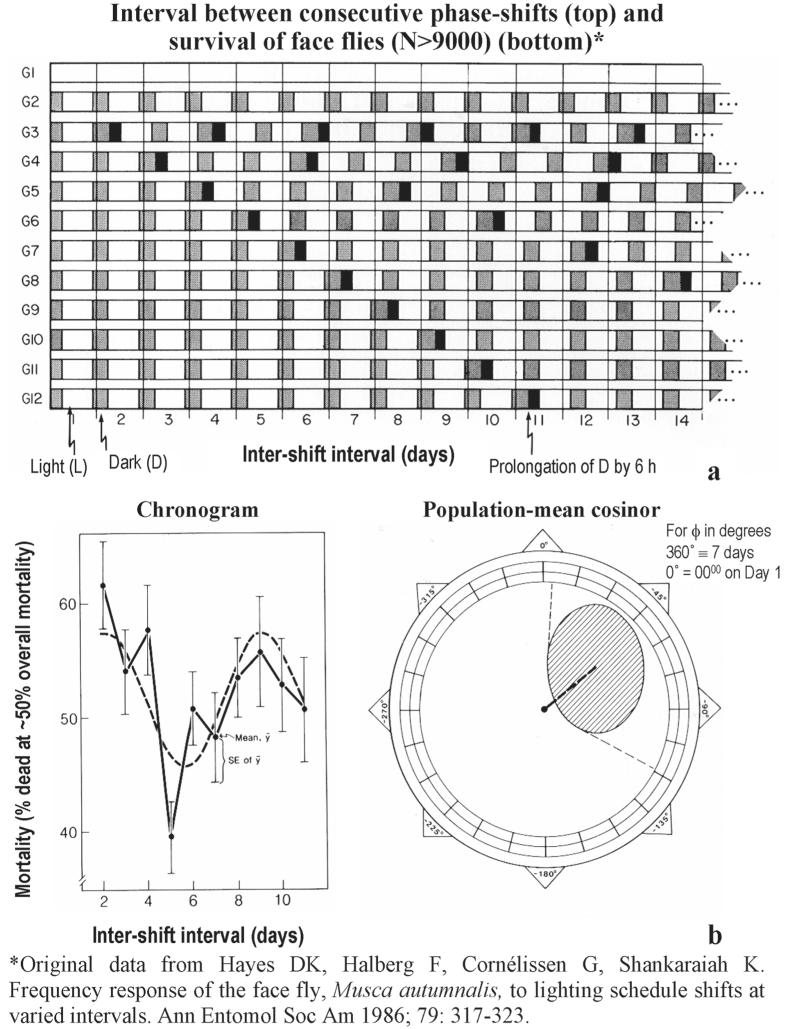

Figure 3.

With an experimental design shown on top, 29 experiments were carried out by Dr. Dora K. Hayes over 18 months on 7,835 adult face flies kept at 26 ± 1°C. When overall mortality reached about 50% in each separate experiment, groups of face flies subjected throughout a lifespan to shifts of a photoperiod of 16 hours of light alternating with 8 hours of darkness (as a 6-hour prolongation of the dark span) at varying intervals (every 2, 3, …, or 11 days) had different outcomes. Their summary is shown as means ± standard errors as a function of shift interval, to which a 7-day cosine curve is fitted by cosinor (bottom left). The extent of reproducibility (and the uncertainty) of the circaseptan response across the 29 experiments is illustrated by the statistically significant population-mean cosinor summary of the individual results (bottom right). The amplitude and phase of the response pattern are shown by the length and angle of a directed line (vector). Non-overlap of the center (pole) by the 95% confidence ellipse of the vector indicates that the zero-amplitude (no-rhythm) assumption is rejected, attesting to the statistical significance of the model. These results on face flies and those on springtails (Figure 4) and unicells (Figure 5) indicate that the role of the interval is structured by the stages of multi-frequency rhythms, rather than being better (or worse), depending linearly and solely upon the length of the inter-shift interval as a function only of the speed and phase relations of circadian rhythm-adjustments and hence on internal circadian phase relations, some of which may constitute circadian rhythm disruption (cf.1). © Halberg.