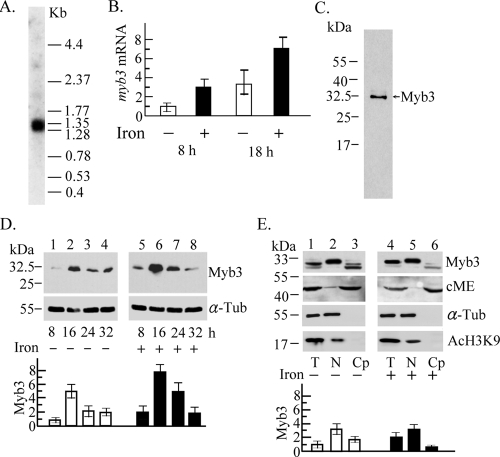

FIG. 2.

Expression of the myb3 gene in T. vaginalis. (A) Ten micrograms of mRNA purified from T. vaginalis was examined by Northern hybridization using an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled DNA probe derived from pTAha-myb3. A low-molecular-weight RNA ladder was used as the size marker (Invitrogen). (B) Relative levels of myb3 versus β-tubulin mRNA in 10 μg of cellular RNA from T. vaginalis with iron depletion (open bars) and iron repletion (closed bars) for 8 and 18 h were assayed by RT-qPCR. (C to E) Lysate from T. vaginalis in normal growth medium (C) or medium with iron depletion (−) or repletion (+) (D and E) was examined by Western blotting. Myb3 (C) or relative levels of Myb3 versus α-tubulin (α-Tub) (D and E) in samples from total lysates (T), nuclear fractions (N), or cytoplasmic fractions (Cp) of T. vaginalis exposed to iron depletion (D, lanes 1 to 4, and E, lanes 1 to 3) and iron repletion (D, lanes 5 to 8, and E, lanes 4 to 6) for different time periods (D) and for 16 h (E) were examined by Western blotting (top) using the antibodies against Myb3, cytosolic malic enzyme (cME), acetyl-histone H3 (AcH3K9), and α-Tub. The levels of Myb3 in the cytoplasmic fractions were relative to the levels of cME. The results depicted in bar graphs are the averages ± the standard error from three separate experiments.