Abstract

Protein kinase C δ (PKC δ) modulates cell survival and apoptosis in diverse cellular systems. We recently reported that PKCδ functions as a critical anti-apoptotic signal transducer in cells containing activated p21Ras and results in the activation of AKT, thereby promoting cell survival. How PKCδ is regulated by p21Ras, however, remains incompletely understood. In this study, we show that PKCδ, as a transducer of anti-apoptotic signals, is activated by phosphotidylinositol 3′ kinase/Phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PI3K-PDK1) to deliver the survival signal to Akt in the environment of activated p21Ras. PDK1 is upregulated in cells containing an activated p21Ras. Knockdown of PDK1, PKCδ, or AKT forces cells containing activated p21Ras to undergo apoptosis. PDK1 regulates PKCδ activity, and constitutive expression of PDK1 increases PKCδ activity in different cell types. Conversely, expression of a kinase-dead (dominant-negative) PDK1 significantly suppresses PKCδ activity. p21Ras-mediated survival signaling is therefore regulated by via a PI3K-AKT pathway, which is dependent upon both PDK1 and PKCδ, and PDK1 activates and regulates PKCδ to determine the fate of cells containing a mutated, activated p21Ras.

Keywords: PKCδ, PI3K, Akt, Protein kinase C, Apoptosis, Proliferation

1. Introduction

The protein kinase C (PKC) family, comprised of 12 serine-threonine kinase isozymes, is a prominent target for cancer therapeutics [1]. PKC enzymes are functionally linked to cell growth, differentiation, survival, migration and carcinogenesis. As result, they mediate tumor cell proliferation, survival, drug resistance, invasion and metastasis [2–4]. PKCδ, as a member of the “novel” class of PKC enzymes, can be activated by diacylglycerol (DAG) and by other PKCs. Under physiological conditions, PKCδ can also be activated by various growth factors, via phospholipase C (PLC). PLC stimulates cells to produce DAG and inositol trisphosphate (IP3) from plasma membrane phospholipids, thence activating conventional and novel PKC family members [5, 6]. Conventional PKCs (PKCα and PKCβI/II) predominantly exert anti-apoptotic effects, in part through phosphorylation of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 [7]. In contrast, PKCδ can be pro- or anti-apoptotic, depending upon the cell type or signal received [8]. PKCδ increases the chemotherapeutic sensitivity of a human glioma cell line [9], but promotes survival and resistance to paclitaxel and cisplatin in non-small-cell lung cancers [10]. One recent report suggested that the mechanism through which PKCδ influences cellular proliferation is through regulation of the GL1 protein in Hedgehog signaling [11]. It has alternatively been postulated, in studies using chemical kinase inhibitors, that PKCδ affects the balance of proliferation and apoptosis through regulation of the PI3K-AKT pathway [12].

Phosphoinositide-dependent kinase l (PDK1) is a 63 kDa Ser/Thr kinase ubiquitously expressed in human tissues. It consists of an N-terminal kinase domain and a C-terminal pleckstrin-homology (PH) domain. In vitro, the PH domain binds PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 with higher affinity than other PIs such as PtdIns(4,5)P2. The activity of PDK1 is up-regulated by binding of these PI3K-generated 3′-phosphorylated phospholipids. AKT can be partially-activated by PI3K directly, through phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1), in certain cells. PDK-1 efficiently phosphorylates AKT at Thr-308, and over-expression of PDK1 is sufficient to partially activate AKT in transfected cells [13]. In unstimulated cells, PDK1 is located in both the cytoplasm and at the inner surface of the plasma membrane [14]. We have previously demonstrated that PKCδ is required for cell survival in both p21Ras-transformed cells and in neoplastic cells containing mutated, activated p21Ras, and that PI3K serves as the main downstream effector of the p21Ras oncoprotein to regulate cell survival through PKCδ and ultimately AKT [15]. The functional inter-relationships and relative importance of these signaling kinases components in p21Ras-mediated apoptosis and survival, therefore, has not yet been clarified. In this present work, we report that the balance of p21Ras-mediated survival signaling is regulated by via a PI3K-AKT pathway, which is dependent upon both PDK1 and PKCδ, and that PDK1 activates and regulates PKCδ to determine the fate of cells containing a mutated, activated p21Ras.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmids and reagents

Cell culture reagents were purchased from GIBCO. The anti-PKCδ, and -PDK1 antibodies were ordered from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA); anti-Actin was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); anti-Akt was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rottlerin was purchased from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ). Unless otherwise stated in the text, all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma. PDK1 (wild-type), PDK1-A280V(constitutively-activated), and PDK1-K114G ( kinase-dead) were cloned into the pCDNA vector [16]. These vectors were kindly provided by Dr. F. Liu (University of Texas). The pEGFP-PKCδ vector was the generous gift of Dr. M.E. Reyland (University of Colorado).

2.2. Cell Culture and transfection

Murine fibroblast cell lines NIH/3T3 and Balb were purchased from ATCC. NIH/3T3-Ras and KBalb were produced by stable expression of the v-Harvey Ras and v-Kirsten Ras genes, respectively, in these cell lines. The human pancreatic tumor cell lines MIA PaCa-2 (containing a mutated, activated Kirsten-Ras allele) and BxPc-3 (containing wild-type Ras alleles), and 293T cells were obtained from ATCC. All these cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% donor calf serum and 100 unit/ml penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (InVitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) without serum, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 5–8 hours, the media were replaced with 10% serum. Transient transfectants were lysed 48 h after transfection, or selected in medium containing G418 (0.5mg/ml) for generation of stable clones.

2.3. siRNA knock-down of PKCδ, PDK1 and Akt

293T cells were co-transfected with lentiviral vector pLVTHM containing one of several specific gene-targeted shRNA sequences, and other four “packaging” plasmids for co-expression of the tat, rev, gag/pol and VSV-G gene products. DNA proportions for transfection were 20:1:1:1:2. pLVTHM vectors containing scrambled shRNA sequences were used as controls. After 48 h of transfection, the supernatant fractions containing viral particles were collected every 12 h (2–3 collections) and filtered with 0.45 μm bottle-top filters. Viral supernatant fractions were concentrated by centrifugation for 3 hours at 15,000 × g at 4°C in a Beckman SW28 rotor. Pelleted virions were placed on ice for 30 minutes prior to resuspension with a P200 micropipette and storage at −80°C. The targeting sequences for PDK1, PKCδ and Akt1 were: 5′-AACTGGCAACCTCCAGAGAAT-3′, CTTTGACCAGGAGTTCCTGAA and GAATGATGGCACCTTCATTGG, respectively. Mlu I and Cla I restriction enzyme recognition sequences were added to the termini of these oligonucleotides when they were to be cloned into pLVTHM.

2.4. Assay of PKCδ kinase activity

PKCδ kinase activity was measured with a Kinase Assay kit (Upstate Cell Signaling). Briefly, 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed and PKCδ was immunoprecipitated by a monoclonal PKCδ antibody. The precipitates were incubated with substrate and [γ-33P] ATP for 30 min at 30°C. Incorporation of 33P into the substrates was subsequently quantified by scintillation counting. Kinase assays of immunoprecipitates generated by an β-actin antibody were used as negative controls in these experiments.

2.5. DNA profile analyses

Cells were harvested and resupended in a 35% ethanol/DMEM solution for 5 minutes at room temperature, then stained with propidium iodide at 50 μg/ml containing RNase (25 units/ml) and incubated in the dark for 30 min, then subjected to flow cytometric analysis on a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

2.6. Co-Immunoprecipitation assays

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) plus protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), and proteins of interest were immunoprecipitated by a 1 hr incubation with the respective antibody (2–5 μg/ml), followed by a 30-min incubation with protein A (Sigma). Immune complexes were washed 3 times with Tris-buffered saline and resolved by SDS-PAGE.

2.7. Protein stability assays

Cells were incubated with 100 μg cycloheximide/ml for the time periods indicated. Cell extracts were prepared as above. Proteins (100 μg per lane) were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

2.8. Cell proliferation assays

5×104 cells were plated on 6-well plates and infected with lentivirus expressing PDK1-shRNA or with control shRNA. Cells were enumerated by trypan blue staining from the second day to the sixth day post-infection.

2.9. Statistical Analyses

Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis was performed by using Student’s t-test, and p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. p21Ras-activity up-regulates PDK1 expression, and acts through PDK1 to regulate PKCδ expression

We previously demonstrated that PI3K is the main effector of p21Ras which plays the critical pro-survival role in p21Ras-mediated apoptosis, acting via PKCδ to activate Akt and thereby protecting the cells from apoptotic stimuli [15]. Because PDK1 is a known downstream effector of PI3K, we sought to determine if PDK1 was involved in this tumor survival signaling process. To investigate a role of PDK1, PDK1 expression was assayed in two human pancreatic tumor cells lines: MIA PaCa-2 (containing a mutated, activated p21Ras) and BxPc-3 (containing wild-type p21Ras), and two “matched” pairs of murine cell lines: KBalb (containing a mutated, activated Kirsten p21Ras) and Balb (containing wild-type p21Ras), and NIH-Ras (containing a mutated, activated Harvey p21Ras) and NIH-3T3 cells (containing wild-type p21Ras). PDK1 protein expression in MIA PaCa-2 cells (activated p21Ras) was 60–80% higher than in BxPc-3 cells (Fig. 1A). Levels of PDK1 were also higher in Balb cell lines and NIH/3T3 cell lines expressing an (activated) v-Ki- or v-Ha-p21Ras (respectively) than in their respective parental counterpart cells containing wt-p21Ras (“paired” NIH cell lines not shown).

Fig. 1.

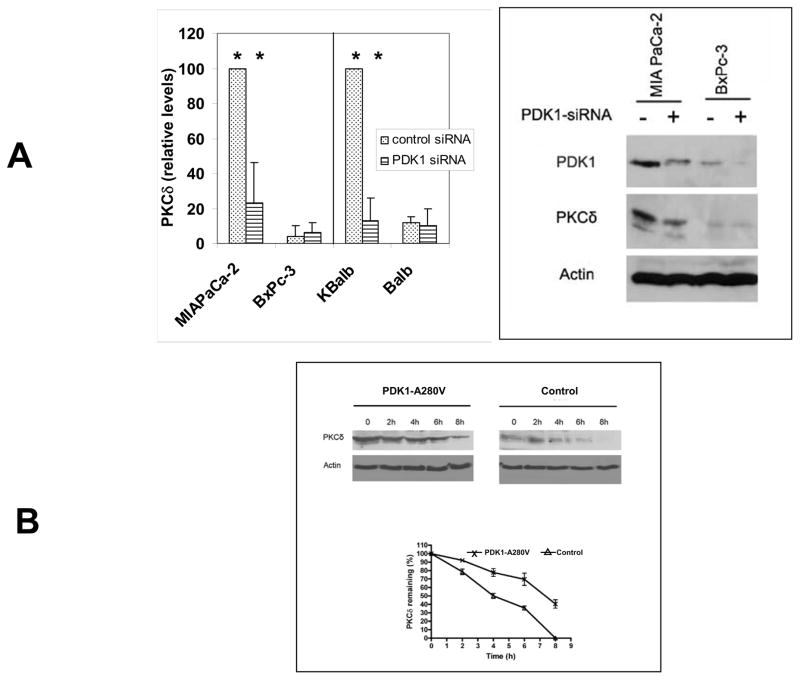

Fig. 1. A. Regulation of PKCδ protein levels by PDK1 in pancreatic cancer cell lines. MIAPaCa-2 (mutant Ras), BxPc-3 (wt-Ras), KBalb (mutant Ras) and Balb (wt-Ras) cells were infected with a lentivirus expressing a PDK1-specific shRNA, or a scrambled shRNA, for 48 h. Cells were harvested and lysed, and the lysates subjected to immunoblotting using antibodies specific for PDK1 or PKCδ. Immunoblotting for β-actin was used as loading control. Left panel: In independent experiments, the intensity of the bands was measured by densitometry and the value of the PKCδ levels in the control siRNA-treated cells was set at 100. Error bars represent SEM. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. * denote p<0.01. Right panel: Representative immunoblot comparing MIAPaCa-2 and BXPc-3 cells.

B. PKCδ protein half-life in cells expressing activated PDK1. Balb cells at confluence, expressing a constitutively-activated PKD1 protein or control vector, were treated with cycloheximide (100 μg/ml) for the indicated lengths of time. Cells were lysed and samples containing equal amounts of total protein (100 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. A representative blot is shown in the top panel. Levels of PDK1 protein as a function of time, after normalization for loading by analysis of β-actin levels, are shown in the lower panel. Error bars represent the S.D. from five independent experiments.

Activated p21Ras or constitutive activation of its effector PI3K, elevate the levels of PKCδ in cells as well as PKCδ kinase activity [15]. When PDK1 levels were knocked down with a specific PDK1-siRNA in a lentiviral vector, PKCδ expression was coordinately decreased at least 50% in the MIA PaCa-2 cells (activated p21Ras) and the KBalb cells (activated p21Ras). In the BxPc-3 and Balb cells, where basal levels of PDK1 were already quite low, no significant effects of PDK1 knockdown on PKCδ levels were detected.

The regulation of PKCδ by PKD1 was not at the level of transcription, as PKCδ transcript levels, assessed by quantitative RT-PCR, did not vary as a function of p21Ras activity (data not shown). To determine if PDK1 affected PKCδ protein stability, the half-life of PKCδ protein was examined in cell lines transfected with either a constitutively active PDK1 (PDK1-A280V) or the empty vector. The half-life of PKCδ was prolonged at least 2-fold in cells expressing an activated PDK1 (Fig. 1B).

3.2. PDK1 associates with PKCδand modulates its activity in cells containing an activated p21Ras protein

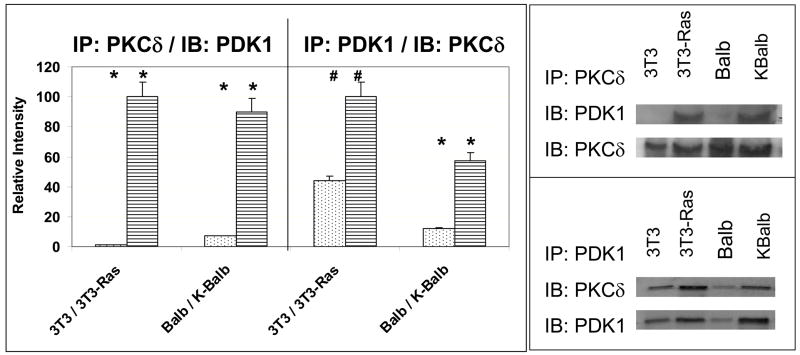

As we have previously demonstrated that PKCδ is required for the activation of Akt by p21Ras, we next asked whether PDK1 is also required for this effect. Co-immunoprecipitation studies using monoclonal antibodies against PKCδ for precipitation of complexes demonstrated an association between PDK1 and PKCδ that was most apparent in the lines containing an activated Ras protein (KBalb and 3T3-Ras) (Fig. 2). The reciprocal experiment, using antibodies against PDK1 for co-immunoprecipitation, followed by immunoblotting with anti-PKCδ antibodies, confirmed this result.

Fig. 2.

Physical association of PDK1 and PKCδ. 400 μg protein from lysates from the four cell lines indicated [Balb (wt-Ras), KBalb (mutant Ras), 3T3 (wt-Ras), and 3T3-Ras (mutant Ras)] were incubated with antibodies against PKCδ or PDK1 for 1 h, then 50 μg Protein-A Sepharose was added to each tube and incubated overnight at 4°C. The precipitates were collected, denatured, separated by PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies against PDK1 or PKCδ. Left panel: In repeated independent experiments, the intensity of the bands was measured by densitometry and the relative values of the PKCδ or PDK1 levels in the control siRNA-treated cells was assessed. Error bars represent SEM. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. * denote p<0.01; # denote p<0.02. Right panel: Representative immunoblots of the reciprocal co-immunoprecipitations.

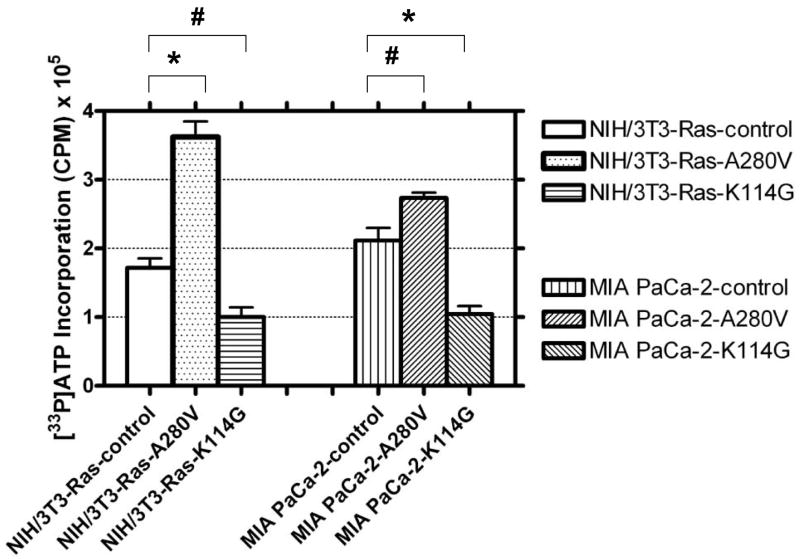

PKCδ activity after perturbation of PDK1 levels or activity was analyzed using a [33P]-labeled kinase assay (Fig. 3). In this study, PKD1 activity was modulated in cell lines containing an activated p21Ras (NIH/3T3-Ras and MIA PaCa-2) by two independent means. Expression of a constitutively-activated PDK1 vector (A280V) was used to enhance PDK1 activity. Conversely, a dominant-negative, kinase-dead PDK1 vector (K114G) was transfected into the cells to repress PDK1 activity. Expression of both the constitutively-active and the dominant-negative PDK1 proteins were verified by immunoblotting (not shown). PKCδ activity increased 35–100% when a constitutively-activated PDK1 protein was expressed. However, in cells expressing a dominant-negative PDK1 kinase-dead vector, endogenous PKCδ activity was decreased by 40–50%. Knockdown of PDK1 protein levels by lentiviral expression of PDK1 siRNA produced comparable decreases in PKCδ activity (not shown).

Fig. 3.

Regulation of PKCδ enzyme activity by PDK1 in cells containing a mutated, activated p21Ras protein. NIH/3T3-Ras and MIA PaCa-2 cells were transfected with the following expression vectors: pCDNA1 (empty vector), pCDNA-PDK1-A280V (constitutively-activated PDK1), or pCDNA-PDK1-K114G (kinase-dead, dominant negative PDK1). At 48 h post-transfection, cells were harvested for analysis. 400 μg of protein lysates were used for immunoprecipitation by PKCδ monoclonal antibodies, and the immunopurified proteins were assayed for activity using an artificial substrate and [γ-33P]-ATP. The mean activities ±SD were obtained from three parallel experiments, and assays from immunoprecipitations using an anti-β-actin antibody were used to determine the background activity, which was subtracted. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. * denote p<0.02; # denote p<0.05.

3.3. PDK1 is required for the association of PKCδ and AKT

We have previously demonstrated a physical association between PKCδ and AKT in cells containing an activated p21Ras protein [15]. Because the data presented above showed regulation of PKCδ activity by PDK1, we next wished to determine whether PDK1 was required for the association of PKCδ and AKT. BxPc-3 cells (wt p21Ras) and MIA PaCa-2 (activated p21Ras) cells were treated with PKCδ-siRNA or PDK1-siRNA, and knock-down of the respective proteins was verified, as shown in the preceding figures. After 48 h, cells were lysed and subjected to co-immunoprecipitation. The association of Akt and PKCδ as demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation was disrupted by knock-down of PDK1 (Fig. 4A). The reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation also confirmed this result. In contrast, PKCδ is not required for the PDK1-AKT association. Whether or not PKCδ levels are suppressed, AKT can be pulled down by the PDK1 antibody (although there was a consistent trend towards a reduction in the association between AKT and PKCδ when PDK1 was suppressed) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. PDK1 is required for the association of PKCδ and Akt.

A: PaCa-2 and BxPc-3 cells were infected with lentiviral vectors expressing a PDK1-specific shRNA or a scrambled shRNA (control). Knockdown of the appropriate target protein was verified by immunoblotting, as demonstrated in preceding figures. After 48 h, cells were harvested and protein associations explored by a co-immunoprecipitation assay.

A. Left side: In repeated independent experiments, the intensity of the bands was measured by densitometry and the relative values of the PKCδ or AKT levels in the control siRNA-treated cells was assessed. The value of the PKCδ or AKT levels in the control siRNA-treated MIA PaCa-2 cells was arbitrarily set at 100. Error bars represent SEM.

Right side: Representative immunoblots of the reciprocal co-immunoprecipitations. Upper panel: anti-AKT antibody was used for immunoprecipitation; Lower panel: PKCδ antibody was used in the immunoprecipitation. Lanes 1 & 2: MIA PaCa-2; Lanes 3 & 4: BxPc-3.

B: MIA PaCa-2 and BxPc-3 cells were infected with lentiviral vectors expressing a PDK1-specific shRNA or a scrambled shRNA (control). After 48 h, cells were harvested and subjected to Co-IP assay. Lanes 1 & 2: MIA PaCa-2; Lanes 3 & 4: BxPc-3.

3.4. PDK1 is required for survival of cells containing activated p21Ras

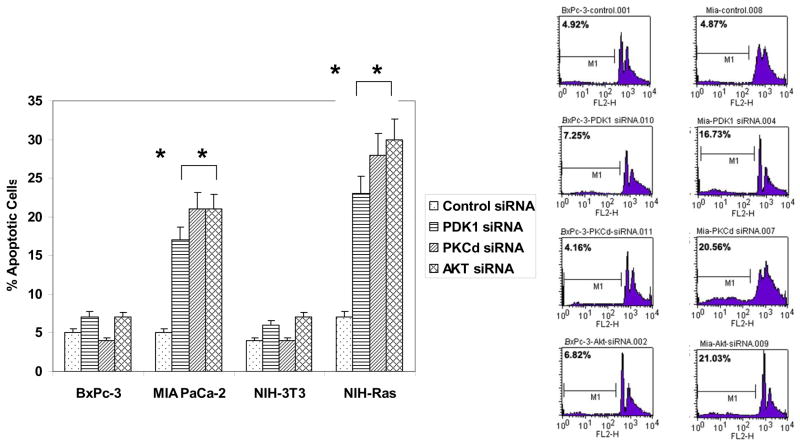

To determine whether PDK1 is required for cell survival in cells containing an activated p21Ras, both BxPc-3 and MIA PaCa-2 were infected by lentivirus expressing a PDK1-specific siRNA or a lentivirus expressing a scrambled siRNA sequence. After 48 h, cells were harvested and subjected to flow cytometric assay by propidium iodide staining. Knockdown of PDK1 by siRNA produced apoptosis in 17% of MIA PaCa-2 cells, as assessed by the fraction of cells with a hypodiploid DNA content, whereas knockdown of PDK1 in tumor cells containing wild-type p21Ras did not alter the baseline levels of apoptosis (7%) (Fig. 5). Knockdown of PKCδ or AKT by siRNA similarly resulted in the significant induction of apoptosis in cells containing activated p21Ras, while having no such effect on the tumor cells containing wt-p21Ras. These results are consistent with our previous study [15]. Similar results, with activated-Ras dependent apoptosis induced by knockdown of PDK1, PKCδ or AKT, were obtained using the matched cell lines NIH/3T3 : NIH/3T3-Ras (+/− activated p21Ras) (and with the Balb : KBalb matched cell lines, not shown).

Fig. 5.

Effects of knock-down of PDK1, PKCδ or AKT on apoptosis of human pancreatic carcinoma cells and murine fibroblasts containing wild-type or activated p21Ras. BxPc-3 (wt-Ras), MIA PaCa-2 (mutant Ras), NIH-3T3 (wt-Ras), and NIH-Ras (mutant Ras) cells were grown to 60–80% confluence in 6-well plates, then infected by lentivirus expressing the respective gene-specific shRNA (specific for PDK1, PKCδ, or AKT) or scrambled shRNA. After 48 h infection, cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide, and the apoptotic (hypodiploid) fractions (M1 fractions) were evaluated by flow cytometry.

Left panel: In repeated independent experiments, the percentages of cells in the M1 fraction was assessed. Error bars represent SEM. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. * denote p<0.01. Right panel: Representative cytometer DNA profiles for BxPc-3 and MIA PaCa-2 cells. Counts refer to cell numbers; FLH2 is a log scale of fluorescence channels.

4. Discussion

The p21Ras proteins control multiple crucial signaling pathways, which can regulate both normal cellular growth/proliferation and also malignant transformation. Point mutations of p21Ras are frequently found in human tumors [17]. The resulting unregulated p21Ras activity contributes to several aspects of the malignant phenotype, including deregulated growth, tumor invasion and programmed cell death [18–21]. Several downstream effectors of constitutively-activated p21Ras in mammalian cells have been identified, including Raf, PI3K, Ral-GDS and phospholipase C (PLC). Our previous studies have shown that PKCδ, by mediating survival signals in p21Ras-transformed cells, is an important regulator in the process of p21Ras-mediated apoptosis [22–24]. Inhibition of PKCδ in transformed cells or tumor cells containing a mutated, activated p21Ras results in apoptosis [15]. Here, we report that higher levels of PDK1 are found in cells expressing an activated p21Ras. PDK1 is known to be activated in cells expressing a oncogenic p21Ras via constitutive activation of the PI3K effector arm. We demonstrate herein that activated PDK1 can up-regulate PKCδ activity and stabilize the protein, and that PDK1 associates with PKCδ and with AKT. Inhibition of PDK1, PKCδ or AKT initiates apoptosis in these cells.

These data, taken together with our previously published studies and those of others, suggest the following signaling model. Mutated p21Ras activates its downstream effector PI3K, which then activates PDK1. While PDK1 is known to be able to phosphorylate AKT directly, thereby partially activating it, full activation of the anti-apoptotic function of AKT in this situation (constitutively-activated p21Ras) also requires PKCδ activity [15]. Levels of PKCδ and its activity are increased by constitutive p21Ras activation, or constitutive PI3K activation alone, as we have shown previously [15]. We demonstrate herein that PDK1 is required for this activation and upregulation of PKCδ by p21Ras, and that the enforced activation of PDK1 is sufficient accomplish this critical activation of PKCδ. The resulting full activation of AKT through the actions of PDK1 and PKCδ provides the required survival signal, without which activated p21Ras would cause programmed cell death in transformed cells.

AKT can be phosphorylated and partially-activated by PDK1 directly, once PDK1 is activated through PI3K [25]. Upon activation of PI3K (by, for example, p21Ras) PtdIns(3,4,5) P3/PtdIns(3,4)P2 are synthesized at the plasma membrane. AKT then interacts through its pleckstrin homology (PH) domain with these lipids, inducing AKT translocation to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane and a coincident conformational change which converts AKT into an accessible substrate for PDK1 action, perhaps by exposing the Thr308 residue of AKT1 for phosphorylation by PDK1 [26], resulting in stabilization of the activation loop. AKT also encodes a hydrophobic motif that must either be phosphorylated to activate the kinase fully [27–29]. This phosphorylation of Ser473 (in AKT1) allows intramolecular binding to occur, resulting in activation. A distinct kinase activity is responsible for this phosphorylation [30], often referred to as ‘PDK2’ activity [31]. The relevant kinase that performs this phosphorylation likely depends upon the cell type and the stimulus. TOR (target of rapamycin), when bound with the adaptor protein rictor [rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (mammalian TOR)], which makes it rapamycin-insensitive, can function as a Ser473 kinase [32,33]. Other kinases that may phosphorylate Ser473 have also been identified, including ILK (integrin-linked kinase) [34,35], PKCβII [36], or even AKT itself through autophosphorylation [37]. AKT can also be phosphorylated on Ser473 by DNA-PK (DNA-dependent protein kinase) following double-strand DNA breaks [38–40].

In contrast to this PI3K-PDK1-PKB(AKT) pathway, the role of PDK1 in PKCδ regulation and its downstream effects on AKT activation, have not yet been fully elucidated. The activation of (conventional) PKCs by PDK1 is a multi-step process. Sonnenburg et al. [41] reported that PDK1 phosphorylation within the activation loop (T-loop) of (conventional) PKCs occurs in a PIP3-independent manner (which therefore mechanistically differs from the phosphorylation of AKT by PDK1, which is PIP3-dependent). PKC T-loop phosphorylation by PDK1 does not fully activate conventional PKCs, but causes the auto-phosphorylation of two serine/threonine residues within the ‘turn motif’ and ‘hydrophobic motif.’ These phosphorylations can then render conventional PKCs fully catalytically competent [42]. We have demonstrated that PKCδ and PDK1 can physically associate, consistent with other reports [43–46], and that this association is enhanced in cells with activating mutations of p21Ras. Might PKD1 directly activate PKCδ in the setting of activated p21Ras? PDK1 can phosphorylate PKCδ on Thr505, and this phosphorylation is stimulated modestly by PIP3, but this phosphorylation contributes little, if at all, to the activity of PKCδ and is not required for its activation [46]. Thus, although constitutive activation of PDK1 is sufficient to activate PKCδ in our system, it may be via an indirect rather than a direct process. We have shown that PKCδ protein levels are elevated in the setting of activated p21Ras, apparently by stabilization of the protein [15], and that the half-life of PKCδ protein is prolonged at least 2-fold in cells expressing an activated PDK1 (this report). Interestingly, Balendran, et al. have reported that PDK1 activity may contribute to the stability of conventional and novel PKC isozymes. In PDK1−/− ES cells, endogenous PKCδ levels (as well as PKCα, PKCβII, PKCE and PKCγ levels) were greatly reduced, due mainly to protein destabilization [47]. Therefore, the studies presented in this report, demonstrating the ability of PDK1 down-regulation to suppress PCKδ protein and activity levels, together with those discussed above, suggest the possibility that this prolongation of PKCδ half-life by p21Ras activity may be mediated through PDK1, and studies are underway to test and elucidate the mechanism.

Brand, et al. recently reported that PKCδ participates in insulin-induced activation of AKT via PDK1 in primary muscle cells, where AKT serves as a regulator of metabolism [43]. Their system demonstrates some interesting mechanistic similarities, and also some differences, when compared to the role of these molecules in p21Ras-mediated regulation of AKT survival signaling. Both insulin and activated p21Ras induce a physical association of AKT and PKCδ, which is PI3K-dependent, and both stimuli induce the physical association of PDK1 and PKCδ, which requires a catalytically-active PKCδ. In both cases, PDK1 may serve to recruit PKCδ to the AKT-PDK1 complex (suggested by serial co-immunoprecipitations in their studies and by knock-down of PDK1 in our studies). Finally, in both cases, activation of AKT by insulin, or by activated p21Ras, requires PKCδ activity. However, activation of PKCδ by insulin is PI3K-independent, and is mediated by SRC [43], whereas activation of PKCδ by p21Ras is PI3K-dependent [15]. Another aspect wherein these systems differ is that insulin induces an increase in the transcription of PKCδ in myotubules [48], whereas p21Ras in tumor cells induces elevation of PKCδ protein post-transcriptionally ([15] and this report).

A more complete understanding of how proliferative and apoptotic signaling pathways are suborned during neoplastic transformation may provide new opportunities for targeted cancer therapeutics. Here, we have shown that the interaction between PDK1 and PKCδ plays an important role in control of p21Ras-mediated apoptosis. Inhibition of PKCδ has been proposed as a promising novel approach for the treatment of cancers containing a mutated p21Ras [15]. These studies raise the possibility that PDK1 may also serve as potential target of therapeutic intervention in tumors with activation of Ras or Ras effector pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant CA112102 from the National Institutes of Health, a Littlefield-AACR Grant in Metastatic Colon Cancer Research, and the Karin Grunebaum Cancer Research Foundation (to D.V.F.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Basu A. Pharmacol Ther. 1993;59:257–280. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90070-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruoslahti E. Princess Takamatsu Symp. 1994;24:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiley SC, Welsh J, Narvaez CJ, Jaken S. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1996;1:177–187. doi: 10.1007/BF02013641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bredel M, Pollack IF. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1997;139:1000–1013. doi: 10.1007/BF01411552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griner EM, Kazanietz MG. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:281–294. doi: 10.1038/nrc2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neri LM, Borgatti P, Capitani S, Martelli AM. Histol Histopathol. 2002;17:1311–1316. doi: 10.14670/HH-17.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruvolo PP, Deng X, Carr BK, May WS. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25436–25442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wert MM, Palfrey HC. Biochem J 352 Pt. 2000;1:175–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandil R, Ashkenazi E, Blass M, Kronfeld I, Kazimirsky G, Rosenthal G, Umansky F, Lorenzo PS, Blumberg PM, Brodie C. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4612–4619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark AS, West KA, Blumberg PM, Dennis PA. Cancer Res. 2003;63:780–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riobo NA, Haines GM, Emerson CP., Jr Cancer Res. 2006;66:839–845. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringshausen I, Schneller F, Bogner C, Hipp S, Duyster J, Peschel C, Decker T. Blood. 2002;100:3741–3748. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alessi DR, Deak M, Casamayor A, Caudwell FB, Morrice N, Norman DG, Gaffney P, Reese CB, MacDougall CN, Harbison D, Ashworth A, Bownes M. Curr Biol. 1997;7:776–789. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Currie RA, Walker KS, Gray A, Deak M, Casamayor A, Downes CP, Cohen P, Alessi DR, Lucocq J. Biochem J. 1999;337:575–583. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia S, Forman LW, Faller DV. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13199–13210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610225200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wick MJ, Dong LQ, Riojas RA, Ramos FJ, Liu F. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40400–40406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bos JL. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbacid M. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1987;56:779–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.004023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forrester K, Almoguera C, Han K, Grizzle WE, Perucho M. Nature. 1987;327:298–303. doi: 10.1038/327298a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bos JL. Mutat Res. 1998;195:255–71. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(88)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shields JM, Pruitt K, McFall A, Shaub A, Der CJ. Tr Cell Biol. 2000;10:147–54. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liou JS, Chen JS, Faller DV. J Cell Physiol. 2004;198:277–294. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen CY, Faller DV. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15320–15328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liou JS, Chen CY, Chen JS, Faller DV. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39001–39011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alessi DR, James SR, Downes CP, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, Cohen P. Curr Biol. 1997;7:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanhaesebroeck B, Alessi DR. Biochem J. 2000;346:561–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J, Cron P, Thompson V, Good VM, Hess D, Hemmings BA, Barford D. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1227–1240. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00550-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alessi DR, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, Hemmings BA. EMBO J. 1996;15:6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Nature. 2001;411:355–365. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams MR, Arthur JS, Balendran A, van der Kaay J, Poli V, Cohen P, Alessi DR. Curr Biol. 2000;10:439–448. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong LQ, Liu F. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E187–E196. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacinto E, Lorberg A. Biochem J. 2008;410:19–37. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delcommenne M, Tan C, Gray V, Rue L, Woodgett J, Dedhar S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11211–11216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch DK, Ellis CA, Edwards PA, Hiles ID. Oncogene. 1999;18:8024–8032. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawakami Y, Nishimoto H, Kitaura J, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Kato RM, Littman DR, Leitges M, Rawlings DJ, Kawakami T. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47720–47725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan TO, Tsichlis PN. Sci STKE 2001. 2001:E1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.66.pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bozulic B, Surucu D, Hynx BA, Hemmings Mol Cell. 2008;30:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng J, Park J, Cron P, Hess D, Hemmings BA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41189–41196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huston E, Lynch MJ, Mohamed A, Collins DM, Hill EV, MacLeod R, Krause E, Baillie GS, Houslay MD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12791–12796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805167105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sonnenburg ED, Gao T, Newton AC. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45289–45297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Behn-Krappa A, Newton AC. Curr Biol. 1999;9:728–737. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80332-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brand C, Cipok M, Attali V, Bak A, Sampson SR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:954–962. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belham C, Wu S, Avruch J. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R93–R96. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Good JA, Ziegler WH, Parekh DB, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Parker PJ. Science. 1998;281:2042–2045. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stempka L, Girod A, Muller HJ, Rincke G, Marks F, Gschwendt M, Bossemeyer D. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6805–6811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balendran A, Hare GR, Kieloch A, Williams MR, Alessi DR. FEBS Lett. 2000;484:217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horovitz-Fried M, Cooper DR, Patel NA, Cipok M, Brand C, Bak A, Inbar A, Jacob AI, Sampson SR. Cell Signal. 2006;18:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]