Abstract

Derivatives of 3β-amino-5-cholestene (3β-cholesterylamine) are of substantial interest as cellular probes and have potential medicinal applications. However, existing syntheses of 3β-amino-5-cholestene are of limited preparative utility. We report here a practical method for the stereoselective preparation of 3β-amino-5-cholestene, 3β-chloro-5-cholestene, 3β-bromo-5-cholestene, and 3β-iodo-5-cholestene from inexpensive cholesterol. A sequential i-steroid/retro-i-steroid rearrangement promoted by boron trifluoride etherate and trimethylsilyl azide converted cholest-5-en-3β-ol methanesulfonate to 3β-azido-cholest-5-ene with retention of configuration in 93% yield.

Synthetic mimics of cholesterol represent important molecular tools in the fields of bioorganic / medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. Cholesterol derivatives have been used to facilitate the delivery of siRNA,1 enhance DNA transfection,2 probe cellular membrane subdomains,3 and have been proposed for tumor targeting applications.4 The cationic cholesterol mimic 3β-amino-5-cholestene (3β-cholesterylamine) is of particular interest because of its high affinity for phospholipid membranes.5 Derivatives of 3β-amino-5-cholestene have been used to construct photoaffinity probes,6 and related aminosteroids,7 including squalamine,8,9 exhibit antimicrobial acitivity. N-Alkyl derivatives of 3β-amino-5-cholestene can insert into plasma membranes of living mammalian cells and cycle between the cell surface and early/recycling endosomes, mimicking the membrane trafficking of many cell surface receptors.10 These compounds are under investigation as tools for drug delivery,11 and when linked to endosome disruptive peptides12 can deliver molecules into the cytosol and nucleus of mammalian cells.

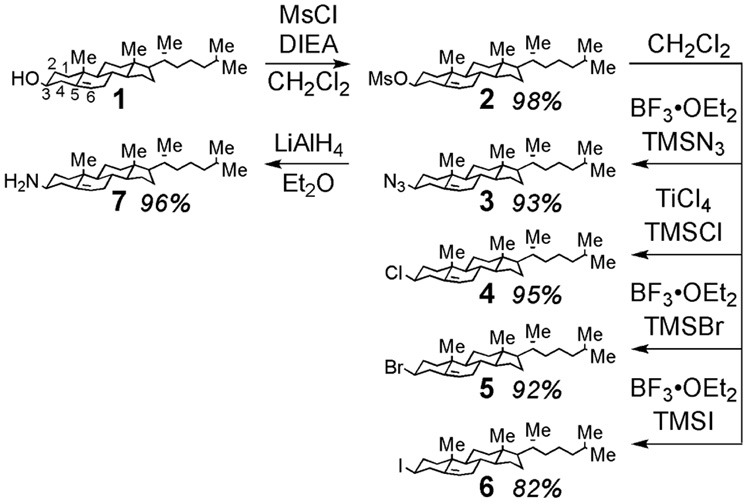

Windaus13 was the first to report that reaction of cholesteryl chloride with ammonia, or reduction of cholestenone oxime, provides 3-substituted cholesterylamines in modest yields. More recently, stereoselective syntheses of 3β-azido-5-cholestene, an important precursor to 3β-amino-5-cholestene, have involved conversion of cholesterol to epicholesterol followed by a Mitsunobu reaction with hydrazoic acid5,14 or treatment of 6β-methoxy-3α,5-cyclo-5α-cholestane and related compounds with hydrazoic acid.6,15,16 However, because of participation of the homoallylic double bond at the C5 position of the steroid, substitution reactions of cholesterol and derivatives can suffer from poor stereoselectivity, elimination, and rearrangement.17–21 These complications limit existing synthetic methods to small-scale preparation of 3β-azido-5-cholestene. To overcome this limitation, we report here a practical and efficient two step method for the synthesis of 3β-azido-5-cholestene from cholesterol. As shown in Scheme 1, this new approach, involving conversion of cholesterol (1) to the mesylate (2), followed by treatment with trimethylsilyl azide (TMSN3) and boron trifluoride etherate (BF3•OEt2) in dichloromethane, allows preparation of multi-gram quantities of pure 3β-azido-5-cholestene (3) in high yield. Subsequent reduction of 3β-azido-5-cholestene (3) with LiAlH414 provided 3β-amino-5-cholestene (7) in 96% yield (1 mmol scale). Alternatively, 7 could be obtained in 89% yield by hydrogenation of 3 in THF over 10% palladium on carbon. The high efficiency of each step of this synthesis allowed the preparation of 3 on a 100-gram scale (see the Supporting Information for details).

Scheme 1.

Optimized synthesis of 3β-amino-5-cholestene (7) and related 3β derivatives (2–6) from cholesterol (1). Yields represent reactions on a 1 mmol scale.

We additionally examined the utility of other TMS derivatives for preparation of 3β-substituted cholestenes. Correspondingly, as shown in Scheme 1, 3β-chloro-5-cholestene (4), 3β-bromo-5-cholestene (5), and 3β-iodo-5-cholestene (6) were synthesized in high yield from Lewis acids and cognate TMS compounds. This approach is particularly useful for preparation of compounds 5 and 6 due to their high susceptibility to elimination reactions.

Our rationale for investigating this approach was inspired in part by reports22,23 of the use of TMSN3 and Lewis acids in neighboring group-assisted glycosylation reactions that proceed with overall retention of configuration. Moreover, as elucidated by Shoppee21 and Winstein,24,25 cholesterol and reactive derivatives have been shown to undergo solvolysis with retention of 3β-configuration via the involvement of a non-classical carbocation that is formed by neighboring participation of the homoallylic alkene. This homoallylic carbocation reacts rapidly at the C6 position of the steroid to afford 6β-substituted-3α,5-cyclosteroids through a process termed the i-steroid rearrangement. Slower reaction of this cation at the C3 position yields cholesteryl 3β-derivatives.26,27 Based on these precedents, we hypothesized that TMSN3 and Lewis acids might efficiently convert 2 into 3 with retention of configuration.

Table 1 lists our investigation of the effects of different Lewis acids and TMSN3 on the conversion of 2 to 3. Among the Lewis acids investigated, the addition of two equivalents of BF3•OEt2 at ambient temperature (22 °C) for 2 hours proved optimal, providing 3 in 93% yield. In addition to azide 3, SnCl4, TiCl4, and AlCl3 generated 3β-chloro-cholest-5-ene (4) as a major byproduct. Reaction of fluoride derived from BF3•OEt2 with TMSN3 is presumably involved in the production of the nucleophilic azide, and the high stability of TMSF likely prevents formation of byproducts compared to the chlorinated Lewis acids. In control experiments, studies of the corresponding 3α-mesylate (8) and the dihydro analogue (9) revealed that both the 3β-configuration of 2 and the C5 alkene were required for reaction of 2 with BF3•OEt2 / TMSN3. These results are consistent with previous studies of solvolytic rate enhancements of cholesterol derivatives that compared the corresponding unsaturated and saturated substrates and that examined the stereospecificity of related reactions.21,28 These results indicate that the homoallylic double bond of 2 is a key participant in the outcome of this reaction.

Table 1.

Effects of Lewis acid and substrate structure on yield of 3β-azido-cholest-5-ene (3) from 2, 8, and 9.

| entry | substrate | Lewis acid | reaction conditions |

yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

SnCl4 (1 equiv) |

−20 °C, 1 h to 22 °C, 2 h |

54 (3); 36 (4) |

| 2 |  |

TiCl4 (1 equiv) |

−20 °C, 1 h to 22 °C, 2 h |

21 (3); 64 (4) |

| 3 |  |

AlCl3 (1 equiv) |

22 °C, 1 h | 57 (3); 34 (4) |

| 4 |  |

TMSOTf (1 equiv) |

22 °C, 12 h | complex mixture |

| 5 |  |

BF3•OEt2 (1 equiv) |

22 °C, 12 h | 68 (3); 19 (2) |

| 6 |  |

BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv) |

22 °C, 2 h | 93 (3) |

| 7 |  |

BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv) |

22 °C, 2 h | NR |

| 8 |  |

BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv) |

22 °C, 2 h | NR |

Reactions were run on a 1 mmol scale in anhydrous CH2Cl2 containing TMSN3 (1.1 equiv). For entries 1–4, reaction conditions were optimized to maximize the yield of 3, with products isolated by column chromatography (hexane eluent). For entries 1–3, the yields of the major byproduct, 3β-chloro-cholest-5-ene (4), are additionally listed. Recovery of starting material (2)is additionally shown in entry 5. NR: no reaction observed.

The effect of the leaving group on the reactivity of 3β-cholesteryl derivatives was probed as listed in Table 2. The less reactive tosylate (10) similarly furnished 3 in excellent yield but required a larger excess of BF3•OEt2 (5 equiv) and a longer reaction time than the mesylate (2). Interestingly, whereas BF3•OEt2 had little effect on conversion of 3β-chloro-5-cholestene (4), SnCl4 converted 50% of this compound to the azide (3). Substrates bearing poorer leaving groups, such as 11 and 1 were unreactive.

Table 2.

Effects of leaving group on yield of 3β-azido-cholest-5-ene (3)

| entry | substrate | Lewis acid | reaction conditions |

yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

BF3•OEt2 (5 equiv) |

22 °C, 3 h | 92 |

| 2 |  |

SnCl4 (1 equiv) |

−20 °C, 1 h to 22 °C, 2 h |

50 (3); 45 (4) |

| 3 |  |

BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv) |

22 °C, 2 h | trace |

| 4 |  |

BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv) |

22 °C, 2 h | NR |

| 5 |

|

BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv) |

22 °C, 2 h | NR |

Reactions were run on a 1 mmol scale in anhydrous CH2Cl2 containing TMSN3 (1.1 equiv). Recovery of starting material (4)is additionally shown in entry 2. NR: no reaction observed.

The nature of the solvent was also found to play a critical role in this reaction. Benzene could be substituted for dichloromethane (or chloroform) without appreciably diminishing the yield of 3 from 2 (92%), but required additional eqivalents of BF3•OEt2 (5 equiv) and a longer reaction time (12 h) for completion of reaction. No reaction was observed in solvents bearing heteroatoms that function as Lewis bases, including tetrahydrofuran, acetone, diethyl ether, or DMF, further emphasizing the role of the Lewis acid in activating the leaving group. Poor solubility of 2 precluded evaluation of reactivity in hexane, acetonitrile, or DMSO.

Because the conversion of 2 to 3 proceeded rapidly at ambient temperature in the presence of BF3•OEt2 and TMSN3, the course of the reaction could be readily followed by 1HNMR. As shown in Figure 1 (panel A), the acquisition of 1HNMR spectra at different time points allowed clear observation of the disappearance of signals of starting material and the emergence of product. Importantly, these experiments detected the transient appearance of a signal at 3.27 ppm (observed at 2 and 4 minutes) that did not correspond to the starting material (2) or product (3), but rather could be assigned as the C6 proton of 6β-azido-3α,5-cyclo-5α-cholestane (12), a structure that was further supported by distinctive cyclopropyl signals observed at 0.53 ppm (shown in the Supporting Information).19 This data is consistent with generation of the i-sterioid intermediate 12 derived from attack of azide on C6 of the homoallylic cation as shown in Figure 1, panel B.

Figure 1.

Examination of the conversion of 2 to 3 by 1H NMR (400 MHz). Panel A: 1H NMR spectra of 2 before (bottom spectrum) and at selected time points after the addition of TMSN3 (1 equiv) and BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv) to 2 (0.5 mmol) in CDCl3 (0.5 mL). The arrows point to signals identified as the C6 proton of 6β-azido-3α,5-cyclo-5α-cholestane (12). Panel B: Observed chemical shifts of 2, 12, and 3 and the proposed mechanism of reaction.

The NMR data shown in Figure 1, panel A, in conjunction with the necessity of both 3β-stereochemistry of the mesylate (2) and the the presence of the homoallylic double bond (Table 1) suggests that 2 is initially converted by the Lewis acid to a homoallylic carbocation that rapidly undergoes the i-steroid rearrangement and retro-i-steroid rearrangement shown in Figure 1, panel B. This mechanism is consistent with pioneering studies of related solvolysis reactions by Winstein.24,25 Winstein demonstrated25 that attack at the C6 carbon of cholesterol-derived homoallylic carbocations is kinetically favored, and the structure of the homoallylic cation engenders formation of the 6β-product over the 6α-product. Although the attack of nucleophiles at C3 of the homoallylic carbocation is slower than C6, this addition occurs to form the thermodyamic product with exclusively β-stereochemistry. This stereochemical outcome is a result of the non-classical carbocation forming a partial bond between C5 and C3 only on the alpha face of the steroid.

To further support the idea that the i-steroid rearrangement product can lead to 3, we prepared 6β-azido-3α,5-cyclo-5α-cholestane (12) by treatment of 2 with NaN3 in refluxing methanol, a modification of the method of Freiberg.19 Importantly, treatment of 12 with BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv) and TMSN3 (1 equiv) resulted in clean conversion to 3 within 2 hours at ambient temperature (data shown in the Supporting Information). In contrast, treatment of 12 with TMSN3 alone or TMSN3 and TBAF to generate the azide ion did not result in conversion to 3, indicating that the Lewis acid is required to promote the retro-i-steriod rearrangment. Treatment of 12 with excess BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv) resulted in formation of 3 within 10 minutes. However, byproducts were associated with treatment of 12 with BF3•OEt2 in the absence of TMSN3. Correspondingly, the addition of two equivalents of BF3•OEt2 and 1.1 equiv of TMSN3 to 2 proved to be optimal to both generate the homoallylic cation and convert 12 to 3 in high yield.

In summary, we developed a novel and highly efficient method for the synthesis of 3β-amino-5-cholestene and related halides. This method, which involves regiospecific and sterospecific i-steroid and retro-i-steroid rearrangements, is amenable to large-scale preparation of these compounds from inexpensive cholesterol. This approach may also be useful for the synthesis of other steroid derivatives bearing similar π-systems.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures and compound characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (CA83831) and the University of Kansas Cancer Center for financial support. This manuscript is dedicated to Professor David A. Lightner on the occasion of his retirement from the University of Nevada, Reno.

References

- 1.Wolfrum C, Shi S, Jayaprakash KN, Jayaraman M, Wang G, Pandey RK, Rajeev KG, Nakayama T, Charrise K, Ndungo EM, Zimmermann T, Koteliansky V, Manoharan M, Stoffel M. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1149–1157. doi: 10.1038/nbt1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitard B, Oudrhiri N, Vigneron JP, Hauchecorne M, Aguerre O, Toury R, Airiau M, Ramasawmy R, Scherman D, Crouzet J, Lehn JM, Lehn P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:2621–2626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato SB, Ishii K, Makino A, Iwabuchi K, Yamaji-Hasegawa A, Senoh Y, Nagaoka I, Sakuraba H, Kobayashi T. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:23790–23796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Firestone RA. Bioconjug. Chem. 1994;5:105–113. doi: 10.1021/bc00026a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kan CC, Yan J, Bittman R. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1866–1874. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spencer TA, Wang P, Li D, Russel JS, Blank DH, Huuskonen J, Fielding PE, Fielding CJ. J. Lipid Res. 2004;45:1510–1518. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400081-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salmi C, Loncle C, Vidal N, Laget M, Letourneux Y, Brunel JM. Lett. Drug Design Discov. 2008;5:169–172. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore KS, Wehrli S, Roder H, Rogers M, Forrest JN, Jr, McCrimmon D, Zasloff M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:1354–1358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salmi C, Loncle C, Vidal N, Letourneux Y, Fantini J, Maresca M, Taieb N, Pages JM, Brunel JM. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson BR. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:3607–3612. doi: 10.1039/b509866a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boonyarattanakalin S, Hu J, Dykstra-Rummel SA, August A, Peterson BR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:268–269. doi: 10.1021/ja067674f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun Q, Cai S, Peterson BR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10064–10065. doi: 10.1021/ja803380a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Windaus A, Adamla J. Berichte Der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 1911;44:3051–3058. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boonyarattanakalin S, Martin SE, Dykstra SA, Peterson BR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:16379–16386. doi: 10.1021/ja046663o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel MS, Peal WJ. J. Chem. Soc. 1963:1544–1546. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarreau FX, Khuonghuu Q, Goutarel R. Bull. Soc. Chim. France. 1963;8–9:1861–1865. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corey EJ, Nicolaou KC, Shibasaki M, Machida Y, Shiner CS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;16:3183–3186. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aneja R, Davies AP, Knaggs JA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;16:1033–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freiberg LA. J. Org. Chem. 1965;30:2476–2479. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haworth RD, Lunts LHC, Mckenna J. J. Chem. Soc. 1955:986–991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoppee CW, Summers GHR. J. Chem. Soc. 1952:3361–3374. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stimac A, Kobe J. Carbohydr. Res. 2000;324:149–160. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(99)00293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Akri K, Bougrin K, Balzarini J, Faraj A, Benhida R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:6656–6659. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosower EM, Winstein S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956;48:4347–4354. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winstein S, Kosower EM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959;81:4399–4408. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galynker I, Still WC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:4461–4464. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koen MJ, Leguyader F, Motherwell WB. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm. 1995:1241–1242. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Story PR, Clark BC. In: Carbonium Ions. Olah GA, Schleyer PvR, editors. Volume III. Wiley and Sons; 1972. pp. 1007–1016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures and compound characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.