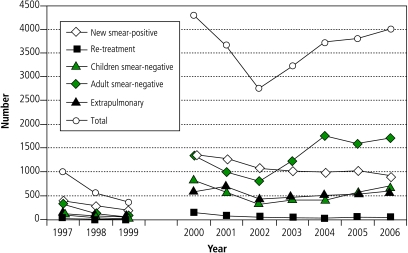

The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste was a Portuguese colony for 400 years, and was under Indonesian occupation for 25 years. After the population’s overwhelming vote for independence in August 1999, militia supported by the Indonesian military destroyed 70% of the country’s infrastructure; several thousand people were killed; and hundreds of thousands spent months as refugees in the mountains or outside the country. Following this unrest, the United Nations administered the country until independence in May 2002. Despite this complex emergency, the National Tuberculosis Programme (NTP) was established quickly and had one of the highest rates of new smear-positive tuberculosis (TB) in Asia (Fig. 1): the treatment success rate of over 80%1 has been discussed in two recent articles.2,3 In the base paper, Coninx describes factors that contribute to successful treatment. Several of these are found in the Timor-Leste experience, which also illustrates the challenges of moving from complex emergency to reconstruction and to routine TB control.

Fig. 1.

Reported tuberculosis cases in Timor-Leste 1997–1999 (Caritas TB Programme) and 2000–2006 (NTP)

By 1996, with financial and technical support from Caritas Norway, the Catholic Church in Timor-Leste had established a TB programme in its nationwide network of clinics. This ran parallel to the Indonesian NTP provided by health centres, which was seen to be weak due to irregular supplies and inadequate training and supervision of staff. The Caritas TB programme was based on the WHO DOTS strategy, a package of five elements aimed at achieving at least 70% detection and an 85% cure rate. A Timorese doctor and three or four regional supervisors provided intensive training to nurses, laboratory technicians and community volunteers. The Caritas programme operated in 11 of 13 districts, reporting almost 400 new smear-positive cases yearly (Fig. 1). Its strength was trust – as part of a church with strong popular support, and through links to the Timorese resistance movement.3 Its limitation was low coverage.

By 1999, almost all public health centres had been destroyed and minimal staff remained. However, most Catholic clinics were able to resume their TB work as soon as the population returned to the capital and, gradually, to their districts. After some initial reluctance the new United Nations administration appointed Caritas East Timor as the lead agency for the NTP. The main hindrance to restarting the programme was the delayed procurement of anti-TB drugs, but the NTP was already established and therefore could coordinate the many actors during the complex emergency. Each district had one international nongovernmental organization (NGO) responsible for health. Problems included donor competition, lack of institutional development and noncompliance with NTP guidelines.

In the reconstruction period, TB diagnosis, laboratories and treatment were transferred gradually to district health centres. The new district health teams included district TB coordinators, although the health reform did not favour disease-specific staff at this level. Ideally the NTP should have contributed to strengthening the general health services, but its impact was reduced because the central unit was outside the health ministry. As an NGO, Caritas East Timor also found it difficult to supervise governmental health institutions in the absence of central coordination with the health ministry.

The NTP central unit was part of Caritas East Timor (now Caritas Dili) until the end of 2005. Caritas Norway continued financial and technical support until this time, when support from the Global Drug Facility and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria became available. The transition was difficult and prolonged – only two out of five staff in the new central unit were recruited from the Caritas programme, although it provided support to train newly recruited health ministry staff.

Mountains limit access, so since 1996 the treatment regimen has been eight months (2RHZE/6EH) because directly observed treatment (DOT) is required only during the first two months with Rifampicin.4 Even so it has been difficult to ensure DOT in health centres, and health posts are not yet fully involved. In the capital, DOT was ensured through satellites staffed with church-based volunteers and providing temporary housing (albergues) for a few patients from remote areas in some districts. In a few districts church-based organizations identify TB suspects and provide DOT. Since 2004 Caritas Dili has supported community projects that include TB in one subdistrict in each district.

Following the transition from the Caritas programme to NTP, new smear-positive cases trebled. However, this was followed by a gradual decline even though case-finding and treatment were decentralized to subdistricts following a review in 2003 led by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (Fig. 1). Health centres’ performance could be improved by referring more sputum smears or TB suspects to the district health centres. Stigma and travel costs also may explain low case-finding. Many TB cases have no smear examination, mainly in the two main cities: Dili and Baucau. Although a doctors’ training course improved the situation in 2001–2002, the problem has increased due to the dependence on expatriate doctors who have a rapid turnover (Fig. 1). Since the 1990s, microscopy cross-checks have shown reasonable results overall.2

In spite of the emergency period, MDR-TB rates seem to be very low. In Australia a small and declining number of re-treatment failures have been confirmed to have MDR-TB (3 cases 2002–2004).5 A project approved by the Green Light Committee (see: http://www.stoptb.org/gdf/newsevents/archive/gdfglc.asp) is being set up for the treatment of up to 15 cases initially. Low numbers of MDR-TB cases could be explained by several factors: few TB drugs are available outside the NTP as the health ministry prohibited the sale of TB drugs in private pharmacies; a small private sector; and the eight-month regimen. HIV is apparently rare, but there is little testing.

In conclusion, the experience in Timor-Leste confirms that TB control can be implemented effectively during complex emergencies. The presence of a strong local NGO acting as lead agency can be a key factor in success. However, it is a challenge to ensure long-term strengthening of TB control in the country. ■

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing: WHO report 2006. Geneva: WHO;2006. (WHO/HTM/TB/2006.362)

- 2.Martins N, Heldal E, Sarmento J, Araujo RM, Rolandsen EB, Kelly PM. Tuberculosis control in conflict-affected East Timor, 1996-2004. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:975–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martins N, Kelly PM, Grace JA, Zwi AB. Reconstructing tuberculosis services after major conflict: experiences and lessons learned in East Timor. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rieder HL, Arnadottir T, Trebucq A, Enarson DA. Tuberculosis treatment: dangerous regimens? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly PM, Lumb R, Pinto A, da Costa G, Sarmento J, Bastian I. Analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from treatment failure patients living in East Timor. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:81–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]