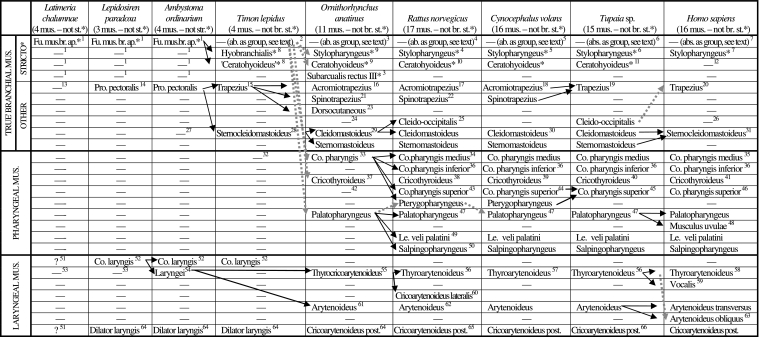

Table 3.

Scheme illustrating the authors’ hypotheses regarding the homologies of the branchial, pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles of adults of representative sarcopterygian taxa (see caption of Table 1, text, and Figs 3–17; ab. = absent; ap. =apparatus; br. = branchial; co. = constrictor; fu. = functional; le. = levator; mus. = muscles; post. = posterior; pre. = present; pro. = protractor; st =sensu stricto)

1[adult bony fish and amphibians often have various branchial muscles sensu stricto, e.g. the constrictores branchiales, levatores arcuum branchialium, transversi ventrales and/or subarcuales recti, among others: e.g. Edgeworth 1935; Kesteven 1942–1945]

2[absent as a group; adult lizards such as Timon lack all the branchial muscles sensu stricto except the hyobranchialis and ’ceratohyoideus’: these two muscles are seemingly the result of a subdivision of the subarcualis rectus I: see text]

3[absent as a group; the only branchial muscles sensu stricto that are present as independent structures in adult monotremes such as the platypus are the subarcualis rectus III, the ceratohyoideus, and seemingly the stylopharyngeus: see text; these two latter muscles seem to be the result of a subdivision of the subarcualis rectus I; it should be noted that a subarcualis rectus II is present in extant mammals such as marsupials: e.g. Edgeworth 1935]

4[absent as a group; the only branchial muscles sensu stricto that are present as independent structures in adult rodents such as the Norwegian rat are the ceratohyoideus and seemingly the stylopharyngeus: see text]

5[absent as a group; the only branchial muscles sensu stricto that are present as independent structures in adult colugos are the ceratohyoideus and seemingly the stylopharyngeus: see text]

6[absent as a group; the only branchial muscles sensu stricto that are present as independent structures in adult tree-shrews as Tupaia are the ceratohyoideus and seemingly the stylopharyngeus: see text]

7[absent as a group; the only branchial muscle sensu stricto that is present as an independent structure in adult modern humans is seemingly the stylopharyngeus: see text]

8 (part or totality of subarcualis rectus I or of branchiohyoideus sensuEdgeworth 1935 and Herrel et al. 2005) [see text]

9[the data now available on innervation, development, topology and comparative anatomy indicate that the mammalian stylopharyngeus is probably not a de novo pharyngeal muscle sensu Edgeworth, but instead a derivative of the branchial muscles sensu stricto: see text]

10 (the ceratohyoideus sensuHouse 1953 corresponds to the branchiohyoideus sensuSprague 1943 and to the hyoideus latus, keratohyoideus brevis and intercornualis sensuSaban 1968) [see text]

11 (interhyoideus sensuLe Gros Clark 1926) [see text]

12[absent as an independent muscle in modern humans, but present in other primates: e.g. Sprague 1944b; Saban 1968]

13[the protractor pectoralis is not present as an independent structure in Latimeria, but it is present in numerous sarcopterygians and actinopterygians and was very likely present in the common ancestor of these two groups: e.g. Edgeworth 1935; Straus & Howell 1936; Diogo 2007]

14 (cucullaris sensuEdgeworth 1935)

15 (capitodorsoclavicularis sensuTsuihiji 2007)

16 (anterior trapezius sensuSaban 1971) [the anterior and posterior trapezius sensuSaban 1971, are well separate in platypus and clearly correspond to the acromiotrapezius and spinotrapezius of other mammals; according to Edgeworth 1935 in monotremes the subarcualis I derives from the branchial arch 1, while the subarcualis III, trapezius and sternocleidomastoideus derive from the branchial arch 3; but see text]

17 (dorsoscapularis superior, anterior trapezius or trapezius superior sensuGreene 1935) [it is somewhat mixed with the spinotrapezius, but is considered as a separate muscle by many authors, see e.g. Greene 1935; according to Edgeworth 1935 in placentals the subarcualis I usually derives from the branchial arch 1 (in some cases it may atrophy during development as e.g. in Manis and seemingly in most anthropoids, including modern humans), while the acromiotrapezius, spinotrapezius, cleido-occipitalis, cleidomastoideus, sternomastoideus and sternocleidomastoideus derive from the branchial arch 2; also according to Edgeworth 1935 in certain adult placentals as e.g. Sus there is a single branchial arch, which gives rise to all the muscles listed above; but see text]

18[contrary to what is stated by Macalister 1872 and Gunnell & Simmons 2005 in the colugos dissected by us both the spinotrapezius and the acromiotrapezius are present as independent structures: the former mainly inserts on the scapular spine, while the latter mainly inserts on the acromion; this is also the case in the specimens examined by e.g. Leche 1886: see his fig. 8; as stated by Macalister 1872 in colugos the trapezius complex (= acromiotrapezius + spinotrapezius of the present work) does not reach the cranium anteriorly and does not attach on the clavicle posteriorly; i.e. this trapezius complex does not include a ’cleido-trapezius’sensuKardong 2002 and does not seem to include the cleido-occipitalis sensu the present work]

19[in both Tupaia and Ptilocercus, it is a single, continuous muscle, which seems to correspond to the acromiotrapezius + spinotrapezius of other mammals: e.g. Le Gros Clark 1924, 1926; George 1977; this work]

20[it has 3 parts, i.e. the acromiotrapezius, claviculotrapezius and spinotrapezius sensuKardong 2002, which are not differentiated into separate muscles, as is the case in various other mammals; the human ’claviculotrapezius’ probably corresponds to part of the trapezius of e.g. Tupaia, although it may possibly correspond to the cleido-occipitalis of this latter taxon: e.g. Jouffroy 1971]

21 (posterior trapezius sensuSaban 1971: see 16)

22 (dorsoscapularis, inferior posterior trapezius or trapezius inferior superior sensuGreene 1935) [see 17]

23[present in monotremes as well as in some other extant mammals; seemingly corresponds to part of the trapezius of tetrapods such as lizards: e.g. Jouffroy 1971; Jouffroy & Lessertisseur 1971]

24[according to Edgeworth 1935 the cleido-occipitalis of mammals as e.g. Tatusia seems to correspond to part of the reptilian trapezius, but the ’cleido-occipitalis’ of e.g. the placental carnivores may well correspond to the part of the reptilian sternocleidomastoideus]

25 (the cleido-occipitalis sensu Wood 1870 and Edgeworth 1935 corresponds to the clavotrapezius and cleido-occipitalis cervicalis sensuGreene 1935) [the position and orientation of the fibers of the cleido-occipitalis of e.g. Rattus and Tupaia are more similar to those of the monotreme sternocleidomastoideus than to those of the monotreme trapezius; also, according to Greene 1935 in e.g. rats the cleido-occipitalis, sternomastoideus and cleidomastoideus are all innervated by the ‘spinal accessory and third and fourth cervical nerves through the subtrapezial plexus’, while the spinotrapezius and acromiotrapezius are innervated by the ‘spinal accessory and second and third cervical nerves through the subtrapezial plexus’]

26[usually absent as an independent muscle, but may be found in a few modern humans: e.g. Wood 1870]

27[according to Howell 1933–1937, the sternocleidomastoideus is only present as a separate muscle in reptiles and mammals, being derived from the protractor pectoralis]

28 (episternocleido-mastoideus sensuHerrel et al. 2005; capiticleidoepisternalis sensuTsuihiji 2007)

29[as suggested by Howell 1937a and Saban 1971, in the platypus specimens dissected by us both the sternomastoideus and cleidomastoideus are present as independent structures]

30[contrary to what is suggested in Leche's 1986 fig. 4, the colugos dissected have both a sternomastoideus and a cleidomastoideus, which are well separated; each of these muscles attaches anteriorly on the mastoid process by a thin and long tendon]

31[including sternal and clavicular heads, which clearly seem to correspond to the sternomastoideus and cleidomastoideus of other mammals, but are not really differentiated into independent muscles]

32[plesiomorphically reptiles have no muscular pharynx; reptiles such as crocodilians do possess a secondary palate and a means to constrict the pharynx, but this constrictor is a derivative of an hyoid muscle, the interhyoideus: e.g. Schumacher 1973; Smith 1992]

33[there is only one constrictor of the pharynx in monotremes, but the cricothyroideus and the palatopharyngeus are already differentiated in these mammals; some authors consider that amphibians may have ’pharyngeal muscles’ lying between the hyoid apparatus and the pharyngeal wall: e.g. Piatt 1938; Smith 1992; however, these ’pharyngeal muscles’ seem in fact to be branchial muscles sensu stricto as e.g. the levatores arcuum branchialium and/or the transversi ventrales sensu Edgeworth, 1935: see e.g. Saban, 1971, p. 708]

34 (ceratopharyngeus and/or hyopharyngeus sensuHouse 1953)

35[including the pars ceratopharyngea and the pars chondropharyngea sensuTerminologia Anatomica 1998, which insert on the hyoid bone and on the thyroid cartilage, respectively]

36[as described by Saban 1968, the constrictor pharyngis inferior of therian mammals is often divided into a pars thryropharyngea attaching on the thyroid cartilage, a pars cricopharyngea attaching on the cricoid cartilage, and a pars intermedia lying between these two myological structures; the pars intermedia is often reduced in mammals as e.g. primates and is often absent in mammals as e.g. rodents]

37[in the platypus specimens dissected by us the cricothyroideus is seemingly not divided into a pars obliqua and a pars recta; it should be noted that in terms of both its ontogeny and phylogeny the mammalian cricothyroideus is clearly a pharyngeal muscle, and not a laryngeal muscle as it is sometimes suggested in the literature: e.g. Edgeworth 1935; Negus, 1949; DuBrul 1958; Starck & Schneider 1960; Saban 1968; Wind 1970; Crelin 1987; Harrison 1995]

38[including a pars obliqua and a pars recta: see 39]

39[including a pars obliqua and a pars recta, which are more separated than in Rattus and Tupaia but are not as separated as in modern humans]

40[including a pars obliqua and a pars recta: see 39]

41[including a pars obliqua and a pars recta: see 39]

42[according to Edgeworth 1935 the constrictor pharyngis superior is missing in monotremes and was very likely poorly developed in the first placentals, being probably similar to the ’glossopharyngeus ’of e.g. rats; according to that author the constrictor pharyngis superior only became a broad muscle as that found in e.g. modern humans later in evolution; House 1953 and Smith 1992 suggest that the pterygopharyngeus of e.g. rats probably correspond to part of the constrictor pharyngis superior of modern humans; in our opinion it is more plausible to assume that the pterygopharyngeus became part of the human constrictor pharyngis superior (see e.g. Fig. 15) than to assume that a muscle such as the ’glossopharyngeus’ of rats migrated superiorly in order to attach on the hard palate; however, until more data are available, one cannot completely discard the hypothesis that the pterygopharyngeus of e.g. rats and colugos might be simply missing or deeply mixed with the palatopharyngeus in mammals such as Tupaia and Homo]

43 (glossopharyngeus sensuHouse 1953) [the constrictor pharyngis superior of rats seemingly includes only a pars glossopharyngea: see 42]

44[our dissections indicate that it includes a pars glossopharyngea and possibly a pars buccopharyngea]

45[seemingly includes a pars buccopharyngea, a pars pterygopharyngea (corresponding to the pterygopharyngeus of e.g. rats and colugos? see 42), and possibly a pars glossopharyngea: e.g. Sprague 1944a; this work]

46[includes a pars buccopharyngea, a pars pterygopharyngea (corresponding to the pterygopharyngeus of e.g. rats and colugos? see 42), a pars mylopharyngea, and a pars glossopharyngea]

47[more mixed with the salpingopharyngeus than in modern humans]

48[according to Edgeworth 1935 this muscle is only found in a few mammals such as primates, corresponding to part of the palatopharyngeus of other mammals]

49[corresponds to part of the palatopharyngeus of monotremes: e.g. Edgeworth 1935; Saban 1968; this work]

50[corresponds to part of the palatopharyngeus of monotremes: e.g. Edgeworth 1935; Saban 1968; this work]

51 Present? Some non-sarcopterygian vertebrates as e.g. Polypterus have a ’constrictor laryngis’ and/or a ‘dilatator laryngis’, but it is not clear if these muscles actually correspond to the constrictor laryngis and dilatator laryngis of sarcopterygians and thus if these latter muscles are plesiomorphically present in osteichthyans: e.g. Edgeworth 1935; the few descriptions of the laryngeal region of Latimeria chalumnae do not allow us to appropriately discern if these muscles are, or are not, present in this taxon: e.g. Millot & Anthony 1958]

52[recent developmental works indicate that in amphibians as e.g. salamanders and reptiles as e.g. chickens laryngeal muscles such as the dilatator laryngis are at least partially derived ontogenetically from somites and possibly also from branchial mesoderm: e.g. Piekarski & Olsson 2007; the ontogenetic derivation of these muscles is thus actually similar to that of muscles such as the protractor pectoralis of amphibians and the trapezius/sternocleidomastoideus of reptiles: see text; according to e.g. Piekarski & Olsson, 2007 in some cases the constrictor oesophagus might also be at least partially derived ontogenetically from somites]

53[the laryngei of tetrapods does not seem to be plesiomorphically found in sarcopterygians, because it is absent in sarcopterygian fish as dipnoans; a detailed study of the laryngeal region of Latimeria is however needed in order to support, or to contradict, this hypothesis: see 51]

54[the laryngei and constrictor laryngis of amphibians derive ontogenetically from the same anlage: e.g. Edgeworth 1935]

55 (the thyrocricoarytenoideus sensuSaban 1968 corresponds to the thyroarytenoideus sensuEdgeworth 1935; it has two bundles, which seemingly correspond to the thyroarytenoideus and cricoarytenoideus lateralis of other mammals: that is why we prefer to use the name thyrocricoarytenoideus for the monotreme muscle) [Smith 1992, p. 340, states, that ‘the laryngeal muscles of mammals and amphibians are innervated by two homologous branches of cranial nerve X, the superior and inferior (or recurrent) laryngeal nerves; in contrast in reptiles (except in Aves) the innervation of the larynx is via a single laryngeal nerve that is a branch of cranial nerve IX’; this supports Edgeworth's 1935 view that the ’laryngei’ of reptiles is not homologous to that of amphibians and thus to the thyrocricoarytenoideus + arytenoideus of monotremes]

56[mainly divided into superficial and deep bundles]

57[divided into a posterior, medial bundle, and an anterior, lateral part, which seem to correspond respectively to the pars intermedia and pars superioris of fig. 69 of Starck & Schneider 1960; the latter bundle is in turn subdivided into a medial bundle and a lateral bundle, the latter being fused with the cricoarytenoideus posterior and thus seemingly corresponding to the ceratoarytenoideus lateralis sensuHarrison 1995]

58[often includes a pars thyroepiglottica, a pars aryepiglottica, a pars superioris, a pars ventricularis and/or a ceratoarytenoideus lateralis sensuSaban 1968 and Harrison 1995]

59 (thyroarytenoideus inferior sensuSaban 1968) [according to e.g. Edgeworth 1935 the vocalis is only found in a few taxa such as some primates, and corresponds to the medial portion of the thyroarytenoideus of other mammals]

60 (cricoarytenoideus ventralis sensuWhidden 2000) [see 55]

61 (interarytenoideus sensuSaban 1971 which is divided into crico-pro-arytenoideus and ary-pro-arytenoideus)

62 (interarytenoideus sensuEdgeworth 1935)

63[it is commonly accepted that the arytenoideus transversus and arytenoideus obliquus derive from the arytenoideus of other mammals; however, as the pars aryepiglottica is seemingly derived from the thyroarytenoideus, the possibility that the arytenoideus obliquus also derives from this latter muscle, and not from the arytenoideus cannot be ruled out: e.g. Saban 1968]

64 (cerato-crico-arytenoideus sensuSaban 1971) [the cricoarytenoideus posterior of mammals corresponds to the dilatator laryngis of reptiles, amphibians and dipnoans, which is not homologous to the ‘dilatator laryngis’ of the actinopterygians Amia and Lepisosteus nor to the ‘dilatator laryngis’ of the actinopterygian Polypterus, according to Edgeworth 1935]

65 (cricoarytenoideus dorsalis sensuWhidden 2000)

66[including the ceratocricoideus sensuHarrison 1995, which, according to this author, is found in about 63% of modern humans]