Abstract

Background: The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial showed an overall advantage for operative compared with nonoperative treatment of lumbar disc herniations. Because a recent randomized trial showed no benefit for operative treatment of a disc at the lumbosacral junction (L5-S1), we reviewed subgroups within the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial to assess the effect of herniation level on outcomes of operative and nonoperative care.

Methods: The combined randomized and observation cohorts of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial were analyzed by actual treatment received stratified by level of disc herniation. Overall, 646 L5-S1 herniations, 456 L4-L5 herniations, and eighty-eight upper lumbar (L2-L3 or L3-L4) herniations were evaluated. Primary outcome measures were the Short Form-36 bodily pain and physical functioning scales and the modified Oswestry Disability Index assessed at six weeks, three months, six months, one year, and two years. Treatment effects (the improvement in the operative group minus the improvement in the nonoperative group) were estimated with use of longitudinal regression models, adjusting for important covariates.

Results: At two years, patients with upper lumbar herniations (L2-L3 or L3-L4) showed a significantly greater treatment effect from surgery than did patients with L5-S1 herniations for all outcome measures: 24.6 and 7.1, respectively, for bodily pain (p = 0.002); 23.4 and 9.9 for Short Form-36 physical functioning (p = 0.014); and −19 and −10.3 for Oswestry Disability Index (p = 0.033). There was a trend toward greater treatment effect for surgery at L4-L5 compared with L5-S1, but this was significant only for the Short Form-36 physical functioning subscale (p = 0.006). Differences in treatment effects between the upper lumbar levels and L4-L5 were significant for Short Form-36 bodily pain only (p = 0.018).

Conclusions: The advantage of operative compared with nonoperative treatment varied by herniation level, with the smallest treatment effects at L5-S1, intermediate effects at L4-L5, and the largest effects at L2-L3 and L3-L4. This difference in effect was mainly a result of less improvement in patients with upper lumbar herniations after nonoperative treatment.

Level of Evidence: Prognostic Level I. See Instructions to Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Lumbar disc herniations are the most common cause of lumbar radiculopathy, and elective discectomy provides the most immediate relief of the symptoms1-5. The majority of lumbar herniations occur at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 intervertebral disc levels, affect the L5 and S1 roots, and result in sciatica6-9. Upper level herniations (levels L2-L3 or L3-L4) are less common, may affect the L2, L3, and L4 nerve roots, and may cause a femoral radiculopathy. Patients with upper lumbar disc herniations classically present with back and thigh pain, a negative straight leg-raising test, a positive femoral stretch test, a unilaterally depressed or absent patellar reflex, sensory changes in the thigh, and often quadriceps weakness7,8,10,11.

Few clinical studies have detailed the characteristics or outcomes of patients with upper level lumbar herniations7,8,10,11. The largest prior study of which we are aware was a review by Spangfort of 2504 lumbar disc herniations that included forty-five patients with upper level herniations9. He found a greater improvement following surgery for L1-L2 and L2-L3 herniations than for L3-L4, L4-L5, and L5-S1 herniations. In a randomized trial by Osterman et al., operative outcomes were better than nonoperative treatment for patients with L4-L5 herniations but not for those with L5-S1 herniations2. Other, older retrospective studies found that the level of herniation had no significant effect on the outcomes of discectomy12-14.

The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) provides a unique opportunity to analyze the effect of lumbar disc herniation level on clinical outcomes. The purposes of this study were to describe the characteristics of patients with lumbar disc herniations at different levels and to evaluate the association between disc herniation level and treatment outcomes.

Materials and Methods

SPORT was conducted at thirteen multidisciplinary spine practices in eleven states across the United States. The human subject committees at each center approved the standardized protocol. Patients considered for inclusion in the study were over eighteen years old, had radicular pain for at least six weeks with a positive nerve root tension sign and/or neurological deficit, and had a confirmatory cross-sectional imaging study demonstrating intervertebral disc herniation at a level and side corresponding to their symptoms. Exclusion criteria included cauda equina syndrome, a progressive neurological deficit, malignancy, scoliosis of >15°, herniation cephalad to L2, prior back surgery, and other established contraindications to elective surgery.

Patients were offered participation in either a randomized or a concurrent observational cohort. Participants in the randomized cohort received computer-generated random treatment assignments blocked by center; those in the observational cohort chose their treatment with their physician. Additional details regarding the methods of randomization are available in the original articles4,5. Because of extensive crossover in the randomized cohort (that is, some patients randomized to nonoperative care received operative care and vice versa) and similar baseline characteristics and outcomes between randomized and observational patients when analyzed by treatment, the two groups were combined in this “as-treated” analysis.

The treating physician at each participating institution reviewed the imaging studies and classified the herniation by level, morphology, and location. The herniation location was classified as central, posterolateral, foraminal, or far lateral as defined by Fardon and Milette15. The herniation morphology was classified as protrusion, extrusion, or sequestered fragment15.

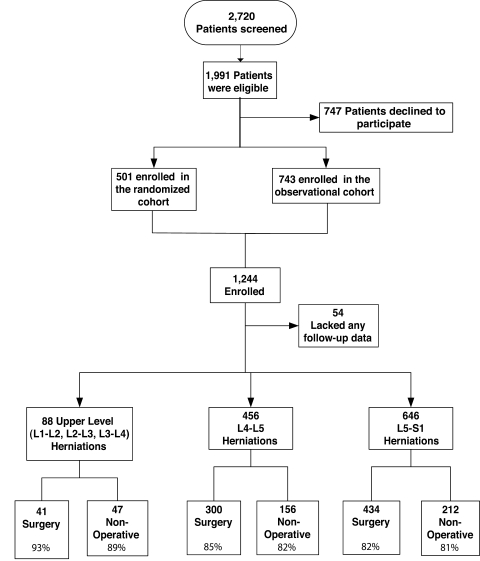

To maintain adequately sized groups for analysis, level L2-L3 and L3-L4 herniations were grouped as upper disc levels and level L4-L5 and L5-S1 herniations were each analyzed individually. After stratification by herniation level, patients were analyzed by the actual treatment received, either nonoperative therapy or operative discectomy. In these as-treated analyses, the treatment indicator was a time-varying covariate, allowing for variable times of surgery. Prior to the time of surgery, all changes from baseline were included in the estimates of the nonoperative treatment effect. Following surgery, subsequent changes in outcomes were assigned to the operative group with follow-up measured from the date of surgery. Treatment effects (defined as the change in the operative group minus the change in the nonoperative group) were evaluated by level, adjusting for important covariates (age, sex, race, marital status, work status, disability compensation status, body mass index, smoking status, joint problems, migraine headaches, any neurological deficit, baseline scores, baseline leg-symptom severity, baseline satisfaction with symptoms, self-rated health trend, study center, insurance status, herniation type, and herniation location) with use of longitudinal regression models. The longitudinal regression model used was a mixed effects model with a random effect for individual intercepts. This type of regression model accounts for the fact that measurements are made within a given individual over time and therefore these measurements may contain some internal correlation with each other. Missing data due to item nonresponse were rare because of the methods used for electronic data entry. Missed visits occurred, as seen in Figure 1, and resulted in the omission of the associated data from the analysis. This method appears to be optimal if the missing data depend only on parameters included in the longitudinal regression model16.

Fig. 1.

Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) intervertebral disc herniation enrollment and randomization. This flow diagram describes the group enrollment. The percentages in the final row of boxes are the percentage of patients seen at the time of the two-year follow-up by the treatment received within two years of enrollment.

The main outcome measures were the Short Form-36 (SF-36)17 bodily pain and physical functioning scales and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons MODEMS (Musculoskeletal Outcomes Data Evaluation and Management System) version of the Oswestry Disability Index18. The patients were evaluated at six weeks, three months, six months, one year, and two years. To determine whether the treatment effect of surgery varied with herniation level at the two-year time point, pairwise z-tests were performed to compare the estimated treatment effects between each level group.

Statistical modeling was performed with use of SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), with the procedures PROC MIXED, and S-PLUS software (version 6.2; Insightful, Seattle, Washington) was used for all other calculations. Significance was defined as a p value of 0.05 on the basis of a two-sided hypothesis test.

Results

There were 646 L5-S1 herniations, 456 L4-L5 herniations, sixty-eight L3-L4 herniations, and twenty L2-L3 herniations evaluated (Fig. 1). Fifty-four patients were excluded because no follow-up data were available. From 81% to 93% of the subjects in each subgroup provided data at the two-year visit.

Patient Characteristics

The baseline characteristics of all of the participants are displayed in Table I, according to the level of herniation. The majority of the study population (57%) was male and had a similar baseline health status (according to the bodily pain and physical functioning scales of the SF-36 and the Oswestry Disability Index) for each group. The level of herniation varied directly with age, as patients with upper level herniations were significantly older (p < 0.001), the L4-L5 group was of an intermediate age, and the L5-S1 group was the youngest. Consistent with the inclusion criterion, virtually all patients had radiating leg pain consistent with a radiculopathy. The mean leg-symptom severity score was lower at baseline for the patients with upper level herniations (13.9) than for those with L4-L5 herniations (15.4) and L5-S1 herniations (15.9). Smoking status, the duration of symptoms prior to enrollment, the time from enrollment to surgery, and participation in the randomized cohort were similar across the subgroups.

TABLE I.

Baseline Characteristics by Herniation Level in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Intervertebral Disc Herniation Randomized Cohort and Observation Cohort Combined*

| L2-L3 and L3-L4 (N = 88) | L4-L5 (N= 456) | L5-S1 (N = 646) | Overall P Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and health status | ||||

| Male patients | 54 (61%) | 275 (60%) | 354 (55%) | 0.14 |

| Age‡(yr) | 50.9 ± 10.9 | 41.8 ± 12.1 | 40.4 ± 10.3 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index‡ | 28.4 ± 6.2 | 28.2 ± 5.3 | 27.8 ± 5.6 | 0.35 |

| Height‡(ft [m]) | 5.7 ± 0.3 (1.7 ± 0.09) | 5.7 ± 0.3 (1.7 ± 0.09) | 5.7 ± 0.3 (1.7 ± 0.09) | 0.56 |

| Patients who were smokers | 20 (23%) | 112 (25%) | 149 (23%) | 0.85 |

| Patients who worked | 40 (45%) | 288 (63%) | 417 (65%) | 0.002 |

| Workers' Compensation status | 0.66 | |||

| None | 75 (85%) | 371 (81%) | 534 (83%) | |

| Receiving or pending | 13 (15%) | 84 (18%) | 110 (17%) | |

| Cohort | 0.093 | |||

| Randomized | 32 (36%) | 165 (36%) | 274 (42%) | |

| Observation | 56 (64%) | 291 (64%) | 372 (58%) | |

| Duration of symptoms | 0.20 | |||

| ≤6 wk | 14 (16%) | 68 (15%) | 83 (13%) | |

| 1.5 to 6 mo | 55 (63%) | 275 (60%) | 434 (67%) | |

| >6 mo | 19 (22%) | 113 (25%) | 129 (20%) | |

| Days to surgery‡ | 50.4 ± 194 | 84 ± 260.2 | 62.5 ± 161.9 | 0.31 |

| SF-36 bodily pain score‡ | 29.3 ± 18.5 | 25.6 ± 19.4 | 25.6 ± 17.2 | 0.20 |

| SF-36 physical functioning score‡ | 35.1 ± 22.8 | 38 ± 26.4 | 37.9 ± 25.3 | 0.59 |

| Oswestry Disability Index score‡ | 46.8 ± 20.1 | 50 ± 21.8 | 49.5 ± 21.1 | 0.42 |

| Leg symptom severity score‡ | 13.9 ± 5.3 | 15.4 ± 5.3 | 15.9 ± 5.2 | 0.003 |

| Clinical findings (no. of patients) | ||||

| Pain radiation | 87 (99%) | 444 (97%) | 629 (97%) | 0.69 |

| Straight leg-raising test—ipsilateral | 22 (25%) | 262 (57%) | 465 (72%) | <0.001 |

| Straight leg-raising test—contralateral or both | 2 (2%) | 92 (20%) | 94 (15%) | <0.001 |

| Any femoral tension sign | 38 (43%) | 34 (7%) | 17 (3%) | <0.001 |

| Any neurological deficit | 67 (76%) | 338 (74%) | 496 (77%) | 0.58 |

| Asymmetric depressed reflexes | 34 (39%) | 95 (21%) | 351 (54%) | <0.001 |

| Asymmetric decreased sensory changes | 42 (48%) | 241 (53%) | 320 (50%) | 0.50 |

| Asymmetric motor weakness | 39 (44%) | 219 (48%) | 243 (38%) | 0.002 |

| Herniation type | <0.001 | |||

| Protruding | 15 (17%) | 119 (26%) | 188 (29%) | |

| Extruded | 54 (61%) | 309 (68%) | 419 (65%) | |

| Sequestered | 19 (22%) | 28 (6%) | 39 (6%) | |

| Posterolateral herniation | 39 (44%) | 345 (76%) | 534 (83%) | <0.001 |

Includes only patients who had follow-up data available for the two-year outcomes analysis.

P values are based on chi-square tests for categorical variables and on analysis of variance for continuous variables.

The values are given as the mean and the standard deviation.

Seventy-two percent (465) of 646 patients with L5-S1 herniations and 57% (262) of 456 with L4-L5 herniations had a positive ipsilateral straight leg-raising test, while 43% (thirty-eight) of eighty-eight patients with upper level herniations had a positive femoral stretch test. The patients with upper level herniations and L4-L5 herniations were less likely to have asymmetric reflexes, while those with L5-S1 herniations were less likely to have motor weakness. Upper level herniations were more likely to be foraminal (24% of upper level herniations, 3% of L4-L5 herniations, 2% of L5-S1 herniations; p < 0.001) and far lateral (25% of upper level herniations, 7% of L4-L5 herniations, and 6% of L5-S1 herniations; p < 0.001), rather than posterolateral herniations (44% of upper level herniations, 76% of L4-L5 herniations, and 83% of L5-S1 herniations; p < 0.001). The upper level herniation group was more likely to have a sequestered fragment.

Nonoperative Treatments

Nonoperative treatments used for 546 patients (415 managed nonoperatively and 131 surgical patients with data on nonoperative care at follow-up visits prior to a second operation) included education and counseling (92%; 505 patients), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (59%; 323 patients), epidural injections (48%; 264 patients), physical therapy (43%; 237 patients), and narcotic pain medication (41%; 224 patients)4,5.

Operative Treatments and Complications

The mean operative time was less for the treatment of L5-S1 herniations (71.4 minutes) than for L4-L5 (82.0 minutes) and upper level herniations (81.7 minutes) (p < 0.001). Surgical complications varied slightly between groups and are shown in Table II, but no differences were significant on the basis of the numbers. Blood loss was slightly larger in operations on upper level herniations than in operations on the lower levels. The L4-L5 group had the greatest number of durotomies (4%) among the three groups.

TABLE II.

Operative Treatments, Complications, and Events

| L2-L3 and L3-L4 (N = 42) | L4-L5 (N = 299) | L5-S1 (N = 432) | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operation time†(min) | 81.7 ± 36.2 | 82 ± 40.2 | 71.4 ± 32.1 | <0.001 |

| Blood loss†(mL) | 78.7 ± 76.1 | 72.6 ± 113.1 | 56 ± 90.9 | 0.053 |

| Intraoperative complications‡(no. of patients) | ||||

| Dural tear and/or spinal fluid leak | 1 (2%) | 12 (4%) | 10 (2%) | 0.40 |

| Nerve root injury | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.45 |

| Vascular injury | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.68 |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 2 (0%) | 0.89 |

| None | 40 (98%) | 285 (96%) | 419 (97%) | 0.58 |

| Postoperative complications or events§(no. of patients) | ||||

| Nerve root injury | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.68 |

| Wound hematoma | 1 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 1 (0%) | 0.15 |

| Superficial wound infection | 1 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 9 (2%) | 0.51 |

| Deep wound infection | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0.87 |

| Other | 3 (7%) | 7 (2%) | 17 (4%) | 0.21 |

| None | 37 (90%) | 282 (96%) | 401 (93%) | 0.23 |

The p value is for the comparison across all three groups with use of analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

The values are given as the mean and the standard deviation.

Data were not available for one patient with upper level herniation and for three patients with L4-L5 herniation. No instances of aspiration or operation at the wrong level were reported.

Any reported complications up to eight weeks postoperatively. No instances of blood transfusion, cerebrospinal fluid leak, paralysis, cauda equina injury, or wound dehiscence were reported.

Main Treatment Effects

The main treatment outcomes analyzed with use of the adjusted change scores and treatment effects (improvement in operative group minus improvement in nonoperative group), according to the treatment received for each herniation group, are shown in Table III. At all levels, the group treated operatively had greater improvement than the group treated nonoperatively at the three-month evaluation and it persisted at the two-year evaluation. While the treatment effects at three months were similar across all levels, the groups diverged at later time points. At two years, the mean treatment effects (and 95% confidence intervals) at upper lumbar levels were significantly better than at the L5-S1 level for all outcome measures (Table IV). The treatment effect was somewhat greater for the L4-L5 herniations than for L5-S1 herniations, which was significant for physical functioning (p = 0.006) and borderline significant for bodily pain (p = 0.073) and Oswestry Disability Index (p = 0.073) (Figs. 2 and 3). Treatment effects for the upper lumbar levels were greater than at L4-L5 for all measures, but were significant only for bodily pain (p = 0.018). The differences in treatment effect appeared to result from greater improvement with nonoperative treatment for the lower level herniations, as well as a slightly better operative outcome for the upper level herniations.

TABLE III.

Adjusted Change Scores and Treatment Effects for the Intervertebral Disc Herniation Randomized and Observational Cohorts According to Treatment Received and Herniation Level*

| Baseline

|

3-Mo Evaluation

|

1-Yr Evaluation

|

2-Yr Evaluation

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group According to Herniation Level | Op. Treatment | Nonop. Treatment | Overall | Op. Treatment | Nonop. Treatment | Treatment Effect† (95% Confidence Interval) | Op. Treatment | Nonop. Treatment | Treatment Effect† (95% Confidence Interval) | Op. Treatment | Nonop. Treatment | Treatment Effect† (95% Confidence Interval) |

| L2-L3 and L3-L4 | ||||||||||||

| No. of patients | 41 | 53 | 35 | 45 | 36 | 45 | 37 | 42 | ||||

| SF-36 bodily pain‡ | 27.8 (2.7) | 30.1 (2.6) | 29.1 (1.9) | 39.8 (4) | 20.5 (3.5) | 19.3 (8.1, 30.4) | 48.8 (4.2) | 24.3 (3.5) | 24.5 (13, 36) | 49 (4.0) | 24.4 (3.6) | 24.6 (13.2, 36) |

| SF-36 physical functioning‡ | 33.4 (3.4) | 36.3 (3.2) | 35.0 (2.3) | 38.2 (4.1) | 20.6 (3.6) | 17.6 (6.4, 28.9) | 45.7 (4.2) | 21.7 (3.6) | 24 (12.4, 35.7) | 48 (4.1) | 24.6 (3.6) | 23.4 (11.9, 34.9) |

| Oswestry Disability Index‡ | 51.0 (3.0) | 43.5 (2.8) | 46.8 (2.1) | −31.9 (3.1) | −18.3 (2.8) | −13.6 (−22.1, −5.1) | −36.3 (3.2) | −16.6 (2.8) | −19.7 (−28.6, −10.8) | −38.3 (3.1) | −19.3 (2.8) | −19 (−27.7, −10.2) |

| L4-L5 | ||||||||||||

| No. of patients | 300 | 225 | 272 | 165 | 254 | 138 | 254 | 129 | ||||

| SF-36 bodily pain‡ | 21.9 (1) | 32.4 (1.3) | 26.4 (0.9) | 43.7 (1.4) | 25.6 (1.7) | 18.1 (13.9, 22.3) | 44.9 (1.4) | 31.4 (1.8) | 13.6 (9.1, 18) | 43.1 (1.4) | 31.6 (1.9) | 11.6 (7, 16.1) |

| SF-36 physical functioning‡ | 31.2 (1.4) | 46.6 (1.7) | 37.8 (1.1) | 45.1 (1.3) | 25.5 (1.6) | 19.6 (15.7, 23.6) | 46.2 (1.3) | 28.8 (1.7) | 17.4 (13.2, 21.6) | 45.7 (1.3) | 28.6 (1.8) | 17.1 (12.8, 21.4) |

| Oswestry Disability Index‡ | 57.0 (1.2) | 40.6 (1.4) | 50.0 (1) | −38.3 (1.1) | −23.4 (1.4) | −14.9 (−18.1, −11.6) | −39.6 (1.1) | −25 (1.5) | −14.6 (−18.1, −11.1) | −38.5 (1.1) | −24.7 (1.5) | −13.8 (−17.3, −10.3) |

| L5-S1 | ||||||||||||

| No. of patients | 434 | 334 | 393 | 222 | 361 | 191 | 355 | 171 | ||||

| SF-36 bodily pain‡ | 23.1 (0.8) | 30 (1.0) | 26.1 (0.6) | 39.7 (1.2) | 23.4 (1.5) | 16.4 (12.8, 20) | 42 (1.2) | 31.5 (1.6) | 10.6 (6.7, 14.4) | 41.7 (1.2) | 34.6 (1.7) | 7.1 (3.1, 11.1) |

| SF-36 physical functioning‡ | 31.9 (1.1) | 45.6 (1.4) | 37.9 (0.9) | 38.3 (1.1) | 21.5 (1.4) | 16.8 (13.4, 20.2) | 43.7 (1.1) | 29.2 (1.5) | 14.5 (10.9, 18.1) | 42.4 (1.1) | 32.5 (1.6) | 9.9 (6.2, 13.6) |

| Oswestry Disability Index‡ | 55.3 (0.9) | 41.9 (1.1) | 49.5 (0.8) | −34.9 (0.9) | −18.1 (1.2) | −16.8 (−19.6, −14) | −36.5 (0.9) | −23.2 (1.3) | −13.4 (−16.4, −10.4) | −36.2 (0.9) | −26 (1.3) | −10.3 (−13.4, −7.2) |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, work status, disability compensation status, body mass index, smoking, joint problems, migraine headaches, any neurological deficit, herniation (type and location), baseline score, baseline leg-symptom severity, baseline satisfaction with symptoms, self-rated health trend, center, and insurance.

Treatment effect is defined as the change in the operative group minus the change in the nonoperative group. A moving baseline was used, with the clock reset at the time of surgery for any patient having surgery.

The operative and nonoperative values are given as the mean score with the standard error of the mean in parentheses. Each scale ranged from 0 to 100. SF-36 = Short Form-36.

TABLE IV.

Two-Year Treatment Effects by Disc Herniation Level*

| Treatment Effect

|

Comparison of Herniation Levels (p value)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Level Herniation (N = 88) | L4-L5 (N = 455) | L5-S1 (N = 643) | Upper Levels and L4-L5 | Upper Levels and L5-S1 | L4-L5 and L5-S1 | |

| SF-36 bodily pain score | 24.6 (13.2, 36) | 11.6 (7, 16.1) | 7.1 (3.1, 11.1) | 0.018 | 0.002 | 0.073 |

| SF-36 physical functioning score | 23.4 (11.9, 34.9) | 17.1 (12.8, 21.4) | 9.9 (6.2, 13.6) | 0.16 | 0.014 | 0.006 |

| Oswestry Disability Index | −19 (−27.7, −10.2) | −13.8 (−17.3, −10.3) | −10.3 (−13.4, −7.2) | 0.14 | 0.033 | 0.073 |

Treatment effect is defined as the change in the operative group minus the change in the nonoperative group. As-treated randomized and observational cohorts combined, adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, work status, disability compensation status, body mass index, smoking, joint problems, migraines, any neurological deficit, herniation (type and location), baseline score, baseline leg-symptom severity, baseline satisfaction with symptoms, self-rated health trend, center, and insurance. Upper level herniations are at L2-L3 and L3-L4. SF-36 = Short Form-36.

Fig. 2.

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) bodily pain treatment effects. The data points represent the differences in the change of bodily pain scores between the operative and nonoperative groups at each follow-up time period (that is, the improvement in the operative group minus the improvement in the nonoperative group). The vertical bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Fig. 3.

Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) treatment effects. The data points represent the differences in the change of ODI scores between the operative and nonoperative groups at each follow-up time period (that is, the improvement in the operative group minus the improvement in the nonoperative group). The vertical bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Our data showed that, following lumbar discectomy, patients had a greater difference in improvement between operative and nonoperative treatment for upper level herniations (L2-L3 and L3-L4) than for herniations at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels. Patients with the upper level herniations had less improvement with nonoperative treatment and slightly better operative outcomes than those with lower level herniations. The magnitude of the difference between the upper level herniations and herniations at L5-S1 was in the range of 10 to 15 points on the SF-36 bodily pain and physical functioning scales and the Oswestry Disability Index. This is in the range that is generally considered to be clinically important and the size of effect that the overall SPORT was powered to detect5. Some of these comparisons were significant; however, the size of the group with upper level herniations was modest, limiting the statistical power. Furthermore, the effect was highly consistent with a monotonic (dose-response-like) relationship between level and outcome (upper level herniation results were greater than the L4-L5 results, which were greater than the L5-S1 results), which was consistent at both one and two years and was similar across all three primary dimensions of outcome, i.e., pain, function, and disability. This consistent pattern lends strength to the inference that herniation level has a significant effect on outcome.

Similar to the results reported by Osterman et al., surgery for herniations affecting the L4-L5 disc had a greater treatment effect than did surgery for L5-S1 lesions2. However, our results showed a significant treatment effect for surgery at L5-S1 (p < 0.001), a finding not evident in the report by Osterman et al. This may be related to the substantially larger sample size in the current study. Our results are consistent with the conclusion by Spangfort that the upper level herniations have better relief of radicular symptoms than do the lower levels9.

There are several possible explanations for these findings. A number of studies have shown that reduced spinal canal cross-sectional area is associated with an increased probability of symptomatic disc herniation and greater intensity of herniation symptoms19. The spinal cross-sectional area is the smallest at the most cranial lumbar segment and increases caudally19. The smaller canal area at upper levels may contribute to the observed outcomes differences, but further analysis comparing outcomes to cross-sectional area is required.

The location of the disc herniation (foraminal compared with posterolateral compared with central) may also contribute to these differences. In this study, upper lumbar herniations were more likely to occur in the far lateral and foraminal positions than were those at the lower two intervertebral levels. This finding is similar to the observation by Tamir et al., in a study of eighty-nine patients, which suggested upper level herniations are less likely to be posterolateral and are more commonly in the far lateral or foraminal positions11. It is possible that an increased number of far lateral herniations partially contributed to the difference in outcomes, although again this was controlled for in the analysis.

A prior retrospective cohort study of sixty-nine upper lumbar herniations by Sanderson et al. found that they had worse surgical outcomes than lower level herniations20. However, methodological limitations in that study may account for the different outcomes observed. Those authors included a high proportion of reoperations and arthrodeses at the higher levels, which likely contributed to their poorer surgical outcomes. Furthermore, they had no control group, and we found that worse nonoperative outcome among those with an upper lumbar herniation was a major contributor to the improved treatment effect.

There are a number of limitations to our study. The level of disc herniation was based on the clinician report after evaluation of the magnetic resonance imaging studies. Transitional vertebrae of the lumbar spine are identified in 5% to 20% of lumbar radiographs6,21-23. Since imaging occasionally did not include the first non-rib-bearing vertebrae, it is possible that some levels were categorized incorrectly. Far lateral herniations may have contributed to misclassifications, as extraforaminal connections are sometimes found between the L3, L4, and L5 nerve roots, which may cause a mixed presentation of neurological signs and symptoms. Perhaps more importantly, like any subgroup analysis, the study was not powered to assess differences between groups, and the upper lumbar herniation group was relatively small. The results of these subgroup comparisons may also be confounded by unmeasured differences between the groups.

Overall, analysis of the SPORT disc herniation cohort showed that, in as-treated analyses, both the patients managed operatively and those managed nonoperatively had considerable improvement over two years, but that the discectomy group reported better outcomes. In this subgroup analysis, these results seem to hold regardless of herniation level; however, the relative advantage for surgery was greater for patients with herniations at higher lumbar levels, with nonoperative treatment being less effective in these patients compared with those with herniations at L4-L5 and L5-S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Note: This study is dedicated to the memory of Brieanna Weinstein.

Disclosure: In support of their research for or preparation of this work, one or more of the authors received, in any one year, outside funding or grants in excess of $10,000 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS; U01-AR45444-01A1) and the Office of Research on Women's Health, the National Institutes of Health; and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center in Musculoskeletal Diseases is funded by NIAMS (P60-AR048094-01A1), and one author received a Research Career Award from NIAMS (1 K23 AR 048138-01). Neither they nor a member of their immediate families received payments or other benefits or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from a commercial entity. No commercial entity paid or directed, or agreed to pay or direct, any benefits to any research fund, foundation, division, center, clinical practice, or other charitable or nonprofit organization with which the authors, or a member of their immediate families, are affiliated or associated.

A commentary is available with the electronic versions of this article, on our web site (www.jbjs.org) and on our quarterly CD-ROM/DVD (call our subscription department, at 781-449-9780, to order the CD-ROM or DVD).

Investigation performed at the Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire

References

- 1.Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Wu YA, Deyo RA, Singer DE. Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of sciatica secondary to a lumbar disc herniation: 10 year results from the Maine Lumbar Spine Study. Spine. 2005;30:927-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osterman H, Seitsalo S, Karppinen J, Malmivaara A. Effectiveness of microdiscectomy for lumbar disc herniation: a randomized controlled trial with 2 years of follow-up. Spine. 2006;31:2409-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber H. Lumbar disc herniation. A controlled, prospective study with ten years of observation. Spine. 1983;8:131-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Skinner JS, Hanscom B, Tosteson AN, Herkowitz H, Fischgrund J, Cammisa FP, Albert T, Deyo RA. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort. JAMA. 2006;296:2451-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson AN, Hanscom B, Skinner JS, Abdu WA, Hilibrand AS, Boden SD, Deyo RA. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2441-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson GBJ. The epidemiology of spinal disorders. In: Frymoyer JW, editor. The adult spine: principles and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. p 127.

- 7.Dammers R, Koehler PJ. Lumbar disc herniation: level increases with age. Surgical Neurol. 2002;58:209-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu K, Zucherman J, Shea W, Kaiser J, White A, Schofferman J, Amelon C. High lumbar disc degeneration. Incidence and etiology. Spine. 1990;15:679-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spangfort EV. The lumbar disc herniation. A computer-aided analysis of 2,504 operations. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1972;142:1-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albert TJ, Balderston RA, Heller JG, Herkowitz HN, Garfin SR, Tomany K, An HS, Simeone FA. Upper lumbar disc herniations. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamir E, Anekshtein Y, Melamed E, Halperin N, Mirovsky Y. Clinical presentation and anatomic position of L3-L4 disc herniation: a prospective and comparative study. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17:467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber H. Lumbar disc herniation. A prospective study of prognostic factors including a controlled trial. J Oslo City Hosp. 1978;28:89-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frymoyer JW, Hanley EN Jr, Howe J, Kuhlmann D, Matteri RE. A comparison of radiographic findings in fusion and nonfusion patients ten or more years following lumbar disc surgery. Spine. 1979;4:435-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurme M, Alaranta H. Factors predicting the result of surgery for lumbar intervertebral disc herniation. Spine. 1987;12:933-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fardon DF, Milette PC; Combined Task Forces of the North American Spine Society, American Society of Spine Radiology, and American Society of Neuroradiology. Nomenclature and classification of lumbar disc pathology. Recommendations of the Combined Task Forces of the North American Spine Society, American Society of Spine Radiology, and American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine. 2001;26:E93-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Zegler SL. The analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002.

- 17.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daltroy LH, Cats-Baril WL, Katz JN, Fossel AH, Liang MH. The North American Spine Society lumbar spine outcome assessment Instrument: reliability and validity tests. Spine. 1996;21:741-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dora C, Wälchli B, Elfering A, Gal I, Weishaupt D, Boos N. The significance of spinal canal dimensions in discriminating symptomatic from asymptomatic disc herniations. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:575-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanderson SP, Houten J, Errico T, Forshaw D, Bauman J, Cooper PR. The unique characteristics of “upper” lumbar disc herniations. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otani K, Konno S, Kikuchi S. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae and nerve-root symptoms. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:1137-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tini PG, Wieser C, Zinn WM. The transitional vertebra of the lumbosacral spine: its radiological classification, incidence, prevalence, and clinical significance. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1977;16:180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vergauwen S, Parizel PM, van Breusegem L, Van Goethem JW, Nackaerts Y, Van den Hauwe L, De Schepper AM. Distribution and incidence of degenerative spine changes in patients with a lumbo-sacral transitional vertebra. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:168-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.