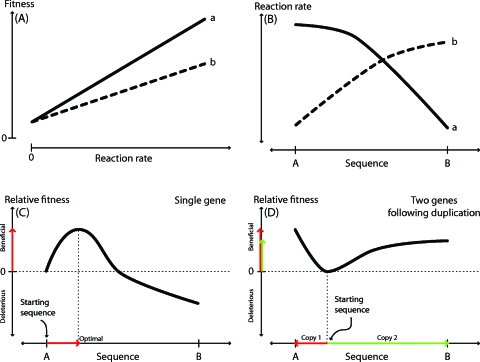

Figure 1. The example relationships between reaction rate, enzyme sequence, and organismal fitness.

(A) shows the relationship between reaction rate and fitness for two reactions a and b, where a is a larger determinant of fitness than b. (B) shows how reaction rates for a and b vary as the enzyme sequence moves between the sequences A and B. The reaction-rate–fitness and sequence–reaction-rate functions in the top two panels produce the single enzyme fitness landscape (C) for enzyme sequences between A and B. First, the optimal enzyme sequence is intermediate between specialists A and B, reflecting the trade-off between A and B. Consequently, an initial sequence of A will be pushed by natural selection toward this intermediate sequence with the accompanying gain in fitness (red arrows). Finally, panel (D) reflects the consequences of duplicating this enzyme and thus freeing evolution from the trade-off between reactions a and b and inducing an adaptive burst in both duplicates. One copy is free to specialize in reaction a (red arrows) while the second copy can specialize in b (green arrows). The total fitness is the sum of the two independent gains, indicating that duplication and specialization enables natural selection to produce an organism with overall higher fitness than is possible with a single enzyme sequence alone.