Abstract

GOALS:

To determine whether the perceived impact of ulcerative colitis (UC) on activities of living (illness intrusiveness) is greater for people who are not living in a married or common-law relationship.

BACKGROUND:

In general, social and occupational achievement is not greatly impaired by UC, yet patients, especially young adults, often have interpersonal concerns.

METHODS:

One hundred fifty-five outpatients with UC were assessed for disease activity, and completed self-reports of marital status, income, social support and illness intrusiveness.

RESULTS:

Fifty-one patients (32.9%) were single, separated or divorced, and 104 patients (67.1%) were married or in common-law relationships. Compared with those who were married or in common-law relationships, single or separated patients were younger, had a lower household income, had lived with UC for fewer years and were less satisfied with social support. Among 135 patients in remission, marital status was significantly associated with illness intrusiveness, controlling for age, income and perceived social support (F=5.73; P=0.02). Low social support (F=4.94; P=0.03) and younger age (F=7.24; P=0.008) were independently associated with illness intrusiveness. Single patients in remission reported illness intrusiveness of similar severity to that reported by patients with active disease.

CONCLUSIONS:

The perceived impact of UC on the lives of patients is greater in those who are not married or living in common-law relationships. Youth, single status and lower social support commonly coexist, and exert additive effects on the functional impact of UC. Resources to improve social support should be directed toward this group of patients.

Keywords: Marital status, Quality of life, Social support, Ulcerative colitis

Abstract

OBJECTIFS :

Déterminer si les répercussions perçues de la colite ulcéreuse (CU) sur les activités de la vie (intrusion de la maladie) sont plus marquées pour les personnes qui ne sont pas mariées ou conjointes de fait.

HISTORIQUE :

En général, la CU n’a pas tellement d’incidence sur les réalisations sociales et professionnelles, mais les patients, notamment les jeunes adultes, ont souvent des problèmes interpersonnels.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les auteurs ont évalué l’activité de la maladie de 155 patients atteints de CU vus en consultations externes et leur ont fait remplir une autoévaluation sur leur état matrimonial, leur revenu, leur soutien social et l’intrusion de la maladie.

RÉSULTATS :

Cinquante et un patients (32,9 %) étaient célibataires, séparés ou divorcés, et 104 (67,1 %) étaient mariés ou conjoints de fait. Par rapport à ceux qui étaient mariés ou conjoints de fait, les patients célibataires ou séparés étaient plus jeunes, avaient un revenu du ménage moins élevé, vivaient avec la CU depuis moins longtemps et étaient moins satisfaits par leur soutien social. Chez les 135 patients en rémission, l’état matrimonial s’associait de manière significative à l’intrusion de la maladie, au contrôle par rapport à l’âge, au revenu et au soutien social perçu (F=5,73; P=0,02), Le peu de soutien social (F=4,94; P=0,03) et le plus jeune âge (F=7,24; P=0,008) étaient reliés de manière indépendante à l’intrusion de la maladie. Les patients célibataires en rémission déclaraient une intrusion de la maladie tout aussi grave que ceux qui étaient atteints d’une maladie active.

CONCLUSIONS :

Les répercussions perçues de la CU sur la vie des patients sont plus élevées chez ceux qui ne sont pas mariés ou conjoints de fait. Le jeune âge coexiste souvent avec le célibat et un faible soutien social, ce qui a des effets supplémentaires sur les répercussions fonctionnelles de la CU. Il faudrait orienter des ressources vers ce groupe de patients en vue d’améliorer leur soutien social.

Interpersonal relationships may play an important role in the course of illness for a person with ulcerative colitis (UC). The experience of living with UC involves major interpersonal challenges, including living with stigmatizing bowel symptoms, finding a balance between accepting needed support from friends and family and risking feeling like a burden, and maintaining effective relationships with doctors and other health care providers. In clinical practice, people with UC often report concerns about the actual or potential effects that the disease has on interpersonal activity and relationships. For example, it is common for patients to report that they hesitate to accept social invitations because of an uncertainty about their wellness from day to day. Furthermore, UC patients who are not in a stable, long-term relationship often indicate concerns about their ability to attract a partner, and about when and how to tell a potential partner about their illness. However, while these concerns are recorded in clinical and anecdotal accounts of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (1,2), objective indicators of social development and activity, including the percentage of people who marry, the frequency of family problems and the frequency of sexual activity, are reported to be similar in UC patients and healthy adults (3,4). A population-based survey (5) in Canada found that people with IBD were more likely than the general population to be married.

Subjective concerns have been measured with “The rating form of IBD patient concerns” (6). Although several of the concerns in this instrument have an interpersonal component, being a burden was the only interpersonal concern to be rated among the top 10 concerns in large studies in the United States (6) and eight other countries (7). Thus, while the interpersonal or social impact of UC may be important to many individuals, on average, it is less of a concern to those living with the disease than medication, disease uncertainty and surgery, for example.

A complementary approach to understanding the link between personal relationships and disease impact is to determine whether UC has a different impact on patients who live in different social circumstances. It has long been recognized that social support, especially support from a partner or from close confidantes, buffers stress and has a positive impact on many functional and biological consequences of disease (8,9). Being in a committed partnership, marriage or common-law relationship is associated with a better prognosis than being single, separated or widowed in several medical circumstances (10–13). Mechanisms by which having a partner may reduce the burden of living with UC include providing emotional support, sharing the burden of household tasks, providing other types of practical support and sharing financial resources.

We hypothesized that UC interferes more in the lives of patients who do not have a marital or common-law partner. Because it is expected that patients without a partner are younger, on average, than those in a committed partnership, and have a lower total household income and less social support, we also determined the extent to which those factors affected the burden of illness. Finally, we explored which domains of illness burden were the most sensitive to marital status.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The methods of subject recruitment for the present study have been previously described (14). Patients who had had a colectomy or cardiovascular disease (exclusion criteria for an aspect of the study not reported here) were excluded. Participation required three visits: an assessment by a gastroenterologist, which included a history, physical examination, endoscopy and blood collection; completion of a self-report of UC symptoms and psychological surveys; and a half-day in a stress laboratory to measure psychological and physiological variables that have been reported elsewhere (15). Subjects were paid $90. Forty-four per cent of the eligible subjects who were contacted by telephone (n=158) consented to participation in the study. Three subjects were removed from the analysis because of missing data. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Boards of Mount Sinai Hospital (Toronto, Ontario) and the University Health Network.

Evaluations

Demographic and socioeconomic information was surveyed by self-report with a questionnaire. UC disease activity was measured using the St Mark’s Index (16), which grades general health, abdominal pain, bowel frequency, stool consistency, blood in stool, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, abdominal tenderness, extraintestinal manifestations, fever and sigmoidoscopic appearance, generating a summary index of severity with scores ranging from 0 to 22.

The disruptive effects of living with UC were measured using the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale (17), which quantifies illness-induced disruptions to lifestyle, activities and interests that can compromise psychosocial well-being in chronic disease. Using a seven-point Likert scale, patients rated the degree to which illness had interfered with 13 domains of experience: health, diet, work, active recreation, passive recreation, financial situation, partner relationships, sex life, family relations, other social relations, self-expression and self-improvement, religious expression, and community and civic involvement. The factor structure and reliability of the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale has been demonstrated in several chronic disease populations (18,19), and further studies (20–22) have demonstrated that illness intrusiveness is sensitive to personal context and mediates quality of life in chronic illness.

Perceived social support was measured using the short form of the Social Support Questionnaire (23,24). This instrument measures both the size of a person’s support network and the perceived quality of support. For each of the six domains of support (eg, “Who can you really count on to be dependable when you need help?”), respondents indicated the number of people who provided this type of support (zero to nine people) and then rated their satisfaction with the support received using a six-point scale. Network size and satisfaction scores were the respective means for six items.

Statistical analysis

Demographic variables, disease indexes and psychological variables were compared between groups defined by marital status using the T test or the χ2 test. Perceived social support scores were skewed toward high scores, resulting in a ceiling effect (more than 30% of subjects reported satisfaction at the highest possible score of 6.0), so that the scores were recoded into ordinal variables (1 – score of less than 5.0; 2 – score of 5.0 to 5.9; 3 – score equal to 6.0).

The relationship between marital status and illness intrusiveness was tested using ANOVA. Because the presence of active colitis was expected to strongly influence illness intrusiveness, patients with and without objective findings of currently active inflammation (ie, abdominal tenderness, extraintestinal manifestations, fever or visible inflammation at sigmoidoscopy) were analyzed separately. Age, income level and perceived social support were entered into the ANOVA as covariates. The direction of significant relationships was determined by post hoc testing. Finally, to explore the relationship between the 13 domains of illness intrusiveness and marital status, a multivariate ANOVA was performed, with the three subject groups as the dependent variable, and age, income level and perceived social support as the covariates.

Significance was set at P<0.05 (two-tailed). Analysis was performed using SSPS 13.0 (SPSS Inc, USA).

RESULTS

One hundred fifty-five patients with UC participated. Of those patients, 51 (32.9%) were single (n=39), or separated or divorced (n=12); and 104 patients (67.1%) were married or in common-law relationships. No participants were widowed. The distribution of sex was not significantly different in single or separated patients (52.9% women) from married or common-law patients (39.4% women; P=0.11). Endoscopically visible mucosal inflammation occurred more frequently in single or separated patients (37.5%) than in married or common-law patients (21.6%; P=0.043) and the mean UC disease activity score was higher in single or separated patients (mean ± SD St Mark’s Index score 3.14±2.96) than in married or common-law patients (1.71±2.38; P=0.002). Compared with patients who were married or in common-law relationships, single or separated patients were younger, had a lower household income and had lived with UC for fewer years (Table 1). Single or separated UC patients reported a similar number of individuals in their lives who provided emotional support, but reported a significantly lower satisfaction with the support that was provided, than UC patients who were living in married or common-law relationships (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

The association of marital status with demographic and socioeconomic indexes, as well as disease duration in 155 outpatients with ulcerative colitis

| Variable | Single or separated patients (n=51), % | Married or common-law patients (n=104), % | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| 18 to 29 | 45.1 | 1.9 | |

| 30 to 39 | 23.6 | 28.8 | |

| 40 to 49 | 17.6 | 33.7 | |

| 50 and older | 13.7 | 35.6 | <0.001 |

| Total annual household income | |||

| Less than $30,000 | 35.3 | 3.9 | |

| $30,000 to $49,999 | 33.3 | 36.3 | |

| $50,000 to $99,999 | 19.6 | 7.8 | |

| $100,000 or more | 11.8 | 52.0 | <0.001 |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 6.0 | 7.8 | |

| High school graduate | 30.0 | 22.6 | |

| Postsecondary | 64.0 | 69.6 | 0.59 |

| Work status | |||

| Full-time student or employment | 72.6 | 64.1 | |

| Less than full-time by choice | 13.7 | 27.2 | |

| Less than full-time due to illness or other | 13.7 | 8.7 | 0.14 |

| Duration of ulcerative colitis, years | |||

| 0 to 5 | 25.5 | 11.6 | |

| 6 to 10 | 39.2 | 22.1 | |

| 11 to 15 | 15.7 | 22.1 | |

| 16 and more | 19.6 | 44.2 | 0.003 |

TABLE 2.

The association of marital status with self-reported social support in outpatients with ulcerative colitis

| Variable | Single or separated patients (n=51), % | Married or common-law patients (n=101), % | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people providing support | |||

| <2 | 26.4 | 18.6 | |

| 2–3 | 28.3 | 31.4 | |

| >3 | 45.3 | 50.0 | 0.61 |

| Satisfaction with support (score) | |||

| Low (<5) | 39.2 | 18.8 | |

| Moderate (5–5.9) | 45.1 | 43.6 | |

| High (6) | 15.7 | 30.3 | 0.004 |

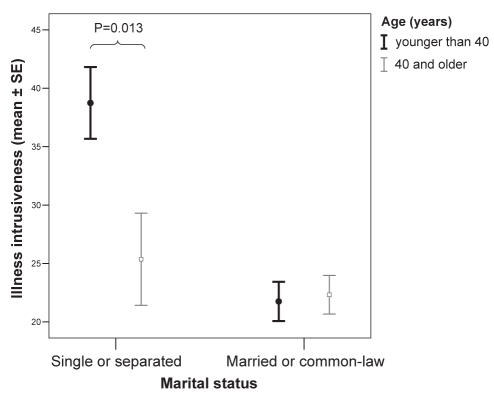

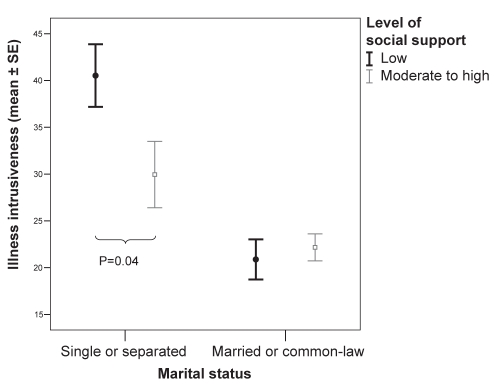

Twenty patients had active UC at the time of assessment. This group was too small to allow analysis of the correlates of marital status in active disease. Among the 135 patients in remission (39 single or separated patients, and 96 married or common-law patients), being single or separated was significantly associated with illness intrusiveness, controlling for age and perceived social support (Table 3). Income level was not significantly associated with illness intrusiveness and was removed from the ANOVA to optimize the degrees of freedom. Post hoc testing revealed that illness intrusiveness was higher in single or separated patients (mean score 34.3) than in married or common-law patients (mean score 22.1). For patients with active UC, the mean illness intrusiveness score was 40.5. Younger age was associated with greater illness intrusiveness, particularly in single or separated patients (Figure 1). The relationship of social support with illness intrusiveness did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07), although, as shown in Figure 2, low social support was associated with higher illness intrusiveness in single or separated UC patients.

TABLE 3.

The association of marital status with illness intrusiveness: Univariate ANOVA in ulcerative colitis patients in remission

| Variable | Degrees of freedom | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected model | 4 | 8.79 | <0.001 |

| Marital status | 1 | 8.42 | 0.004 |

| Age | 1 | 5.30 | 0.02 |

| Satisfaction with support | 2 | 2.75 | 0.07 |

R2=0.217 (Adjusted R2=0.192)

Figure 1).

The association of marital status with illness intrusiveness in 135 adult patients with ulcerative colitis in remission, categorized by age. Illness intrusiveness was greatest in those who were younger and unmarried. SE Standard error

Figure 2).

The association of marital status with illness intrusiveness in 135 adult patients with ulcerative colitis in remission, categorized by social support. Social support buffers illness intrusiveness in single or separated patients. SE Standard error

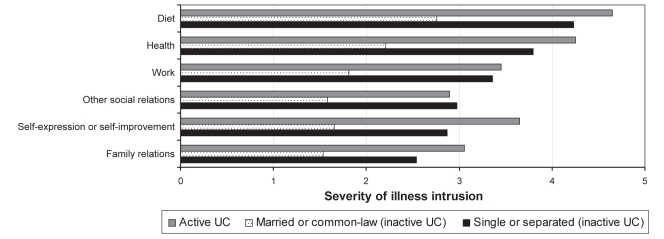

Among the participants in remission, multivariate ANOVA (correcting for age, income and perceived support) identified a significant relationship between being single or separated and six domains of illness intrusiveness (Table 4). The pattern of this relationship is shown in Figure 3. Notably, in these six domains, the intensity of illness intrusiveness in single or separated patients for patients in clinical remission was similar to that of patients with active inflammation.

TABLE 4.

The association of marital status with domains of illness intrusiveness in 135 ulcerative colitis patients in remission, corrected for age, income and perceived social support

|

Marital status, df=1 |

Age, df=1 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | F | P | F | P |

| Health | 6.62 | 0.01 | 13.97 | <0.001 |

| Diet | 8.59 | 0.004 | 3.45 | 0.07 |

| Work | 11.98 | 0.001 | 2.89 | 0.09 |

| Active recreation | 3.72 | 0.06 | 6.84 | 0.01 |

| Passive recreation | 3.00 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.73 |

| Financial situation | 2.34 | 0.13 | 3.66 | 0.06 |

| Partner relationship | 0.50 | 0.48 | 3.28 | 0.07 |

| Sex life | 0.03 | 0.87 | 1.51 | 0.22 |

| Family relations | 7.791 | 0.006 | 0.52 | 0.47 |

| Other social relations | 12.10 | 0.001 | 2.79 | 0.10 |

| Self-expression or self-improvement | 5.67 | 0.02 | 4.53 | 0.04 |

| Religious expression | 0.12 | 0.73 | 0.33 | 0.57 |

| Community and civic involvement | 0.22 | 0.64 | 6.47 | 0.01 |

| Multivariate test (Wilk’s Lambda) | F=2.70 | F=2.26 | ||

| P=0.003 | P=0.01 | |||

Results are not shown for nonsignificant relationships between domains of illness intrusiveness and income (Wilk’s Lambda F=1.30; P=0.23) and perceived support (Wilk’s Lambda F=0.93; P=0.53). df Degrees of freedom

Figure 3).

Severity of intrusion of ulcerative colitis (UC) in six domains of daily life in 135 patients with UC who were in remission, with results from 20 patients with active disease for comparison. The difference between married or common-law and single or separated patients was significant (P<0.05) for each domain shown, correcting for age, perceived social support and income

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study demonstrate that UC has a greater functional impact on the lives of patients who are not married or living in common-law relationships. Being single or separated is, not surprisingly, associated with youth, having a lower household income and lower perceived social support. In our study cohort, being single or separated was also associated with a higher incidence of active UC. However, the association between marital status and illness intrusiveness survived statistical control of each of those variables. Therefore, youth and single status, which commonly coexist, exert independent effects on the functional impact of UC. It is striking that illness intrusiveness in single or separated patients whose disease was in remission was similar to the level of illness intrusiveness reported by patients with active disease. Further study is required to determine whether low social support has a greater impact on illness intrusiveness in single UC patients based on the trend toward this interaction in the current study.

The present study did not compare the impact of single status in UC with any other chronic disease, and we do not infer that the findings of the present study are specific to UC. However, the study results can be understood in the context of the natural history of UC. In particular, our findings are consistent with observations in clinical practice that young patients with UC often report feeling isolated or limited by their illness (1). Because UC is commonly diagnosed in adolescence or early adulthood, the early years of learning to adjust to a chronic illness often occur in the midst of a developmental transition from the dependent relationships of childhood to adult independence. This is the time of life when many individuals are completing their education, initiating a career and finding a partner. Thus, the personal effect of a major illness is likely to be different for young adults than for patients who have completed these developmental challenges. Social support is an important mediator of health throughout the lifespan, and young adults without a committed partner may experience greater illness burden for three reasons. First, the transition from more dependent family relationships to adult independence may be accompanied by a transition to seek support from new sources. Second, earlier in the course of a chronic disease, patients may have a greater need for support from others than older veterans of illness. Finally, in addition to all of the other challenges of coping with illness, single patients may experience the extra burden of worrying about initiating and maintaining intimate relationships.

An important implication of our findings is that gastroenterologists involved in the management of IBD patients should be attentive to the greater functional impact that UC may have on younger, single patients. Resources and interventions that increase perceived support may be especially valuable for these patients. In addition to the support that is provided by family and friends, useful professional resources may include peer support through hospitals or through involvement with national associations for UC and Crohn’s disease (eg, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada, and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America). In such settings, support from peers of similar age and circumstance, and from older patients who have successfully navigated the early years of illness, may be helpful. Supportive physician-patient relationships are likely to be especially important for young, single patients.

It is noteworthy that the specific domains of illness intrusiveness that scored the highest (ie, the impact of UC on health, diet and work) were not interpersonal domains. This finding was consistent with earlier research on IBD concerns (6,7). While the magnitude of the interpersonal effects of UC appears to be modest, the findings of the present study suggest that interpersonal relationships are an important contextual determinant of the disease’s overall impact.

Income was not related to illness intrusiveness in the present cohort. Previous research has shown that, on average, income is not reduced for IBD patients compared with the general population (5). In our study cohort, income levels were relatively high, so the income reported by single patients, although lower than their married peers, may not have been low enough to significantly compromise their functional capacity. It may also be relevant that our study was performed in Canada, where universal access to health care reduces the barriers to optimal health care that may otherwise be imposed by a lower income.

There were certain limitations to our study design. While the sample size was sufficient to demonstrate a relationship between marital status and illness intrusiveness in patients in remission, too few patients with active disease were available in the cohort to make a similar comparison in the context of acute illness. Data were not available to distinguish between single patients living alone and single patients living with others. The study was not designed to compare the impact of single status on the intrusiveness of UC with other illnesses or with the impact of marital status on the ability to function in the general population. Finally, the participation rate (44%), which we believe is attributable to the time burden involved in participating in stress laboratory measures (not part of this analysis), may have resulted in biases in the study sample.

Previously available data suggest that patients with UC are likely to lead lives that are, on average, similar to their healthy peers with respect to social and occupational achievement. The results of our study alert clinicians to the findings that personal relationships are nonetheless important to achieve optimal adaptation to living with UC, and that young and single patients have the greatest need for support.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kelly MP. Colitis. New York: Routledge; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson WG. The Angry Gut: Coping with Colitis and Crohn’s Disease. New York: Plenum; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moody GA, Mayberry JF. Perceived sexual dysfunction amongst patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 1993;54:256–60. doi: 10.1159/000201046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendriksen C, Binder V. Social prognosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1980;281:581–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6240.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein CN, Kraut A, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N, Walld R. The relationship between inflammatory bowel disease and socioeconomic variables. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2117–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li Z, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Patrick DL. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: A new measure of health status. Psychosomatic Med. 1991;53:701–12. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levenstein S, Li Z, Almer S, et al. Cross-cultural variation in disease-related concerns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1822–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen S, editor. Social Support and Health. New York: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109:186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Veeger N, van Veldhuisen DJ. Marital status, quality of life, and clinical outcome in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2006;35:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDonald LD, Peacock JL, Anderson HR. Marital status: Association with social and economic circumstances, psychological state and outcomes of pregnancy. J Public Health Med. 1992;14:26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallo LC, Troxel WM, Matthews KA, Kuller LH. Marital status and quality in middle-aged women: Associations with levels and trajectories of cardiovascular risk factors. Health Psychol. 2003;22:453–63. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon HS, Rosenthal GE. Impact of marital status on outcomes in hospitalized patients. Evidence from an academic medical center. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:2465–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maunder RG, Greenberg GR, Hunter JJ, Lancee W, Steinhart AH, Silverberg MS. Psychobiological subtypes of ulcerative colitis: pANCA status moderates the relationship between disease activity and psychological distress. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2546–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maunder RG, Greenberg GR, Nolan RP, Lancee WJ, Steinhart AH, Hunter JJ. Autonomic response to standardized stress predicts subsequent disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:413–20. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200604000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powell-Tuck J, Brown RL, Lennard-Jones JE. A comparison of oral prednisone given as single or multiple daily doses for active proctocolitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1978;13:833–7. doi: 10.3109/00365527809182199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devins GM. Illness intrusiveness and the psychosocial impact of lifestyle disruptions in chronic life-threatening illness. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1994;1:251–63. doi: 10.1016/s1073-4449(12)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devins GM, Dion R, Pelletier LG, et al. Structure of lifestyle disruptions in chronic disease: A confirmatory factor analysis of the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale. Med Care. 2001;39:1097–104. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devins GM, Mandin H, Hons RB, et al. Illness intrusiveness and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: Comparison and stability across treatment modalities. Health Psychol. 1990;9:117–42. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devins GM. Psychologically meaningful activity, illness intrusiveness, and quality of life in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:172–4. doi: 10.1002/art.21854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devins GM, Bezjak A, Mah K, Loblaw DA, Gotowiec AP. Context moderates illness-induced lifestyle disruptions across life domains: A test of the illness intrusiveness theoretical framework in six common cancers. Psychooncology. 2006;15:221–33. doi: 10.1002/pon.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devins GM, Hunsley J, Mandin H, Taub KJ, Paul LC. The marital context of end-stage renal disease: Illness intrusiveness and perceived changes in family environment. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19:325–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02895149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR. A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoretical implications. J Soc Pers Relat. 1987;4:497–510. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarason IG, Levine HM, Basham RB, Sarason BR. Assessing social support: The Social Support Questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44:127–39. [Google Scholar]