Summary

Two naturally-occurring compounds--curcumin (the active ingredient in the spice turmeric) and the green tea extract epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) have marked effects on the apoptotic machinery in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). These results provide a preclinical foundation for future clinical use of these compounds in this disease.

Current treatments for B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) include purine analogues (fludarabine) and monoclonal antibodies (rituximab) (1). While people can live for years with B-CLL, there is no effective cure. Hence, new targeted therapies are vital to improving clinical outcomes for patients with B-CLL. In this issue of Clinical Cancer Research, Ghosh et al. (2) investigate, in the preclinical setting, a novel approach to treating B-CLL that combines two naturally-occurring compounds: curcumin and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG). Using natural compounds for the treatment of cancer is not new. Sixty-two percent of cancer drugs approved by the U.S. FDA between 1981 and 2002 were of natural origin (3). For example, all-trans retinoic acid, which is a vitamin A derivative, is a very effective treatment for acute promyelocytic leukemia. A wealth of data supports a role for curcumin, the active ingredient in the spice turmeric, as an anti-neoplastic agent (4,5). This work extends previous observations by examining the molecular pathways involved in curcumin-induced apoptosis of B-CLL cells. In particular, in primary CLL cultures, curcumin inhibited expression of pro-urvival molecules, including STAT3, Akt, and NF-κB, as well as the anti-apoptotic proteins Mcl-1 and XIAP. Curcumin also up-regulated the pro-apoptotic protein, BIM. Sequential administration of EGCG followed by curcumin resulted in increased CLL cell death and neutralized stromal protection.

Curcumin has impressive antioxidant, chemo-preventive, chemotherapeutic, and chemo-sensitizing activities (4,5). The apoptosis of B-CLL cells induced by curcumin is dose-dependent, and normal B lymphocytes are less sensitive to its cytotoxic effects than B-CLL cells (2,6). Curcumin induces PARP cleavage in primary B-CLL cells (2), reflecting the activation of programmed cell death. PARP cleavage is induced by curcumin in other tumor types, including pancreatic and colorectal cancer (7–9). Interestingly, the authors did not observe activation of upstream caspases following curcumin treatment. This differs from several other studies that demonstrate specific caspase-3 activation by curcumin in HL-60 and other tumor cell lines (4,5,10). In primary B-CLL, the mechanism of PARP cleavage remains unclear. Other cellular events that contribute to curcumin-induced apoptosis include the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondrial membrane. This occurs in several different cell lines following treatment with curcumin, as do changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (4,5). The role of mitochondrial events in curcumin-induced apoptosis in B-CLL cells was not examined in this study.

Curcumin also inhibits the constitutive activation of pro-survival pathways, some of which are preferentially active in primary B-CLL cells, including STAT3, Akt, and NF-κB. Constitutive activation of STAT3 has been reported in several cancers, including breast, prostate, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, multiple myeloma, and pancreatic cancer (4,8,11). STAT3 plays an important role in the induction of anti-apoptotic genes and angiogenic factors, and is vital to various cytokine signaling pathways (4,5,11). Curcumin effectively inhibits constitutive STAT3 phosphorylation in B-CLL (2), agreeing with other studies which demonstrate that curcumin is an effective inhibitor of STAT3 function (4,5,11). Mcl-1, a pro-survival gene downstream of STAT3, is also down-regulated by curcumin in primary B-CLL (2). Constitutive phosphorylation of Akt is down-regulated by curcumin in primary B-CLL cells (2) and other tumors including non-Hodgkin’s B cell lymphoma, prostate cancer, and renal cell carcinoma (4). However, curcumin can also induce its pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative effects without perturbing Akt phosphorylation status (5,7,12).

A pro-survival molecule that seems to be universally inhibited by curcumin is the NF-κB transcription factor. NF-κB is down-regulated by curcumin in many different cancers (4–8,11). Constitutive phosphorylation of IκBα in primary B-CLL cells is inhibited by curcumin, indicating that genes downstream of NF-κB should be inhibited in these cells. Indeed, XIAP, a downstream target of NF-kB, is down-regulated in primary B-CLL following curcumin treatment (2). The lack of down-regulation of Bcl-2 by curcumin is an interesting finding considering previous work demonstrating that Bcl-2 is a direct transcriptional target of NF-κB and is down-regulated by curcumin (4,5). BIM, a pro-apoptotic protein, is up-regulated by curcumin in primary B-CLL. Hence, curcumin can down-regulate survival pathways and up-regulate apoptotic pathways in B-CLL.

What happens to the effectiveness of curcumin treatment when B-CLL cells are co-cultured in the context of the stromal environment? Stromal cells typically maintain an anti-apoptotic environment through direct contact and through soluble mediators. Co-culture of B-CLL cells with stromal cells provided substantial protection from curcumin-induced apoptosis at lower curcumin doses, but not at higher doses (20μM) (2). These results lend insight into the effect of the host environment on curcumin-induced apoptosis, and also indicate that higher doses of curcumin may be required to achieve the level of apoptosis seen in vitro.

It is unlikely that curcumin alone will be an effective treatment for B-CLL due to incomplete apoptotic responses. Curcumin itself enhances the effectiveness of a variety of compounds, including vincristine in B-CLL in vitro (6). Natural agents, like curcumin, are desirable candidates for adjuncts to chemotherapy because of their negligible toxicities. EGCG, the principal polyphenol in green tea, induces apoptosis in B-CLL cells in vitro through partial inhibition of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 phosphorylation, and also by caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage. Bcl-2 is down-regulated by EGCG, as is Mcl-1 and XIAP (2). Treatment of primary B-CLL cells with the combination of EGCG and curcumin was investigated. The sequential administration of EGCG followed by curcumin was the most effective treatment combination; whereas simultaneous administration resulted in antagonistic effects.

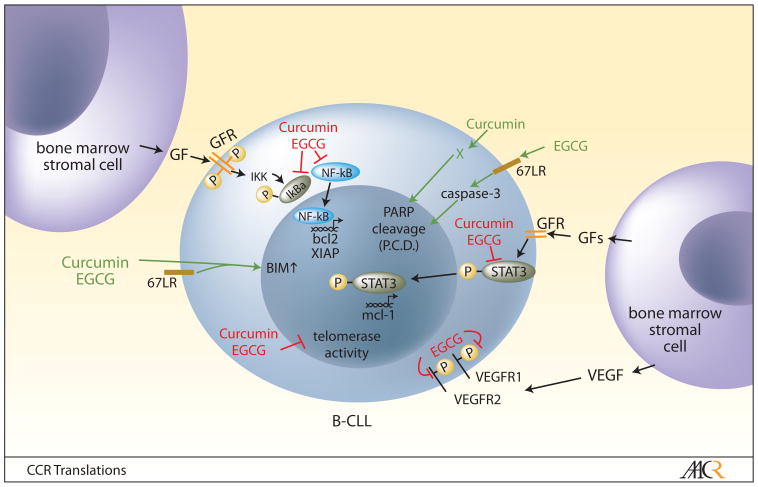

EGCG and curcumin target many of the same molecular pathways, including induction of PARP cleavage and the inhibition of telomerase activity (2,4,5,10). While EGCG and curcumin down-regulate many common survival pathways, including STAT3, Akt, NF-κB, and the anti-apoptotic genes Mcl-1 and XIAP, not all of their targets overlap (Figure 1.). For example, while both compounds induce PARP cleavage and apoptosis in B-CLL, EGCG accomplishes this through activation of caspase-3, while curcumin does not induce caspase-3 activation in these cells (2). Thus, these two natural agents have many pathways in common, but can diverge from each other as well, and can potentially exhibit opposing effects. Hence, further study of the molecular mechanisms involved in the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of these agents is warranted.

Figure 1.

Bone marrow stromal cells provide pro-survival and anti-apoptotic signals to B-CLL cells. Curcumin and EGCG inhibit pro-survival pathways (red) and induce pro-apoptotic pathways (green). GF=growth factor, GFR=growth factor receptor, 67LR=67kDa laminin receptor, BIM=Bcl-2-interacting mediator of apoptosis, XIAP=X linked inhibitor of apoptosis, PARP= poly (ADP ribose) polymerase, P.C.D.=programmed cell death, VEGFR=vascular endothelial cell growth factor receptor, b.m=bone marrow, STAT3=signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, Mcl-1=myeloid cell leukemia–1, IKK=inhibitory κB kinase.

Clinical trials with curcumin and EGCG as individual agents, or in combination with standard chemotherapy, are already underway in several cancers (4,5,11, and clinical trials.gov). A phase II clinical trial of curcumin in advanced pancreatic cancer was recently published by our group and demonstrated a patient with a 73% tumor regression, and another patient who was stable on curcumin for more than 2.5 years (11, and Kurzrock personal communication). No side effects were observed. However, overall response rates were low, perhaps because curcumin absorption after oral administration is poor (11).

Oral green tea extracts have been taken voluntarily by patients with B-CLL, and EGCG has already begun phase I clinical trials in Rai stage 0-II patients with B-CLL (2). The current study provides rationale for the combination of curcumin plus EGCG in the clinical setting, and provides information concerning the dose and administration of these two compounds. A constant ratio of 10:1 (EGCG:curcumin) was established as effective at inducing apoptosis in B-CLL. Sufficiently high doses of EGCG and of circulating curcumin will be necessary to overcome stromal protection in vivo. The data also indicate that sequential treatment of B-CLL with EGCG followed by curcumin is preferable to simultaneous treatment, and is crucial to the efficacy of the combination of these two compounds. Simultaneous treatment of B-CLL cells with EGCG and curcumin resulted in antagonistic effects. Ultimately, however, the optimal studies will probably require the use of a curcumin compound modified to enhance its bioavailability. Encapsulating curcumin in liposomes allows it to be administered systemically, and several groups are working on altering curcumin to increase its absorption when taken orally (4,5,9,13). Based on the biologic properties of curcumin alone or in combination with EGCG or other compounds, these second generation curcumin moieties should be explored for the treatment of CLL and other cancers.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible in part by Grant Number RR024148 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR)1, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/.

References

- 1.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the international workshop on chronic lymphocytic leukemia updating the national cancer institute working group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111:5446–55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh AK, Kay NE, Secreto CR, Shanafelt TD. Curcumin inhibits pro-survival pathways in B-CLL and has the potential to overcome stromal protection of CLL B-cells in combination with EGCG. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1511. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzales GF, Valerio LG., Jr Medicinal plants from Peru: a review of plants as potential agents against cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2006;6:429–44. doi: 10.2174/187152006778226486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatcher H, Planalp R, Cho J, Torti FM, Torti SV. Curcumin: From ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1631–52. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunnumakkara AB, Anand P, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin inhibits proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis of different cancers through interaction with multiple cell signaling proteins. Cancer Letters. 2008;269:199–225. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everett PC, Meyers JA, Makkinje A, Rabbi M, Lerner A. Preclinical Assessment of Curcumin as a Potential Therapy for B-CLL. American Journal of Hematology. 2007;82:23–30. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siwak DR, Shishodia S, Aggarwal BB, Kurzrock R. Curcumin-induced anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects in melanoma cells are associated with suppression of IκB kinase and nuclear factor κB activity and are independent of the B-raf/mitogen-activated/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase pathway and the Akt Pathway. Cancer. 2005;104:879–90. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Abbruzzese J, Kurzrock R. Nuclear factor-κB and IκB kinase are constitutively active in human pancreatic cells, and their down-regulation by curcumin (Diferuloylmethane) is associated with the suppression of proliferation and the induction of apoptosis. Cancer. 2004;101:2351–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Ahmed B, Mehta K, Kurzrock R. Liposomal curcumin with and without oxaliplatin: effects on cell growth, apoptosis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1276–82. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan TW, Tsai HR, Lu HF, et al. Curcumin-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human acute promyelocyctic leukemia HL-60 cells via MMP changes and caspase-3 activation. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:4361–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhillon N, Aggarwal BB, Newman RA, et al. Phase II trial of curcumin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4491–99. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang D, Veena MS, Stevenson K, et al. Liposome-encapsulated curcumin suppresses growth of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in vitro and in xenografts through the inhibition of NF-κB by an Akt-independent pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6228–36. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li L, Braiteh FS, Kurzrock R. Liposome-encapsulated curcumin: in vitro and in vivo effects on proliferation, apoptosis, signaling, and angiogenesis. Cancer. 2005;104:1322–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]