the microorganism (1, 3, 4, 11). It may occasionally be encountered as a commensal organism or as a colonizer of the human respiratory tract. It has rarely been identified as a pathogen in humans with underlying disease or immunocompromise (1-5, 12, 14-18). A history of exposure to animals may be significant but is not essential for B. bronchiseptica human infections (2, 19). In this case, the source of the infection was not found because there was no history of exposure to animals; the nasal swab and culture provided no additional information. However, the fact that the patient was an immunocompromised ESRD patient with CAPD, and had lived in an agricultural setting might have been risk factors for B. bronchiseptica infection.

B. bronchiseptica is an obligate aerobic, nonfermentative, gram negative coccobacillus that grows readily on simple nutritive media at 35℃. It is positive for catalase, oxidase, citrate utilization, motility, urease, nitrate reduction, tetrazolium reduction, and growth on salmonella-shigella agar, and it is negative for indole, acid production in oxidation-fermentation glucose and maltose media, tyrosine hydrolysis, and growth on tellurite agar (1-3, 5). B. bronchiseptica is distinguished from other fastidious Bordetella species, B. pertusis and B. parapertusis, by its easy growth on simple nutrient agar and its rapid urease positivity, as well as its ability to reduce nitrate to nitrite, and its motility (1). Motile, glucose-negative, nonfermentative bacilli are difficult to identify by the commonly used procedures in clinical laboratories (10). B. bronchiseptica can be confused with the Alcaligenes species, CDS group IVC-2 and group IVe, which have been reported to have different carbon substrate utilization patterns (3). The organism isolated from the peritoneal dialysate of our patient grew readily on BAP, MacConkey and SS agar at 35℃. It was identified as B. bronchiseptica by the Vitek II compact system (bioMeriux, Marcy-I'Etoile, France).

From recent in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility studies of B. bronchiseptica, the most effective agents for treatment appear to be aminoglycosides, antipseudomonal penicillins, broad-spectrum cephalosporins, tetracyclines and chloramphenicol (1, 20). However, several reports have emphasized a poor correlation between the in vitro antibiotic susceptibility of B. bronchiseptica and the clinical response (4). In our patient, the results of the susceptibility tests showed resistance only to minocyclin and trimethoprime/sulfamethoxazole, and susceptibility to all other antibiotics. The cause of the frequent relapses in our patient is unclear; the patient was treated with intraperitoneal antibiotics, initially consisting of ceftazidime and ceftezole, and with ceftazidime and amikacin after relapse. The testing showed that the B. bronchiseptica cultured from peritoneal dialysate was sensitive to these antibiotics. About the poor outcome of this patient, a question arises: What is the most appropriate treatment strategy? It is also possible B. bronchiseptica colonized the Tenckhoff catheter because two weeks of initial antibiotic therapy might have been inadequate to eradicate the organism completely. And, it may be necessary to consider catheter-related infection caused by colonization of this organism.

Peritonitis is a major and potentially serious complication of CAPD (6-9, 13). Recurrent episodes of peritonitis are associated with fibrosis of the peritoneal membrane, and eventually loss of the dialysis efficiency and failure of the technique (8). In 1981, Lawrence et al. first reported B. bronchiseptica peritonitis associated with CAPD (3). This is the first Korean report of a B. bronchiseptica human infection, associated with CAPD. Our experience suggests that B. bronchiseptica infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients in contact with domestic animals and/or immunocompromised patients. In addition, it may be necessary to consider early removal of Tenckhoff catheter in the case of CAPD peritonitis caused by this organism.

References

- 1.Woolfrey BF, Moody JA. Human infection associated with Bordetella bronchiseptica. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:243–255. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papasian CJ, Downs NJ, Talley RL, Romberger DJ, Hodges GR. Bordetella bronchiseptica bronchitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:575–577. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.3.575-577.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd LH, Anama L, Gutkin M, Chmel H. Bordetella bronchiseptica peritonitis associated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;14:232–233. doi: 10.1128/jcm.14.2.232-233.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amador C, Chiner E, Calpe JL, Ortiz de la Table V, Martinez C, Pasquau F. Pneumonia due to Bordetella bronchiseptica in a patient with AIDS. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:771–772. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.4.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh HK, Tranter J. Bordetella bronchicanis (bronchiseptica) infection in man: review and a case report. J Clin Pathol. 1979;32:546–548. doi: 10.1136/jcp.32.6.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenton P. Laboratory diagnosis of peritonitis in patients undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35:1181–1184. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.11.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin J, Rogers WA, Taylor HM, Everett FD, Prowant BF, Fruto LV, Nolph KD. Peritonitis during continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92:7–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-92-1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chew CG, Clarkson AR, Faull RJ. Relapsing CAPD peritonitis with rapid peritoneal sclerosis due to Haemophilus influenzae. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:821–822. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.4.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vargemezis V, Thodis E. Prevention and management of peritonitis and exit-site infection in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(Suppl 6):106–108. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.suppl_6.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickett MJ, Greenwood JR. Identification of oxidase-positive, glucose-negative, motile species of nonfermentative bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23:920–923. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.5.920-923.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns EH, Jr, Norman JM, Hatcher MD, Bemis DA. Fimbriae and determination of host species specificity of Bordetella bronchiseptica. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1838–1844. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1838-1844.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Blay K, Gueirard P, Guiso N, Chaby R. Antigenic polymorphism of the lipopolysaccharides from human and animal isolates of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Microbiology. 1997;143:1433–1441. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-4-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gokal R, Ramos JM, Francis DM, Ferner RE, Goodship TH, Proud G, Bint AJ, Ward MK, Kerr DN. Peritonitis in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis laboratory and clinical studies. Lancet. 1982;2:1388–1391. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91282-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buggy BP, Brosius FC, 3rd, Bogin RM, Koller CA, Schaberg DR. Bordetella bronchiseptica pneumonia in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. South Med J. 1987;80:1187–1189. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198708090-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoll DB, Murphey SA, Ballas SK. Bordetella bronchiseptica infection in stage IV Hodgkin's disease. Postgrad Med J. 1981;57:723–724. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.57.673.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meis JF, van Griethuijsen AJ, Muytjens HL. Bordetella bronchiseptica bronchitis in an immunosuppressed patient. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:366–367. doi: 10.1007/BF01973748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mesnard R, Guiso N, Michelet C, Sire JM, Pouedras P, Donnio PY, Avril JL. Isolation of Bordetella bronchiseptica from a patient with AIDS. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:304–306. doi: 10.1007/BF01967267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauwens JE, Spach DH, Schacker TW, Mustafa MM, Bowden RA. Bordetella bronchiseptica pneumonia and bacteremia following bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2474–2475. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2474-2475.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gueirard P, Weber C, Le Coustumier A, Guiso N. Human Bordetella bronchiseptica infection related to contact with infected animals: persistence of bacteria in host. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2002–2006. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2002-2006.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mortensen JE, Brumbach A, Shryock TR. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Bordetella avium and Bordetella bronchiseptica isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:771–772. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]