Abstract

We describe two patients with fungal keratitis refractory to standard antifungal therapy whose conditions were managed with voriconazole.

The first case is a patient with endophthalmitis and corneal ulcer due to Candida parapsilosis after receiving a corneal transplant. The patient was treated with amphotericin but showed no signs of improvement. Topical voriconazole, oral voriconazole, and intravitreal voriconazole yielded signs of improvement. The second case is a 63-year-old male who underwent a month of empiric treatment with 0.2% topical amphotericin for fungal keratitis but showed no signs of improvement. Treatment was then provided with 1% voriconazole. Both cases showed effective treatment with voriconazole.

Voriconazole may be considered as a new method to treat fungal keratitis refractory to standard antifungal therapy.

Keywords: Fungus, Keratitis, Voriconazole

Voriconazole has been reported to be effective in the treatment of fungal keratitis.1-4 Jang et al.5 reported effective treatment of candida chorioretinitis with voriconazole. Sponsel et al.6 reported topical voriconazole as a novel treatment for fungal keratitis. Voriconazole has the broad spectrum coverage of the azole antifungals and has good intraocular penetration following oral administration. We report the use of topical, oral, and intravitreal voriconazole in two patients with fungal keratitis and fungal endophthalmitis.

Case 1

A 60-year-old man was admitted because of visual disturbances and ocular pain following penetrating keratoplasty in the right eye for a corneal chemical burn.

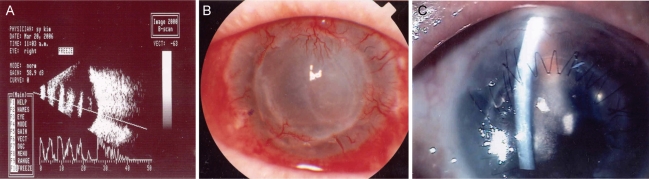

On slit lamp examination, we observed a feather-like corneal opacity, corneal infiltrations, and epithelial defects. Fungal keratitis was suspected and corneal scrapings were taken that grew C. parapsiolosis. Subconjuctival amphotericin B (1 mg), topical amphotericin B 0.125%, and levofloxaxin 0.5% were subsequently administered every hour for 16 weeks. We discontinued use of the eye solutions upon observing signs of clinical improvement and stabilization. However, 5 days later the lesion recurred. The patient was restarted on and maintained on a topical amphotericin B treatment (0.125% twice daily) for 1 year. In addition, levofloxaxin 0.5% (three times daily) and fluorometholone 0.1% (twice daily) were administered for 1 year. The lesion did not progress, but there was no change in corneal infiltration. On examination one year later, an elevated corneal lesion and increased corneal infiltration with a yellow color were observed despite the topical amphotericin B treatment. Seven days later anterior chamber hypopyon and vitreous opacity on a B-scan were observed (Fig. 1A). We immediately performed an intravitreal injection of amphotericin B 5 µg/0.1mL and vancomycin 1 mg/0.1mL. The next day there were still no signs of clinical improvement. Intravitreal voriconazole 80 µg/0.1mL and ceftazidime 2 mg/0.1mL were injected and topical voriconazole 1% was administered every 2 hours. Oral voriconazole 200 mg (twice daily) was also administered for 7 days. The patient discontinued the oral voriconazole because of abdominal pain, dry mouth, and scaling of the oral mucosa. The topical voriconazole was tolerated despite complaints of ocular burning. The patient was treated topically for 6 weeks, after which the corneal lesion and endophthalmitis had improved. The corneal opacity and endophthalmitis remained as complications of the lesion (Fig. 1B). The patient subsequently underwent another penetrating keratoplasty and demonstrated a visual acuity of 0.1 at 10 months follow-up with no signs of recurrence.

Fig. 1.

(A) Approximately 1 year later, anterior chamber hypopyon and vitreous opacity on B-scan were observed. (B) After the patient was treated with 1% topical voriconazole for 6 weeks the corneal lesion and endophthalmitis improved. The corneal opacity persisted as a complication of the lesion and endophthalmitis. (C) The patient underwent another penetrating keratoplasty and showed a visual acuity of 0.1 at follow-up. There was no sign of recurrence.

Case 2

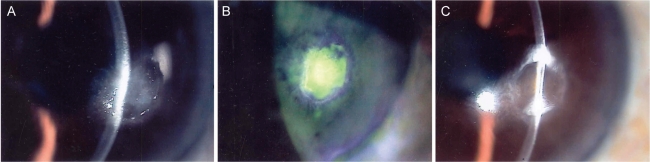

A 60-year-old man was referred to us because of a lack of improvement after a month of empiric treatment with topical amphotericin B for fungal keratitis. On our initial examination we observed a feathered corneal infiltration and a corneal ulcer (Fig. 2A). Corneal scrapings were taken. We started treatment with topical amphotericin B 0.125% and moxifloxacin 0.5%. After 10 days the culture revealed no growth and the corneal epithelium appeared healed; however, there was no change in corneal infiltration (Fig. 2B). Because of a lack of improvement in the corneal lesion a month later, a new treatment regimen was initiated with topical voriconazole 1% administered every hour. The patient complained of ocular burning but tolerated the treatment. Clinical improvement was observed two weeks later with healing of the corneal epithelium. Six weeks later we observed a decreasing density of the infiltrate and healing of the corneal epithelium; the topical voriconazole was decreased to twice daily. The patient was treated topically for 13 weeks. Following completion of the therapy, complete healing of the corneal epithelium and resolution of the corneal infiltrate were observed; however, the corneal opacity persisted (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

(A) On initial examination, a feathered corneal infiltration and a corneal ulcer were observed. (B) After 10 days the corneal epithelial appeared healed; however, there was no change in the corneal infiltration. (C) After 13 weeks we observed complete healing of the corneal epithelium and resolution of the corneal infiltrate; however, the corneal opacity persisted.

Discussion

Voriconazole, a derivative of fluconazole, is a new triazole antifungal agent.4 Like other triazoles, this voriconazole inhibits cytochrome P450 demethylase, which is essential for the synthesis of ergosterol. It is hypothesized that this adversely affects the permeability of the fungal cell membrane.7 Voriconazole has excellent oral bioavailability and a broad spectrum of activity. Therapeutic aqueous and vitreous levels are achieved after oral administration of voriconazole.8 Voriconazole showed lower MICs compared to other antifungal agents when tested against five corneal isolates of Scedosporium apiospermum,2 and it had the best in vitro susceptibility profile for 34 common fungal pathogens compared to other antifungal agents.9 Gao et al.10 reported that direct intravitreal voriconazole injections of 25 µg/mL (equivalent to 100 mg per injection in a human eye) caused no electroretinographic or histopathologic abnormalities in rodent retinas. Kramer et al.11 reported that intravitreal injection of voriconazole (100 µg/0.1mL) with pars plana vitrectomy was an effective therapy for aspergillus endophthalmitis. Lee et al.7 reported a case of drug-resistant penicillium endophthalmitis that was treated with intravitreal voriconazole injection (50 µg/ 0.1mL). In these cases, intravitreal voriconazole (80 µg/0.1mL) achieved effective concentrations. Voriconazole has been shown to be highly effective against filamentous organisms and is more potent in invasive aspergillosis than amphotericin B.12,13 According to a report by Jang et al.,5 voriconazole is also effective against candida chorioretinitis. Ozbek et al.14 reported one case of Alternaria keratitis that showed improvement with 1% topical voriconazole. In contrast, Giaconi et al.15 reported two cases of fungal keratitis caused by Fusarium oxysporum and Colletotrichum dematium that did not respond to treatment with 1% topical voriconazole. Our report indicates that 1% voriconazole is an effective treatment for candida spp. and unknown fungal keratitis. In conclusion, voriconazole is a new, promising therapy for fungal keratitis refractory to standard antifungal agents. Nevertheless, more clinical trials will be necessary to investigate the effectiveness of systemic voriconazole and corneal transplantation.

Footnotes

This case was presented in part at the Korean Ophthalmological Society's Spring Meeting in Busan, Korea in April 2007.

References

- 1.Anderson KL, Mitra S, Salouti R, et al. Fungal keratitis caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus associated with a retained intracorneal hair. Cornea. 2004;23:516–521. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000114126.63670.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah KB, Wu TG, Wilhelmus KR, Jones DB. Activity of voriconazole against corneal isolates of Scedosporium apiospermum. Cornea. 2003;22:33–36. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozbek Z, Kang S, Sivalingam J, et al. Voriconazole in the management of Alternaria keratitis. Cornea. 2006;25:242–244. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000170692.05703.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim KH, Kim MJ, Tehah HW. Management of fungal infection with topical and intracameral voriconazole. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2008;49:1054–1060. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jang GJ, Kim KS, Shin WS, Lee WK. Treatment of Candida Chorioretinitis with Voriconazole. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2005;19:73–76. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2005.19.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sponsel W, Chen N, Dang D, et al. Topical voriconazole as a novel treatment for fungal keratitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:262–268. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.262-268.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SB, Park CJ, Kim JY. A Case of Intravitreal Voriconazole for the Treatment of Drug-resistant Penicillium Endophthalmitis. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2007;48:1583–1587. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haripasad SM, Mieler WF, Holz ER, et al. Determination of vitreous, aqueous, and plasma concentration of orally administered voriconazole in humans. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:42–47. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marangon FB, Miller D, Giaconi JA, Alfonso EC. In vitro investigation of voriconazole susceptibility for keratitis and endophthalmitis fungal pathogens. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:820–825. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao H, Pennesi M, Shah K, et al. Safety of intravitreal voriconazole: electroretinographic and histopathologic studies. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2003;101:183–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer M, Kramer MR, Blau H, et al. Intravitreal voriconazole for the treatment of endogenous Aspergillus endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1184–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:408–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller GR, Rebell G, Magoon RC, et al. Intravitreal antimycotic therapy and cure of mycotic endophthalmitis caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus contaminated pseudophakos. Ophthalmic Surg. 1978;9:54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozbek Z, Kang S, Sivalingam J, et al. Voriconazole in the management of Alternaria keratitis. Cornea. 2006;25:242–244. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000170692.05703.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giaconi JA, Marangon FB, Miller D, Alfonso EC. Voriconazole and fungal keratitis: a report of two treatment failures. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2006;22:437–439. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.22.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]