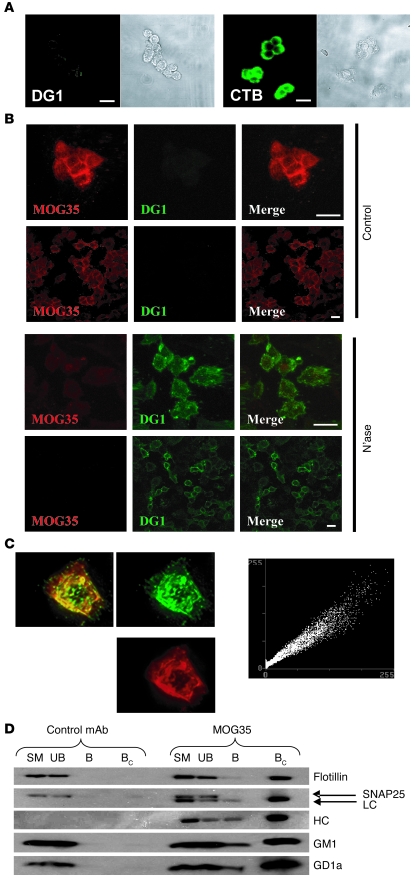

Figure 5. Localization of GM1 and GD1a to raft fractions in PC12 cells.

(A) PC12 cell immunostaining (original magnification, ×40). DG1 binding to PC12 cells (shown in phase contrast) is not detectable despite the presence of GM1, as shown by CTB staining of cells. Scale bars: 15 μm. (B) Effect of neuraminidase on DG1 and MOG35 binding to PC12 cells. Double staining reveals that control cells are positively stained with MOG35 (TRITC), with no binding of DG1 (FITC). Following neuraminidase treatment, MOG35 staining is diminished, with a concomitant increase in DG1 binding. Scale bars: 15 μm (images acquired at ×40 magnification). (C) GM1 and GD1a pixel-by-pixel colocalization. FITC and TRITC (anti-GM1 and anti-GD1a, respectively) images (×63 magnification) from double-stained PC12 cells, with colocalization appearing as yellow overlap. Plane-by-plane colocalization (linear scatter plot) shows strong colocalization. (D) Western blot of raft immunoprecipitation based on MOG35 binding, allowing isolation of GD1a-positive rafts by anti-mouse IgG–coated beads. In irrelevant antibody–incubated cells, no rafts were isolated by anti-mouse IgG–coated beads. Bound sample was concentrated (×10) to amplify any potentially weak signal. In MOG35-incubated cells, a population of rafts was isolated by the beads. Isolated fractions contained the raft-associated protein flotillin, but not SNAP25, which was taken as evidence that the raft extraction procedure did not lead to coalescence of the heterogeneous raft population. Bound fractions also contained both the light chain (LC) and heavy chain (HC) of the anti-GD1a antibody, and the isolated rafts were positive for both GM1 and GD1a. SM, starting material; UB, unbound; B, bound; BC, bound concentrated.