Abstract

Motivation: Modification of proteins via phosphorylation is a primary mechanism for signal transduction in cells. Phosphorylation sites on proteins are determined in part through particular patterns, or motifs, present in the amino acid sequence.

Results: We describe an algorithm that simultaneously discovers multiple motifs in a set of peptides that were phosphorylated by several different kinases. Such sets of peptides are routinely produced in proteomics experiments.Our motif-finding algorithm uses the principle of minimum description length to determine a mixture of sequence motifs that distinguish a foreground set of phosphopeptides from a background set of unphosphorylated peptides. We show that our algorithm outperforms existing motif-finding algorithms on synthetic datasets consisting of mixtures of known phosphorylation sites. We also derive a motif specificity score that quantifies whether or not the phosphoproteins containing an instance of a motif have a significant number of known interactions. Application of our motif-finding algorithm to recently published human and mouse proteomic studies recovers several known phosphorylation motifs and reveals a number of novel motifs that are enriched for interactions with a particular kinase or phosphatase. Our tools provide a new approach for uncovering the sequence specificities of uncharacterized kinases or phosphatases.

Availability: Software is available at http:/cs.brown.edu/people/braphael/software.html.

Contact: aritz@cs.brown.edu; braphael@cs.brown.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Modification of proteins via phosphorylation is a primary mechanism for signal transduction in cells. Members of signaling pathways include kinases that phosphorylate proteins at tyrosine, serine or threonine residues and phosphatases that desphosphorylate proteins. Both kinases and phosphatases recognize their substrates in part through patterns, or motifs, present near the phosphorylation site in the amino acid sequence of the substrate. A number of such motifs have been identified and are recorded in databases, such as PhosphoSite Plus (www.phosphosite.org), Scansite (Obenauer et al., 2003), Mini-motif Miner (Balla et al., 2006) and PhosphoMotif Finder (Amanchy et al., 2007). However, many phosphorylation sites are not associated with a kinase and/or phosphatase. For example, over 54% of the 11 176 documented phosphorylation modifications in the Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD) (Peri et al., 2003) have no known upstream enzyme. Part of the reason for this knowledge gap is that discovery of phosphorylation sites is presently more efficient than identification of the kinase that phosphorylates the site. Traditional experimental methods that measure kinase–substrate interaction (such as co-immunoprecipitation or fluorescence resonance energy transfer) require some hypothesis as to the kinase involved in the phosphorylation. Computational methods to predict kinase–substrate interactions from structural information (Brinkworth et al., 2003) or from other known kinase substrates (Blom et al., 2004) have also been introduced, but such additional information is not always available.

Recently, algorithms have emerged to accurately predict substrates of some well-characterized kinases. NetworKIN (Linding et al., 2007) integrates phosphorylation motifs and protein interaction networks, relying on well-characterized kinase motifs from NetPhosK (Blom et al., 2004) and Scansite (Obenauer et al., 2003). NetPhorest (Miller et al., 2008), classifies the upstream enzymes of phosphorylation sites using 125 different sequence-based classifiers, and NetworKIN now integrates these classifiers. For algorithms such as these, knowledge of motifs for additional kinases and phosphatases would be useful.

A growing source of phosphorylation sites is phosphoproteomic experiments that simultaneously measure hundreds to thousands of phosphorylated residues in a cell (Cao et al., 2007; Olsen et al., 2006; Rush et al., 2005; Wolf-Yadlin et al., 2006). In a phosphoproteomics experiment, peptides containing a phosphorylated residue are identified from a purified sample via mass spectrometry (Hoffert and Knepper, 2007).The resulting phosphopeptides measured under the same experimental condition provide data for the identification of sequence motifs that indicate an interaction with a specific kinase or phosphatase that was active during the experiment.

The motif-finding problem arising from phosphoproteomics data is the following. Given a collection of peptides each containing a specific phosphorylated residue (serine, threonine or tyrosine), find a set of repeated patterns, or motifs, that are overrepresented in the phosphorylated peptides relative to a background set of unphosphorylated peptides. Note that all phosphorylated peptides share the phosphorylated residue, and thus the peptides can be aligned on the phosphorylated residue. This problem differs from many of the standard motif-finding problems in that the data is a mixture of motifs, representing the numerous kinase–substrate interactions that were measured in the experiment. Most motif-finding programs are optimized to solve a different problem, that of identifying and ranking relatively short motifs in a collection of long, unaligned background sequence, a problem motivated by the discovery of transcription factor binding sites (e.g. see Bailey and Elkan, 1994, 1995; Brazma et al., 1996; Buhler and Tompa, 2002; Jonassen et al., 1995; Lawrence et al., 1993; Rigoutsos and Floratos, 1998; Tompa et al., 2005). While these methods might output multiple motifs, usually in the form of a ranked list, these lists often contain variations of the same motif, and do not explicitly identify a mixture. A method called Motif-X (Schwartz and Gygi, 2005) was introduced for motif identification in aligned phosphoproteomics data and has since been employed in several studies, such as Xue et al. (2006). However, the type of motifs produced by Motif-X, patterns consisting of either a single letter at each position or a ‘wild-card’ character matching any position, are quite restrictive. Moreover, the greedy iterative approach used by Motif-X limits the motif mixtures that will be found. Finally Motif-X ignores the possibility of overlapping motifs.

We present the Motif Description Length (MoDL) algorithm for the discovery of mixtures of protein phosphorylation motifs. MoDL is based on the principle of minimum description length (MDL) (Grünwald, 2007) from information theory, and produces a set of motifs that succinctly describes the biases in sequence composition in a foreground set of phosphorylated peptides in comparison to a background set of unphosphorylated peptides. MoDL compares favorably to other published motif-finding programs including the aforementioned Motif-X, Teiresias (Rigoutsos and Floratos, 1998), MDL-Pratt (Brazma et al., 1996; Jonassen et al., 1995), MEME (Bailey and Elkan, 1994, 1995) and Gibbs Motif Sampler (Lawrence et al., 1993).

We also derive a motif specificity score (MSS) that measures whether or not the phosphopeptides containing a motif instance have a significant number of interactions with a specific kinase or phosphatase recorded in a protein–protein interaction database. A kinase/phosphatase-motif pair with a high MSS identifies a potential upstream kinase/phosphatase that targets the substrate motif. We apply our MoDL algorithm to several phosphoproteomic datasets and identify both known and novel phosphorylation motifs. Some of these motifs have high MSSs, implying that the motif describes the preference of a kinase or phosphatase to phosphorylate particular amino acid peptides.Application of MoDL and the MSS to large-scale phosphoproteomic datasets provides a new approach for uncovering the sequence specificities of uncharacterized kinases or phosphatases.

2 METHODS

Consider a collection of N phosphopeptides of fixed length aligned such that the common phosphorylated residue is in the center position. Additionally, consider a background matrix obtained from residue frequencies at each position in unphosphorylated peptides of the same fixed length with the same center residue. The goal is to describe the N phosphopeptides as a mixture of instances of an unknown number of motifs and sequences that contain no recognizable motifs.

Motif definitions fall into two major classes: pattern-based motifs that represent consensus sequences and profile-based motifs that represent the frequencies of each amino acid residue occurring at each position using position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs) (Stormo, 2000). We will use the former model in the motif discovery stage, and define a motif to be a pattern consisting of conserved positions that match any letter from a specified list (denoted by brackets ‘[]’) and wild-card positions (denoted by ‘.’) that match any letter.1 Each motif has a single phosphorylated residue, which we denote by an underlined character. Once motif instances are identified in a dataset we output a profile, or PSSM, constructed from these instances. Other pattern-based motif-finding algorithms, such as Motif-X (Schwartz and Gygi, 2005) and Multiprofiler (Keich and Pevzner, 2002) similarly convert the derived motifs into a scoring matrix. The use of patterns to represent motifs during discovery might appear to be disadvantaged compared with PSSMs, but in one comprehensive comparison of motif-finding algorithms for transcription factor binding site identification (Tompa et al., 2005), the best performing algorithm was a pattern-based method.

We use description length as a metric to evaluate how well a set of motifs describe a collection of phosphopeptides. Description length is an information-theoretic quantity that measures the amount of information (in terms of bits) required to represent (or encode) a dataset. To encode a collection of phosphopeptides, we must identify each residue in each phosphopeptide as originating from either an instance of a particular motif or as originating from the background (‘non-motif’) peptides. In addition, we must encode the motifs themselves. By finding the set of motifs with MDL, we annotate the peptides as motif instances in a way that maximizes the redundancy in the representation. MoDL aims to find such a motif set (Fig. 1A).

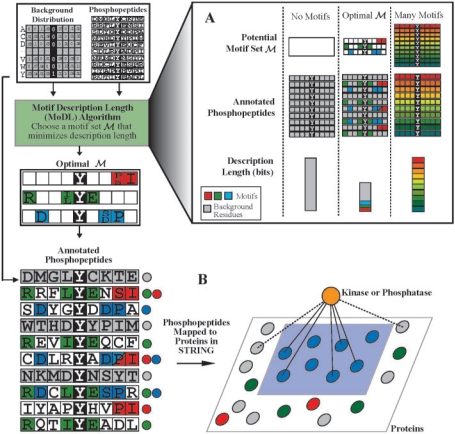

Fig. 1.

Overview of the MoDL algorithm and MSS calculation. MoDL uses the description length, a measure of the amount of information (bits) required to describe the input phosphopeptides using a motif set ℳ and the background distribution. MoDL attempts to find the optimal motif set with minimum description length. (A) With an empty motif set (i.e. no motifs), each peptide must be described explicitly from the background distribution, yielding high description length (left column). On the opposite extreme, each phosphopeptide can be described as a unique motif, but the resulting motif set yields high description length (right column). The optimal motif set includes only motifs that match several phosphopeptides, and minimizes the total description length required to represent both the motifs and the phosphopeptides (center column). After the optimal motif set is determined, the individual motifs are ranked according to the increase in description length when a motif is removed from the set. (B) Computing the MSS between a kinase and a motif group, the proteins containing a motif instance. The proteins are colored according to the motif instances they contain at one or more phosphorylation sites, and gray proteins contain no motif instances. To find the MSS for the blue motif D..Y.[SD]P, we consider all proteins in the motif group (blue). A kinase will have a high MSS if the number of interactions between the kinase and the motif group (solid lines) is significantly greater than the number of interactions between the kinase and proteins not in the motif group (dotted lines).

Let X be an N × L matrix containing the phosphopeptides of length (L + 1) with the known center phosphorylated residue removed. Let P be an 20×L matrix where 𝒫(i,j) gives the frequency of residue i in position j in a larger set of unphosphorylated peptides (also with the common center residue removed). For a motif set ℳ, let Λ(X,ℳ) denote the total number of bits required to encode both ℳ and X using ℳ. We first describe how to compute the description length for a particular set, ℳ, of motifs for a dataset X, and then describe a greedy approach to approximate the MDL.

2.1 Computing description length

Our aim is to find a set of motifs ℳ*={m1,…,mk} that minimizes the total number of bits required to encode both ℳ and X,

|

(1) |

Note that since P is independent of the choice of ℳ, we do not explicitly encode it.

The number of bits Λ(X,ℳ) required to encode X and ℳ is the sum of bits Λ(ℳ) required to encode the motif set and the number of bits Λ(X|ℳ) to encode the data described by the motif set. Computing Λ(ℳ) requires encoding the motif set ℳ={m1,…,mk}, which we do by concatenating the encodings of the individual motifs Λ(mi) preceded by an encoding of the value of k (assume some upper bound K≥k on the number of motifs). We assume that the peptides x1,…,xN are independent, and so the description length of X is the sum of the description length of each peptide.

|

(2) |

We will briefly describe how to compute Λ(mi) and Λ(xi|ℳ); see Supplementary Material for a detailed derivation. Each motif mi is encoded in three parts: (i) a vector that indicates whether each position is a conserved position or a wild-card position, (ii) the residues for each conserved position, described as either a list of indices (the list method) or as a 20-length binary vector (the vector method) and (iii) a vector specifying the encoding method used for each conserved position. The encoding method that requires the smallest number of bits is used for each conserved position.

To compute Λ(xi|ℳ), we first use the background frequency matrix P to encode residues that are not part of a motif instance. Let 𝒫(xij,j) be the background frequency of residue xij at position j in peptide xi. It has been shown that for a probability distribution over a set of characters (in our case, xijs), there exists a prefix code such that the description length of xij is [−log2𝒫(xij,j)] bits (Grünwald, 2007). We construct an N×L matrix B=[b1,…,bN]T, where bij=−log2𝒫(xij,j). Quantities that are common to all sets of motifs, such as B and P, are not encoded.

To compute Λ(xi|ℳ), peptide xi is encoded in three parts: (i) a vector specifying the motif instances that xi contains (or ‘0’ if it contains no motif instances), (ii) the background residues that are not part of any motif (encoded using bi) and (iii) the conserved positions (encoded using the motif instances that xi contains). It is possible for multiple motifs to represent a single conserved position if a peptide xi contains more than one motif instance. We choose the motif that requires the least number of bits to represent each conserved position.

2.2 The MoDL algorithm

Finding the motif set ℳ* with MDL is complicated by the fact that the space of motif sets is very large: the number of motifs is exponential in the alphabet size 20 and the peptide width L. Considering motifs that only appear in the data reduces the search space, but the number is still too large to directly compute. The MoDL algorithm builds a motif set ℳ from an initial set of simple candidate motifs using a greedy iterative approach. Candidate motifs are single-letter motifs (motifs with only one residue in one conserved position) that appear in the phosphopeptides. The empty motif set is initialized to ℳ(0)={} at time t=0. At iteration (t+1), we construct a set W of potential motif sets from the motif set ℳ(t) by removing a motif from ℳ(t), adding a motif to ℳ(t) or merging two motifs in ℳ(t). Merging two motifs mi and mj means taking the union of the list of residues for each conserved position t and updating the vector of conserved positions and the vector of encoding methods. We build W by performing the following five operations:

Remove: Remove a motif from ℳ(t).

Add: Add a candidate motif to ℳ(t).

Add/Remove: Add a candidate motif to ℳ(t) and remove another motif from ℳ(t).

Merge: Merge a candidate motif with a motif from ℳ(t).

Merge/Remove: Merge a candidate motif with a motif from ℳ(t) and remove another motif from ℳ(t).

The motif set ℳt+1∈W with the lowest description length is chosen. We repeat these steps for tmax=50 iterations, or until the description length has not decreased for l iterations (we set l=10). As a final step, we rank each motif by the increase in the description length when the motif is removed from the motif set ℳ.

The worst-case running time of each iteration is O(KR2), where K is the maximum number of motifs and R is the cardinality of the set of candidate motifs. Note that since P is constructed from the data X, the number of iterations l is the only user-defined parameter.

2.3 Computing the Motif Specificity Score (MSS)

A motif identified by MoDL suggests that there is a kinase or a phosphatase that prefers to bind to peptides containing an instance of the motif. We refer to the subset of phosphoproteins containing an instance of a motif as a motif group (proteins with multiple measured phosphopeptides are considered as one protein in the motif group). If we had lists of known substrates for each kinase and phosphatase, we would expect to find a kinase or phosphatase whose list of substrates overlapped considerably with a motif group. Since many kinase/substrate and phosphatase/substrate relations are unknown, we examined instead protein–protein interaction networks that have been derived through literature mining and high-throughput experiments (Mishra et al., 2006; von Mering et al., 2007).

Given a protein–protein interaction network, we define the MSS to quantify whether a kinase or phosphatase has more interactions with the motif group than expected by chance (Fig. 1B). A high MSS for a particular kinase or phosphatase indicates a binding preference for the subset of phosphopeptides containing instances of a particular motif. We define the MSS for a motif and a kinase/phosphatase as follows. Let N be the number of total proteins in the dataset, M be the number of proteins in the motif group and J be the number of interactions between the kinase and the N proteins. J is determined by an independent source and will be described later. Under the assumption that the subset of proteins that interact with the kinase/phosphatase are equally likely to be any subset, the probability of l or more interactions with the motif group is given by the hypergeometric cumulative distribution function:

|

(3) |

We define the MSS to be −log10(Pr[≥l interactions]). We report MSSs with a false discovery rate of 0.05 to compensate for multiple hypothesis testing.

In the experiments reported here, we compute the MSS by mapping each phosphopeptide to the corresponding protein in the STRING 7.1 database (von Mering et al., 2007), a compilation of experimentally measured and predicted (via literature mining and cross-species comparisons) protein–protein interactions (see Supplementary Material for more information). Note that STRING does not distinguish between multiple phosphorylation sites on the same protein, so there is no guarantee that an interaction in STRING corresponds to a particular phosphorylation site. In addition, since STRING records any associations between proteins and not only physical interactions, every protein has an association with itself of maximum score 1, but the majority of these edges do not signify protein–protein interaction. In this way, STRING does not provide information about autophosphorylation, a common feature of signaling pathways. Despite these difficulties, however, we find that a number of kinase/phosphatase-motif pairs give statistically significant MSSs.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Benchmarking on synthetic data

We performed three experiments to compare MoDL's ability to extract multiple motifs with other well-known algorithms. In the first experiment, we planted instances of two motifs, H.G[EV][KN]PY.C..[CR]G and Y..P, into a set of background peptides and ran a number of motif-discovery algorithms, including Motif-X (Schwartz and Gygi, 2005), Teiresias (Rigoutsos and Floratos, 1998), MDL-Pratt (Brazma et al., 1996; Jonassen et al., 1995), the Gibbs Motif Sampler (Lawrence et al., 1993), and MEME (Bailey and Elkan, 1994, 1995). MoDL outperforms all other methods, returning a nearly perfect reconstruction of the planted motifs (see Supplementary Material). The closest competitors were MEME and the Gibbs Motif Sampler, two algorithms that use PSSMs and thus further comparison of MoDL to MEME was performed.

In the second experiment, we constructed a synthetic dataset consisting of 10 instances each of two simple motifs, D..YE and [IL]Y….PP. For each instance, the non-conserved positions were chosen uniformly according to the background distribution. We then added 0, 5, 10, 15 and 20 peptides chosen from the background distribution to the motif instances, yielding datasets consisting of 0%, 20%, 33%, 43% and 50% background peptides. For each of these five synthetic datasets, we compared MoDL's performance to MEME by evaluating the labelling of peptides produced by the motif-finding program to the true labelling. We used the metrics of precision, the fraction of pairs of peptides with the same motif label that are both instances of one planted motif, recall, the fraction of all pairs of peptides that are instances of the same planted motif that have the same motif label and F-score, the harmonic mean of precision and recall. (see Supplementary Material for the calculation of precision and recall). MoDL obtains a higher average F-score over these datasets with lower SD: MoDL (0.9200±0.0447) versus MEME (0.7496±0.1702). Further, MoDL's recall is 1.0 for all five datasets while MEME's average recall is 0.8467±0.1193. With 0% background sequences, MoDL's precision is 1.0 compared with MEME's precision of 0.8901 and even with 43% background sequences MoDL's precision is 0.8182 with recall equal to 1.0, while MEME's precision and recall are 0.3701 and 0.633, respectively.

In the third experiment, we compared the performance of MoDL, Motif-X, and MEME on datasets from Scansite (Obenauer et al., 2003), a collection of phosphorylation sites and PSSMs for a number of well-characterized kinases. We constructed 20 datasets from different combinations of six different Scansite tyrosine motifs ABL, EGFR, PLCγ, SRC, FYN and LCK (see Supplementary Table S2). For every combination of three Scansite motifs from these six, we built a dataset consisting of the top 25-scoring peptides for each motif and added 75 background peptides to construct datasets with 150 peptides. In 10 out of 20 datasets, MoDL gives both higher precision and recall than MEME (see Supplementary Table S2 for graphs). Moreover MoDL's average F-score for these datasets, 0.4547±0.0969, is better than either MEME's average F-score (0.3607±0.0664) or Motif-X's average F-score (0.3968±0.1287). Further, MoDL's average precision (0.4266±0.0972) and average recall (0.5224±0.1618) outperform MEME's (0.3440±0.1383 and 0.5157±0.1979, respectively).

We also conducted a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of MoDL's performance compared with MEME and Motif-X. To create a ROC curve, we ran MEME to identify PSSMs and then annotated motif instances in the dataset with varying the scoring threshold. We also plotted MoDL's true positive/false positive rate on the same graph (Fig. 2A). Note that in ROC terms, recall is the same as the true positive rate. In the second experiment with the five synthetic datasets, MoDL maintains high true positive rate and low false positive rates as more background sequences are included. MEME's performance is highly variable. MoDL has a lower false positive rate in four of the five datasets compared with MEME's default scoring threshold and, as noted above, MoDL has a higher true positive rate in all datasets. In the 0% background dataset, MoDL's false positive rate is 0 and the true positive rate is 1, while for MEME to achieve a false positive rate of 0 requires the true positive rate to drop to 0.551.

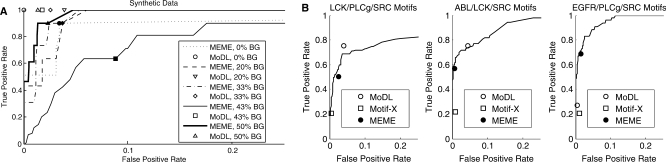

Fig. 2.

Performance of MoDL compared with MEME's ROC curves. Filled points on each curve represent the values returned with the default parameter settings of MEME (see Supplementary Material). (A) On a synthetic dataset with 10 instances each of D..YE and [IL]Y….PP, MoDL maintains constant true positive rate and only a slight decrease in false positive rate as the number of background (non-motif) sequences increases. In contrast, the performance of MEME varies drastically. (B) Representative examples comparing MoDL's performance to MEME and Motif-X on Scansite motifs. On the left, MoDL clearly outperforms both Motif-X and MEME. In the center, MoDL outperforms Motif-X and occupies a higher true positive rate on the MEME ROC curve than MEME's default settings. On the right, MEME outperforms both Motif-X and MoDL.

We ran a similar analysis on the 20 Scansite datasets from the third experiment. Figure 2 provides a few examples of MoDL's performance compared with the ROC curve determined by MEME's motifs (see Supplementary Figure S1 for all graphs). In the best ROC case shown in Figure 2, we obtain a true positive rate of 0.7550 and a false positive rate of 0.0410 compared with MEME's true positive rate of 0.5021 and false positive rate of 0.0628. Interestingly, in many cases the default settings for MEME showed poor true positive rates, which could be improved upon with a different scoring threshold than the default value (Supplementary Figure S1).

3.2 Motif discovery on experimental data

We applied MoDL to three phosphoproteomic datasets: human HER2 signaling (Wolf-Yadlin et al., 2006), mouse Mast Cell signaling (Cao et al., 2007) and various cancer cell lines (Rush et al., 2005). Each dataset consisted of peptides of length 13 with a measured phosphorylated tyrosine in the 7th position, and background sets were constructed from all 13mers with a tyrosine in the 7th position in the corresponding species proteome. The HER2 signaling dataset included (Wolf-Yadlin et al., 2006) two cell lines (parental ‘P’ and ‘24H’) that were stimulated separately with either epidermal growth factor (EGF) or Heregulin (HRG). See Supplementary Material for further details.

For each dataset, MoDL returned a ranking of one or two phosphorylation motifs (Table 1). We compared these motif sets to the motifs returned by Motif-X (Schwartz and Gygi, 2005), another program specifically designed to find phosphorylation motifs in aligned datasets. Briefly, Motif-X considers statistically significant residues in particular positions (called residue/position pairs) according to a binomially distributed model2. The algorithm is divided into a motif-building step and a data reduction step. In the motif-building step, statistically significant residue/position pairs are identified by a greedy recursive search. In the set reduction step, all peptides that contain an instance of the motif identified in the motif-building step are removed. These steps are repeated until the motif-building step fails to return a motif due to the lack of statistically significant residue/position pairs. The Motif-X score is the negative logarithm of the P-value for each motif. Note that Motif-X prunes the dataset after a motif is discovered by removing all peptides containing instances of a motif. Because of this pruning, the score of a motif found at a later iteration could be artificially low if some of its instances were removed earlier.

Table 1.

Motifs identified by each algorithm in each dataset

| Dataset | MoDL |

Motif-X |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motif-X | Compression | Motif-X | Compression | |||

| Motif set | score | (bits) | Motif set | score | (bits) | |

| HER2 P. EGF-stimulated | [DE]..Y | 31.65 | 122.92 | D..Y | 8.32 | 114.82 |

| 229 peptides | Y..[PV] | 20.74 | Y..P | 7.79 | ||

| HER2 P. HRG-stimulated | [DE]..Y | 30.18 | 100.80 | E..Y | 7.47 | 92.22 |

| 191 peptides | Y..[PV] | 18.78 | D..Y | 7.46 | ||

| HER2 24H. EGF-stimulated | [ADEN][ADLP].Y | 47.75 | 140.17 | D..Y | 8.83 | 89.40 |

| 225 peptides | Y..P | 18.92 | E..Y | 7.77 | ||

| HER2 24H. HRG-stimulated | [DENS][DNPRS].Y | 43.65 | 119.09 | D..Y | 8.22 | 77.36 |

| 209 peptides | Y..P | 16.08 | E..Y | 8.08 | ||

| Mast cell | [DE]..Y[ADESTY] | 64.75 | 137.69 | D..Y | 14.17 | 81.45 |

| 142 peptides | IY | 21.62 | YE | 9.45 | ||

| E..Y | 8.87 | |||||

| NPM-ALK | H.G[EV][KN]PY.C..[CR]G | 22.06 | 296.15 | Y..V | 16.0 | 178.53 |

| 248 peptides | E..Y | 7.50 | ||||

Motifs returned by MoDL are ranked by the increase in description length when the motif is removed from the motif set. The motifs returned by Motif-X are ranked by Motif-X score. The Motif-X score is the negative logarithm of the binomial P-value computed using the percentage of phosphopeptides with the motif and the percentage of background peptides with the motif. The compression for a motif set ℳ is the difference in description length Λ(X,{})−Λ(X,ℳ). See Supplementary Table S3 for a full table of all datasets.

In all datasets, MoDL returned higher scoring motifs according to Motif-X's score. For example, in the Mast cell dataset, the highest scoring motif found by MoDL, [DE]..Y[ADESTY], exceeds Motif-X's high-scoring motif D..Y by 50 orders of magnitude. We emphasize that MoDL does not explicitly optimize the Motif-X score.

The Motif-X score quantifies the significance of a single motif, while MoDL optimizes the expressiveness of a set of motifs. We therefore examined the compression of each motif set ℳ, defined as the difference Λ(X,{})−Λ(X,ℳ) in the number of bits required to encode the data with no motifs and the number of bits required to encode the data with ℳ. Not surprisingly, in all cases MoDL produced motif sets with larger compression than Motif-X. In some cases, such as the HER2 HRG datasets, the differences are quite large.

The NPM-ALK motif H.G[EV][KN]PY.C..[CR]G returned by MoDL has the largest number of conserved positions of all motifs discovered in the studied datasets. This motif corresponds to a linker peptide between zinc-finger domains (Jantz and Berg, 2004), and five zinc-finger proteins contain multiple instances of the motif: ZNF670, ZNF91, TIP20, ZNF24 and ZNF264. Additionally, instances of H.G[EV][KN]PY.C..[CR]G appear in 11 peptides from the five zinc-finger proteins that were not measured phosphorylation sites. While there is evidence of serine and threonine phosphorylation in the linker peptides (Jantz and Berg, 2004), our result indicates that tyrosine residues are also phosphorylated in the linker peptide. Schwartz and Gygi (2005) reported this example of tyrosine phosphorylation in the zinc finger linker as well. However, their reported consensus motif is the less specific E..Y, while MoDL recovers the entire linker consensus sequence.

3.3 Motif Validation on Experimental Data

For each motif returned by MoDL, we computed the MSS for kinases and phosphatases present in the underlying signaling networks to predict upstream enzymes that target the motif groups. See Supplementary Table S4 for the list of kinases and phosphatases tested.

Three of the motifs had significant MSSs in the HER2 datasets (Table 2). The motifs Y..P and Y..[PV] have high MSSs for ABL kinase, which is part of the known ABL consensus motif A.VIYAAP (Songyang and Cantley, 1995). In addition to the known interactions recorded in STRING, we predict that other proteins in the motif group are also substrates for ABL. In particular, GRF1 is one of the eight proteins in the Y..P motif group in the HER2 24H HRG dataset. There is no recorded interaction with ABL in STRING. However, the BCR-ABL fusion protein is known to phosphorylate GRF1 at the site Y1106 (Goss et al., 2006), the same site measured in the experiment. Another motif found by MoDL is [DENS] [DNPRS].Y which has a high MSS for PTPN11, a known phosphatase in the EGFR/HER2 pathway (Qu et al., 1999). PTPN11 has a high MSS in the HRG-stimulated condition, and PTPN11 is known to be activated with an increase in HRG (Vadlamudi et al., 2002). Finally, the motif [DENS] [DNPRS].Y has high MSS for SYK and ZAP70, two proteins in the same kinase family that have been implicated in breast cancer metastasis (Coopman et al., 2000).

Table 2.

MSSs for the motifs discovered in the HER2 datasets (false discovery rate = 0.05)

|

MSSs were computed for the proteins that appear in the STRING database. The motifs logos were created using WebLogo (Crooks et al., 2004). Motifs and interacting proteins for MEME are in Supplementary Table S5.

In the mast cell dataset, the highest scoring motif [DE]..Y[ADESTY] has a high MSS for LYN (1.7007). This MSS is significant with a false discovery rate of 0.15, 8 out of 11 proteins in the dataset that have interactions with LYN in STRING are in the motif group. Moreover, these 8 are known LYN substrates (FcIgERβ, FcIgERγ, SYK, BTK, DOK1 and a complex of SKAP55 and FYB/SLAP130) (von Mering et al., 2007). In addition, the motif [DE]..Y[ADESTY] resembles part of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM), a motif with consensus sequence [DE]…….[DE]..Y..[IL]…….Y..[IL] that is a known LYN target (Cao et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 1995). To compare our motif to the ITAM, we computed the MSS of the motif group determined by the partial ITAM [DE]..Y..[IL]. As expected, the partial ITAM has a high MSS for LYN (1.9626). The partial ITAM has a higher MSS because the resulting motif group is smaller than the motif group determined by [DE]..Y[ADESTY]; however, the partial ITAM motif is found in only half of the LYN targets (FcIgERβ, FcIgERγ, FYB and SKAP55) that were identified with the MoDL-derived motif [DE]..Y[ADESTY]. Interestingly, the partial ITAM has an even higher MSS (2.5667) for FYN kinase, suggesting that the [IL] position in the motif might be more specific for FYN.

We also compared the performance of MoDL and MEME on these datasets. On the HER2 P.EGF and HER2 24H HRG datasets MEME returned significant (false discovery rate ≤0.05) motifs for ABL. The MSS for ABL in these two datasets are 1.5453 and 1.4227, respectively, which are much lower than the corresponding MSS of 3.7628 and 3.4672 obtained by MoDL (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S5).

4 DISCUSSION

We introduced the MoDL algorithm for the discovery of protein phosphorylation motifs, and showed that MoDL outperforms other algorithms for identification of mixtures of motifs in phosphoproteomics datasets. In particular, MoDL outperforms Motif-X even when using Motif-X's scoring function, and generally produces motifs with higher specificity. Unlike other motif-finding methods, the MoDL algorithm requires no user-defined parameters besides criteria for termination. We showed that MoDL more accurately identifies motifs in synthetic datasets compared with both pattern-based motif-finding algorithms, such as Motif-X, Teriesias and MDL-Pratt, and profile-based algorithms, such as MEME. Note that our comparisons to other algorithms like MEME are not indictments of these methods, but more a reflection of the fact that many motif-finding algorithms are not optimized for the problem of separating a set of sequences into a mixture of instances of an unknown number of motifs. For example, MEME is optimized for the problem of finding motifs in unaligned sequences where motifs are expected to be relatively rare compared with the sequence length.

Many of the motifs identified by MoDL are short and do not have many conserved positions, both consistent with earlier studies (Schwartz and Gygi, 2005) and various motif databases (Amanchy et al., 2007; Balla et al., 2006; Obenauer et al., 2003). Our identification of the linker sequence in the zinc-finger proteins shows that longer and/or highly conserved motifs are identified by MoDL when they are present. The relatively small number of conserved positions in many of the phosphorylation motifs imply that de novo prediction of phosphorylation sites and/or substrates of a particular kinase/phosphatase from sequence motifs in proteins sequence alone will likely yield many false positives.

We introduced the MSS to evaluate whether a kinase or phosphatase preferentially interacts with proteins containing a given motif. While, the MSS is an imperfect measure of kinase/phosphatase enrichment because it depends on the quality of the underlying protein–protein interaction network, we were able to identify several kinase/phosphatase-substrate interactions in the HER2 datasets that are known to be active in this signaling pathway. We also obtain novel predictions of interactions that were not recorded in the STRING database including the phosphorylation of GRF1 by ABL. In contrast to the NetworKIN algorithm (Linding et al., 2007) – which links kinases to their substrates using STRING and well-characterized motifs in Scansite (Obenauer et al., 2003) – our approach focuses on using protein–protein interactions to validate newly discovered motifs identified in a proteomics experiment. We also used the MSS to directly compare motifs returned by MoDL and motifs returned by MEME on experimental data, suggesting further uses of this statistic for comparing motif-finding programs.

An important caveat to discovery of phosphorylation motifs in mass spectrometry datasets is that sample preparation steps used to enrich for phosphoproteins might introduce biases in the phosphorylation sites that are measured. The three datasets we reported used immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) and immunoaffinity purification (IAP), while other affinity-based methods like metal oxide affinity chromatography (MOAC) are becoming popular (see Hoffert and Knepper, 2007, for a review). A recent comparative study (Bodenmiller et al., 2007) found that ∼35% of the phosphopeptides were common to all three techniques, suggesting that the biases of each technique are not overwhelming.

Framing the motif-finding problem as one of minimizing description length is a promising approach, and further improvements to the MoDL algorithm are possible. In particular, we observed that MoDL returns at most three motifs in phosphopeptide data, and thus it is possible that MDL might be too restrictive of a measure in that two or more biologically distinguished motifs might be merged into a single motif. Notably, the motif [DE]..Y[ADESTY] in the mast cell dataset includes several distinct single-residue motifs for the SRC kinase family as listed in Schwartz and Gygi (2005). Thus, it might be useful to introduce a user-defined parameter of the number of motifs to return, allowing the user to incorporate prior knowledge about the number of interactions expected in a dataset. MoDL can also be modified to incorporate user-defined variable-length gaps as MDL-Pratt provides (Brazma et al., 1996). Finally, incorporating the MSS in the motif discovery stage will explicitly identify motifs with high MSSs in the protein–protein interaction network.

We demonstrate that the combination of sequence motifs identified in phosphoproteomics data from a single experimental condition with high-throughput protein interaction networks is a promising approach for linking kinases/phosphatases to their substrates in an experimentally stimulated signaling pathway.

Funding

Career Award at the Scientific Interface from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to B.J.R.); National Institutes of Health (grant 2P20RR015578 to A.R.S.); Beckman Young Investigator Award (to A.R.S.); NSF Graduate Fellowship (to A.R.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

1In most known protein phosphorylation motifs, there are few conserved positions. In contrast, many algorithms for transcription factor binding site identification assume that most positions are conserved.

2Motif-X filters the input dataset so that each peptide is unique (D. Schwartz, personal communication), and thus reduces the ability to find exact matches.

References

- Amanchy R, et al. A curated compendium of phosphorylation motifs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:285. doi: 10.1038/nbt0307-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Elkan C. The value of prior knowledge in discovering motifs with MEME. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 1995;3:21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla S, et al. Minimotif Miner: a tool for investigating protein function. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:175–177. doi: 10.1038/nmeth856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom N, et al. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics. 2004;4:1633–1649. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmiller B, et al. Reproducible isolation of distinct, overlapping segments of the phosphoproteome. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazma A, et al. Discovering patterns and subfamilies in biosequences. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 1996;4:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkworth RI, et al. Structural basis and prediction of substrate specificity in protein serine/threonine kinases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2003;100:74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0134224100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhler J, Tompa M Finding motifs using random projections. J. Comput. Biol. 2002;9:225–242. doi: 10.1089/10665270252935430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, et al. Quantitative time-resolved phosphoproteomic analysis of mast cell signaling. J. Immunol. 2007;179:5864–5876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coopman PJ, et al. The Syk tyrosine kinase suppresses malignant growth of human breast cancer cells. Nature. 2000;406:742–747. doi: 10.1038/35021086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks GE, et al. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss VL, et al. A common phosphotyrosine signature for the Bcr-Abl kinase. Blood. 2006;107:4888–4897. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünwald PD. The Minimum Description Length Principle. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffert JD, Knepper MA. Taking aim at shotgun phosphoproteomics. Anal. Biochem. 2007;375:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantz D, Berg JM. Reduction in DNA-binding affinity of Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins by linker phosphorylation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7589–7593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402191101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SA, et al. Phosphorylated immunoreceptor signaling motifs (ITAMs) exhibit unique abilities to bind and activate Lyn and Syk tyrosine kinases. J. Immunol. 1995;155:4596–4603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen I, et al. Finding flexible patterns in unaligned protein sequences. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1587–1595. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keich U, Pevzner PA. Finding motifs in the twilight zone. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1374–1381. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.10.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CE, et al. Detecting subtle sequence signals: a Gibbs sampling strategy for multiple alignment. Science. 1993;262:208–214. doi: 10.1126/science.8211139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linding R, et al. Systematic discovery of in vivo phosphorylation networks. Cell. 2007;129:1415–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ML, et al. Linear motif atlas for phosphorylation-dependent signaling. Sci. Signal. 2008;1 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1159433. ra2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra GR, et al. Human protein reference database-2006 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D411–D414. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obenauer JC, et al. Scansite 2.0: proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3635–3641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JV, et al. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peri S, et al. Development of human protein reference database as an initial platform for approaching systems biology in humans. Genome Res. 2003;13:2363. doi: 10.1101/gr.1680803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu CK, et al. Genetic evidence that Shp-2 tyrosine phosphatase is a signal enhancer of the epidermal growth factor receptor in mammals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:8528–8533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigoutsos I, Floratos A. Combinatorial pattern discovery in biological sequences: the TEIRESIAS algorithm. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:55–67. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush J, et al. Immunoaffinity profiling of tyrosine phosphorylation in cancer cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:94–101. doi: 10.1038/nbt1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Gygi SP. An iterative statistical approach to the identification of protein phosphorylation motifs from large-scale data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1391–1398. doi: 10.1038/nbt1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Cantley LC. Recognition and specificity in protein tyrosine kinase-mediated signalling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:470–475. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormo GD. DNA binding sites: representation and discovery. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:16–23. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa M, et al. Assessing computational tools for the discovery of transcription factor binding sites. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:137–144. doi: 10.1038/nbt1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi RK, et al. Differential regulation of components of the focal adhesion complex by heregulin: role of phosphatase SHP-2. J. Cell. Physiol. 2002;190:189–199. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mering C, et al. STRING 7–recent developments in the integration and prediction of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):358–362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf-Yadlin A, et al. Effects of HER2 overexpression on cell signaling networks governing proliferation and migration. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2:54. doi: 10.1038/msb4100094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, et al. SUMOsp: a web server for sumoylation site prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W254. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.