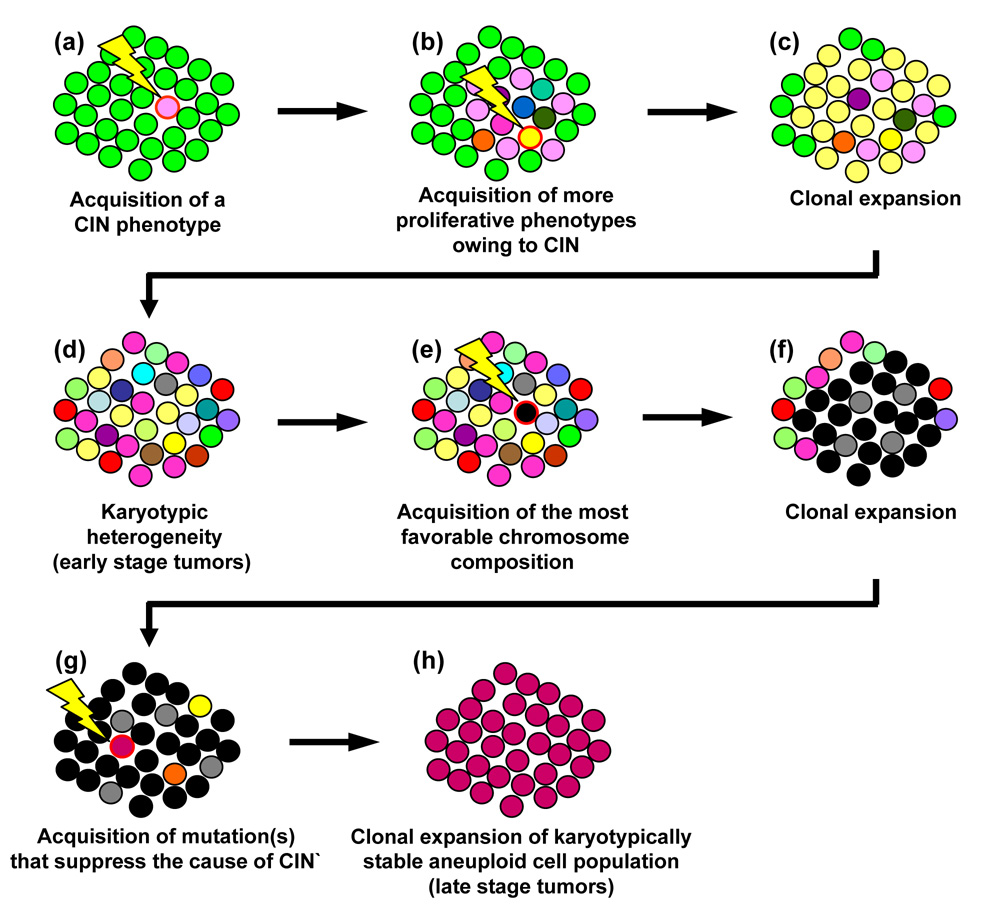

Figure 4. Karyotypic convergence during tumor progression.

The early stage tumors are often karyotypically heterogeneous, while the late stage tumors are karyotypically homogenous. The karyotypic convergence theory provides the mechanism underlying this phenomenon. A cell acquires a mutation that renders growth advantage over the others, and clonally expands (a). Among this particular population of cells, one or a few cells acquire the mutations that destabilize chromosomes (CIN phenotype, i.e., centrosome amplification) (b). Because of the CIN phenotype, the population gradually becomes karyotypically heterogeneous (c), representing the early stage tumor. A cell within this population eventually acquires the favorable chromosome composition that renders maximal growth/carcinogenic potentials (d), and clonally expands (f). For these cells, maintenance of this particular chromosome composition becomes the priority, selecting the cell(s) that have acquired the mutation(s) that either counteract or eliminate the cause of CIN (g). Such a cell will eventually dominate the population by retaining the favorable karyotypic composition, and thus the population becomes karyotypically homogenous, representing late stage tumors.