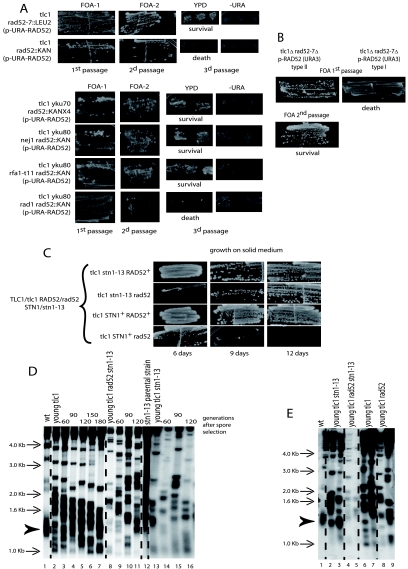

FIG. 7.

Loss of telomere capping promotes the ILT pathway. (A) Top panel, tlc1Δ rad52Δ (either ::LEU2 [first row] or ::KanMX4 [second row]) haploids (originating from a type II-ALT recombining diploid and harboring a centromeric plasmid carrying RAD52-URA3 marker [see Fig. 1B, middle panel]) were challenged for RAD52 plasmid loss on 5-FOA plates for URA3 counterselection. Survivors readily appeared on 5-FOA in the tlc1Δ rad52::LEU2 mutant (first passage, cells photographed 3 days after restreaking) and maintained viability upon subsequent passages (photographed 3 days after second passage). Actual loss of the RAD52-URA3 plasmid was verified on plates lacking uracil. Survivors also appeared in the tlc1Δ rad52::KanMX4 mutant but were not maintained and later died. These results were confirmed in two additional experiments for each strain. Bottom panel, deletion of YKU70 in the tlc1Δ rad52::KanMX4 mutant, illustrated above, led to extrusion of the RAD52-URA3 plasmid and survival (first row). Rows 2 to 4, tlc1Δ rad52::KanMX4 yku80Δ pRAD52-URA3 mutants (the yku80 mutation was used to improve the rate of the ILT pathway) containing, in addition, either the rfa1-t11 or nej1Δ mutation and already recombining in type II, could survive the loss of the RAD52-URA3 plasmid on 5-FOA, while those containing the rad1Δ mutation could not lose the RAD52 plasmid and died. For each of the strains illustrated in the top three rows, the results were confirmed in another experiment, and for the tlc1Δ yku80Δ rad1Δ rad52Δ mutant they were confirmed in three other experiments. (B) Same protocol as for panel A, using tlc1Δ rad52::LEU2 mutants previously recombining either in type II-ALT (left column) or in type I (right column), selected from an agar plate on the basis of their telomere organization by Southern blotting. In contrast to the type II survivors, type I survivors could not extrude the RAD52 plasmid and died (with no survivors appearing even during the first passage). Four experiments for each strain were performed. Telomere organization of the type II-ALT survivors is shown in Fig. 2C. (C) A mixed population of “young” tlc1Δ rad52::LEU2 haploid a cells (prior to senescence onset) and “old” stn1-13 haploid α cells (with telomeres equilibrated in the overelongated state [see panel D, lane 12]) were induced to sporulate without zygote isolation in order to gain time and avoid extensive shortening of the long stn1-13-induced telomeres before analysis (see Fig. 1B, right panel). Spores with the indicated relevant genotype were restreaked every 3 days on agar-based medium (YEPD, 29°C) in order to assess the appearance of postsenescence survivors. At the time the leftmost pictures were taken (6 days had then elapsed since the time of spore selection), the tlc1Δ stn1-13 RAD52+ (first row) and tlc1Δ STN1+ RAD52+ (third row) cells had already undergone a senescence crisis and recombined (not shown), while the tlc1Δ rad52Δ stn1-13 cells were still in senescence crisis (second row). The latter strain generated survivors at the next time point. Meanwhile, the tlc1Δ STN1+ rad52Δ cells (fourth row) died without generating survivors. Although telomeres were initially overelongated to a similar extent in all strains (see panel E), the presence of the stn1-13 mutation was required to allow postsenescence survival in the absence of Rad52 (second row). (D) Initially, telomeric patterns were similar for the tlc1Δ, tlc1Δ rad52Δ stn1-13, and tlc1Δ stn1-13 spores (lanes 2, 8, and 13 [“young”], respectively; the number of generations attained at the time of sample preparation is indicated above each lane). However, the tlc1Δ rad52Δ stn1-13 and tlc1Δ stn1-13 strains exhibited signs of telomeric recombination (lanes 9 to 11 and 14 to 16, respectively) while still having overelongated telomeres. In contrast, the overelongated telomeres of the tlc1Δ RAD52+ STN1+ strain progressively shortened without recombining (lanes 3 to 7). All three tlc1Δ strains contained shorter-than-wild-type telomeres, in addition to their stn1-13-elongated telomeres, inherited from their tlc1Δ rad52Δ parent. The bulk size of wild-type telomeres, around 1.3 kb, is indicated by the arrowhead (lane 1). (E) Telomeric patterns in the four tlc1Δ strains (patterns for two individual spores each are shown) illustrated in panels C and D. All four young tlc1Δ strains are basically undistinguishable from each other (with the exception of tlc1Δ rad52Δ stn1-13 strain, which generated much less material due to poor growth), with all containing both overelongated telomeres inherited from the “old” stn1-13 parent and shorter-than-wild-type telomeres due to the tlc1Δ mutation in the other parent. Data from panel C were confirmed in two other experiments; data from panels D and E were from the cells shown in panel C. A TG1-3 32P-labeled probe was used with XhoI cutting.