Abstract

Background

A biofilm is a complex community of microorganisms that develop on surfaces in diverse environments. The thickness of the biofilm plays a crucial role in the physiology of the immobilized bacteria. The most cariogenic bacteria, mutans streptococci, are common inhabitants of a dental biofilm community. In this study, DNA-microarray analysis was used to identify differentially expressed genes associated with the thickness of S. mutans biofilms.

Results

Comparative transcriptome analyses indicated that expression of 29 genes was differentially altered in 400- vs. 100-microns depth and 39 genes in 200- vs. 100-microns biofilms. Only 10 S. mutans genes showed differential expression in both 400- vs. 100-microns and 200- vs. 100-microns biofilms. All of these genes were upregulated.

As sucrose is a predominant factor in oral biofilm development, its influence was evaluated on selected genes expression in the various depths of biofilms. The presence of sucrose did not noticeably change the regulation of these genes in 400- vs. 100-microns and/or 200- vs. 100-microns biofilms tested by real-time RT-PCR.

Furthermore, we analyzed the expression profile of selected biofilm thickness associated genes in the luxS- mutant strain. The expression of those genes was not radically changed in the mutant strain compared to wild-type bacteria in planktonic condition. Only slight downregulation was recorded in SMU.2146c, SMU.574, SMU.609, and SMU.987 genes expression in luxS- bacteria in biofilm vs. planktonic environments.

Conclusion

These findings reveal genes associated with the thickness of biofilms of S. mutans. Expression of these genes is apparently not regulated directly by luxS and is not necessarily influenced by the presence of sucrose in the growth media.

Background

In nature, most microorganisms possess the ability to attach to solid surfaces and to develop a densely packed community – a biofilm [1]. In the biofilm ecological niche, bacteria exhibit increased resistance to antimicrobial compounds, environmental stresses and host immune defense mechanisms [2,3]. The environmental heterogeneity that develops in biofilms can accelerate phenotypic and genotypic diversity in bacterial populations that allows them to accomodate adverse ecological conditions within the biofilm. Oral biofilms harboring pathogenic bacteria are among the major virulent factors associated with dental diseases such as caries, gingivitis and periodontal diseases [4,5]. Streptococci, including mutans streptococci, are ubiquitous in the oral microbiota of humans. S. mutans is considered to be the most important etiological agent in dental caries. It forms biofilms on tooth surfaces and causes dissolution of enamel by acid end-products resulting from carbohydrate metabolism [6-8].

The dental biofilm is the net result of a community of bacteria cooperating to form well-differentiated structures with distinct thickness [9,10]. Cells in the biofilm have unique phenotypic characteristics, which are different from their planktonic counterparts [1,11], accompanied by significant changes in their patterns of gene expression [12,13]. Our previous, in vitro comparative transcriptome analysis confirmed the hypothesis that there are significant changes in the pattern of gene expression following the transition of bacteria to biofilm growth modes [14]. In this study, DNA-microarrays and real-time RT-PCR analysis were carried out to characterize the transcriptional differences of this bacterium in various biofilm depths.

Results and discussion

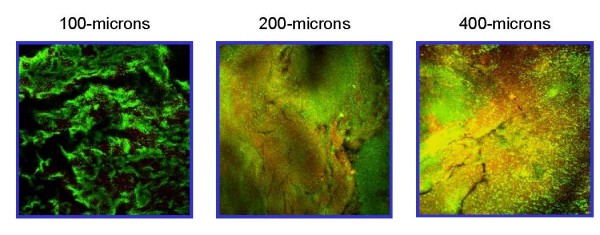

Viability and growth of bacteria within the biofilm is influenced by numerous environmental factors, such as nutrition supply, outflux of metabolites, pH gradient and oxygen tension [1,9,15]. Lack of nutrition and accumulation of toxic products may account for a decline in the growth of bacteria in suspension and in biofilm. One of the major rate-controlling factors in a biofilm ecosystem is the diffusion rate of nutrients in and waste products out and gases across the biofilm [9,15]. A thinner, or a low-density biofilm with void volumes and water channels may facilitate easier transport of nutrients in and waste products out across the biofilm, thus having a limited effect on bacterial proliferation [16,17]. It is conceivable therefore that the gene expression profile in thicker biofilms may be attributed to the effects of nutrient limitation to a large portion of the biomass due to diffusion restrictions. As biofilm thickness plays a paramount role, we conducted this study under controlled nutrient flow and controlled biofilm depth of 100, 200 and 400 microns, by using the constant-depth film fermenter (CDFF). The biofilms cultivated in the CDFF were assessed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). The CLSM images demonstrated that biofilm maturation and increased thickness is accompanied by significant alterations in cell viability in the different biofilm layers. According to our results, comparative vitality of bacteria grown at 100-micron depth was much greater than those cultured in CDFF at 200- or 400-microns depths (Fig. 1). This decrease in viability might be due to restriction in nutrient availability and accumulation of toxic metabolites as the biofilm thickens. Therefore it is reasonable that differential gene expression will allow the bacteria to acclimate in different ecological microenvironments.

Figure 1.

Live/dead staining of biofilms grown at different depths. S. mutans UA159 was grown at different biofilm depths in BHI, stained with LIVE/DEAD BacLight fluorescent dye and analyzed with CLSM. The panels show images of 100-microns, 200-microns and 400-microns depths biofilms cultivated in the CDFF. Dead cells are stained red, and live cells are stained green. The images are representative of three biological experiments.

Recent studies have revealed that the regulated death of bacterial cells is important for biofilm development. Following cell death, a subpopulation of the dead bacteria lyses and releases genomic DNA, which then has a central role in intercellular adhesion and biofilm stability [18]. Cell fate is generally thought of as being deterministic. That is, the fate that cells adopt is in most cases governed by the history of the cell or its proximity to inductive signals from other cells. However, an increasing number of cases are now known in which cell fate is controlled by stochastic (deterministic) mechanisms, for instance entry into the persister state in E. coli [19,20]. Stochastic fluctuations in the cellular components that determine cellular states can cause two distinct subpopulations, a property called bistability. Bistable switches produce polarized expression states and result in subpopulations of specialized cell types that are either ON or OFF for gene expression. Polarized output is thought to arise when a transcriptional regulator reaches a threshold activity and initiates an auto-regulatory positive feedback loop [21,22]. Below the threshold, the regulator does not auto-activate and the system remains in the OFF state. Above the threshold, runaway positive feedback results in activation of the system and stabilization of the ON state. Several properties in B. subtilis, the phenotypes of motility, genetic competence, sporulation and biofilm formation, are regulated by bistable gene expression [22-24]. It has been also demonstrated [24] that the genes encoding the components of the extracellular matrix in B. subtilis are expressed only in a subpopulation of cells. Matrix production is energetically costly and choosing the subset of cells within a given population to be responsible for producing and providing the extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) for the entire biofilm community might be especially economical. In the context of our results, the heterogeneity in the viable population of bacteria within the deep layers of a mature biofilm might be a result of a strategy to relegate the energetic cost to a subpopulation that would provide strengthening for the entire community. Phenotypic diversity within bacterial populations is advantageous. Multiple cell types permit a "division of labor", and cells with specialized properties may be primed to exploit or resist changes in the environment [21]. Consequently, biofilms should contain specialized cell types that are differentiated by transcriptional regulation, to express different phenotypic characteristics.

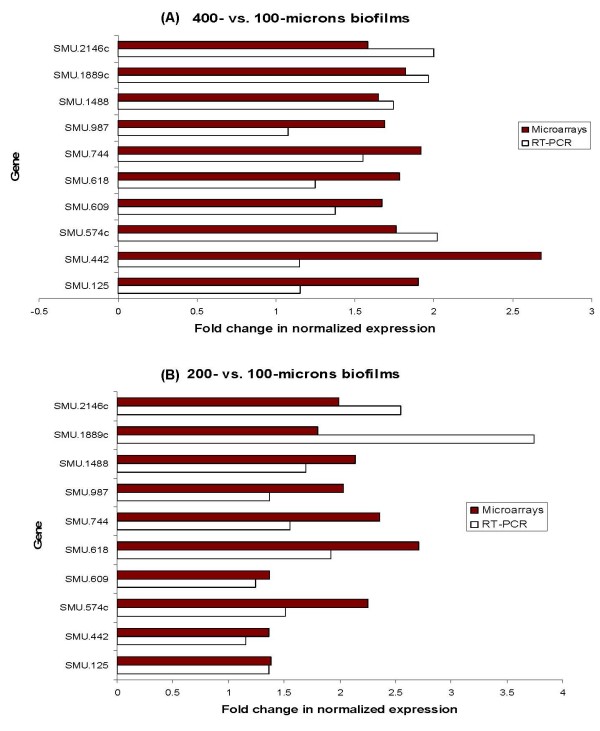

DNA-microarray analysis was used to identify differentially expressed genes associated with the thickness of S. mutans biofilm at various depths. Analyses of microarrays images, using an empirical Bayesian method (B-test) [25], indicated that expression of 29 genes was differentially changed in 400- vs. 100-microns depth biofilms (Table 1), and 39 genes in 200- vs. 100-microns depth biofilms (Table 2), at a confidence level of P ≤ 0.05 tested by moderated t-test. About 11% of these genes code for membrane-related proteins, while almost one-half of the differentially regulated genes code for hypothetical proteins of as yet unknown function present in the S. mutans genome. Only 10 genes of S. mutans (Table 3) showed differential expression in both 400- vs. 100-microns and 200- vs. 100-microns biofilms. All of these genes were upregulated. Verification of the microarrays data was carried out using real-time RT-PCR for expression analysis of selected differentially regulated genes (Fig. 2). A substantial number of them, such as SMU.574c, SMU.609, and SMU987, appeared to code for cell wall-associated proteins. SMU.987 encodes a cell wall-associated protein precursor WapA, a major surface protein [26], which modulates adherence and biofilm formation in S. mutans. Previous studies have demonstrated that levels of wapA in S. mutans were significantly increased in biofilm phase [27], whereas the inactivation of wapA resulted in reduction in cell aggregation and adhesion to smooth surfaces [28]. The wapA mutants are of reduced cell chain length, have less sticky cell surface, and unstructured biofilm architecture compared to the wild-type [29].

Table 1.

The most significant (P ≤ 0.05) differentially expressed genes of S. mutans in 400 μm vs. 100 μm biofilms

| Locus numbera | Descriptiona | Mb | P valuec | Bd |

| SMU.173 | putative ppGpp-regulated growth inhibitor | 1.021 | 0.001 | 5.781 |

| SMU.1710c | conserved hypothetical protein | 1.246 | 0.001 | 5.520 |

| SMU.991 | putative ribonucleotide reductase | 0.932 | 0.004 | 4.187 |

| SMU.1080c | conserved hypothetical protein possible transposon-related protein | -0.635 | 0.013 | 2.948 |

| SMU.564 | conserved hypothetical protein | 0.666 | 0.018 | 2.409 |

| SMU.1974 | putative pyrroline carboxylate reductase | 0.696 | 0.018 | 2.267 |

| SMU.1758c | conserved hypothetical protein | -0.666 | 0.028 | 1.676 |

| SMU.125 | conserved hypothetical protein | 0.914 | 0.028 | 1.564 |

| SMU.359 | translation elongation factor G (EF-G) | 0.978 | 0.028 | 1.477 |

| SMU.59 | adenylosuccinate lyase | 0.691 | 0.028 | 1.381 |

| SMU.987 | cell wall-associated protein precursor WapA | 0.760 | 0.028 | 1.313 |

| SMU.85 | putative phosphomethylpyrimidine kinase | 0.623 | 0.032 | 1.101 |

| SMU.2146c | hypothetical protein | 0.656 | 0.036 | 0.963 |

| SMU.37 | phosphoribosylaminoimidazolecarboxamide formyltransferase/IMP cyclohydrolase | 0.540 | 0.036 | 0.786 |

| SMU.02 | putative DNA polymerase III, beta subunit | 0.605 | 0.036 | 0.775 |

| SMU.609 | putative 40K cell wall protein precursor | 0.739 | 0.04 | 0.575 |

| SMU.574c | putative membrane protein | 0.814 | 0.04 | 0.487 |

| SMU.1353 | putative transposase | 0.461 | 0.04 | 0.485 |

| SMU.1839 | mannose-6-phosphate isomerase | 0.590 | 0.041 | 0.471 |

| SMU.641 | putative oxidoreductase | -0.595 | 0.044 | 0.225 |

| SMU.1889c | hypothetical protein | 0.860 | 0.044 | 0.213 |

| SMU.442 | conserved hypothetical protein | 1.416 | 0.044 | 0.171 |

| SMU.1646c | conserved hypothetical protein, possible hemolysis inducing protein | 1.031 | 0.044 | 0.157 |

| SMU.229 | conserved hypothetical protein | -0.480 | 0.045 | 0.096 |

| SMU.1760c | conserved hypothetical protein | -0.548 | 0.047 | 0.016 |

| SMU.84 | putative tRNA pseudouridine synthase A | 0.715 | 0.048 | -0.056 |

| SMU.2005 | putative adenylate kinase | -0.577 | 0.05 | -0.147 |

| SMU.1488c | conserved hypothetical protein | 0.725 | 0.05 | 0.033 |

| SMU.1642c | conserved hypothetical protein | 0.771 | 0.05 | -0.196 |

a Based on the genome annotation of S. mutans provided by TIGR.

b Log2-fold expression according to the M value, M > 0 means upregulation and M < 0 downregulation of the gene.

c Moderated t-test and its corresponding P value, adjusted by Benjamini and Yekutiely method.

d Bayesian test value, meaning the probability for a gene to be differentially expressed. Genes are listed according to their decreasing statistical importance according to their B-value.

Table 2.

The most significant (P < 0.05) differentially expressed genes of S. mutans in 200 μm vs. 100 μm biofilms

| Locus numbera | Descriptiona | Mb | P valuec | Bd |

| SMU.574c | putative membrane protein | 1.169 | 0.006 | 4.950 |

| SMU.1782 | conserved hypothetical protein | 1.250 | 0.016 | 2.504 |

| SMU.744 | putative cell division protein FtsY signal recognition | 1.236 | 0.016 | 2.545 |

| SMU.1889c | hypothetical protein | 0.850 | 0.016 | 2.536 |

| SMU.1537 | putative glycogen biosynthesis protein GlgD | 0.598 | 0.016 | 2.395 |

| SMU.1488c | conserved hypothetical protein | 1.103 | 0.018 | 2.187 |

| SMU.402 | pyruvate formate-lyase | 0.788 | 0.019 | 1.814 |

| SMU.943c | putative hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase | -0.617 | 0.019 | 1.780 |

| SMU.495 | glycerol dehydrogenase | 0.572 | 0.020 | 1.596 |

| SMU.804 | hypothetical protein | 0.940 | 0.025 | 1.234 |

| SMU.1578 | putative biotin operon repressor | 0.532 | 0.025 | 0.993 |

| SMU.814 | putative MutT-like protein | 0.598 | 0.025 | 0.984 |

| SMU.618 | hypothetical protein | 1.442 | 0.025 | 0.912 |

| SMU.987 | cell wall-associated protein precursor WapA | 1.020 | 0.025 | 0.881 |

| SMU.417 | conserved hypothetical protein | -0.622 | 0.025 | 0.866 |

| SMU.929c | conserved hypothetical protein | -0.562 | 0.028 | 0.776 |

| SMU.125 | conserved hypothetical protein | 0.457 | 0.032 | 0.518 |

| SMU.1841 | putative PTS system, sucrose-specific IIABC component | 0.782 | 0.038 | 0.300 |

| SMU.609 | putative 40K cell wall protein precursor | 0.454 | 0.042 | 0.144 |

| SMU.1626 | 50S ribosomal protein L1 | 0.897 | 0.042 | 0.401 |

| SMU.1298 | 50S ribosomal protein L31 | -0.692 | 0.042 | 0.081 |

| SMU.630 | hypothetical protein | -0.483 | 0.042 | 0.036 |

| SMU.892 | putative type I restriction-modification system, specificity determinant | -0.745 | 0.043 | 0.067 |

| SMU.2105 | hypothetical protein | 0.862 | 0.043 | -0.127 |

| SMU.2146c | hypothetical protein | 0.993 | 0.043 | -0.146 |

| SMU.1975c | conserved hypothetical protein possible membrane protein | 0.900 | 0.043 | 0.182 |

| SMU.102 | putative PTS system, IID component | -0.422 | 0.045 | -0.218 |

| SMU.149 | putative transposase | 0.795 | 0.046 | -0.285 |

| SMU.883 | dextran glucosidase DexB | 0.393 | 0.046 | -0.322 |

| SMU.99 | fructose-1,6-biphosphate aldolase | 0.510 | 0.046 | -0.331 |

| SMU.27 | putative acyl carrier protein AcpP | 0.809 | 0.047 | -0.059 |

| SMU.91 | peptidyl-prolyl isomerase RopA (trigger factor) | 0.544 | 0.049 | -0.525 |

| SMU.1421 | putative dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase, E2 component | 0.565 | 0.049 | -0.564 |

| SMU.886 | galactokinase, GalK | 0.676 | 0.049 | -0.577 |

| SMU.753 | conserved hypothetical protein | -0.700 | 0.049 | -0.592 |

| SMU.442 | conserved hypothetical protein | 0.435 | 0.049 | -0.600 |

| SMU.1854 | conserved hypothetical protein | -0.748 | 0.049 | -0.229 |

| SMU.940c | putative hemolysin III | -0.651 | 0.049 | -0.473 |

a Based on the genome annotation of S. mutans provided by TIGR.

b Log2-fold expression according to the M value, M > 0 means upregulation and M < 0 downregulation of the gene.

c Moderated t-test and its corresponding P value, adjusted by Benjamini and Yekutiely method.

d Bayesian test value, meaning the probability for a gene to be differentially expressed. Genes are listed according to their decreasing statistical importance according to their B-value.

Table 3.

Nucleotide sequences of primers for genes whose expression in both 400 μm vs. 100 μm and 200 μm vs. 100 μm biofilms was compared

| ORFa | Primer Sequences (5' – 3') | |

| Forward | Reverse | |

| 16S rRNA | CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTAG | CAACAGAGCTTTACGATCCGAAA |

| SMU.125 | TGGCACATGCACGAGAAGAA | GGCCCGGAATAGCATAGTTG |

| SMU.442 | CTTTCAGGCGGGATGTTGAG | GCTGTCTGGCGGTTTCAATC |

| SMU.574c | TGGTCATACAGTTGTGCAGC | GACGAGGCCGATGCAACA |

| SMU.609 | CAGTTGTGAACGTGGCTGAAA | TGAGCTGCTGCCTTATCTGAAA |

| SMU.618 | GCACTTATCGCTTGCGGTTT | CACCTGACAATACCAGCAACCA |

| SMU.744 | TGTTCAGGTTGCGTCAACCTT | AATGACACGGCGAAGAGCTT |

| SMU.987 | GCACGCTTGCAGTACATTGC | CATAAGGTCGCGAGCAGCT |

| SMU.1488c | ACGCCATCTCATCAGCCTTT | ACCACTTACCCAATCGCTTGA |

| SMU.1889c | CTGCTGTATCTGCCCCTGCT | CCTAAATCCCAACCAATTGCTG |

| SMU.2146c | CAGGAGCTTCAGGTCTCTTTCAAA | CCTTGGGCTTTATAAGCATTGATAG |

a Based on the genome annotation of S. mutans provided by TIGR

Figure 2.

Comparison of microarrays and RT-PCR expression data. Comparison of microarrays and RT-PCR expression values for selected genes of S. mutans, grown in different biofilm depths in CDFF. The data are expressed as the means of at least two biologically independent experiments.

SMU.744, encoding membrane-associated receptor protein FtsY, the third universally conserved element of the signal recognition particle (SRP) translocation pathway [30], was also found among these differentially expressed genes. SRP was first identified in mammalian cells, and later in bacteria, and it was further shown that components of the SRP pathway are universally conserved in all three domains of life – archaea, bacteria, and eukaryote domains [31]. The SRP pathway delivers membrane and secretory proteins to the cytoplasmic membrane or endoplasmic reticulum [32]. S. mutans remained viable but physiologically impaired and sensitive to environmental stress when ftsY and other genes of the SRP elements were inactivated [30]. The upregulation of FtsY in the deep layers of the biofilm indicates that the SRP system is crucial for bacterial survival in highly condensed mature biofilm.

Interestingly, relatively few of the differentially expressed genes showed more than a 2-fold change. However, even small changes in mRNA levels could have the biological potential to affect bacterial metabolism and physiology. Relatively small changes in the level of expression of one gene can be amplified through regulatory networks and result in significant phenotypic alteration [33]. Many genes among those upregulated in 200- vs. 100-microns biofilms are involved in energy metabolism, including SMU.99, SMU.402, SMU.883, SMU.886 and SMU.1537. However, a substantial number – 11% of the upregulated genes – code for cell wall-associated proteins, such as SMU.574c and SMU.609. Several differentially expressed genes in the 400- vs. 100-microns depths are presumably regulatory genes, e.g. SMU.173 and SMU.359, which influence biofilm formation.

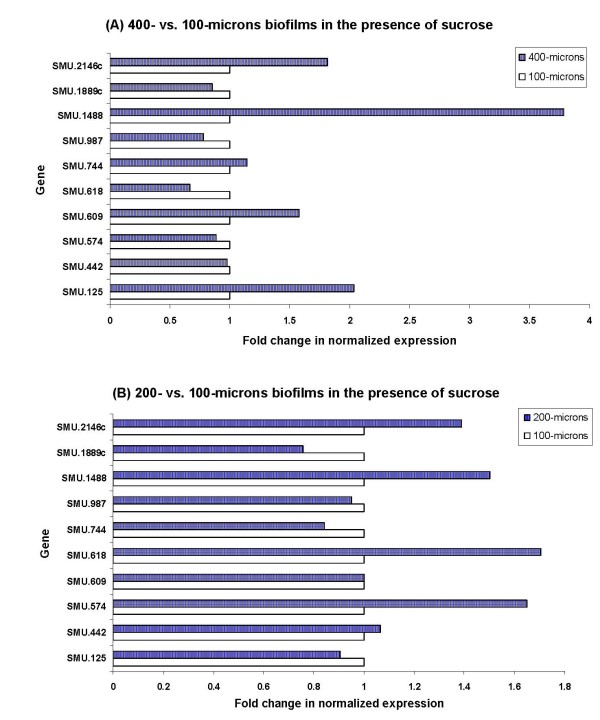

Previous studies have shown that carbohydrates have a major influence on biofilm-associated gene expression of several types of bacteria [34-37]. Sucrose-dependent adhesion is a major mechanism of biofilm formation and maturation in dental biofilms [34-37]. In order to evaluate whether sucrose influences the expression of selected genes of S. mutans, we generated biofilms of 100-, 200- and 400-micron depths in the presence of 2% sucrose. It is of interest that the presence of sucrose did not dramatically change the regulation of the selected genes in 400- vs. 100-microns (Fig. 3A) or 200- vs. 100-microns biofilms (Fig. 3B) tested by real-time RT-PCR. Only SMU.1488 of the tested genes showed significant upregulation in 400- vs. 100-microns depth of biofilm with sucrose (Fig. 3A). A possible explanation of these results could be that sucrose affects mostly the initial stages of biofilm formation, as generation of the sticky glucans and fructans is especially crucial in the initial stages of adhesion [6,34], while the biofilm thickness-associated genes are activated mostly in the late steps of biofilm development. The genes, which appear to be responsible for biofilm thickness and maturation processes, are not necessarily influenced by the presence of sucrose during the initial biofilm formation stage.

Figure 3.

Gene expression of S. mutans in the presence of sucrose. Gene expression of S. mutans grown at various biofilm depths in the presence of 2% sucrose. The data are expressed as the means of at least two biologically independent experiments.

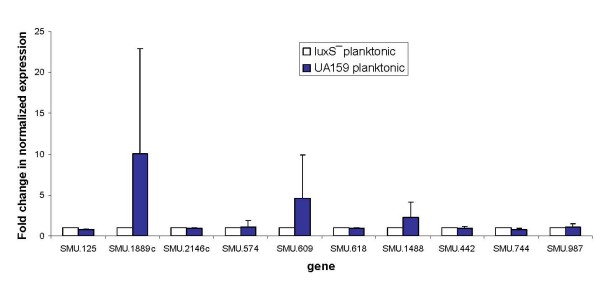

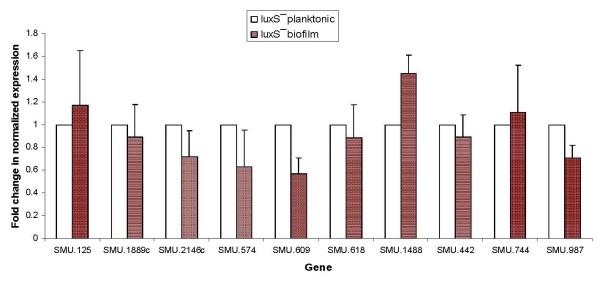

Cell-cell communication plays an important role in the successful formation, survival and virulence of the biofilm community [38-41]. Gram-positive bacteria generally communicate via small diffusible peptides [40,42], while many Gram-negative bacteria secrete acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs) [42,43], the structure of which varies depending on the species of bacteria that produce them. Another system associated with quorum sensing (QS) involves the synthesis of autoinducer-2 (AI-2), which is derived from a common precursor, 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentadione (DPD), the product of the LuxS enzyme [44,45]. This system may be involved in cross-communication among both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as homologues of LuxS are widespread within the microbial world. LuxS is highly conserved in the bacterial kingdom [46-50]. In S. mutans, QS regulates cardinal physiological functions, such as the ability to withstand environmental stress conditions, competence and biofilm formation [51,52]. Knockout of the luxS gene was shown to impair biofilm growth and stress tolerance of bacteria [46,52,53]. As a step towards understanding the possible link between biofilm thickness and QS, we analyzed the profile of selected gene expression in a luxS- mutant strain. The expression of genes identified in this study as associated with biofilm thickness was first compared between the mutant and wild-type strains in planktonic condition, and afterwards under biofilm vs. planktonic environments in the luxS- strain. Interestingly, there were no radical changes in expression of genes associated with biofilm thickness in the tested conditions (Fig. 4). Only minor downregulation was recorded in SMU.2146c, SMU.574, SMU.609, and SMU.987 genes expression in biofilm vs. planktonic conditions (Fig. 5). This result may explain the observation that biofilms of S. mutans deficient in luxS were not radically different from the wild-type [54]. Although luxS plays an important role in initial adherence and initiation of mature biofilm development, it seems that biofilm thickness-associated genes are not regulated directly by luxS in S. mutans UA159. Interestingly, the luxS- mutant showed a diminished capacity to form biofilm when sucrose was provided as a supplemental sugar [52], so it can be suggested that luxS plays a significant role, most likely in regulation of sucrose-dependent adherence rather than cell-cell interactions during biofilm growth in S. mutans.

Figure 4.

Regulation of S. mutans genes expression. Regulation of selected gene expression of S. mutans UA159 compared with the luxS- strain in planktonic growth examined by real-time RT-PCR. The data are expressed as the means and standard deviations of at least two biologically independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Regulation of S. mutans gene expression. Regulation of selected gene expression of S. mutans luxS- examined by real-time RT-PCR in biofilm compared with planktonic cultures. The data are expressed as the means and standard deviations of at least two biologically independent experiments.

Conclusion

This study provides a genome-scale outline of genes associated with biofilm thickness in S. mutans, a highly pathogenic bacterium in dental diseases. By expression alterations in these genes, the bacteria within the various layers of a mature biofilm may express different phenotypic characteristics allowing better acclimation in the biofilm micro-environment. Moreover, the expression of these genes is not directly regulated by luxS and is not necessarily influenced by the presence of sucrose during biofilm maturation.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

S. mutans UA159 and its derivative mutant strain luxS- [54] were incubated in Brain Heart Infusion Broth (BHI, Difco Labs, Detroit, USA) at 37°C in 95% air/5% CO2 (v/v), with the addition of erythromycin (10 μg/ml) in the case of the luxS- strain. Cultures of S. mutans were diluted 1:50, inoculated into fresh BHI media and grown in polystyrene tubes for 24 h (37°C, 95% air/5% CO2 (v/v)) for planktonic culture generation. The biofilm of luxS- was grown in BHI with addition of erythromycin (10 μg/ml) in 20-mm diameter, 15-mm deep sterile polystyrene multidishes (NUNCLON-143982, Roskilde, Denmark), as described previously [14].

As biofilm thickness plays a crucial role in mature biofilm development, we generated biofilms of wild-type bacteria under controlled nutrition flow and controlled biofilm depth conditions, by using the constant depth film fermentor (CDFF) [55]. The rotating turntable in the CDFF contained 15 polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) pans, rotated under PTFE scraper bars that smear the incoming medium over the 15 pans. Each sampling pan contained 5 cylindrical holes (5.0 mm in diameter) with PTFE plugs on which biofilms were formed. The desired depth of biofilm was achieved using a recessing tool, which pushes the plug down to the required depth (100, 200 or 400 μm).

The biofilms were grown for 72 h at different biofilm depths of 100, 200 and 400 microns, as follows: pure cultures of S. mutans UA159 were cultivated overnight at 37°C in 700 ml of BHI. Next, the inoculum was pumped into the CDFF for 7 h via a peristaltic pump (ISMATEC SA, Labortechnik-Analytik, Zurich, Switzerland) at a rate of 100 ml/h at 37°C. BHI was delivered into the CDFF at a rate of 100 ml/h. After 72 h at 37°C, the PTFE cylindrical plugs, on which the biofilms of different depths were grown, were carefully removed from the CDFF. The collected biofilms were washed gently with sterile PBS, and the biofilm bacteria were harvested and subjected to RNA extraction. We also tested whether the addition of sucrose to the growth medium had any influence on the expression of the selected genes (Table 3) of S. mutans biofilms grown to 100-, 200- and 400-microns depths; the biofilm samples were generated and grown for 72 h in CDFF with unsupplemented BHI, and BHI supplemented with 2% sucrose (Frutarom Ltd, Israel).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

The biofilm samples developed on plugs which were not used for the gene expression analysis were stained with LIVE/DEAD BacLight fluorescent dye (Molecular Probes, OR) (1:100) for 10 min. Dead bacteria are stained red while the live ones are stained green. Fluorescent images of the PBS washed samples were assessed using a Zeiss LSM 410 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany) confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM), equipped with PlonNeofluor × 10 lens (Zeiss). In each experiment, exciting laser intensity, background level, contrast and electronic zoom size were maintained at the same level. At least three random fields were analyzed in each experiment. A series of optical cross-sectional images were acquired from the surface through the vertical axis of the specimen, using a computer-controlled motor drive. 3-D confocal images were reconstituted with Image Pro Plus 4.2 (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) and processed for display using Adobe Photoshop Ver 7.0 software. The thickness of the biofilm was controlled and determined by the CDFF apparatus; estimation of live/dead ratio was assessed according to the CLSM. Due to limitations of the CLSM technique, the 400-microns depth biofilm calculation does not necessarily include the entire biofilm depth [56].

RNA extraction

Extraction of total RNA from bacteria grown in biofilms as well as planktonically grown cells was performed as described previously [14]. The RNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using the Nanodrop Instrument (ND-1000, Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). The integrity of the RNA was examined by agarose-gel electrophoresis (data not shown).

Microarrays design, cDNA labeling and hybridization

The arrays consisted of 1948 70-mer oligonucleotides representing 1960 open reading frames (ORF) from S. mutans UA159 and additional control sequences. The probe labeling, hybridization and array data normalization were carried out as previously described [14]. In brief, cDNA was generated with random primers from total RNA and labeled indirectly with cy3 or cy5 dyes. The hybridizations were all performed against the 100-micron biofilm in a reference design manner. The slides were scanned using a Genepix 4000B scanner (Axon Ltd). Fluorescence intensities were quantitatively analyzed using GenePix Pro 4.1 software (Axon). The result files (gpr) produced by GenePix were analyzed utilizing the LIMMA software package [57], available from the CRAN site http://www.r-project.org. After filtering, the data within the same slide were normalized using global loess normalization with a default smoothing span of 0.3 [58]. To identify differentially expressed genes, a parametric empirical Bayes approach implemented in LIMMA was used [25]. According to this approach, data from all the genes in a replicate set of experiments are combined into estimates of parameters of a priori distribution. These parameter estimates are then combined at the gene level with means and standard deviations to form a statistic B that is a Bayes log posterior odds [25]. B can then be used to determine whether differential expression has occurred. A moderated t-test was performed in parallel, with the use of a false discovery rate correction for multiple testing [59]. TIGR arrays include four replicates for each gene. Instead of just taking the average of replicate spots, we used the duplicate correlation function [60] available in LIMMA to acquire an approximation of gene-by-gene variance. This method greatly improves the precision with which the gene-wise variances are estimated and thereby maximizes inference methods designed to identify differentially expressed genes. A P value < 0.05 confidence level was used to pinpoint the significantly differentiated genes. Genes had to have an A-value (A = log2 [Cy3 × Cy5]/2), the average expression level for the gene across all arrays and channels) of more than 8.5, leaving out genes with an average intensity in both channels less than 256. The microarray data were deposited in the GEO public repositories with accession number GSE12496.

Reverse transcription and real-time quantitative PCR

Quantitative SYBR green PCR assays employing an ABI-Prism 7300 Light Cycler System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) were performed as described previously [36]. The corresponding oligonucleotide primers were designed using the algorithms provided by Primer Express (Applied Biosystems) for uniformity in size (≈ 90 base-pairs) and melting temperature. For each set of primers, a standard amplification curve was plotted (critical threshold cycle against log of concentration), and only those with slope ≈ -3 were considered reliable primers. The expression levels of all the tested genes for real-time RT-PCR were normalized using the 16S rRNA gene of S. mutans (Acc. No. X58303) as an internal standard. Each assay was performed with at least two independent RNA samples in duplicate.

Abbreviations

AHL: acyl homoserine lactone; AI-2: autoinducer-2; BHI: brain heart infusion; CDFF: constant-depth film fermenter; CLSM: confocal laser scanning microscope; EPS: extracellular polysaccharides; QS: quorum sensing; PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene; RT-PCR: reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; TIGR: The Institute for Genomic Research.

Authors' contributions

MS planed and carried out the experiments, performed the array and real time RT-PCR analyses and wrote the original manuscript. AT assisted in biofilms generation, RNA extraction, RT-PCR and CLSM experiments. MK performed the probe labeling, hybridization and array data normalization for DNA-microarrays. MF helped in setting up and performing the CDFF experiments to generate different depths of biofilm. DS conceived the study and oversaw its execution; he also revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. MS and DS integrated all of the data throughout the study and crafted the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Microarrays were provided by the NIDCR through the PFGRC at TIGR. We thank Dr. Robert Burne for kindly providing the S. mutans luxS- strain. This study contains part of the Ph.D. dissertation of Moshe Shemesh.

Contributor Information

Moshe Shemesh, Email: moshe.shemesh@mail.huji.ac.il.

Avshalom Tam, Email: avshalomt@gmail.com.

Miriam Kott-Gutkowski, Email: miriamk@ekmd.huji.ac.il.

Mark Feldman, Email: markfel15@yahoo.com.

Doron Steinberg, Email: dorons@cc.huji.ac.il.

References

- Marsh PD. Dental plaque: biological significance of a biofilm and community life-style. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart PS, Costerton JW. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms. Lancet. 2001;358:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh PD. Are dental diseases examples of ecological catastrophes? Microbiology. 2003;149:279–294. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. Bacterial biofilms and human disease. Sci Prog. 2001;84:235–254. doi: 10.3184/003685001783238998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramitsu HK. Virulence factors of mutans streptococci: role of molecular genetics. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:159–176. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WH. Do we need to be concerned about dental caries in the coming millennium? Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:126–131. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljemark WF, Bloomquist C. Human oral microbial ecology and dental caries and periodontal diseases. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1996;7:180–198. doi: 10.1177/10454411960070020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg D. Studying plaque biofilms on various dental surfaces. In: An YH, Friedman RJ, editor. Handbook of Bacterial Adhesion: Principles, Methods, and Applications. Totowa: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 353–370. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Cate JM. Biofilms, a new approach to the microbiology of dental plaque. Odontology. 2006;94:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10266-006-0063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore KS, Srinivas P, Akins DR, Hatter KL, Gilmore MS. Growth, development, and gene expression in a persistent Streptococcus gordonii biofilm. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4759–4766. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4759-4766.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer K, Camper AK, Ehrlich GD, Costerton JW, Davies DG. Pseudomonas aeruginosa displays multiple phenotypes during development as a biofilm. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1140–1154. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.1140-1154.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley M, Bangera MG, Bumgarner RE, Parsek MR, Teitzel GM, Lory S, Greenberg EP. Gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature. 2001;413:860–864. doi: 10.1038/35101627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemesh M, Tam A, Steinberg D. Differential gene expression profiling of Streptococcus mutans cultured under biofilm and planktonic conditions. Microbiology. 2007;153:1307–1317. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/002030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden GH, Li YH. Nutritional influences on biofilm development. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:81–99. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110012101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden GH, Hamilton IR. Survival of oral bacteria. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:54–85. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen R, Bachrach G, Bronshteyn M, Gedalia I, Steinberg D. The role of fructans on dental biofilm formation by Streptococcus sobrinus, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus gordonii and Actinomyces viscosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;195:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayles KW. The biological role of death and lysis in biofilm development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:721–726. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban NQ, Merrin J, Chait R, Kowalik L, Leibler S. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science. 2004;305:1622–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1099390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:48–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DB. Division of labour during Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:229–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DB, Losick R. Cell population heterogeneity during growth of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:3083–3094. doi: 10.1101/gad.1373905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubnau D, Losick R. Bistability in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:564–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Chu F, Kolter R, Losick R. Bistability and biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:254–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonnstedt I, Speed T. Replicated microarray data. Statistica Sinica. 2002;12:31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Russell MW, Harrington DJ, Russell RR. Identity of Streptococcus mutans surface protein antigen III and wall-associated protein antigen A. Infect Immun. 1995;63:733–735. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.733-735.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque CM, Voronejskaia E, Huang YC, Mair RW, Ellen RP, Cvitkovitch DG. Involvement of sortase anchoring of cell wall proteins in biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3773–3777. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3773-3777.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H, Dao ML. Inactivation of the Streptococcus mutans wall-associated protein A gene (wapA) results in a decrease in sucrose-dependent adherence and aggregation. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5021–5028. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5021-5028.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Kreth J, Cross SE, Gimzewski JK, Shi W, Qi F. Functional characterization of cell-wall-associated protein WapA in Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology. 2006;152:2395–2404. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28883-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasona A, Crowley PJ, Levesque CM, Mair RW, Cvitkovitch DG, Bleiweis AS, Brady LJ. Streptococcal viability and diminished stress tolerance in mutants lacking the signal recognition particle pathway or YidC2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17466–17471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508778102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan RJ, Freymann DM, Stroud RM, Walter P. The signal recognition particle. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:755–775. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskovits AA, Bochkareva ES, Bibi E. New prospects in studying the bacterial signal recognition particle pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:927–939. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionato MR, Tucker CM, Kuboniwa M, Lamont G, Demuth DR, Tribble GD, Lamont RJ. Porphyromonas gingivalis genes involved in community development with Streptococcus gordonii. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6419–6428. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00639-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burne RA, Chen YY, Penders JE. Analysis of gene expression in Streptococcus mutans in biofilms in vitro. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:100–109. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110010101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemesh M, Tam A, Steinberg D. Expression of biofilm-associated genes of Streptococcus mutans in response to glucose and sucrose. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:1528–1535. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemesh M, Tam A, Feldman M, Steinberg D. Differential expression profiles of Streptococcus mutans ftf, gtf and vicR genes in the presence of dietary carbohydrates at early and late exponential growth phases. Carbohydr Res. 2006;341:2090–2097. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Kuramitsu HK. A pleiotropic regulator, Frp, affects exopolysaccharide synthesis, biofilm formation, and competence development in Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4581–4589. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00001-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolenbrander PE. Oral microbial communities: biofilms, interactions, and genetic systems. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:413–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolenbrander PE, Andersen RN, Blehert DS, Egland PG, Foster JS, Palmer RJ., Jr Communication among oral bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:486–505. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.486-505.2002. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie KR, Heurlier K. Establishing bacterial communities by 'word of mouth': LuxS and autoinducer 2 in biofilm development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:635–643. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Tribble GD, Tucker CM, Anaya C, Shizukuishi S, Lewis JP, Demuth DR, Lamont RJ. A Porphyromonas gingivalis Tyrosine Phosphatase is a Multifunctional Regulator of Virulence Attributes. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:1153–1164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C, Greenberg EP. Listening in on bacteria: acyl-homoserine lactone signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:685–695. doi: 10.1038/nrm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead NA, Barnard AM, Slater H, Simpson NJ, Salmond GP. Quorum-sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2001;25:365–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federle MJ, Bassler BL. Interspecies communication in bacteria. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1291–1299. doi: 10.1172/JCI20195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzer K, Hardie KR, Williams P. LuxS and autoinducer-2: their contribution to quorum sensing and metabolism in bacteria. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2003;53:291–396. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(03)53009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt J, Kreth J, Shi W, Qi F. LuxS controls bacteriocin production in Streptococcus mutans through a novel regulatory component. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:960–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson KK. What drives bacteria to produce a biofilm? FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;236:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler BL, Losick R. Bacterially speaking. Cell. 2006;125:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke JM, Bassler BL. Three parallel quorum-sensing systems regulate gene expression in Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6902–6914. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6902-6914.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela S, Frank S, Belausov E, Pinto R. A Mutation in the luxS gene influences Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5653–5658. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00048-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos JA, Brown TA, Jr, Burne RA. Effects of RelA on key virulence properties of planktonic and biofilm populations of Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1431–1440. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1431-1440.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZT, Burne RA. LuxS-mediated signaling in Streptococcus mutans is involved in regulation of acid and oxidative stress tolerance and biofilm formation. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2682–2691. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2682-2691.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Ansai T, Takehara T, Kuramitsu HK. LuxS-based signaling affects Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:2372–2380. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.5.2372-2380.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZT, Burne RA. Functional genomics approach to identifying genes required for biofilm development by Streptococcus mutans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:1196–1203. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.3.1196-1203.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratten J, Wilson M. Antimicrobial susceptibility and composition of microcosm dental plaques supplemented with sucrose. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1595–1599. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paramonova E, de Jong ED, Krom BP, Mei HC van der, Busscher HJ, Sharma PK. Low-load compression testing: a novel way of measuring biofilm thickness. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:7023–7028. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00935-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:Article3. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK, Speed T. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods. 2003;31:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Yekutieli D, Benjamini Y. Identifying differentially expressed genes using false discovery rate controlling procedures. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:368–375. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btf877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK, Michaud J, Scott HS. Use of within-array replicate spots for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2067–2075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]