Abstract

Palmitoylated proteins have been implicated in several disease states including Huntington’s, cardiovascular, T-cell mediated immune diseases, and cancer. To proceed with drug discovery efforts in this area, it is necessary to: identify the target enzymes, establish efficient assays for palmitoylation, and conduct high-throughput screening to identify inhibitors. The primary objectives of this review are to examine the types of assays used to study protein palmitoylation and to discuss the known inhibitors of palmitoylation. Six main palmitoylation assays are currently in use. Four assays, radiolabeled palmitate incorporation, fatty acyl exchange chemistry, MALDI-TOF MS and azido-fatty acid labeling are useful in the identification of palmitoylated proteins and palmitoyl acyltransferase (PAT) enzymes. Two other methods, the in vitro palmitoylation (IVP) assay and a cell-based peptide palmitoylation assay, are useful in the identification of PAT enzymes and are more amenable to screening for inhibitors of palmitoylation. To date, two general types of palmitoylation inhibitors have been identified. Lipid-based palmitoylation inhibitors broadly inhibit the palmitoylation of proteins; however, the mechanism of action of these compounds is unknown, and each also has effects on fatty acid biosynthesis. Conversely, several non-lipid palmitoylation inhibitors have been shown to selectively inhibit the palmitoylation of different PAT recognition motifs. The selective nature of these compounds suggests that they may act as protein substrate competitors, and may produce fewer non-specific effects. Therefore, these molecules may serve as lead compounds for the further development of selective inhibitors of palmitoylation, which may lead to new therapeutics for cancer and other diseases.

Keywords: Palmitoyl acyltransferase, inhibitor, 2-bromopalmitate, cerulenin, tunicamycin

Introduction

Palmitoylation serves a number of important biological roles and affects the localization and activity of many signaling proteins. Since palmitoylation is necessary for the proper localization and activity of these proteins, many of which are integral to the development of human disease states, the process of palmitoylation is itself involved in multiple diseases such as Huntington’s Disease, various cardiovascular and T-cell mediated immune disorders, as well as cancer. For example, it has been demonstrated that preventing the palmitoylation of the mutant huntingtin protein causes an elevation in neuronal toxicity [1], suggesting a preventative role for palmitoylation in Huntington’s Disease. Palmitoylation may also play a role in the prevention of multiple cardiovascular diseases by affecting the localization [2] and activity [3] of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), the knockout of which has been demonstrated to cause hypertension and elevated artherosclerosis in vivo (reviewed in [4,5]). In addition, palmitoylation is likely involved in T-cell mediated immune diseases, such as Type-I diabetes, since T-cell-receptor (TCR) activation is predicated on the palmitoylation of TCR-associated proteins such as Lck [6], while it is also involved in cancer as palmitoylation is necessary for the proper activity of oncoproteins such as H-Ras [7] and Hck [8]. It appears that elevating the palmitoylation of certain proteins could be therapeutically beneficial. For example, since neuronal toxicity is associated with nonpalmitoylated forms of the huntingtin protein, enhanced lipidation of the mutant huntingtin proteins could provide positive results in the treatment of Huntingtin’s disease. Similarly, increased palmitoylation of eNOS would be expected to maintain its activity resulting in vasodilation and reduction in hypertension. In contrast, inhibition of palmitoylation may be beneficial in the treatment of autoimmune disorders and cancer by preventing the proper localization and activity of proteins such as Lck and H-Ras, which are involved in T-cell activation and cellular transformation, respectively. Due to the importance of palmitoylation, the proteins that catalyze these reactions are interesting novel targets for the development of treatments for a variety of diseases and disorders.

However, the enzymes responsible for protein palmitoylation, palmitoyl acyltransferases (PATs), have only recently begun to be elucidated. These enzymes have historically been difficult to identify because the classical biochemical approaches of purification and characterization have been unable to definitively identify these proteins. This difficulty is largely brought about by the nature of the proteins. As integral membrane proteins, attempts to express and isolate putative mammalian PATs in bacterial and yeast cells have met with limited success [9], and when isolated from mammalian cells there is a rapid loss of enzymatic activity. However, advancements have been made in the last several years that have allowed the identification of palmitoylated proteins as well as the PAT enzymes themselves. The first verifiable PAT enzymes were identified in Saccharomyces cervisiae in 2002. In these studies, the yeast proteins Erf2/Erf4 and Akr1p were identified as PATs specific for Ras2 [10] and casein kinase2 [11], respectively. These two enzymes share a conserved Asp-His-His-Cys (DHHC) sequence located within a cysteine-rich domain (CRD), that has been demonstrated to be the catalytic PAT domain of these enzymes [10,11]. It has subsequently been determined that 22 DHHC-CRD-containing proteins are present in humans [12]. Some of these proteins have been characterized with substrate-specific PAT activity [9,13,14]; however, detailed characterization of these proteins remains to be accomplished. Therefore, the development and use of palmitoylation assays that assist in the identification of PAT enzymes with substrate specificity is of particular importance. This is an essential step in the process of identifying selective inhibitors of PAT activity, which ideally, would selectively target particular PAT enzymes and so may have a lower incidence of non-specific side-effects.

Thus, in this review, two topics associated with protein palmitoylation will be discussed. First, the types of assays employed to identify palmitoylated proteins, PAT enzymes, and PAT inhibitors will be introduced, and the advantages and disadvantages of each will be discussed. Second, the currently known inhibitors of palmitoylation will be presented, and issues relating to their mechanisms of action and specificities will be discussed.

Palmitoylation assays

To proceed with drug discovery efforts in the area of protein palmitoylation, it is necessary to: establish efficient assays to study palmitoylation; identify the enzymes that catalyze these reactions; and conduct high-throughput screening to identify selective inhibitors of palmitoylation. Addtionally, an ideal palmitoylation assay would allow the identification of palmitoylated protein substrates. In this section, palmitoylation assays described in the literature will be discussed in these contexts.

Historically, the most frequently used protein palmitoylation assays have involved the metabolic labeling of cultured cells with radioactive forms of palmitate, such as [3H]palmitate [10,11,14–18] or 125I-IC16 palmitate [19,20]. Generally, cells are grown on culture plates and the labeled palmitate is added to the culture medium, taken up by the cells, and subsequently metabolically incorporated into the palmitoylation sites of proteins. The cells are then lysed, and the labeled proteins are purified and/or analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The radioactive emission signal is subsequently detected by fluorography when the dried gels are exposed to X-ray film. There are three advantages to using this method for the detection of palmitoylated proteins and PATs. First, palmitoylation can be monitored in live cells. Second, the palmitoylation of specific, full-length proteins can be determined. Third, rates of palmitoylation and depalmitoylation can be determined by performing pulse-chase analyses. However, there are also several disadvantages to using the radiolabeling techniques. First, investigators must take precautionary measures when working with radioactive materials. Second, this method requires long labeling and exposure times in order to obtain a sufficient signal for measurement. In general, cells are exposed to the radiolabeled palmitate for at least 4 h, and detection of palmitate incorporation into the protein can require days-to-months of exposure of the fluorogram. Lastly, the amount of radiolabeled palmitate incorporation and detection are dependent on multiple factors, such as the ability of the palmitate to enter cells, the ratio of labeled and unlabeled palmitate that is available within the cells, and the amount of palmitoylation that occurred prior to the labeling period [16]. Thus, this method cannot provide data pertaining to the stoichiometry of acylation. Because of the multiple handling steps and length of this procedure, this approach is unlikely to provide a feasible means for screening compound libraries for new palmitoylation inhibitors. Overall, this method is useful for the identification of palmitoylated proteins and PAT enzymes; however, it is not well-suitable for screening for inhibitors of palmitoylation.

Another method to study the palmitoylation of proteins involves the utilization of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) [15,16] in which proteins are resolved by chromatography, digested with a protease and identified by their peptide fingerprints. For the analysis of palmitoylated proteins, the lipid moiety is removed by treatment with hydroxylamine, which shifts the mass of the depalmitoylated peptide. Comparing the peptide masses with or without hydroxylamine treatment, allows the site of palmitoylation to be inferred [21]. An advantage of using MS is that it allows the estimation of the stoichiometry of the palmitoylation of a particular protein of interest. Also, this method of analysis provides the investigator with the exact mass of the modifying group, and allows the identification of novel palmitoylated proteins [15,22]. However, the disadvantages of using MS for the analysis of palmitoylation are that thioester-linked fatty acids are susceptible to alkali hydrolysis and can therefore be easily lost during sample preparation. In addition, palmitoylated peptides are extremely ‘sticky’, which also complicates their purification and analysis. Lastly, the time needed to carry out this procedure precludes it from being a feasible method for screening large compound libraries for novel inhibitors of palmitoylation.

An alternate method to study protein palmitoylation is fatty acyl exchange chemistry. In this method the fatty acid on the palmitoylation site is exchanged for a more readily detectable label [16]. In the first step of the process, all pre-existing free sulfhydryls are blocked by N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). Next, hydroxylamine is added to cleave the thioester bond that attaches the fatty acid to the cysteine at the site of palmitoylation, thus, removing the fatty acid group. This cleavage leaves the previously acylated cysteine residue with a free sulfhydryl group. In the third step, the newly created free sulfhydryl group is labeled with thiol-specific reagents such as [3H]NEM or non-radioactive biotin-conjugated 1-biotinamido-4-[4-(maleimidomethyl)c yclohexanecarboxamido] butane (Btn-BMCC). Once the palmitoylation site is labeled, the modified proteins can be analyzed by SDS-PAGE directly or following binding to streptavidin beads, and detected by either fluorography or chemiluminescence, depending on the label [16]. There are a number of advantages to using fatty acyl exchange to study protein palmitoylation. First, this method increases the sensitivity of detection compared to standard [3H]palmitate incorporation [16]. This allows the analysis of palmitoylated proteins that are expressed at relatively low levels that may not otherwise be detected. Second, since the hydroxylamine treatment removes virtually all of the palmitate from proteins, it provides a more accurate measurement of the stoichiometry of palmitoylation. Third, the method can employ non-radioactive labels. Fourth, this method is suitable to identify novel palmitoylated proteins. Lastly, since metabolic labeling is not required, analyses can be conducted with cell fractions or purified proteins. However, this method also has several limitations. For instance, it has the propensity to generate false positives due to the binding of thiol-specific reagents to the sulfhydryls of cysteines that were previously thioester-linked to moieties other than fatty acids. In addition, this method provides no information about the identity of the native group cleaved from the cysteine residue, and is too low-throughput to be of use in as a drug discovery assay. Overall, like radiolabeled palmitate incorporation, this method is useful for the analyses of palmitoylated proteins and PAT enzymes; however, it is not an efficient method to screen for inhibitors of palmitoylation.

Another method to study palmitoylation is by labeling the target proteins with ω-azido-fatty acids [23]. In this method, synthetic ω-azido-fatty acids, are added directly to live cells, where they incorporate into proteins at sites of S-palmitoylation or N-myristoylation in a fashion similar to [3H]palmitate or [3H]myristate, respectively, based on the length of the ω-azido-fatty acid. Following incorporation, the modified fatty acids are labeled with biotin, the proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE and identified by binding to streptavidin. The advantages of this method are that it is non-radioactive, it provides greater sensitivity in the detection of fatty-acylated proteins than does the use of radiolabeled fatty acids, it can be used to identify novel palmitoylated proteins, and the ability to biotinylate the target proteins provides an opportunities for enrichment of the fatty-acylated proteins. In addition, although this method is similar to radiolabeled palmitate incorporation from a procedural standpoint, it has the advantage of decreased autoradiogram exposure times, which makes this method more amenable to the identification of inhibitors of palmitoylation. However, the main disadvantages of this method are that the ω-azido-fatty acids are not commercially available and it is not rapid enough for screening large compound libraries for palmitoylation inhibitors. Overall, like radiolabeled palmitate incorporation, fatty acyl exchange chemistry and MALDI-TOF MS, this method is useful for the analyses of palmitoylated proteins and PAT enzymes; however, it is not an efficient method to screen large compound libraries for inhibitors of palmitoylation.

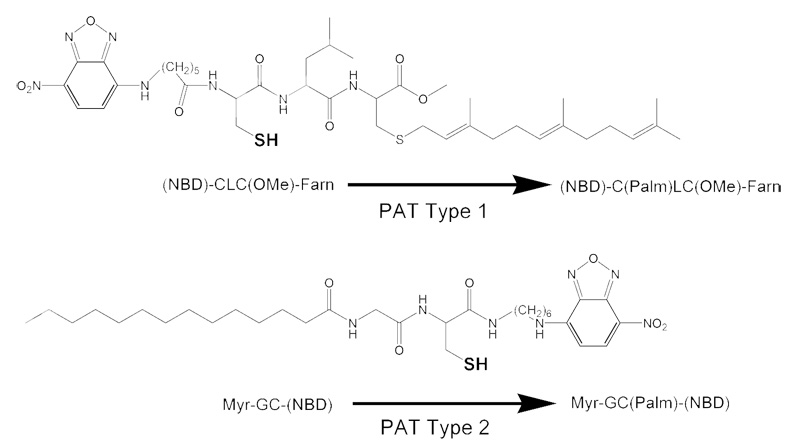

A further method to study palmitoylation is termed in vitro palmitoylation (IVP), which employs fluorescently-labeled lipopeptides (Figure 1) that mimic the specific palmitoylation motifs of C-terminally farnesylated and palmitoylated proteins, such as H, N and K2(A)-Ras, and N-terminally myristoylated and palmitoylated proteins, such as the Src-related tyrosine kinases. We have previously referred to PATs with these enzymatic activities as Type 1 and Type 2 PATs, respectively.

Figure 1.

Lipidated peptides used in IVP and cellular assays.

In the IVP method, samples containing the enzyme source are mixed with the fluorescently labeled lipopeptides for 8 min and the reaction is subsequently initiated by the addition of unlabeled palmitoyl-CoA. The PAT enzyme(s) under study catalyze the addition of the palmitoyl group to the cysteine residues on the lipopeptides over a period of 7.5 min. This modification causes a shift in the hydrophobicity of the peptide, which can be easily detected by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Therefore, one of the main advantages of this method is that the palmitoylated and non-palmitoylated forms of the peptides are directly quantified. The use of the two lipidated peptide substrates allows independent measurement of Type 1 and Type 2 activity. Also, like the fatty acyl exchange method, an advantage of this method is that it does not require the use of radioactive materials. In addition, this assay is much faster than other palmitoylation assays, making it more amenable to screening for potential inhibitors of palmitoylation. The main disadvantage to this method is that it only demonstrates the activity of a PAT toward the putative PAT recognition motifs represented by the peptides. Thus, the specific proteins modified by a given PAT cannot be determined using this method. Overall, this method is useful for the identification of PAT enzymes and is more amenable to screening for inhibitors of palmitoylation than the previously covered methods; however, it cannot be used to determine the palmitoylation status of endogenous proteins or identify novel palmitoylated proteins.

The last method to study palmitoylation is a non-radioactive, fluorescent, cell-based assay [24]. This method employs the fluorescently labeled lipopeptides discussed in the previous paragraph; however, it is conducted in a different manner. Unlike the IVP assay, which isolates PAT enzyme-containing membrane fractions and subjects those enzymes to analysis using exogenous palmitoyl-CoA in an in vitro environment, the cell-based assay studies the palmitoylation of the peptides in the intact cell with endogenous palmitoyl-CoA. In this method, mammalian cells are incubated in serum-free cell culture media containing the peptide of interest for approximately 10 min at 37°C. The extracellular peptides are removed by washing with ice-cold PBS. Next, the cells are lysed with ice-cold 50% methanol and the peptides are extracted into dichloromethane, dried under N2, fractionated by HPLC and detected by their fluorescence. As discussed above, palmitoylation of these peptides increases their hydrophobicity, producing a quantifiable peak that is separate from that of the non-palmitoylated substrate peptide. There are several advantages to this method. First, like several of these assays, this method is non-radioactive. Second, since the palmitoylated and non-palmitoylated forms of the peptides are easily resolved and quantified; this method provides quantitative measures of Type 1 and Type 2 PAT activity. Third, since the peptides are fluorescently labeled and localize in a manner consistent with the palmitoylation status of endogenous proteins, this method can be modified to study the intracellular trafficking of the lipidated peptides. Lastly, this method is much faster than other palmitoylation assays. The peptide treatment, extraction and drying process can be accomplished in an afternoon, and the HPLC elution and detection can be run overnight. Thus, many samples can be run in under 24 h, compared to multiple days or weeks necessary to complete other assays. In addition, since the intracellular localization of these peptides has been demonstrated to be dependent on palmitoylation status [24], a localization-based cellular palmitoylation assay may be developed in a 384 well format utilizing the IN Cell Analyzer 1000 from General Electric, which would greatly increase the through-put of this method. Therefore, this method is more amenable to screening for small molecule inhibitors of palmitoylation, as well as the identification of new PAT enzymes. However, there are two main disadvantages with this method. First, this method does not allow the identification of endogenously palmitoylated proteins or novel sites of palmitoylation on previously identified proteins. Second, as with the IVP assay, it only demonstrates the activity of a PAT enzyme toward the C-terminal farnesylcysteine and N-terminal myristoylglycine PAT recognition motifs represented by the peptides. Thus, the specific proteins targeted by a given PAT cannot be determined by this method. Overall, this method is useful for the identification of PAT enzymes and appears to be the most efficient method to screen for inhibitors of palmitoylation; however, it cannot be used to determine the palmitoylation status of endogenous proteins. The above-described assays are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Summary of palmitoylation assays.

| Assay | Intact cells or isolated proteins | Advantages | Disadvantages | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic labeling | Intact cells | • | Can identify palmitoylated protein substrates and PAT enzymes |

• | Semiquantitative |

| • | Radioactive | ||||

| • | Palmitoylation rates can be determined | • | Not amenable to screening for PAT inhibitors |

||

| MALDI-TOF MS | Isolated proteins | • | Can identify palmitoylated protein substrates and PAT enzymes |

• | Not amenable to screening for PAT inhibitors |

| • | Stoichiometry can be determined | ||||

| Fatty acyl exchange | Isolated proteins | • | Can be non-radioactive | • | Semiquantitative |

| • | Can identify palmitoylated protein substrates and PAT enzymes |

• | Not amenable to screening for PAT inhibitors |

||

| ω-azido-fatty acid incorporation | Intact cells | • | Non-radioactive | • | Not amenable to screening for PAT inhibitors |

| • | Can identify palmitoylated protein substrates and PAT enzymes |

||||

| In vitro palmitoylation | Isolated proteins | • | Distinguishes Type 1 and Type 2 PAT activity | • | Not amenable to the identification of palmitoylated protein substrates |

| • | Non-radioactive | ||||

| • | Quantitative | ||||

| • | Amenable to PAT enzyme identification and screening for PAT inhibitors |

||||

| Cell-based peptide palmitoylation | Intact cells | • | Distinguishes Type 1 and Type 2 PAT activity |

• | Not amenable to the identification of palmitoylated protein substrates |

| • | Non-radioactive | ||||

| • | Quantitative | ||||

| • | Amenable to PAT enzyme identification and screening for PAT inhibitors |

||||

Palmitoyl acyltransferase inhibitors

The lipid modification of proteins has attracted increasing interest as potential therapeutic targets in recent years. This interest is based on the necessity of these lipid groups for the proper localization and activity of important intracellular signaling proteins. The majority of research in this area has focused on the Ras proteins, and in particular, on the process of post-translational farnesylation. This is partly due to the fact that farnesyltransferases have been cloned [25–27] and used to identify inhibitors through high-throughput screening [25,28]. In contrast, the identification of selective inhibitors of palmitoylation has been obstructed by difficulty in the identification of the PAT enzymes themselves, and the lack of assays suitable for the high-throughput screening of potential inhibitors. In view of recent advances in characterization of PAT enzymology, i.e. identification of putative PATs containing the DHHC motif, it is likely that genetic manipulation of individual DHHC-containing proteins either by overexpression or ablation with RNA interference technologies, will be used to confirm PAT identities and substrate specificities. This should be highly useful in selecting PATs for the development of pharmacologic inhibitors and their assessment in multiple disease etiologies. This section provides information on the currently known inhibitors of palmitoylation and a discussion of their proposed mechanisms of action.

There are two broad categories of palmitoylation inhibitors: lipid-based and non-lipid compounds. The lipid-based palmitoylation inhibitors include compounds such as 2-bromopalmitate (2BP), tunicamycin and cerulenin analogs (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lipid-based inhibitors of protein palmitoylation.

Although these compounds can be used to inhibit the palmitoylation of proteins, none are particularly selective agents. For example, the palmitate analog 2BP has been widely used [29], and its inhibitory effects on the palmitoylation of several proteins including the Src-related tyrosine kinases, Rho family kinases and H-Ras have been described [29–31]. Therefore, 2BP acts as a broad inhibitor of palmitate incorporation, but does not appear to selectively inhibit the palmitoylation of specific protein substrates. Inside the cell 2BP is converted to 2BP-CoA[15]; however, the mechanism by which it inhibits palmitoylation is unknown [15]. Possibilities include the binding of 2BP-CoA to a PAT thereby forming an inhibitor: enzyme complex. Alternately, 2BP may be transferred to the target protein, but the decreased hydrophobicity compared with palmitate may reduce binding of the protein to the lipid bilayer. Additionally, 2BP may alter lipid metabolism by reducing the levels of intracellular palmitoyl-CoA that are available for palmitoylation. In fact, this compound inhibits a number of enzymes involved in lipid metabolism including carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1, fatty acid CoA ligase and glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, as well as triacylglycerol biosynthesis [32, 33]. Therefore, it is important to note that although 2BP inhibits palmitoylation, the effects of 2BP treatment are not necessarily due to its effects on protein palmitoylation.

Another lipid-based palmitoylation inhibitor is the nucleoside antibiotic tunicamycin (Figure 2). This compound is primarily known for its ability to inhibit the N-linked glycosylation of proteins [34]; however, it has also been demonstrated to inhibit the palmitoylation of proteins such as GAP-43, the estrogen receptor variant α, certain Ca2+ channels, and the myelin proteolipid protein [35–38]. Like 2BP, the mechanism by which tunicamycin inhibits palmitoylation is unknown; although, it has been suggested that it functions by competing with palmitoyl-CoA for binding to PATs.

Cerulenin (2,3-epoxy-4-oxo7,10 dodecadienoylamide), another lipid-based inhibitor shown in Figure 2, has also been shown to inhibit palmitoylation of proteins [39], including the myelin proteolipid protein [36] and CD36 [40]. Like 2BP and tunicamycin, the mechanism by which cerulenin inhibits protein palmitoylation is unknown. It has been suggested that cerulenin acts by alkylating sulfhydryl groups, thereby forming chemical adducts on the cysteines of either the protein acceptor or the PAT and inhibiting the process of palmitoylation [36,41]. Like 2BP, cerulenin also has effects on cellular lipid metabolism. Most importantly, it has been demonstrated to be an inhibitor of various types of fatty acid synthetases, and it has been shown to prevent yeast-type fungal growth by inhibiting the biosynthesis of sterols and fatty acids [42–45]. In particular the compound binds to β-keto-acyl-ACP synthetase [46], thus inhibiting the biosynthesis of fatty acids. To improve the selectivity of cerulenin, a series of aliphatic and aromatic analogs were synthesized and tested for their effects on protein palmitoylation and fatty acid synthetase [39]. A compound designed to more closely mimic the structure of palmitate, Compound 7e, demonstrated the greatest extent of inhibition of protein palmitoylation but did not inhibit fatty acid synthetase activity [39]. While this was promising in the sense that it offered a more-targeted palmitoylation inhibitor, the high reactivity of the epoxycarboxamide moiety and the hydrophobicity of the compounds precluded their further development as potential therapeutic agents.

In addition to the lipid-based inhibitors of palmitoylation discussed in the previous paragraphs, several non-lipid inhibitors have also been recently identified by medium-throughput screening of a chemical library [47] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Non-lipid inhibitors of protein palmitoylation.

It was demonstrated that Compounds I through IV are selective inhibitors of Type 1 (farnesyl-peptide) palmitoylation, whereas Compound V is a selective inhibitor of Type 2 (myristoyl-peptide) palmitoylation [47]. These compounds have been shown to inhibit palmitoylation both quantitatively, through use of the IVP assay discussed previously, and in intact cells, by observing their ability to inhibit the localization of palmitoylated GFP variants to the plasma membrane in intact cells. In addition, these compounds have been demonstrated to abrogate signaling through the Raf/Mek signaling pathway and decrease human tumor cell proliferation in vitro. The in vivo antitumor activities of compounds I through IV were also characterized in this study, and it was observed that treatment of Balb/c mice bearing JC tumors with each of these compounds leads to a decrease in tumor growth as compared to vehicle-treated mice. Unlike the lipid-based palmitoylation inhibitors, whose mechanisms of action are not known, the selectivity of these compounds suggests a specific mechanism of action of these compounds. Since these compounds are selective for C-terminal farnesyl-directed or N-terminal myristoyl-directed palmitoylation, they likely do not act as palmitoyl-CoA competitors, but rather may target the protein binding site. This mechanism would make it unlikely that they would disrupt fatty acid biosynthesis or other palmitoyl-CoA-dependent reactions. In continuing studies of these PAT inhibitors, two series of compounds are being optimized and evaluated as potential anticancer agents (unpublished data).

Summary

Overall, palmitoylation is an important lipidation event that affects the activity of many proteins involved in multiple human diseases, and should be considered an important target for therapeutic intervention. However, the development of palmitoylation inhibitors and the identification of mammalian PATs have been impaired by the lack of efficient, high-throughput, palmitoylation assays. Multiple palmitoylation assays have been described, each with their own advantages and disadvantages. The more recently developed assays are higher-throughput than earlier assays, which in turn makes them more amenable to screening for PAT enzymes and their inhibitors. Currently, two groups of palmitoylation inhibitors have been identified: lipid-based and non-lipid inhibitors of protein palmitoylation. The lipid-based palmitoylation inhibitors include compounds such as 2BP, cerulenin and tunicamycin, and have been used to inhibit palmitoylation in vitro and in cells. However, the mechanism of action of these compounds is still unknown, they lack defined substrate specificity, and affect other aspects of cellular function including lipid metabolism. The recently described non-lipid inhibitors of palmitoylation include Compounds I through V shown in Figure 3. These compounds are differentially selective for two palmitoylation motifs and likely act as competitors of the protein substrates, which should decrease their non-specific effects. In addition, evidence suggests that these selective inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of cancer. Therefore, these molecules may serve as lead compounds in the further refinement and development of future selective PAT inhibitors.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Huang K, Yanai A, Kang R, Arstikaitis P, Singaraja RR, Metzler M, Mullard A, Haigh B, Gauthier-Campbell C, Gutekunst CA, Hayden MR, El-Husseini A. Huntingtin-interacting protein HIP14 is a palmitoyl transferase involved in palmitoylation and trafficking of multiple neuronal proteins. Neuron. 2004;44:977–986. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Cardena G, Oh P, Liu J, Schnitzer JE, Sessa WC. Targeting of nitric oxide synthase to endothelial cell caveolae via palmitoylation: implications for nitric oxide signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu L, Dudler T, Gelb MH. Purification of a protein palmitoyltransferase that acts on H-Ras protein and on a C-terminal N-Ras peptide. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23269–23276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawashima S, Yokoyama M. Dysfunction of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:998–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000125114.88079.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. Cardiovascular and renal control in NOS-deficient mouse models. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R628–R638. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00401.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosugi A, Hayashi F, Liddicoat DR, Yasuda K, Saitoh S, Hamaoka T. A pivotal role of cysteine 3 of Lck tyrosine kinase for localization to glycolipid-enriched micro-domains and T cell activation. Immunol Lett. 2001;76:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prior IA, Harding A, Yan J, Sluimer J, Parton RG, Hancock JF. GTP-dependent segregation of H-ras from lipid rafts is required for biological activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:368–375. doi: 10.1038/35070050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pecquet C, Nyga R, Penard-Lacronique V, Smithgall TE, Murakami H, Regnier A, Lassoued K, Gouilleux F. The Src tyrosine kinase Hck is required for Tel-Abl- but not for Tel-Jak2-induced cell transformation. Oncogene. 2007;26:1577–1585. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ducker CE, Stettler EM, French KJ, Upson JJ, Smith CD. Huntingtin interacting protein 14 is an oncogenic human protein: palmitoyl acyltransferase. Oncogene. 2004;23:9230–9237. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lobo S, Greentree WK, Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. Identification of a Ras palmitoyltransferase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41268–41273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth AF, Feng Y, Chen L, Davis NG. The yeast DHHC cysteine-rich domain protein Akr1p is a palmitoyl transferase. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:23–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohno Y, Kihara A, Sano T, Igarashi Y. Intracellular localization and tissue-specific distribution of human and yeast DHHC cysteine-rich domain-containing proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:474–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma C, Yang XH, Hemler ME. DHHC2 affects palmitoylation, stability, and functions of Tetraspanins CD9 and CD151. Mol Biol Cell. 2008 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swarthout JT, Lobo S, Farh L, Croke MR, Greentree WK, Deschenes RJ, Linder ME. DHHC9 and GCP16 constitute a human protein fatty acyltransferase with specificity for H- and N-Ras. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31141–31148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resh MD. Palmitoylation of ligands, receptors, and intracellular signaling molecules. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re14. doi: 10.1126/stke.3592006re14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drisdel RC, Alexander JK, Sayeed A, Green WN. Assays of protein palmitoylation. Methods. 2006;40:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez-Hernando C, Fukata M, Bernatchez PN, Fukata Y, Lin MI, Bredt DS, Sessa WC. Identification of Golgi-localized acyl transferases that palmitoylate and regulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:369–377. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukata M, Fukata Y, Adesnik H, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Identification of PSD-95 palmitoylating enzymes. Neuron. 2004;44:987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berthiaume L, Peseckis SM, Resh MD. Synthesis and use of iodo-fatty acid analogs. Methods Enzymol. 1995;250:454–466. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)50090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peseckis SM, Deichaite I, Resh MD. Iodinated fatty acids as probes for myristate processing and function. Incorporation into pp60v-src. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5107–5114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hensel J, Hintz M, Karas M, Linder D, Stahl B, Geyer R. Localization of the palmitoylation site in the trans-membrane protein p12E of Friend murine leukaemia virus. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232:373–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.373zz.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang X, Nazarian A, Erdjument-Bromage H, Bornmann W, Tempst P, Resh MD. Heterogeneous fatty acylation of Src family kinases with polyunsaturated fatty acids regulates raft localization and signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30987–30994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hang HC, Geutjes EJ, Grotenbreg G, Pollington AM, Bijlmakers MJ, Ploegh HL. Chemical probes for the rapid detection of Fatty-acylated proteins in Mammalian cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2744–2745. doi: 10.1021/ja0685001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Draper JM, Xia Z, Smith CD. Cellular palmitoylation and trafficking of lipidated peptides. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:1873–1884. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700179-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James GL, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Rawson TE, Somers TC, McDowell RS, Crowley CW, Lucas BK, Levinson AD, Marsters JC., Jr Benzodiazepine peptidomimetics: potent inhibitors of Ras farnesylation in animal cells. Science. 1993;260:1937–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.8316834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pompliano DL, Rands E, Schaber MD, Mosser SD, Anthony NJ, Gibbs JB. Steady-state kinetic mechanism of Ras farnesyl: protein transferase. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3800–3807. doi: 10.1021/bi00130a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen WJ, Andres DA, Goldstein JL, Russell DW, Brown MS. cDNA cloning and expression of the peptide-binding beta subunit of rat p21ras farnesyltransferase, the counterpart of yeast DPR1/RAM1. Cell. 1991;66:327–334. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohl NE, Mosser SD, deSolms SJ, Giuliani EA, Pompliano DL, Graham SL, Smith RL, Scolnick EM, Oliff A, Gibbs JB. Selective inhibition of ras-dependent transformation by a farnesyltransferase inhibitor. Science. 1993;260:1934–1937. doi: 10.1126/science.8316833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webb Y, Hermida-Matsumoto L, Resh MD. Inhibition of protein palmitoylation, raft localization, and T cell signaling by 2-bromopalmitate and polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:261–270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Yang Y, Hu Y, Dang D, Regezi J, Schmidt BL, Atakilit A, Chen B, Ellis D, Ramos DM. Alphavbeta6-Fyn signaling promotes oral cancer progression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41646–41653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chenette EJ, Abo A, Der CJ. Critical and distinct roles of amino- and carboxyl-terminal sequences in regulation of the biological activity of the Chp atypical Rho GTPase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13784–13792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chase JF, Tubbs PK. Specific inhibition of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation by 2-bromopalmitate and its coenzyme A and carnitine esters. Biochem J. 1972;129:55–65. doi: 10.1042/bj1290055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman RA, Rao P, Fogelsong RJ, Bardes ES. 2-Bromopalmitoyl-CoA and 2-bromopalmitate: promiscuous inhibitors of membrane-bound enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1125:203–209. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(92)90046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tkacz JS, Lampen O. Tunicamycin inhibition of polyisoprenyl N-acetylglucosaminyl pyrophosphate formation in calf-liver microsomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;65:248–257. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(75)80086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patterson SI, Skene JH. Inhibition of dynamic protein palmitoylation in intact cells with tunicamycin. Methods Enzymol. 1995;250:284–300. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)50079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeJesus G, Bizzozero OA. Effect of 2-fluoropalmitate, cerulenin and tunicamycin on the palmitoylation and intracellular translocation of myelin proteolipid protein. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:1669–1675. doi: 10.1023/a:1021643229028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurley JH, Cahill AL, Currie KP, Fox AP. The role of dynamic palmitoylation in Ca2+ channel inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9293–9298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160589697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L, Haynes MP, Bender JR. Plasma membrane localization and function of the estrogen receptor alpha variant (ER46) in human endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4807–4812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831079100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawrence DS, Zilfou JT, Smith CD. Structure-activity studies of cerulenin analogues as protein palmitoylation inhibitors. J Med Chem. 1999;42:4932–4941. doi: 10.1021/jm980591s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jochen AL, Hays J, Mick G. Inhibitory effects of cerulenin on protein palmitoylation and insulin internalization in rat adipocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1259:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Vos ML, Lawrence DS, Smith CD. Cellular pharmacology of cerulenin analogs that inhibit protein palmitoylation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62:985–995. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00739-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Omura S. The antibiotic cerulenin, a novel tool for biochemistry as an inhibitor of fatty acid synthesis. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:681–697. doi: 10.1128/br.40.3.681-697.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawaguchi A, Tomoda H, Okuda S, Awaya J, Omura S. Cerulenin resistance in a cerulenin-producing fungus. Isolation of cerulenin insensitive fatty acid synthetase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1979;197:30–35. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vance D, Goldberg I, Mitsuhashi O, Bloch K. Inhibition of fatty acid synthetases by the antibiotic cerulenin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;48:649–656. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90397-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nomura S, Horiuchi T, Hata T, Omura S. Inhibition of sterol and fatty acid biosyntheses by cerulenin in cell-free systems of yeast. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1972;25:365–368. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.25.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Price AC, Choi KH, Heath RJ, Li Z, White SW, Rock CO. Inhibition of beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases by thiolactomycin and cerulenin. Structure and mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6551–6559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ducker CE, Griffel LK, Smith RA, Keller SN, Zhuang Y, Xia Z, Diller JD, Smith CD. Discovery and characterization of inhibitors of human palmitoyl acyltransferases. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1647–1659. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]