Abstract

Although much is known about classic IFNγ inducers, little is known about the IFNγ inducing capability of inflammasome-activated monocytes. In this study, supernatants from LPS/ATP-stimulated human monocytes were analyzed for their ability to induce IFNγ production by KG-1 cells. Unexpectedly, monocyte-derived IFNγ inducing activity was detected, but it was completely inhibited by IL-1β, not IL-18 blockade. Moreover, size-fractionation of the monocyte conditioned media dramatically reduced the IFNγ inducing activity of IL-1β, suggesting that IL-1β requires a cofactor to induce IFNγ production in KG-1 cells. Because TNFα is known to synergize with IL-1β for various gene products, it was studied as the putative IL-1β synergizing factor. Although recombinant TNFα (rTNFα) alone had no IFNγ inducing activity, neutralization of TNFα in the monocyte conditioned media inhibited the IFNγ inducing activity. Furthermore, rTNFα restored the IFNγ inducing activity of the size-fractionated IL-1β. Finally, rTNFα synergized with rIL-1β, as well as with rIL-1α and rIL-18, for KG-1 IFNγ release. These studies demonstrate a synergistic role between TNFα and IL-1 family members in the induction of IFNγ production and give caution to interpretations of KG-1 functional assays designed to detect functional IL-18.

Keywords: Interleukin-1, caspase-1, TNFα, KG-1 cell line, IFNγ

1. Introduction

Toll-like receptor mediated pathogen recognition by monocytes/macrophages leads to immediate NFκB activation and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-8, and IL-1β [1–6]. Interleukin-1β and IL-18 belong to the IL-1 family and are both synthesized by monocytic cells as biologically inactive precursors that undergo caspase-1-mediated proteolytic cleavage into biologically active forms [7–11]. However, unlike IL-1β, IL-18 is constitutively expressed at the mRNA and protein level. Caspase-1 activation depends upon assembly of a multi-protein complex known as the inflammasome, which is classically induced upon recognition of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as LPS, followed by a brief pulse with ATP [12–14].

Interleukin-18 is mainly known for its IFNγ inducing capability, especially in synergy with IL-12 [15–20]. Although IFNγ is characteristically produced by NK, T and NKT cells, cells of the monocytic lineage have also been shown to constitutively and inducibly express IFNγ [21–27]. The human acute myeloid leukemic KG-1 cell line has been typically used in biological assays to assess the IFNγ inducing activity of IL-18 [28,29]. Specifically, the KG-1 bioassay has been used to study the IL-18 neutralizing capabilities of IL-18 antibodies [30–32] and human/virus-derived IL-18 binding proteins (IL-18 BP) [32–39], to study receptor-associated events [35,38,40,41] and signaling pathways [34,35,42,43] leading to IFNγ gene expression, and to measure the activity of endogenous IL-18 in biological samples [29,44]. Interestingly, IL-12 alone does not induce IFNγ production by KG-1 cells [29], and our preliminary experiments indicated that IL-12 does not synergize with IL-18 for IFNγ production in KG-1 cells.

The expression of many IL-1β-induced inflammatory genes is synergistically enhanced by the LPS-induced cytokine, TNFα [9,45–49]. However, IL-1β is not well-known for its IFNγ inducing capability. Only a few reports have implicated IL-1β in IFNγ production in synergy with IL-2 or IL-12 in NK and T cells [18,50–55]. Moreover, KG-1 cells do not release significant amounts IFNγ in response to rIL-1β (Fig. 1) and are typically used in bioassays to detect the activity of IL-18, not IL-1β or IL-12 [28–44].

Figure 1. KG-1 cells release IFNγ in response to rIL-18, not rIL-1β.

KG-1 cells (106/ml) were incubated with rIL-18, rIL-1β, or both (6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 ng/ml each). KG-1 supernatants were harvested after 24 h of stimulation and analyzed for IFNγ release by ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3–20)

In this report, we examined the ability of inflammasome-activated monocytes to induce IFNγ production by KG-1 cells. Importantly, we found a monocyte-derived, caspase-1 dependent, IFNγ inducing factor that was released within 4 h of LPS/ATP stimulation. Although LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes released IL-18, this cytokine was not responsible for the detected IFNγ inducing activity. Via neutralization, immunodepletion and size-fractionation experiments we discovered that the detected IFNγ inducing activity was synergistically mediated by IL-1β and TNFα, and that neither one of these cytokines alone possess IFNγ inducing activity in KG-1 cells. Finally, we found that rTNFα synergized not only with rIL-1β, but also with rIL-18 and rIL-1α for IFNγ production. The lack of IL-18-mediated IFNγ inducing activity in the monocyte conditioned media was likely due to sub-optimal levels of released IL-18, or to IL-18 being bound to an inhibitory protein. These findings suggest that common signaling pathways downstream of members of the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) family may be crucial for the observed synergy with TNFα. Moreover, our results are unique in light of the facts that, IL-1β and IL-1α are not commonly known as an IFNγ inducing factors, and IL-1 cytokines and TNFα have never been shown to synergize for IFNγ production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Purified Escherichia coli (E. coli) LPS (serotype 0111:B4) was obtained from Axxora (San Diego, CA) and cell culture tested adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) disodium salt from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Anti-human IL-1β, IL-18 and IL-8 ELISA capture monoclonal Abs (clones 2805, 125-2H and 6217), IL-18 detection monoclonal Ab (clone 159-12B), IL-18 receptor (IL-18R) monoclonal Ab (clone 70625), IL-18 binding protein (IL-18BP), and human recombinant IL-1β (rIL-1β), rIL-18, rIL-1α, rIL-8 and rIL-12 were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). A TNFα capture monoclonal Ab (clone 2C8) was obtained from Advanced Immunochemical (Long Beach, CA), an IL-8 detection polyclonal Ab from Endogen (Rockford, IL), and an IL-12 neutralizing Ab (clone C8.6) and IFNγ ELISA kit from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Recombinant TNFα was obtained from Knoll Pharmaceuticals (Whippany, NJ). Intelerleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) was purchased from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA). Interleukin-1β and TNFα ELISA detection polyclonal Abs were developed in our laboratory. The caspase-1 inhibitor acetyl-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-chloromethylketone (Ac-YVAD-CMK) and caspase inhibitor negative control benzyloxycarbonyl-Phe-Ala-fluoromethylketone (Z-FA-FMK) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, California).

2.2. Cell Culture

Primary monocytes were isolated from human blood by density gradient using lymphocyte separation media (Cell Grow, Media Tech, Herndon, VA) followed by CD14 positive selection (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), which yields >95% purity as determined by FACS. Isolated monocytes were cultured at 106/ml or at 12.5×106/ml in RPMI 1640 (Cambrex, East Rutherford, New Jersey), supplemented with 5% FBS (<0.0005 EU/ml) (HyClone, Logan, UT) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), in a 37°C in a humidified incubator. Monocytes were stimulated, or not, with E. coli LPS (10ng/ml) for 4 h and ATP (5mM) for the last 15 min of LPS stimulation, LPS alone, or ATP alone. The supernatants (conditioned media) from monocytes cultured at 106/ml were harvested by centrifugation (5 min; 3,600 rpm) and analyzed for cytokine release by ELISA and IFNγ inducing activity in the KG-1 biological assay. Supernatants from monocytes cultured at 12.5×106/ml were centrifuged twice (5 min at 3,600 rpm and 15 min at 13,200rpm), analyzed for cytokine release and IFNγ inducing activity and loaded on a size-exclusion column for fractionation. KG-1 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech Inc, Herndon, VA), supplemented with 20% FBS (Atlas Biologicals, Fort Collins, CO) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a 37°C in a humidified incubator.

2.3. KG-1 Biological Assay

KG-1 cells were plated at a final cell density of 106/ml in 96-well plates and incubated with test samples (100ul of monocyte conditioned media or column fractions), recombinant proteins (at the indicated concentrations), or both, in a total volume of 300μl. In selected experiments, neutralizing agents for IL-18 (IL-18 Ab – clone 125-2H, IL-18 BP, IL-18R Ab – clone 70625), IL-1β (IL-1β Ab – clone 2805, IL-1ra), TNFα (TNFα Ab – clone 2C8) or IL-12 (IL-12 Ab – clone C8.6) were used at the indicated concentrations to neutralize the activities of the respective cytokines prior to addition of ligand, or to neutralize IL-18/IL-1 receptors prior to addition of ligand to the KG-1 cells. KG-1 supernatants were harvested after 24 h and analyzed for IFNγ release by ELISA.

2.4. ELISA

Sandwich ELISAs were used to measure cytokine release in the supernatants of monocytes and KG-1 cells [56,57].

2.5. Size-exclusion chromatography

A HiPrep16/60 Sephacryl S-100 HR chromatography column (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) was equilibrated in RPMI and calibrated with known standards from a gel filtration low molecular weight calibration kit (Amersham, Pisctaway, NJ). The conditioned media (1ml) from LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes (107/ml) from two donors were separately loaded on the column. Eluting fractions (120, 1.5ml each) were collected in glass tubes containing a final concentration of 0.1% BSA. The starting material (conditioned media loaded on column) and the eluting fractions were analyzed for the presence of cytokines (IL-1β and IL-18) by ELISA, as well as IFNγ inducing activity in the KG-1 biological assay.

2.6. Immunodepletions

Anti-human TNFα (clone 2C8) and IL-18 (clone 125-2H) Abs (5 μg/ml each) were used to immunodeplete the conditioned media from LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes. Mouse IgG1 (clone 11711) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used as an isotype control for all 3 Abs. Monocyte supernatants were pre-cleared with protein A beads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min, followed by overnight incubation with the respective Ab. Supernatants were then incubated with protein A beads (50 μl/ml, 50% slurry) for 5 hours, followed by quick centrifugation to remove the Ab-bound beads. All incubations were done at 4°C, rocking. Immunodepleted supernatants were then sterilized with 0.22μm filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and assayed for TNFα and IL-18 by ELISA and for IFNγ inducing activity in the KG-1 bioassay.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data are presented mean ± S.E.M. from ≥3 independent experiments. Comparisons were done by paired t-test with p < 0.05 defined as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. KG-1 cells release IFNγ in response to rIL-18, not rIL-1β

The acute myelomonocytic KG-1 cell line has been typically used to measure the IFNγ inducing activity of IL-18, not IL-1β [28–44]. We corroborated this by stimulating KG-1 cells with several doses of rIL-18 and rIL-1β for 24 h. As expected, KG-1 cells released minimal amounts of IFNγ in response to rIL-1β, compared to rIL-18 (Fig. 1). Furthermore, combining rIL-18 with rIL-1β did not augment the levels of IFNγ released, compared to rIL-18 by itself.

3.2. Early release of IFNγ inducing activity by LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes

Interleukin-1β and IL-18 are known to be released by monocytes as a result of inflammasome and caspase-1 activation [12–14,58–61]. In an attempt to measure functional IL-18 in the supernatants of inflammasome activated monocytes, primary monocytes were stimulated, or not, with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 h and ATP (5 mM) for the last 15 min of LPS stimulation, LPS alone, or ATP alone. KG-1 cells were then incubated with the monocyte conditioned media for 24 h and IFNγ production was measured by ELISA. IFNγ inducing activity was detected in the conditioned media from monocytes that were stimulated with LPS in combination with ATP (Fig. 2A). This activity was significantly higher (p < 0.005) than that of monocytes stimulated with LPS only, suggesting it being due to the caspase-1 dependent cytokine, IL-18. Importantly, no IFNγ release was detected in the supernatants from ATP- or non-treated monocytes (Fig. 2A), or in the monocyte conditioned media prior to incubation with the KG-1 cells (data not shown), indicating that the KG-1 cells, not the monocytes, were the source of IFNγ.

Figure 2. Monocyte release of IFNγ inducing activity and proinflammatory cytokines in response to LPS/ATP stimulation.

Primary monocytes (106/ml) were stimulated, or not, with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 h and ATP (5mM) for the last 15 min of LPS stimulation, LPS alone, or ATP alone. (A) KG-1 cells (106/ml) were incubated with the monocyte conditioned media for 24 h. The KG-1 supernatants were then harvested and analyzed for IFNγ release by ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± S.E.M. **, p < 0.005 (n = 16) (B) Monocyte conditioned media was also assayed for IL-1β (B, i), IL-18 (B, ii), TNFα (B, iii) and IL-8 (B, iv) release by ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± S.E.M. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005. (A: n = 16), (B, i: n = 13; B, ii: n = 4; B, iii: n = 7; B, iv: n = 5). N.T., no treatment.

In addition, the monocyte conditioned media was assayed for IL-1β, IL-18, TNFα and IL-8 release by ELISA. As expected, LPS/ATP stimulation induced significantly more IL-1β (p < 0.005) and IL-18 (p < 0.05) release by monocytes compared to stimulation with LPS alone (Fig. 2B, i and ii). In contrast, release of the caspase-1 independent cytokines, TNFα and IL-8, was not different in response to LPS/ATP stimulation, compared to LPS alone (Fig. 2B, iii and iv). Furthermore, no significant cytokine levels were detected in the supernatants from ATP-stimulated or non-treated monocytes. Paradoxically, the amount of endogenous IL-18 in the monocyte supernatants (~1ng/ml, Fig. 2B, ii) was significantly lower than the amount of rIL-18 required to induce IFNγ production by KG-1 cells (Fig. 1).

3.3. The IFNγ inducing activity was not due to IL-18, but was decreased with a caspase-1 specific inhibitor

To determine whether or not the monocyte-derived IFNγ inducing activity was due to IL-18, we neutralized the activity of this cytokine in the monocyte conditioned media prior to incubation with the KG-1 cells, or neutralized the IL-18 receptors on the KG-1 cells prior to incubation with the monocyte conditioned media. To our surprise, the IFNγ inducing activity was not inhibited by IL-18 BP, a neutralizing IL-18 Ab, or a neutralizing IL-18R Ab (Fig. 3A). The IL-18 neutralizing agents were shown to be functional by their ability to completely inhibit rIL-18-induced IFNγ production (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. The IFNγ inducing activity released by LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes cannot be inhibited with IL-18 neutralizing agents.

(A) KG-1 cells (106/ml) were incubated with conditioned media from monocytes (106/ml) that were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml, 4 h) and ATP (5 mM, last 15 min) in the presence and absence of either IL-18 binding protein (IL-18 BP) (2 and 10 μg/ml), IL-18 Ab (IL-18 Ab) (2 and 10 μg/ml), or IL-18 receptor Ab (IL-18R Ab) (2 and 10 μg/ml). (B) KG-1 cells were stimulated with recombinant IL-18 (rIL-18) (50 ng/ml) in the prescence and absence of either IL-18 BP (2 μg/ml), IL-18 Ab (2 μg/ml), IL-18R Ab or (2 μg/ml). KG-1 supernatants were harvested after 24 h and IFNγ release was measured by ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (A: IL-18 BP: n = 5–12; IL-18 Ab: n = 4–11; IL-18R Ab: n = 4–8), (B: n = 3–13).

Since KG-1 cells did not release IFNγ in response to rIL-1β (Fig. 1), we decided to test whether the detected IFNγ inducing activity was caspase-1 dependent. Isolated monocytes were incubated with the specific caspase-1 inhibitor Ac-YVAD-CMK or the caspase inhibitor negative control Z-FA-FMK (25μM each), for 1 h prior to stimulation with LPS plus ATP. Consistent with a role for a caspase-1 dependent product, release of the monocyte-derived IFNγ inducing activity was inhibited by Ac-YVAD-CMK (~3.5-fold), not by Z-FA-FMK (Fig. 4A). Thus, the IFNγ inducing activity released by LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes was caspase-1 dependent. As expected, caspase-1 inhibition with Ac-YVAD-CMK decreased monocyte IL-1β release by ~3-fold and IL-18 release by ~10-fold (Fig. 4B and 4C). Importantly, Ac-YVAD-CMK treatment did not inhibit TNFα release (Fig. 4D), indicating that the inhibition of cytokine release was specific for caspase-1-dependent cytokines.

Figure 4. The monocyte-derived IFNγ inducing activity is caspase-1-dependent.

Monocytes were pre-treated with Ac-YVAD-CMK or Z-FA-FMK (25 μM each) for 1 h prior to LPS (10ng/ml, 4 h) plus ATP (5mM, last 15 min) stimulation. (A) KG-1 cells (106/ml) were incubated with the monocyte conditioned media for 24 h, followed by IFNγ ELISA on the KG-1 supernatants. In addition, the monocyte conditioned supernatants were assayed for IL-1β (B), IL-18 (C), and TNFα (D) release by ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (A: n = 5), (B: n = 3–7), (C: n = 3), (D: n = 4). N.T., no treatment.

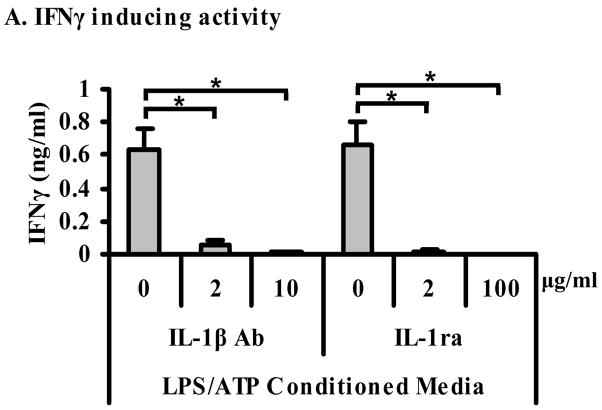

3.4. The IFNγ inducing activity can be inhibited with IL-1β neutralizing agents

KG-1 cells do not release IFNγ in response to rIL-1β (Fig. 1). However, the detected IFNγ inducing activity was caspase-1 dependent and independent of IL-18. Therefore, we decided to test the role of endogenous IL-1β as the putative IFNγ inducing factor present in the conditioned media from LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes. To our surprise the monocyte released IFNγ inducing activity was significantly (p < 0.05) and nearly completely inhibited by an IL-1β neutralizing Ab and by the IL-1 receptor antagonist protein (IL-1ra) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5). The lack of IFNγ inducing activity of rIL-1β on KG-1 cells (Fig. 1), and the presence of IL-1β-mediated IFNγ inducing activity in the monocyte conditioned media suggested the presence of a co-factor for IL-1β-mediated IFNγ production by KG-1 cells.

Figure 5. The IFNγ inducing activity released by LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes can be inhibited with IL-1β neutralizing agents.

KG-1 cells (106/ml) were incubated with conditioned media from monocytes (106/ml) that were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml, 4 h) and ATP (5 mM, last 15 min) in the presence and absence of either IL-1β Ab (IL-1β Ab) (2 and 10 μg/ml), or IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) (2 and 100 μg/ml). KG-1 supernatants were harvested after 24 h and IFNγ release was measured by ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± S.E.M. *, p < 0.05 (n = 4).

3.5. The IL-1β-dependent IFNγ inducing activity present in the monocyte supernatants is decreased upon size-exclusion fractionation

In order to test for the presence of an IL-1β cofactor for IFNγ production, we measured the IFNγ inducing activity of monocyte-released IL-1β before and after size-exclusion fractionation. The conditioned media from LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes was fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography and the starting material (conditioned media) and eluting fractions were assayed for the presence of IL-1β (Fig. 6A) and IFNγ inducing activity (Fig. 6B). As expected, IL-1β eluted at a molecular weight of ~16 kDa. Consistent with the requirement for an IL-1β cofactor, the specific activity (pg of IFNγ/pg of IL-1β) of the IL-1β positive fractions was dramatically decreased when compared to that of the starting material in two separate experiments (2 donors) (Table 1). The loss of specific activity suggested that the ability of IL-1β to induce IFNγ production requires a synergistic factor, which differs from IL-1β in molecular weight.

Figure 6. The monocyte-derived IL-1β-dependent IFNγ inducing activity decreases upon size fractionation.

Monocytes (12.5×106/ml) were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml, 4 h) and ATP (5 mM, last 15 min). Monocyte conditioned media (1 ml) was fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography (as described in the Materials and Methods section). The starting material (conditioned media loaded on column) and eluting fractions were analyzed for IL-1β by ELISA (A) and IFNγ inducing activity in the KG-1 biological assay (B). Data is representative of two separate experiments with monocytes obtained from two different donors.

Table 1.

Specific activitya of IL-1β before and after size-fractionation.

| Donor | Before | After | Fold Difference (Before/After) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 5 |

| 2 | 0.06 | 0.005 | 12 |

Specific activity = pg IFNγ/pg IL-1β

3.6. Interleukin-18 released by LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes may be partially bound to an inhibitory protein

The conditioned media from LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes and the column eluting fractions were also assayed for IL-18. It is noteworthy that the IL-18 eluted at both a high molecular weight (79 kDa) and a low molecular weight (19 kDa) peaks (data not shown). The presence of high molecular weight IL-18 suggested that IL-18 may be partially complexed to an inhibitory protein. Therefore, the low levels of IL-18 released by monocytes (Fig. 2B, ii), the high doses of rIL-18 required to induce significant IFNγ production by KG-1 cells (Fig. 1), as well as potential binding of IL-18 to an inhibitory protein may all explain the lack of IFNγ inducing activity of the monocyte-released IL-18 (Fig. 3A).

3.7. Supernatants from LPS-stimulated monocytes provide synergy to recombinant IL-1β for IFNγ induction

To search for the putative IL-1β cofactor we examined the ability of rIL-1β to induce IFNγ production when added to conditioned media from LPS-, ATP- or non-treated monocytes, which have low or non-detectable levels of endogenous IL-1β (Fig. 2B, i). Unlike the conditioned media from non- or ATP-treated monocytes, the media from LPS-stimulated monocytes provided synergy to rIL-1β for IFNγ production by the KG-1 cells (data not shown). This synergy was completely inhibited when the conditioned media from LPS-stimulated monocytes was boiled for 5 min prior to incubation with the KG-1 cells (data not shown), indicating that the potential synergistic factor(s) is most likely an LPS-induced protein.

3.8. Interleukin-1β synergizes with TNFα for IFNγ production

Tumor necrosis factor-α is a prominent pro-inflammatory cytokine released immediately following LPS stimulation that is known to synergize with IL-1β in the induction of fever, inflammation and tissue damage [9,45–49]. Moreover, it is one of the primary response cytokines induced upon LPS stimulation [1–4]. Therefore, we tested the potential role of TNFα as the IL-1β cofactor for IFNγ production by KG-1 cells. KG-1 cells were incubated with conditioned media from LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes in the presence and absence of a TNFα neutralizing Ab, IL-1β Ab, or both. Each of these conditions resulted in significant inhibition of IFNγ production (p < 0.005) (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7. Recombinant TNFα synergizes with endogenous IL-1β for IFNγ production by KG-1 cells.

(A) KG-1 cells (106/ml) were incubated with conditioned media from monocytes (106/ml) that were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml, 4 h) and ATP (5 mM, last 15 min) in the presence and absence of either TNFα Ab, IL-1β Ab, or both (10 μg/ml each) (n = 3–9). (B) Conditioned media from LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes were immunodepleted of TNFα. KG-1 cells were incubated with the non-depleted and immunodepleted conditioned media (n = 7). In addition, rTNFα (0.1, 1, 10, 100 ng/ml) (n = 3–5), or rTNFα (10, 100 ng/ml) plus IL-1ra (10 μg/ml) (n = 3) were added to the immunodepleted supernatants prior to incubation with KG-1 cells (106/ml). (C) Supernatants from LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes were immunodepleted of IL-18. Mouse IgG1 was used as an isotype control for the IL-1β, TNFα and IL-18 Abs. KG-1 cells were incubated with the immunodepleted or non-depleted supernatants (n = 3). (A – C) KG-1 supernatants were harvested after 24 h and IFNγ release was measured by ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± S.E.M. **, p < 0.005.

We then immunodepleted endogenous TNFα from the conditioned media from LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes (Fig. 7B) (immunodepletions were confirmed by ELISA - data not shown), and incubated KG-1 cells with the non-depleted and immunodepleted conditioned media. Immunodepletion of TNFα resulted in significant inhibition of IFNγ inducing activity (p < 0.005). Furthermore, rTNFα added to the TNFα-immunodepleted conditioned media restored the IFNγ inducing activity, and this effect was completely inhibited with IL-1ra. Importantly, rTNFα by itself did not induce IFNγ production at doses ranging from 0.1 to 100 ng/ml. As controls, immunodepletions done with an IL-18 Ab and IgG1 isotype control Ab (IgG1 Ab) (Fig. 7C) showed no significant inhibition of IFNγ inducing activity. All together, these results support a novel synergistic role for IL-1β and TNFα in IFNγ production by the KG-1 monocytic cell line.

3.9. Fractionated IL-1β recovers specific activity in the presence of rTNFα

To confirm that the loss of specific activity of fractionated endogenous IL-1β (Fig. 5 and Table 1) was due to its separation from TNFα, we measured the IFNγ inducing activity of fractionated IL-1β alone, plus rTNFα, or plus rTNFα and IL-1ra (Fig. 8). In agreement with our previous finding, fractionated IL-1β acquired IFNγ inducing activity when combined with rTNFα. This IFNγ inducing activity was completely inhibited by IL-1ra.

Figure 8. rTNFα synergizes with fractionated IL-1β for IFNγ production by KG-1 cells.

KG-1 cells (106/ml) were incubated with monocyte-derived fractionated IL-1β (Fig. 6) in the presence or absence of rTNFα (10 ng/ml), or rTNFα plus IL-1ra (10 μg/ml). KG-1 supernatants were harvested after 24 h and IFNγ release was measured by ELISA. Results are shown as two separate experiments with endogenous IL-1β derived from monocytes obtained from two different donors.

3.10. rTNFα synergizes with rIL-1β as well as rIL-1α and rIL-18 for IFNγ production inKG-1 cells

Finally, we incubated KG-1 cells with rIL-1β, rIL-1α, rIL-18 and rTNFα (10 ng/ml each) or with different combinations of these cytokines and measured IFNγ released by ELISA (Fig. 9). Interestingly, rTNFα synergized not only with the caspase-1rIL-1β, but also with rIL-18 and rIL-1α, indicating that TNFα may be a synergistic factor for IFNγ production in combination with members of the IL-1 family in general.

Figure 9. rTNFα synergizes with rIL-1β, rIL-1α and rIL-18 for IFNγ production by KG-1 cells.

KG-1 cells (106/ml) were incubated with either rIL-1β, rIL-1α, rIL-18, or rTNFα (10 ng/ml each) and different combinations of these cytokines. KG-1 supernatants were harvested after 24 h and IFNγ release was measured by ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3).

4. Discussion

In an effort to study the role of inflammasome-mediated events in the release of biologically active IL-18, we tested the IFNγ inducing capability of LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes on KG-1 cells. As others had previously concluded, e.g. Pirhonen et al. [44], we surmised that the presence of antigenic IL-18 in our samples in conjunction with IFNγ induction in the KG-1 cell line proved that the detected IFNγ inducing activity was due to IL-18. However, to our surprise, 3 different IL-18 neutralizing agents did not inhibit the IFNγ inducing activity present in the monocyte conditioned media. Since rIL-1β did not elicit a strong IFNγ response on KG-1 cells we decided to test whether the detected activity was due to a caspase-1 dependent or independent product of LPS/ATP stimulation. In agreement with ATP being an activator of caspase-1 in combination with LPS, the IFNγ inducing activity was proven to be caspase-1 dependent using a specific caspase-1 inhibitor.

Given the fact that IL-1β and IL-18 are the most well-known caspase-1 dependent cytokines [7–11] and despite the fact that KG-1 cells did not release IFNγ in response to rIL-1β, we decided to rule out the possibility of IL-1β being responsible for the activity. To our surprise, we were able to nearly completely inhibit the monocyte-derived IFNγ inducing activity with 2 different IL-1β neutralizing agents. Since KG-1 cells did not release IFNγ in response to rIL-1β alone, we hypothesized that IL-1β may require a synergistic factor to induce IFNγ release by KG-1 cells. Through size-fractionation, neutralization and immunodepletion experiments we uncovered for the first time that IL-1β can synergize with TNFα for IFNγ production in KG-1 cells.

IL-1β has been shown to synergize with TNFα for the induction of various early pro-inflammatory genes such as chemokines, endothelial adhesion molecules and iNOS. [9,45–49]. However, our results are unique in light of the facts that IL-1β is not generally recognized as a potent IFNγ inducing factor, and that IL-1β and TNFα have never been shown to synergize for IFNγ production. In the case of IL-1β, only a few reports have implicated this cytokine in IFNγ production in synergy with IL-2 or IL-12 in NK and T cells [18,50–55]. IL-12 is a monocyte-derived cytokine and a secondary response gene product that is not likely to be released within 4 h of LPS/ATP stimulation of monocytes. However, prior to discovering the role of TNFα as the synergistic factor for IL-1β-mediated IFNγ production, we stimulated KG-1 cells directly with rIL-1β + rIL-12 and found no synergy between these cytokines (data not shown).

In the case of TNFα, this cytokine has been previously implicated in IFNγ induction in tumor macrophages as part of the tumor angiogenic switch [62]. Moreover, TNF and IL-12 are costimulators of IFNγ in SCID mice with listeriosis; S. epidermis-induced IFNγ production in whole blood is IL-18-, IL-12- and TNFα-dependent, but IL-1 independent; and C. albicans-induced IFNγ production in whole blood is IL-18-, IL-12-and IL-1β-dependent, and to a lesser degree TNFα-dependent [63]. Therefore, the role of IL-1 cytokines and TNFα in IFNγ production had been previously suggested in neutralization experiments, however the strong synergy between these cytokines for IFNγ production has not been previously reported.

In summary, we have found a novel synergistic role for TNFα and IL-1 cytokines (IL-1β/α and IL-18) in IFNγ production by KG-1 cells. Moreover, IL-18 released from LPS/ATP-treated monocytes was non-functional (did not induce IFN-γ release by KG-1 cells), due either to sub-optimal levels, as suggested by ELISA, or to it being bound to an inhibitory protein, as suggested by size-exclusion chromatography. Importantly, KG-1 cells should be used with caution in biological assays intended to measure functional IL-18 from biological samples. This is particularly true since both, IL-1β and TNFα, are released concurrently with IL-18 upon pathogen challenge and IL-18 present in biological samples such as serum or conditioned media may be bound to an inhibitory protein(s). In the case of IL-1α, this cytokine might not have played a significant IFNγ inducing role, in synergy with TNFα, in the monocyte conditioned media since a specific IL-1β neutralizing Ab resulted in almost complete inhibition of KG-1 IFNγ production (Fig. 5).

The KG-1 cell line has been typically used to measure the IFNγ inducing activity of IL-18 [28–44]. Moreover, TNFα has been shown to upregulate the expression of the IL-18R in KG-1 cells, making these cells even more sensitive to IL-18-induced IFNγ production [64]. Hence, KG-1 cells are often pre-treated with TNFα prior to incubation with IL-18 [33–38,41]. However, when we tested the role of TNFα in IL-1R expression upregulation, we did not detect any significant changes (data not shown). Therefore, the mechanism of synergy between IL-1 cytokines and TNFα most likely involves receptor upregulation in the case of IL-18, and well as another unknown mechanism in the case of IL-1β/α and IL-18.

Importantly, our results support the conclusion that signaling events and induced genes common to the IL-1R and the IL-18R, which both belong to the IL-1R family, may be crucial in the synergy between members of the IL-1 family of cytokines (IL-1α/β and IL-18) and TNFα for IFNγ production in the KG-1 cell line. Alternatively, TNFα may upregulate cell surface expression of the IL-1R in a similar manner as it upregulates expression of the IL-18R in KG-1 cells. Studies are underway to investigate primary cell types of the monocytic lineage, which may behave in a similar manner as KG-1 cells, and the potential mechanism of synergy between IL-1 family members and TNFα in KG-1 cells at the receptor, intracellular signaling, or gene induction level.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mikhail Gavrilin and Sudarshan Seshadri for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway CA., Jr A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388(6640):394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin WJ, Yeh WC. Implication of Toll-like receptor and tumor necrosis factor alpha signaling in septic shock. Shock. 2005;24(3):206–209. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000180074.69143.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein DR. Toll-like receptors and other links between innate and acquired alloimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16(5):538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle SL, O’Neill LA. Toll-like receptors: from the discovery of NFkappaB to new insights into transcriptional regulations in innate immunity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72(9):1102–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen F, Castranova V, Shi X, Demers LM. New insights into the role of nuclear factor-kappaB, a ubiquitous transcription factor in the initiation of diseases. Clin Chem. 1999;45(1):7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmody RJ, Chen YH. Nuclear factor-kappaB: activation and regulation during toll-like receptor signaling. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4(1):31–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delaleu N, Bickel M. Interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-18: regulation and activity in local inflammation. Periodontol 2000. 2004;35:42–52. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6713.2004.003569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-18, and the interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinarello CA. The IL-1 family and inflammatory diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(5 Suppl 27):S1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gracie JA, Robertson SE, McInnes IB. Interleukin-18. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73(2):213–224. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0602313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinarello CA. Interleukin-18. Methods. 1999;19(1):121–132. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O’Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, Lee WP, Weinrauch Y, Monack DM, Dixit VM. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440(7081):228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franchi L, Kanneganti TD, Dubyak GR, Nunez G. Differential requirement of P2X7 receptor and intracellular K+ for caspase-1 activation induced by intracellular and extracellular bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(26):18810–18818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruz CM, Rinna A, Forman HJ, Ventura AL, Persechini PM, Ojcius DM. ATP activates a reactive oxygen species-dependent oxidative stress response and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(5):2871–2879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608083200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbulescu K, Becker C, Schlaak JF, Schmitt E, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Neurath MF. IL-12 and IL-18 differentially regulate the transcriptional activity of the human IFN-gamma promoter in primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1998;160(8):3642–3647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakahira M, Ahn HJ, Park WR, Gao P, Tomura M, Park CS, Hamaoka T, Ohta T, Kurimoto M, Fujiwara H. Synergy of IL-12 and IL-18 for IFN-gamma gene expression: IL-12-induced STAT4 contributes to IFN-gamma promoter activation by up-regulating the binding activity of IL-18-induced activator protein 1. J Immunol. 2002;168(3):1146–1153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson D, Shibuya K, Mui A, Zonin F, Murphy E, Sana T, Hartley SB, Menon S, Kastelein R, Bazan F, O’Garra A. IGIF does not drive Th1 development but synergizes with IL-12 for interferon-gamma production and activates IRAK and NFkappaB. Immunity. 1997;7(4):571–581. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tominaga K, Yoshimoto T, Torigoe K, Kurimoto M, Matsui K, Hada T, Okamura H, Nakanishi K. IL-12 synergizes with IL-18 or IL-1beta for IFN-gamma production from human T cells. Int Immunol. 2000;12(2):151–160. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu D, Chan WL, Leung BP, Hunter D, Schulz K, Carter RW, McInnes IB, Robinson JH, Liew FY. Selective expression and functions of interleukin 18 receptor on T helper (Th) type 1 but not Th2 cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188(8):1485–1492. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshimoto T, Takeda K, Tanaka T, Ohkusu K, Kashiwamura S, Okamura H, Akira S, Nakanishi K. IL-12 up-regulates IL-18 receptor expression on T cells, Th1 cells, and B cells: synergism with IL-18 for IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1998;161(7):3400–3407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frucht DM, Fukao T, Bogdan C, Schindler H, O’Shea JJ, Koyasu S. IFN-gamma production by antigen-presenting cells: mechanisms emerge. Trends Immunol. 2001;22(10):556–560. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukao T, Matsuda S, Koyasu S. Synergistic effects of IL-4 and IL-18 on IL-12-dependent IFN-gamma production by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;164(1):64–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gessani S, Belardelli F. IFN-gamma expression in macrophages and its possible biological significance. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1998;9(2):117–123. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(98)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golab J, Zagozdzon, Stoklosal T, Kaminski R, Kozar K, Jakobisiak M. Direct stimulation of macrophages by IL-12 and IL-18--a bridge too far? Immunol Lett. 2000;72(3):153–157. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munder M, Mallo M, Eichmann K, Modolell M. Murine macrophages secrete interferon gamma upon combined stimulation with interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-18: A novel pathway of autocrine macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 1998;187(12):2103–2108. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munder M, Mallo M, Eichmann K, Modolell M. Direct stimulation of macrophages by IL-12 and IL-18 - a bridge built on solid ground. Immunol Lett. 2001;75(2):159–160. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stober D, Schirmbeck R, Reimann J. IL-12/IL-18-dependent IFN-gamma release by murine dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;167(2):957–965. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohka H, Yoshino T, Iwagaki H, Sakuma I, Tanimoto T, Matsuo Y, Kurimoto M, Orita K, Akagi T, Tanaka N. Interleukin-18/interferon-gamma-inducing factor, a novel cytokine, up-regulates ICAM-1 (CD54) expression in KG-1 cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64(4):519–527. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konishi K, Tanabe F, Taniguchi M, Yamauchi H, Tanimoto T, Ikeda M, Orita K, Kurimoto M. A simple and sensitive bioassay for the detection of human interleukin-18/interferon-gamma-inducing factor using human myelomonocytic KG-1 cells. J Immunol Methods. 1997;209(2):187–191. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taniguchi M, Nagaoka K, Kunikata T, Kayano T, Yamauchi H, Nakamura S, Ikeda M, Orita K, Kurimoto M. Characterization of anti-human interleukin-18 (IL-18)/interferon-gamma-inducing factor (IGIF) monoclonal antibodies and their application in the measurement of human IL-18 by ELISA. J Immunol Methods. 1997;206(1–2):107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soos JM, Polsky RM, Keegan SP, Bugelski P, Herzyk DJ. Identification of natural antibodies to interleukin-18 in the sera of normal humans and three nonhuman primate species. Clin Immunol. 2003;109(2):188–196. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsukuma E, Kato Z, Omoya K, Hashimoto K, Li A, Yamamoto Y, Ohnishi H, Hiranuma H, Komine H, Kondo N. Development of fluorescence-linked immunosorbent assay for high throughput screening of interferon-gamma. Allergol Int. 2006;55(1):49–54. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.55.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiang Y, Moss B. IL-18 binding and inhibition of interferon gamma induction by human poxvirus-encoded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(20):11537–11542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novick D, Kim SH, Fantuzzi G, Reznikov LL, Dinarello CA, Rubinstein M. Interleukin-18 binding protein: a novel modulator of the Th1 cytokine response. Immunity. 1999;10(1):127–136. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SH, Azam T, Novick D, Yoon DY, Reznikov LL, Bufler P, Rubinstein M, Dinarello CA. Identification of amino acid residues critical for biological activity in human interleukin-18. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(13):10998–11003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108311200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faggioni R, Cattley RC, Guo J, Flores S, Brown H, Qi M, Yin S, Hill D, Scully S, Chen C, Brankow D, Lewis J, Baikalov C, Yamane H, Meng T, Martin F, Hu S, Boone T, Senaldi G. IL-18-binding protein protects against lipopolysaccharide- induced lethality and prevents the development of Fas/Fas ligand-mediated models of liver disease in mice. J Immunol. 2001;167(10):5913–5920. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esteban DJ, Nuara AA, Buller RM. Interleukin-18 and glycosaminoglycan binding by a protein encoded by Variola virus. J Gen Virol. 2004;85(Pt 5):1291–1299. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bufler P, Azam T, Gamboni-Robertson F, Reznikov LL, Kumar S, Dinarello CA, Kim SH. A complex of the IL-1 homologue IL-1F7b and IL-18-binding protein reduces IL-18 activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(21):13723–13728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aizawa Y, Akita K, Taniai M, Torigoe K, Mori T, Nishida Y, Ushio S, Nukada Y, Tanimoto T, Ikegami H, Ikeda M, Kurimoto M. Cloning and expression of interleukin-18 binding protein. FEBS Lett. 1999;445(2–3):338–342. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukushima K, Ikehara Y, Yamashita K. Functional role played by the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor glycan of CD48 in interleukin-18-induced interferon-gamma production. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(18):18056–18062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413297200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu C, Sakorafas P, Miller R, McCarthy D, Scesney S, Dixon R, Ghayur T. IL-18 receptor beta-induced changes in the presentation of IL-18 binding sites affect ligand binding and signal transduction. J Immunol. 2003;170(11):5571–5577. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bachmann M, Dragoi C, Poleganov MA, Pfeilschifter J, Muhl H. Interleukin-18 directly activates T-bet expression and function via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-kappaB in acute myeloid leukemia-derived predendritic KG-1 cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(2):723–731. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kojima H, Aizawa Y, Yanai Y, Nagaoka K, Takeuchi M, Ohta T, Ikegami H, Ikeda M, Kurimoto M. An essential role for NF-kappa B in IL-18-induced IFN-gamma expression in KG-1 cells. J Immunol. 1999;162(9):5063–5069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pirhonen J, Sareneva T, Kurimoto M, Julkunen I, Matikainen S. Virus infection activates IL-1 beta and IL-18 production in human macrophages by a caspase-1-dependent pathway. J Immunol. 1999;162(12):7322–7329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romero LI, Tatro JB, Field JA, Reichlin S. Roles of IL-1 and TNF-alpha in endotoxin-induced activation of nitric oxide synthase in cultured rat brain cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(2 Pt 2):R326–R332. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.2.R326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okuno T, Andoh A, Bamba S, Araki Y, Fujiyama Y, Fujiyama M, Bamba T. Interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha induce chemokine and matrix metalloproteinase gene expression in human colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(3):317–324. doi: 10.1080/003655202317284228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dinarello CA. Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;118(2):503–508. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dagia NM, Goetz DJ. A proteasome inhibitor reduces concurrent, sequential, and long-term IL-1 beta- and TNF-alpha-induced ECAM expression and adhesion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285(4):C813–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00102.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andoh A, Takaya H, Saotome T, Shimada M, Hata K, Araki Y, Nakamura F, Shintani Y, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. Cytokine regulation of chemokine (IL-8, MCP-1, and RANTES) gene expression in human pancreatic periacinar myofibroblasts. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(1):211–219. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hunter CA, Chizzonite R, Remington JS. IL-1 beta is required for IL-12 to induce production of IFN-gamma by NK cells. A role for IL-1 beta in the T cell-independent mechanism of resistance against intracellular pathogens. J Immunol. 1995;155(9):4347–4354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hunter CA, Timans J, Pisacane P, Menon S, Cai G, Walker W, Aste-Amezaga M, Chizzonite R, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA. Comparison of the effects of interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin-1 beta and interferon-gamma-inducing factor on the production of interferon-gamma by natural killer. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27(11):2787–2792. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Turner SC, Chen KS, Ghaheri BA, Ghayur T, Carson WE, Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells: a unique innate immunoregulatory role for the CD56(bright) subset. Blood. 2001;97(10):3146–3151. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Ponnappan A, Mehta V, Wewers MD, Caligiuri MA. Interleukin-1beta costimulates interferon-gamma production by human natural killer cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(3):792–801. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<792::aid-immu792>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Le J, Lin JX, Henriksen-DeStefano D, Vilcek J. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced interferon-gamma production: roles of interleukin 1 and interleukin 2. J Immunol. 1986;136(12):4525–4530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skeen MJ, Ziegler HK. Activation of gamma delta T cells for production of IFN-gamma is mediated by bacteria via macrophage-derived cytokines IL-1 and IL-12. J Immunol. 1995;154(11):5832–5841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herzyk DJ, Berger AE, Allen JN, Wewers MD. Sandwich ELISA formats designed to detect 17 kDa IL-1 beta significantly underestimate 35 kDa IL-1 beta. J Immunol Methods. 1992;148(1–2):243–254. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90178-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marsh CB, Gadek JE, Kindt GC, Moore SA, Wewers MD. Monocyte Fc gamma receptor cross-linking induces IL-8 production. J Immunol. 1995;155(6):3161–3167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tschopp J, Martinon F, Burns K. NALPs: a novel protein family involved in inflammation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(2):95–104. doi: 10.1038/nrm1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Petrilli V, Papin S, Tschopp J. The inflammasome. Curr Biol. 2005;15(15):R581. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10(2):417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Agostini L, Martinon F, Burns K, McDermott MF, Hawkins PN, Tschopp J. NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle-Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity. 2004;20(3):319–325. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee H, Baek S, Joe SJ, Pyo SN. Modulation of IFN-gamma production by TNF-alpha in macrophages from the tumor environment: significance as an angiogenic switch. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6(1):71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Netea MG, Stuyt RJ, Kim SH, van der Meer JW, Kullberg BJ, Dinarello CA. The role of endogenous interleukin (IL)-18, IL-12, IL-1beta, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the production of interferon-gamma induced by Candida albicans in human whole-blood cultures. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(7):963–970. doi: 10.1086/339410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakamura S, Otani T, Okura R, Ijiri Y, Motoda R, Kurimoto M, Orita K. Expression and responsiveness of human interleukin-18 receptor (IL-18R) on hematopoietic cell lines. Leukemia. 2000;14(6):1052–1059. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]