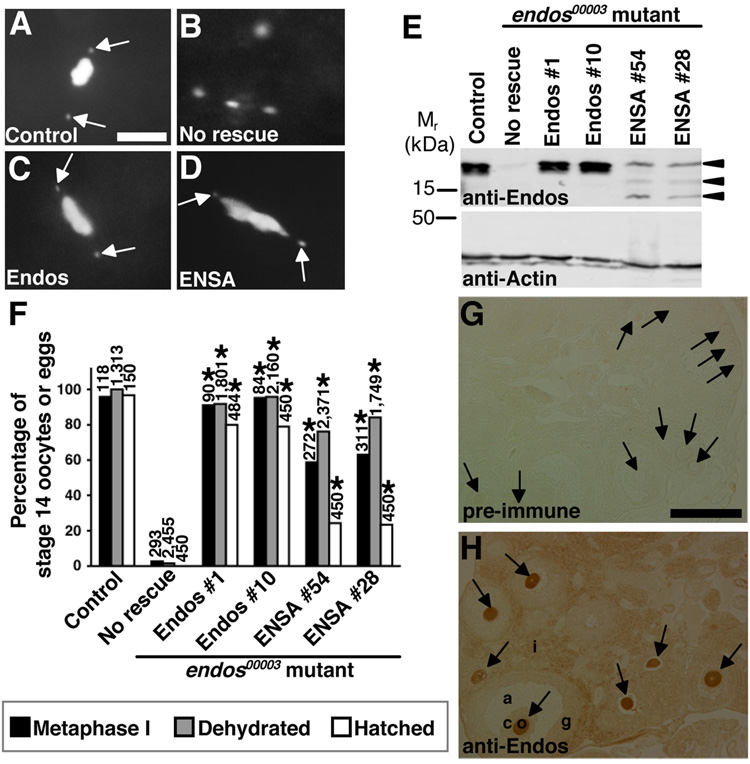

Figure 5. The function of α-endosulfine may be evolutionarily conserved.

(A–D) DAPI-stained stage 14 oocytes from control and endos00003 females expressing Endos or human α-endosulfine (ENSA). Control oocytes (A) arrested in metaphase I and endos mutant oocytes (B) with dispersed DNA. nanos-Gal4::VP16-driven germline expression of UAS-endos (C) or UAS-ENSA (D) transgenes showing endos rescue. Arrows indicate fourth chromosomes. Scale bar, 5 µm. (E) Western analysis showing ovarian expression of Endos and ENSA in rescued females. Actin used as loading control. Arrowheads indicate ENSA-specific bands (lower bands are likely degradation products), absent in “No rescue” control. (F) Quantification of endos00003 rescue. Number of stage 14 oocytes (metaphase I arrest and dehydration) or eggs (hatch rate) analyzed shown above bars. Asterisks, P<0.001. (G,H) Mouse ovary immunohistochemistry showing that anti-Endos antibodies strongly label the cytoplasm of oocytes (H), while no signal is detected by pre-immune serum (G). o, oocyte (arrows); c, cumulus cells; g, granulosa cells; a, antrum; i, interstitial cells. Scale bar, 200 µm.