Abstract

This article describes a Sleep Education Program (SEP) designed to teach owner/operators and direct care staff working in adult family homes (AFHs) how to improve the sleep and nighttime behavior of older residents with dementia. There have been no sleep intervention studies conducted in adult family homes, and strategies that are known to improve sleep in community-dwelling older adults or nursing home residents may not be feasible or effective in AFHs because of their unique care environment. The SEP was developed based on experiences treating sleep disturbances in community-dwelling older adults with dementia (the Nighttime Insomnia Treatment and Education in Alzheimer's Disease [NITE-AD] study). In this paper, we address both the clinical and empirical challenges faced by researchers recruiting and intervening in adult family homes, raise issues pertinent to assessment of residents and staff, and discuss implications for evaluating the impact of behavioral treatments for sleep/wake disturbances in AFH residents.

Keywords: adult family homes, sleep, dementia, community residential care, board and care facilities, long-term care

Introduction

Sleep and nighttime behavioral disturbances such as wandering, getting out of bed repeatedly, and day/night confusion are widespread among residents with dementia in adult family homes (AFHs).1 Residents of adult family homes have higher rates of functional and health problems 2 that can contribute to sleep disturbances than do community-dwelling persons with dementia, and paid caregivers have demanding on-the-job responsibilities and schedules not typically faced by family caregivers. Identification of strategies that could be used as part of a staff educational program to manage sleep and nighttime behavioral disturbances in this unique environment is sorely needed. If successful, such strategies would help residents remain in a less restrictive environment for a longer time, and enhance resident quality of life. The purpose of this paper is to discuss both the clinical and empirical challenges faced by researchers to recruit and test interventions for improving sleep and lessening nighttime behavioral disturbances in persons living in adult family homes.

Characteristics of AFHs

The National Health Provider Inventory (NHPI) estimated there are more than 34,000 licensed board and care homes, serving the needs of over 600,000 persons, two-thirds of whom are elderly, and one-third of whom have moderate to severe cognitive impairment. 3 AFHs are at one end of the board and care facility continuum, being private residences that provide room and board, 24-hour supervision, and assistance with personal care tasks for 2 – 6 residents not related to the owner or operator. 4, 5 Larger facilities include adult residential care (ARC) facilities, which provide board and care for seven or more adults who need 24-hour assistance and oversight, and assisted living (AL) facilities, which provide independent living units with access to personalized care and support services on an as-needed basis. Adult family homes, which also go by names such as rest homes, adult foster homes, boarding homes, and personal care homes, fill a well-defined niche between assisted living and nursing homes, and have become a widely accepted alternative to nursing homes for the care of older adults with dementia. Many elderly persons who need residential care choose adult family homes over other options because of their small size and homelike environment.

Despite their small size, adult family homes provide care for adults who have a wide range of physical, cognitive, or mental health issues. In a recent study of 743 residents referred to AFH, ARC, or AL facilities affiliated with V.A. Medical Centers in four Western states (Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska), AFH residents had greater needs for assistance with activities of daily living than residents in either ARC or AL settings. 2 Studies have also shown that residents of AFHs tend to have higher levels of behavioral disturbances than either ARC or AL facilities. 6 Despite these increased care demands, AFHs are less likely to have registered nurses on staff (60% vs. 72% in ARCs and 100% in ALs). AFHs are also significantly more likely to be owned by non-native English speakers (67% vs. 5.3% for ARCs and 7.7% for ALs), 2 which, in some instances, can lead to communication challenges for AFH staff, residents, and family members who must work together when care-related problems such as nocturnal disturbances arise.

Sleep disturbances in AFHs

Wandering, particularly at night, has been identified as one of the most challenging resident behaviors for AFHs to manage. One study showed that 29% of residents were waking others up at night in the previous week. 5 In 2003, our research team completed a survey of 101 AFHs in three counties in Washington (King, Pierce, and Snohomish) asking about the occurrence of specific sleep or nighttime behavioral disturbances in their residents with dementia.1 Sixty-eight percent of the surveyed AFHs reported having one or more residents with some form of sleep or nighttime behavioral disturbance, including getting up during the night (83%; excluding 1-2 brief bathroom trips), nocturnal incontinence episodes (72%), waking too early in the morning (71%), talking, yelling, or calling out at night (62%), and wandering or pacing (60%). Eighty-five percent of the surveyed AFHs expressed interest in participating in a study that would teach care providers behavioral strategies for improving sleep problems in their residents.

However, little is known about how best to treat these problems. Board and care homes vary widely in their size, type of ownership, staffing schedules, physical environment, resident eligibility criteria, physician access, level of family involvement, state licensing requirements, and ratio of private/public pay clients. There have been no sleep intervention studies conducted in board and care homes, and strategies that have been shown to improve sleep in community-dwelling individuals or nursing home residents may not be feasible or effective in group home settings.

To address these needs, we developed a dementia-specific Sleep and Education Program (SEP) for reducing sleep and nighttime behavioral disturbances in one type of small residential care facility, the adult family home (AFH). The efficacy of the SEP program is currently being tested in a randomized controlled trial. The purpose of this article is to describe some of the challenges we have faced and the lessons learned about recruiting for research in adult family homes, assessing residents and staff, and implementing behavioral treatment programs in AFH settings. We also present a case study from the ongoing clinical trial to provide evidence for the potential utility of behavioral recommendations for reducing sleep disturbances in AFH residents with dementia.

The Seattle Protocols Sleep Education Program (SEP) for adult family homes

Given the prevalence of nocturnal behavioral disturbances in surveyed AFHs, we developed a Sleep Education Program for training staff to improve the sleep of AFH residents. The SEP was derived from the community-based NITE-AD (Nighttime Insomnia Treatment and Education in Alzheimer's Disease) study. 7 NITE-AD is a family caregiver-focused intervention designed to improve sleep and reduce nighttime behavioral disturbances in persons with dementia. NITE-AD is one of several Seattle Protocols 8 that draw upon social-learning and gerontological theories 9, 10 to teach caregivers how to alter their interactions with persons with dementia in order to reduce behavioral problems and enhance patient and caregiver quality of life.

Since sleep problems in dementia have physiological and circadian causes as well as behavioral and environmental triggers, 11, 12 the community NITE-AD study is a multi-modal in-home program that teaches caregivers to use a combination of sleep hygiene strategies, daily walking, and increased light exposure as well as behavioral problem-solving to reduce sleep problems in persons with Alzheimer's disease. After talking with representatives from AFH professional associations and conducting a small pilot study to evaluate feasibility and clinical care issues, we modified the NITE-AD community intervention to make it more suited for use in adult family homes.

For example, the original NITE-AD program placed participants on a daily walking program. 13 However, for AFHs with only one staff person on duty, it would be unsafe to take one resident for a walk if it meant leaving other residents unsupervised. Similarly, helping cognitively impaired individuals sit in front of a stationary light box at the same time every day requires dedicated staff time that is not feasible in most AFH settings. 14 In contrast, the SEP emphasizes the importance of increased daytime activity and ambient light exposure for improving nighttime sleep, but does so by helping staff problem-solve strategies for accomplishing these goals within the context of their unique home environment, staffing patterns, and overall resident care demands.

Table 1 shows the general content of the four weekly training sessions, which are conducted with the owner/operator and whatever staff are identified as key in developing and following through with a Sleep Education Plan. Staff are given information about good sleep practices, with an emphasis on specific environmental (reducing nighttime light and noise; increasing daytime ambient light), dietary (eliminating caffeine), and sleep scheduling (reducing afternoon/ evening napping; increasing daytime social and physical activity; consistent, appropriate bed and rising times) factors that have been shown to be associated with sleep disturbances in older adults with dementia. Staff caregivers also track bed and rising times on a daily log.

Table 1.

SEP treatment outline

| Session 1 | Introductions. Discuss causes of sleep problems in dementia. Identify potential sleep scheduling, daytime inactivity, dietary, environmental, or health causes for night awakenings. Develop behavioral sleep plan for the next week. |

| Session 2 | Review success with sleep plan. Describe overall A-B-C approach to behavioral change.15 Use ABCs to problem-solve any challenges that emerged in past week adhering to sleep plan. Set goals for upcoming week. |

| Session 3 | Review success with sleep plan and problem-solve challenges that emerged in past week. Develop individualized list of pleasant activities that can be implemented daily with resident in 15-minute increments at peak napping times during the afternoon and evening. |

| Session 4 | Follow-up on homework. Discuss sleep benefits observed by subjects since beginning treatment. Develop plan for continued adherence to behavioral program, and use of ABCs to deal with patient nocturnal disturbances. |

Characteristics of AFH Residents and Staff

Baseline assessments have been completed on 25 residents from 19 adult family homes into a 4-week randomized trial examining the use of SEP to improve sleep in residents with dementia, compared to a usual care control condition. Almost three-fourths of the AFHs (77%) in the SEP study to date have been owned by private individuals or families, and 26% had corporate ownership. Homes were caring for an average of 4.8 residents (range 1 – 6), who had an average of 3.6 health conditions in their resident record (range 1 – 9). Compared to participants enrolled in the original community-based NITE-AD study, 7 the AFH residents have been significantly older (t(59) = 5.20, p < .001), and tended to be more cognitively impaired (t(59) = 1.88, p = .06) (Table 2). The AFH residents also had higher rates of sleeping medication use than the community-dwelling subjects, although this difference is not significant (χ2(1, N = 61) = 1.91, p = .17).

Table 2.

Baseline descriptive data, NITE-AD community versus Adult Family Home samples

| Baseline Variable | NITE-AD Patients (n=36) | AFH Residents (n=25) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Age* | 77.7 (7.3) | 63 – 93 | 87.0 (6.2) | 76 – 101 |

| Education | 14.9 (3.0) | 8 – 20 | 14.5 (3.0) | 10 – 20 |

| Mini-Mental State | 11.8 (8.4) | 8 – 20 | 7.9 (7.3) | 0 – 23 |

| Examination Score | ||||

| Dementia duration (yrs) | 5.8 (3.4) | 1 – 15 | 6.5 (5.1) | 1 – 22 |

| % using sleep meds | 31% | 50% | ||

| Night time awake (hours) | 1.8 (1.4) | <1 – 5.9 | 2.8 (1.3) | <1 – 6.0 |

| (actigraphy)* | ||||

| Nighttime sleep % | 81.6 (11.6) | 53 – 99 | 75.0 (10.9) | 50 – 93 |

| (actigraphy)* | ||||

| Daytime inactivity (hours) | 1.4 (1.3) | <1 – 5.2 | 4.8 (2.5) | <1 – 8.3 |

| (actigraphy)* | ||||

| Gender (% female) | 44% | 45% | ||

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 92% | 100% | ||

p < .05 comparing community-based NITE-AD subjects vs. AFH residents

Based on wrist actigraphy data collected for a week prior to initiating treatment, the AFH residents spent more time awake at night (t(59) = 2.82, p = .01) (Table 2), and their daytime inactivity was almost four-fold that of the community-dwelling NITE-AD subjects (t(59) = 6.94, p < .001). These population and sleep disturbance differences were important for us to keep in mind since they could impact treatment delivery and efficacy of the behavioral intervention. For example, identification of pleasant, individualized activities that could engage residents and keep them awake during the day (c.f., Richards et al.16) is a particularly key component of the SEP intervention in the AFH setting where daytime inactivity is so predominant. Because of the high rates of sleeping medication use and medical morbidity, participating residents' physicians are informed about the SEP study, so any safety concerns can be incorporated into treatment recommendations and medication changes can be monitored.

To date, AFH staff caregivers in the SEP study have been significantly more likely to be female (95% vs. 72%, χ2(1, N = 61) = 5.64, p = .02), non-white (27% vs. 89% Caucasian, χ2(1, N = 61) = 23.7, p < .001), and younger (mean age 43.9 vs. 63.3 years, t(59) = 5.38, p < .001) than were family caregivers in the community-based NITE-AD sample. 7 Seventy-seven percent of AFH caregivers reported that they speak some language other than English at home. Unlike nursing homes, which by federal regulation are required to have a licensed nurse available at all times, 17 many adult family homes also often have no licensed health care professionals on staff, and direct care staff may have limited training in dementia care. 18 In the SEP study, only 5 staff caregivers (23%) have had an RN or LPN degree. Thus, treatment-related informational handouts, record-keeping forms, and behavioral treatment plans all needed to be simplified to be appropriate for use with both native and non-native English speakers, as well as for persons with a range of educational backgrounds and reading or literacy levels.

Challenges conducting an intervention study in adult family homes

A number of administrative and organizational factors unique to adult family homes have impacted recruitment and implementation of the ongoing SEP intervention study. Whereas skilled nursing or assisted living facilities typically assign staff to one of three day, evening, or nighttime shifts, adult family homes use a wide variety of facility staffing arrangements. For example, some direct care staff work standard 8-hour shifts under the supervision of an owner-operator who is only occasionally in the home; in other cases, direct care staff work round-the-clock shifts for several days then rotate off for several days and are replaced by other 24-hour rotating staff; in still other situations, the owner/operator may reside in the home with the residents, either as part of an extended-family care system or as the sole care provider 24 hours/day, 7 days/week year-round. In our ongoing AFH study, 24% (6/25) of participating caregivers work day shift, 20% (5/25) work night shift, 28% (7/25) live on an ongoing basis in the AFH residence, and the remainder work a combination or float across shifts.

Such variability in AFH work schedules presents a number of challenges for research recruitment, data collection, and treatment implementation. In terms of recruitment, just making contact with someone who has authority over the AFH household can be difficult. In our investigation, we initially send letters describing the research study addressed to the owner/operator of the AFH as a point of contact; however, these letters may not be seen by the intended recipient right away if s/he is not living on-site. We follow up the letters with phone calls to the AFH, which may not be answered if staff are busy with other responsibilities caring for residents. Messages left may not be returned since recruitment calls may be perceived as a kind of solicitation, or suspected to be from state inspectors or surveyors.

Once we successfully make telephone contact with the AFH, staff members are often reluctant to answer screening questions unless they are able to speak with the owner/operator first for authorization. Once a home is contacted that is interested and has a resident who appears to be eligible for treatment, then that resident's durable power of attorney (who may or may not be living locally) must be contacted for consent before any assessment or intervention activities are initiated. Finally, in addition to obtaining consent from the person with power of attorney, the participating staff and residents must themselves also consent/assent to participate in the study.

In our ongoing clinical trial, of 396 AFHs that have been successfully contacted, 197 were ineligible for the SEP study, and 95 refused (not interested or too busy). Reasons for ineligibility included: 89% had no residents with both dementia and sleep disturbances, 5% had residents with sleep disturbances but a non-Alzheimer's type of dementia such as Parkinson's disease, and 6% had residents with sleep problems likely caused by some medical condition not amenable to behavioral intervention, such as severe pain. Seventy-one potentially eligible facilities are in process of considering whether they will participate, and 33 have been enrolled or are pending baseline assessment and randomization. Fifty percent of ineligible and refusing facilities (n=147) have expressed interest in participating in the future if their eligibility or time demands were to change.

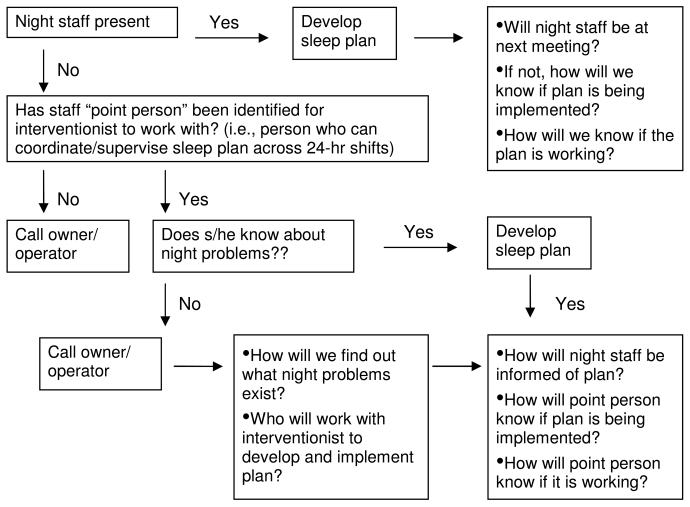

Once research consent has been obtained, the staffing and work scheduling considerations described above also impact other aspects of the research protocol. AFH owners need to be involved with assessments and treatment sessions as well as direct-care staff to increase reporting accuracy as well as staff commitment to treatment program recommendations. Treatment sessions need to be scheduled either with all staff providing nighttime care for residents so treatment continuity is maintained, or with one or more individuals who can effectively communicate the Sleep Education Plan to other team members and monitor its success. Figure 1 shows the algorithm followed in the study to ensure that study interventionists meet with staff who are knowledgeable about resident sleep problems and who can consistently follow the individualized sleep plan collaboratively developed for each resident.

Figure 1.

Sleep Education Program Session 1 treatment algorithm

Finally, to ensure confidentiality, assessment and treatment sessions must be conducted privately (out of earshot of household residents), but at the same time, staff members need to be able to see and respond to any resident problem that arises during the session. Unlike nursing homes which have separate kitchen, housekeeping, administrative, and specialty services (such as recreational, occupational, and physical therapy staff), in many adult family homes the direct care staff who provide residents' personal care and medication management must also cook and serve the meals, clean up the kitchen and living areas, arrange transportation for residents to get to medical appointments, and deal with everyday household mechanical breakdowns. Whereas community-dwelling caregivers typically care for a single older adult, AFHs have multiple residents with a variety of physical, psychological, and cognitive care needs. Consequently, cancelled and rescheduled appointments with research staff due to conflicts, mishaps, or emergencies in the AFH occur with a greater frequency than is found when conducting research in either community or nursing home settings. Thus, treatment needs to be as brief as possible and flexible enough to allow for interruptions, rescheduled sessions, and phone follow-ups when face-to-face meetings cannot be arranged.

Case report

Mrs. A was a 93 year old, white, college-educated resident in a family-owned adult family home. Her Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score 19 was 11/30, indicating severe cognitive impairment. Based upon proxy reports by staff, Mrs. A had high levels of daytime sleepiness on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (total score = 21/24), 20 and she scored in the mildly depressed range on the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (total score = 8/38). 21 In addition to her dementia diagnosis, Mrs. A. had six chronic conditions identified in her resident record, including coronary artery disease, hypertension, diverticulitis, ulcer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and back pain.

Mrs. A's baseline sleep-wake activity was measured using a wrist activity monitors (MicroMini-Motionlogger Actigraph, Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc.), which was worn continuously for 1 week prior to the start of treatment. Average actigraphic sleep estimates for the baseline week were 7.0 hours sleep/night, 77% sleep percent (efficiency), 21 awakenings/night, and 2.1 hours sleep/inactivity during the day.

The AFH in which Mrs. A resided had 6 residents (4 men, 2 women). Staff included a house manager, who functioned as one of the daytime staff, 6 full-time and 1 part-time personal care providers, 1 part-time RN, and 1 “other”. Staff worked 8-hour shifts, with two staff persons on during day/evening shifts, and one at night. The house manager was the primary contact for the study, and took responsibility for working with the interventionist to develop a treatment plan, communicating treatment recommendations to all other staff, and monitoring to see if recommendations were implemented.

The AFH staff were very willing and excited to participate in the study, and the sessions with the interventionist were a free discussion and sharing of ideas. The interventionist told staff that the goal of the study was to make their job easier, and all suggestions were welcome. A sample of the Sleep Education Plan form that was completed by the interventionist based upon brainstorming ideas with staff is included in the Appendix. Staff identified that a light kept on in the resident's room at night might be adversely affecting her sleep. The resident was very attached to the lamp, so staff told her that they needed to check it to make sure it was working properly and removed it; the resident subsequently never asked for it back, and it was returned to her family for safekeeping. They also replaced the curtains in the resident's room to keep out nighttime ambient and street light. Magazines that were of interest to the resident were obtained to offer a stimulating activity to keep her awake during the daytime hours. They introduced other pleasant events and had her help with dishes after each meal. They developed a list of television shows that she enjoyed watching, and that were stimulating to her and that kept her awake. They switched Mrs. A's coffee to decaffeinated and began to take her outside for walks regularly so she could help care for the outdoor plants, since gardening was an activity she had enjoyed in her younger years.

In between sessions, staff often identified and implemented new ideas to improve Mrs. A's sleep. For example, they wondered whether, when Mrs. A awoke at night, the sight of her favorite lazy boy chair in the living room (which she could see when she walked to the bathroom) was drawing her to come out and sit in it. Staff moved the chair from the living room into the dining room (where she couldn't see it from her hallway) each evening after Mrs. A went to bed. She stopped coming out to the living room and would go directly back to bed after using the bathroom. They also began to give Mrs. A her showers in the evening to relax her and to help establish a regular, pleasant bedtime routine.

After 1 month (post-test), Mrs. A.'s 1 week actigraphy records revealed improvements in total sleep time (now 9.0 h/night), sleep efficiency (86%), number of nighttime awakenings (12 awakenings/night), and daytime inactivity (1.4 hrs/day). The staff were very pleased with the improvements in the resident's sleep. Since Mrs. A could now be redirected quickly back to bed, staff no longer had to follow her around the house or repeatedly check to make sure she was not in the living room at night. Similarly, having her closer during the day involved in helping activities meant that it was easier to monitor Mrs. A's safety and care needs while attending to the other AFH residents. The overall result was that it was more enjoyable to have Mrs. A living there.

Discussion

This paper provides clinical and empirical evidence that behavioral strategies including sleep hygiene recommendations, identification of triggers for nighttime awakenings, and modifications in light exposure and physical activity are feasible and may help improve the sleep of persons with dementia who reside in adult family homes. In the provided case example, such strategies yielded both quantifiable improvement at post-test in sleep quality and clinically meaningful improvements in subjective reports about resident sleep that are comparable to those reported for community-dwelling persons with dementia who are treated with nonpharmacological interventions. 22

This paper is only a start of the research that is needed to better understand the challenges faced by small residential care settings like adult family homes that provide care to older adults with dementia-related behavioral disturbances. There is no single national standard for how adult family homes (or their equivalent) should be built, staffed, or managed. They face many of the same difficulties as larger institutions that care for multiple individuals with diverse health and behavioral problems, but do so with fewer employees, less state and federal funding, and less uniformity in physical setting and mandated educational or staff training requirements. Thus, implementing programs like the SEP in different states or even different communities or neighborhoods within a given state could be quite different from the experience described here.

At the same time, adult family homes are a growing industry that offer many of the interpersonal and environmental advantages to residents of remaining in their own private home. Their popularity and increased numbers make them an important target for further study. We are currently enrolling additional subjects and collecting outcome data in a randomized, controlled clinical trial to determine if the SEP is associated with improvements in AFH resident sleep. In the meantime, persons interested in intervening in small residential care settings like adult family homes should be aware that this environment does offer unique assessment and treatment challenges, particularly with regards to staff scheduling, competing work responsibilities, diversity in the cultural and educational backgrounds of front line staff, and complex medical morbidity among residents.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants from the University of Washington (RIFP McCurryS 04 WI), the Alzheimer's Association (IIRG-05-13293), and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH072736). Portions of this paper were presented at the Alzheimer's Association 15th Annual Dementia Care Conference, August 27-29, 2007, Chicago IL.

We acknowledge the hard work and contributions of Northwest Research Group on Aging staff, including June van Leynseele, MA, Thom Walton, BS, Ray Houle, BA, and Felicia Fleming, BA, as well as staff at the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services. We also recognize the thoughtful feedback and suggestions of participating adult family homes, including members of the Washington State Residential Care Council of Adult Family Homes (WSRCC-AFH) and the Adult Family Home Association of Washington (AFHAW).

References

- 1.McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Avery DH, Teri L. Development of behavioral interventions to improve sleep in persons with dementia residing in adult family homes. Gerontologist. 2005;45(Special Issue II):129. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedrick S, Guihan M, Chapko M, et al. Characteristics of residents and providers in the Assisted Living Pilot Program. Gerontologist. 2007;47(3):365–377. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark RF, Turek-Brezina J, Chu CW, Hawes C. Licensed board and care homes: Preliminary findings from the 1991 National Health Provider Inventory. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Research Triangle Institute; Washington, D.C.: Apr 11, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawes C, Wildfire J, Iannacchione V, et al. Report on study methods: Analysis of the effect of regulation on the quality of care in board and care homes. Research Triangle Institute and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: Jan 19, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tornatore JB, Hedrick SC, Sullivan JH, Gray SL, Sales A, Curtis M. Community residential care: Comparison of cognitively impaired and noncognitively impaired residents. Am J Alz Dis Other Dem. 2003;18(4):240–246. doi: 10.1177/153331750301800413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedrick SC, Sales AEB, Sullivan JH, et al. Resident outcomes of medicaid-funded community residential care. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):473–482. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Logsdon RG, Vitiello MV, Teri L. Nighttime Insomnia Treatment and Education for Alzheimer's Disease: A randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:793–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teri L, Logsdon RG, McCurry SM. The Seattle Protocols: Advances in behavioral treatment of Alzheimer's disease. In: Vellas B, Fitten LJ, Winblad B, Feldman H, Grundman M, Giacobini E, editors. Research and practice in Alzheimer's disease and cognitive decline. Vol. 10. Serdi Publisher; Paris: 2005. pp. 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawton MP. Residential environment and self-directedness among older people. Amer Psychol. 1990;45:638–640. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.5.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewinsohn PM, Sullivan JM, Grosscup SJ. Changing reinforcing events: An approach to the treatment of depression. Psychotherapy Theory Res Prac. 1980;17:322–334. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCurry SM, Reynolds CF, Ancoli-Israel S, Teri L, Vitiello MV. Treatment of sleep disturbance in Alzheimer's disease. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4(6):603–608. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2000.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCurry SM, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2003;5:261–272. doi: 10.1007/s11940-003-0017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Logsdon RG, Vitiello MV, Teri L. Training caregivers to change the sleep hygiene practices of patients with dementia: The NITE-AD Project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;10:1455–1460. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hickman SE, Barrick AL, Williams CS, et al. The effect of ambient bright light therapy on depressive symptoms in persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1817–1824. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teri L, Logsdon RG, McCurry SM. Nonpharmacological treatment of behavioral disturbance in dementia. Med Clin N Am. 2002;86:641–656. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richards KC, Sullivan SC, Phillips RL, Beck CK, Overton-McCoy AL. The effect of individualized activities on the sleep of nursing home residents who are cognitively impaired: A pilot study. J Gerontol Nurs. 2001;27(9):30–37. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20010901-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mueller C, Arling G, Kane R, Bershadsky J, Holland D, Joy A. Nursing home staffing standards: Their relationship to nurse staffing levels. Gerontologist. 2006;46(1):74–80. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips C, Lux L, Wildfire J, et al. Report on the effects of regulation on the quality of care: Analysis of the effect of regulation on the quality of care in board and care homes. Research Triangle Institute, Brown University, and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, D.C.: Dec, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psych Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, Shamoian CA. Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23:271–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Vitiello MV, Teri L. Treatment of sleep and nighttime disturbances in Alzheimer's disease: A behavior management approach. Sleep Med. 2004;5(4):373–377. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]