Abstract

Thyrotoxicosis increases endogenous glucose production (EGP) and induces hepatic insulin resistance. We have recently shown that these alterations can be modulated by selective hepatic sympathetic and parasympathetic denervation, pointing to neurally mediated effects of thyroid hormone on glucose metabolism. Here, we investigated the effects of central triiodothyronine (T3) administration on EGP. We used stable isotope dilution to measure EGP before and after i.c.v. bolus infusion of T3 or vehicle in euthyroid rats. To study the role of hypothalamic preautonomic neurons, bilateral T3 microdialysis in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) was performed for 2 h. Finally, we combined T3 microdialysis in the PVN with selective hepatic sympathetic denervation to delineate the involvement of the sympathetic nervous system in the observed metabolic alterations. T3 microdialysis in the PVN increased EGP by 11 ± 4% (P = 0.020), while EGP decreased by 5 ± 8% (ns) in vehicle-treated rats (T3 vs. Veh, P = 0.030). Plasma glucose increased by 29 ± 5% (P = 0.0001) after T3 microdialysis versus 8 ± 3% in vehicle-treated rats (T3 vs. Veh, P = 0.003). Similar effects were observed after i.c.v. T3 administration. Effects of PVN T3 microdialysis were independent of plasma T3, insulin, glucagon, and corticosterone. However, selective hepatic sympathectomy completely prevented the effect of T3 microdialysis on EGP. We conclude that stimulation of T3-sensitive neurons in the PVN of euthyroid rats increases EGP via sympathetic projections to the liver, independently of circulating glucoregulatory hormones. This represents a unique central pathway for modulation of hepatic glucose metabolism by thyroid hormone.

Keywords: deiodinase, hepatic glucose metabolism, hypothalamus, microdialysis, sympathetic nervous system

Thyroid hormones are crucial regulators of metabolism, as illustrated by the profound metabolic derangements in patients with thyrotoxicosis or hypothyroidism (1). Thyrotoxicosis is associated with an increase in endogenous glucose production (EGP), hepatic insulin resistance, and concomitant hyperglycemia (1, 2). We have recently shown that selective hepatic sympathetic denervation attenuates the hyperglycemia and increased EGP during thyrotoxicosis, while selective hepatic parasympathetic denervation aggravates hepatic insulin resistance in thyrotoxic rats. By inference, the increase in EGP during thyrotoxicosis may be mediated in part by sympathetic input to the liver, while parasympathetic hepatic input may function to restrain insulin resistance during thyrotoxicosis (3).

The central nervous system is emerging as an important target for several endocrine and humoral factors in regulating metabolism. Hormones like insulin (4), estrogen (5), and corticosteroids (6) appear to use dual mechanisms to affect metabolism: that is, by direct actions in the respective target tissue and by indirect actions via the hypothalamus, in turn affecting target tissues via autonomic nervous system projections. For example, it has been convincingly shown that the suppression of EGP by central (i.e., hypothalamic) insulin administration can be largely abolished by selective hepatic vagal denervation (7, 8). The hypothalamus can also stimulate sympathetic efferent nerves to increase hepatic glucose production (9). Thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) are expressed in both the human and rat hypothalamus, showing abundant expression in the paraventricular (PVN) and arcuate nuclei (10, 11). These nuclei are both key players in the regulation of glucose metabolism via autonomic nervous system connections with the liver.

We hypothesized that triiodothyronine (T3) may increase EGP via a neural route from the hypothalamus to the liver. To explore this hypothesis, we investigated whether the increased EGP and hyperglycemia observed earlier during systemic thyrotoxicosis could be established by inducing “central thyrotoxicosis” in peripherally euthyroid animals. In addition, we studied the possible involvement of the hypothalamic PVN and the sympathetic outflow to the liver in the metabolic effects of central T3. We are unique in demonstrating that upon selective administration to the PVN, T3 increases EGP and plasma glucose, and that these hypothalamic T3 effects are mediated via sympathetic projections to the liver.

Results

In Experiment #1, we infused euthyroid rats treated with methimazole and T4 from an osmotic minipump (so-called “block and replacement treatment”) with either i.c.v. T3 (n = 8) or vehicle (Veh, n = 7). In Experiment #2, we administered T3 or vehicle in the hypothalamic PVN via bilateral microdialysis (MD), such as retro-dialysis (Veh MD, n = 7 vs. T3 MD, n = 9). In Experiment #3 we performed PVN T3 MD in surgically hepatic sympatectomized (HSx) animals (T3 MD HSx, n = 8) and sham-denervated animals (T3 MD Sham, n = 6).

At the time of central T3 administration, animals weighed between 320 and 360 grams. In all experimental groups, body weight increased during the last 3 days preceding central T3 administration, indicating adequate recovery from surgery and a positive energy balance. There was no difference in mean body weight of the treatment groups at time of central T3 administration in any of the experiments described.

Experiment #1: i.c.v. T3 Infusion.

The i.c.v. T3-infused animals consumed an equal amount of food as compared with i.c.v. Veh-infused rats during the 24 h following i.c.v. infusion (14.0 ± 1.8 vs. 13.6 ± 1.2 g, respectively). Nevertheless, i.c.v. T3-infused animals lost weight in this time period as compared with i.c.v. Veh-treated rats (−3.0 ± 0.6 vs. –1.1 ± 0.4% of body weight, respectively, P = 0.028).

Glucose, Glucose Kinetics, Glucoregulatory Hormones.

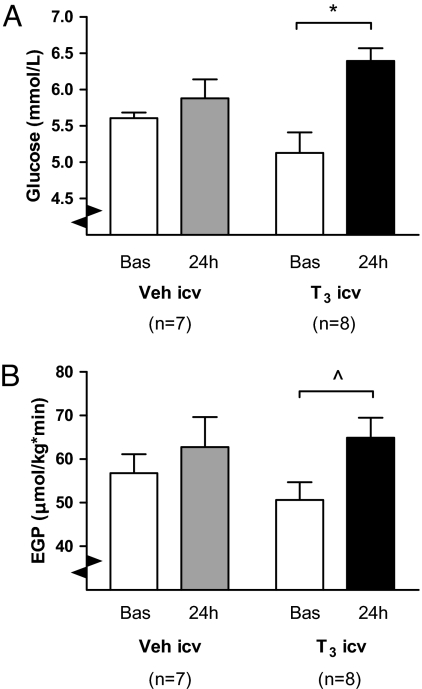

Mean basal-glucose concentrations were not significantly different between Veh i.c.v. and T3 i.c.v. groups (P = 0.148) (Fig. 1A). Basal EGP was also similar between Veh and T3-treated groups (P = 0.301) (Fig. 1B). At 24 h after i.c.v. T3 infusion, there was a significant (P = 0.027) increase in plasma glucose (28 ± 8%), compared with a nonsignificant 5 ± 4% increase in Veh-treated rats (see Fig. 1A). ANOVA revealed a trend (P = 0.062) for an increase in EGP in time, but no time*group effect. When analyzed separately, the EGP increase 24 h after i.c.v. T3 infusion almost reached significance as compared to the basal state (P = 0.057), but not so in Veh-treated rats (P = 0.482) (see Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

(A) Mean plasma glucose concentration in i.c.v. Veh- and T3-treated animals, before (basal) and after (24 h) bolus i.c.v. infusion. Note the marked, 22% plasma glucose increase in i.c.v. T3-treated rats, whereas in Veh-treated rats there was no significant effect on plasma glucose. ANOVA indicated P = 0.003 for factor time and P = 0.032 for factor time*group. *, P < 0.01. (B) EGP before (Bas) and after (24 h) i.c.v. T3 or Veh bolus infusion. EGP tended to increase after i.c.v. T3- treated rats (*, P = 0.057), but not in i.c.v. Veh-treated animals (P = 0.482). ANOVA indicated P = 0.062 for factor time.

There were no differences in basal plasma insulin and corticosterone between the groups. In both groups, plasma insulin and corticosterone 24 h after i.c.v. infusion were not different from the basal values.

Plasma Thyroid Hormones.

Basal plasma T3, thyroxine (T4), T3/T4 ratios, and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) concentrations did not differ between the 2 treatment groups (Table 1). Surprisingly, the plasma T3 concentration in animals treated with methimazole and T4 was 18 ± 5% higher 24 h after i.c.v. T3 infusion as compared with basal values (P = 0.005). Veh-treated animals showed a nonsignificant decrease in plasma T3. By contrast, plasma T4 concentrations showed a significant 28 ± 5% decrease in i.c.v. T3-treated rats (P = 0.002) and a nonsignificant 15 ± 9% decrease in Veh-treated animals. The plasma T3/T4 ratio increased by 65 ± 7% 24 h after i.c.v. T3, whereas it did not change in Veh-treated rats (i.c.v. T3 vs. Veh, P = 0.008). Plasma TSH did not differ between groups and did not change in time. Five hours after the i.c.v. T3 infusion, there was an increase in plasma T3 to values above the reference range for euthyroid animals (i.c.v. T3 4.45 ± 0.48 nmol/L vs. i.c.v. Veh 1.32 ± 0.36 nmol/L, P < 0.0001). To replicate the effects of centrally administered T3 on glucose metabolism using a refined approach, and to identify the brain area where T3 exerts its effect on glucose metabolism, we applied T3 locally in the hypothalamus by MD in Experiment #2.

Table 1.

Plasma hormone concentrations before (Basal) and after (24 h) i.c.v. vehicle and T3 infusion

| Veh i.c.v., n = 7 |

T3 i.c.v., n = 8 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | 24 h | Basal | 24 h | |

| T3 (nmol/L) | 1.25 ± 0.19 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 1.21 ± 0.12 | 1.40 ± 0.12a |

| T4 (nmol/L) | 154 ± 13 | 128 ± 12 | 149 ± 11 | 106 ± 8a |

| T3/T4 (%) | 0.87 ± 0.18 | 0.77 ± 0.10 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 1.35 ± 0.12a |

| TSH (mU/L) | 0.37 ± 0.10 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.24 ± 0.03 |

| Insulin (pmol/L) | 290 ± 47 | 351 ± 55 | 295 ± 46 | 392 ± 67 |

| Corticosterone (ng/ml) | 78 ± 39 | 150 ± 60 | 181 ± 45 | 162 ± 49 |

aP < 0.05 vs. Basal value within the same group.

Experiment #2: T3 MD in the Hypothalamic PVN.

Glucose, Glucose Kinetics, and Glucoregulatory Hormones.

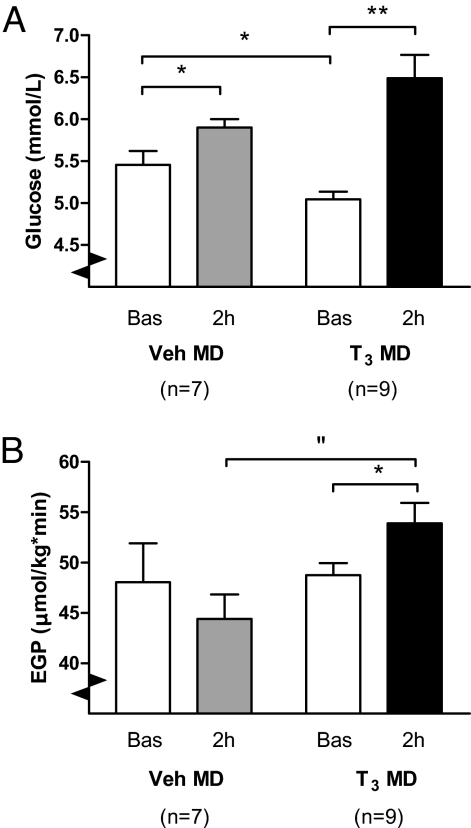

Mean basal glucose was 5.5 ± 0.2 mmol/L in Veh MD and 5.0 ± 0.1 mmol/L in T3 MD groups (P = 0.030). Mean basal EGP was not different between Veh and T3 MD groups. T3 MD induced a pronounced increase in plasma glucose concentration (Fig. 2A), which was significantly larger than that in Veh MD rats (P = 0.004) (Fig. 3A). After 2 h of Veh MD, there was a 5.1 ± 7.7% decrease in EGP. In contrast, after 2 h of T3 MD, there was a significant 10.7 ± 3.7% increase in EGP relative to basal values [ANOVA (Time*Group) P = 0.029] (Fig. 2B). The basal glucose concentration was no determinant of the plasma glucose or EGP response to T3 MD (Spearman correlation P = 0.546 and P = 0.406 for basal glucose concentration vs. relative plasma glucose and EGP increase, respectively) [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1].

Fig. 2.

(A) Mean plasma glucose concentration in intra-hypothalamic Veh (Veh MD) and T3 MD-treated rats, before (Bas) and after (2 h) MD. Note the pronounced increase of plasma glucose in T3 MD-treated rats, as compared to the mild increase in Veh MD-treated rats. ANOVA indicated P < 0.0001 for factor time and P = 0.005 for factor time*group. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.0001. (B) EGP before (Bas) and after (2 h) T3 or Veh MD in the hypothalamic PVN. Note the EGP increase after 2 h of T3 MD, in contrast to the EGP decrease in Veh Md-treated animals, with no difference in basal EGP between groups. ANOVA revealed P = 0.029 for factor time*group. “, P < 0.01, *, P < 0.05.

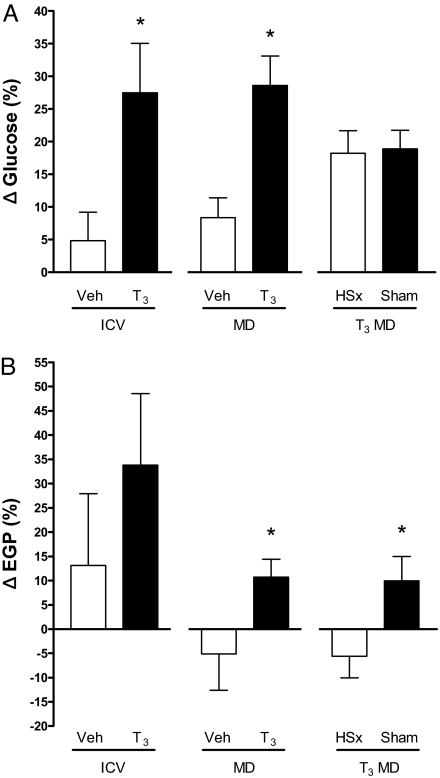

Fig. 3.

(A) Relative difference between basal plasma glucose and plasma glucose after [Δ Glucose (%)] (i) in i.c.v. Veh- or T3-treated rats, (ii) in rats treated with Veh MD or T3 MD in the hypothalamic PVN, and (iii) hypothalamic T3 MD in selective hepatic sympathectomized (T3 MD HSx) or sham-denervated (T3 MD Sham) rats. Note the significant increase of plasma glucose in i.c.v. T3 and T3 MD-treated rats relative to their respective Veh controls. Hepatic sympathectomy did not abolish the plasma glucose increase upon T3 microdialysis. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle control group. (B) Relative difference between basal EGP and EGP after [Δ EGP (%)] (i) in i.c.v. Veh- or T3-treated rats, (ii) in rats treated with vehicle (Veh MD) or T3 MD in the hypothalamic PVN, and (iii) hypothalamic T3 MD in selective hepatic sympathectomized (T3 MD HSx) or sham-denervated (T3 MD Sham) rats. Note that the increase of EGP in response to T3 microdialysis relative to Veh-treated rats, replicated by T3 MD in sham-denervated animals, is totally prevented by selective hepatic sympathectomy. *P ≤ 0.05 Veh MD vs. T3 MD and T3 MD Sham vs. T3 MD HSx.

Plasma glucagon showed a trend toward a decrease in Veh-treated rats (Veh basal vs. after –13 ± 5%, P = 0.058), whereas it showed a nonsignificant 9 ± 6% increase in Veh T3-treated rats [ANOVA (Time*Group), P = 0.023]. However, the glucagon changes were not a determinant of EGP changes in either group (Veh MD r = –0.39, P = 0.40; T3 MD r = 0.37, P = 0.34). There were no differences in basal plasma glucagon, insulin, and corticosterone between groups. In both groups, plasma insulin and corticosterone after 2 h of MD did not differ from the basal values (Table 2).

Table 2.

Plasma hormone concentrations before (Basal) and after (2 h) vehicle and T3 MD

| Veh MD, n = 7 |

T3 MD, n = 9 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | 2 h | Basal | 2 h | |

| T3 (nmol/L) | 1.11 ± 0.05 | 1.01 ± 0.10 | 1.13 ± 0.06 | 1.14 ± 0.14 |

| T4 (nmol/L) | 74 ± 6 | 54 ± 6a | 60 ± 4 | 35 ± 4a,b |

| T3/T4 (%) | 1.60 ± 0.20 | 2.17 ± 0.49 | 1.92 ± 0.13 | 3.35 ± 0.50a |

| Insulin (pmol/L) | 291 ± 70 | 271 ± 65 | 247 ± 19 | 277 ± 28 |

| Glucagon (pg/ml) | 97 ± 7 | 85 ± 9c | 92 ± 7 | 99 ± 8 |

| Corticosterone (ng/ml) | 126 ± 71 | 120 ± 29 | 174 ± 46 | 107 ± 18 |

aP < 0.05 vs. Basal value within the same group.

bP < 0.05 vs. Veh 2 h.

cP = 0.058 vs. Bas (ANOVA factor Time*Group P = 0.023).

Plasma Thyroid Hormones.

Plasma T3 and T4 concentrations and T3/T4 ratios are depicted in Table 2. There were no differences in basal plasma T3 concentrations between Veh and T3 MD groups, and T3 concentrations did not change after MD. Of note, there was no increase in plasma T3 concentration after 2 h of T3 MD. Plasma T4 was lower in T3-treated rats as compared with vehicle after 2 h of MD. Basal plasma T4 concentrations were not significantly different between T3 MD and Veh MD rats. The plasma T3/T4 ratio increased after 2 h of T3 MD (P = 0.021), but did not alter after Veh MD.

Experiment #3: PVN T3 MD in Selective HSx and Sham-Denervated Rats.

To study the role of sympathetic projections from the hypothalamus to the liver in the observed effects on EGP, we performed T3 PVN MD in animals that had undergone either a selective surgical sympathetic denervation (T3 MD HSx, n = 8) or a sham denervation (T3 MD Sham, n = 6) of the liver. HSx animals showed a significant 85.5% reduction in noradrenaline content as compared to sham-denervated rats, with no overlap between the groups (T3 MD Sham 38.9 ± 5.9 ng/g, T3 MD HSx 5.6 ± 0.9 ng/g, P = 0.002). This decrease in noradrenaline content was similar in previous reports by our group involving selective hepatic sympathectomy (3).

Glucose, Glucose Kinetics, and Glucoregulatory Hormones.

Basal plasma glucose and basal EGP were not different between both groups, which is in line with our previous data showing no effect of sympathectomy on (basal) EGP in euthyroid rats (3). In sham-denervated rats, T3 MD induced a 19 ± 3% (P < 0.0001) increase in plasma glucose. In HSx rats, plasma glucose increased by 18 ± 3% (P = 0.002) after 2 h of T3 MD [ANOVA (Time) P < 0,0001, (Time*Group) P = 0,889] (see Fig. 3A). EGP increased by 9.9 ± 5,0% in sham-denervated rats after 2 h T3 MD, very similar to earlier results in intact hypothalamic T3-treated animals in Experiment #2 (Fig. 3B). In contrast, HSx animals showed an EGP decrease of 5.6 ± 7.2% upon hypothalamic T3 MD, similar to the EGP decrease following Veh MD in Experiment #2. The increase in the T3-treated intact (Experiment #2) or T3-treated sham-denervated (Experiment #3) animals differed significantly from the decrease seen in the vehicle-treated intact (Experiment #2) or T3-treated HSx (Experiment #3) animals, respectively (P ≤ 0.05) (see Fig. 3B).

There were no differences in basal plasma insulin and glucagon between the sham-denervated and HSx groups, and plasma insulin and glucagon did not change after 2 h of T3 MD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Plasma hormone concentrations before (Basal) and after (2 h) T3 microdialysis in sham-denervated (T3 MD Sham) and hepatic sympathectomized rats (T3 MD HSx)

| T3 MD Sham, n = 8 |

T3 MD HSx, n = 6 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | 2 h | Basal | 2 h | |

| T3 (nmol/L) | 1.17 ± 0.08 | 1.08 ± 0.10 | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 0.87 ± 0.08a |

| T4 (nmol/L) | 79 ± 5 | 50 ± 4a | 76 ± 6 | 41 ± 4a |

| T3/T4 (%) | 1.48 ± 0.07 | 2.24 ± 0.26a | 1.71 ± 0.12 | 2.26 ± 0.31 |

| Insulin (pmol/L) | 181 ± 20 | 211 ± 40 | 203 ± 31 | 189 ± 37 |

| Glucagon (pg/ml) | 60 ± 5 | 70 ± 8 | 69 ± 9 | 57 ± 9 |

aP < 0.05 vs. Basal value within the same group.

Plasma Thyroid Hormones.

Plasma T3 decreased significantly by 31 ± 3% in HSx animals after T3 MD (P < 0.0001), while T3 MD had no effect on plasma T3 in sham denervated rats (see Table 3). Plasma T4 decreased to a similar extent in both groups after T3 MD (–36.4 ± 4.7% T3 MD Sham vs. –45.9 ± 4.2% T3 MD HSx). The T3/T4 ratio was higher after T3 MD compared with basal values in sham-denervated (P = 0.012), but not in HSx animals (see Table 3).

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is that T3 administered to the hypothalamic PVN in euthyroid rats rapidly increases EGP, with a concomitant increase in plasma glucose concentration. An intact sympathetic input to the liver is essential for this hypothalamic effect of T3 on EGP to occur. Moreover, the T3-induced effects occur independently of plasma glucoregulatory hormone concentrations.

The first indication that the thyrotoxicosis-associated increase in EGP and concomitant hyperglycemia can be mimicked by central T3 administration in euthyroid rats came from our experiments involving i.c.v. T3 infusion. However, these data were not conclusive, as 5 h after central T3 infusion, plasma T3 concentrations increased above the euthyroid reference range. Thus, a causal relation between the plasma T3 increase after 5 h and the metabolic alterations after 24 h could not be excluded, despite the fact that plasma T3 had almost returned to basal values after 24 h. We decided to use bilateral MD, which enables precise local administration within the hypothalamus and thereby offers detailed neuroanatomical information, to confirm our hypothesis that T3 can modulate hepatic glucose production via actions in the hypothalamic PVN. The hypothalamic PVN not only harbors hypophysiotropic neurons projecting to the median eminence, but also contains preautonomic neurons controlling autonomic projections to the liver (12). The increase in EGP and plasma glucose upon administration of T3 in the PVN was independent of plasma T3, insulin, and corticosterone concentrations. Plasma glucagon showed a small increase in response to hypothalamic T3 relative to vehicle treatment. This effect on plasma glucagon may point to an effect of hypothalamic T3 on the endocrine pancreas. However, its small magnitude and the lack of correlation between the glucagon and EGP changes exclude that the glucagon changes are responsible to a significant extent for the observed EGP increase. Taken together, the observations are compatible with a neural (autonomic) modulation of hepatic glucose metabolism by hypothalamic T3. Indeed, we confirmed our hypothesis that hypothalamic T3 modulates EGP via sympathetic projections to the liver by demonstrating that the hypothalamic T3-induced EGP increase can be totally prevented by prior surgical selective hepatic sympathetic denervation. In addition, this denervation experiment confirmed that the T3-induced changes in glucagon release are not the main determinant of the changes in EGP.

The hypothalamic PVN contains many hypophysiotropic thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) neurons, projecting to the median eminence and regulating the hypothalamo-pituitary-thyroid axis. Hypothalamic T3 treatment may cause a down-regulation of TRH gene expression in these neurons, in turn inducing decreased thyroidal T4 and T3 secretion as a reflection of central hypothyroidism (13). Our MD experiments lasted for 2 h, which may be too rapid for modulation of TRH gene transcription, pituitary TSH release, and thyroid hormone secretion. In addition, central hypothyroidism induced by central T3 administration would be expected to cause opposite changes in glucose metabolism: that is, decreased EGP and glucose concentration (14).

It has been documented extensively that during cold stress, sympathetic stimulation of brown adipose tissue increases local T3 availability via activation of deiodinase type 2 (D2) (15). Deiodinase type 1 (D1) is the principal hepatic TH deiodinating enzyme and is a major contributor to T3 production in the rat (16). β-adrenergic blockers, such as propanolol, are widely used in the initial clinical management of hyperthyroid patients, in part because these drugs inhibit T4 to T3 conversion on the hepatic level (17). However, it is unknown if hepatic D1 activity is neurally regulated. Interestingly, in the present study i.c.v. T3 administration decreased plasma T4, whereas plasma T3 was elevated after 24 h. Given that these experiments were performed in rats treated with methimazole and thyroxine, these changes occurred independently from thyroidal TH secretion. This raises the interesting possibility of a central T3 effect on hepatic deiodinating activity. Moreover, hypothalamic T3 administration for 2 h increased the plasma T3/T4 ratio as compared with Veh treatment, which was also the case after hypothalamic T3 in sham-denervated rats, but not in rats that underwent prior selective hepatic sympathetic denervation. Collectively, these findings are compatible with the concept of sympathetic stimulation of T4 to T3 conversion by hepatic D1. By inference, we might speculate that sympathetic stimulation of hepatic T4 to T3 conversion could be partly responsible for the increase in EGP following hypothalamic T3 administration, which will be the subject of further study.

Although the observed weight loss in i.c.v. T3-treated rats in the 24 h following i.c.v. infusion may be compatible with increased energy expenditure by T3, we were surprised to find that i.c.v. T3 administration did not affect food intake in the 24 h following i.c.v. infusion as compared with Veh-treated rats. Recent studies by Kong et al. (18) involving local intrahypothalamic T3 administration provided evidence that the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus is a key nucleus for the orexigenic effects of T3. Although it is known that thyroid hormone bioavailability in the central nervous system is strongly regulated by deiodinases (in particular D2) (19), little is known about thyroid hormone-transport mechanisms between the ventricular system and specific hypothalamic nuclei (20). Consequently, the effect of i.c.v. T3 bolus infusion on local T3 tissue concentrations in the ventromedial nucleus or in other hypothalamic nuclei (and, thereby, on eating behavior) is difficult to predict at present.

The rapid time scale of the effects of intrahypothalamic T3 administration on glucose metabolism in itself fits with neural signaling from the hypothalamus to the liver via autonomic (sympathetic) efferents, whereas at first sight it may be hard to reconcile with TR-mediated effects on gene transcription and translation (21). Recently, an increasing number of rapid, so called “nongenomic” thyroid hormone effects have been reported. These may be mediated by TRs, for example via interaction of TR subtype α1 (TRα1) with the PI3K/Akt pathway (22), which is a critical downstream target of insulin signal-transduction in hypothalamic neurons regulating EGP (7, 23). Alternatively, membrane-bound receptors have emerged as high-affinity T3 binding sites that could mediate these rapid effects via nontranscriptional mechanisms (24).

In the present study, we demonstrate that the EGP increase induced by hypothalamic T3 administration is mediated via altered sympathetic outflow to the liver. Recent studies in mice have shown that suppression of TRα1 signaling via a mutation causing a 10-fold lower affinity for T3 enhances basal metabolism. This appeared to be mediated via increased sympathetic tone to brown adipose tissue, overriding the peripheral actions of the receptor (25). These observations suggested an important role for TRα1 in regulating sympathetic outflow from the hypothalamus. In contrast, the notion of increased sympathetic tone during thyrotoxicosis is not supported by experiments in β-adrenergic knockout mice focusing on cardiac physiology and metabolic rate (26). However, recent studies in patients with hyperthyroidism did show increased sympathetic tone in s.c. adipose tissue (27), increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic tone to the heart (28, 29), and increased urinary catecholamine excretion (28, 30), pointing to increased sympathetic activity during thyrotoxicosis in humans. Finally, the present findings are in line with previously reported observations from our group that the thyrotoxicosis-induced changes in (hepatic) glucose metabolism can be differentially modulated by either selective sympathetic or parasympathetic denervation of the liver (3).

Our finding that hepatic sympathectomy prevents the EGP increase, but not the plasma glucose increase induced by hypothalamic T3, points to effects on glucose metabolism other than via EGP in sympathectomized animals. Decreased peripheral glucose uptake is one of the possibilities, perhaps mediated via autonomic input to major glucose-disposing tissues, such as striated muscle and white adipose tissue (31).

We conclude that stimulation of T3-sensitive neurons in the PVN of euthyroid rats increases EGP via sympathetic projections to the liver, independently of circulating glucoregulatory hormone concentrations. Thus, we report a central pathway for modulation of hepatic glucose production by T3 involving the hypothalamic PVN and the sympathetic nervous system.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Male Wistar rats (Harlan, Horst), housed under constant conditions of temperature (21 ± 1 °C) and humidity (60 ± 2%) with a 12-h light–12-h dark schedule (lights on at 0700 h) were used for all experiments. Body weight was between 350 and 375 g. Food and drinking water were available ad libitum. All of the following experiments were conducted with the approval of the Animal Experimental Committee of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Experimental Groups.

Experiment #1.

In the first experiment rats treated with methimazole and thyroxine were equipped with unilateral cannulas aimed at the left lateral cerebral ventricle to receive an i.c.v. bolus infusion of T3 or Veh. At t = 0 and at t = 24 h, isotope dilution and blood sampling were performed for measurement of EGP, plasma glucose, and (glucoregulatory) hormone concentrations.

Experiment #2.

In the second experiment, rats were equipped with bilateral MD probes aimed at the hypothalamic PVN. After a basal EGP measurement at t = 0, isotope infusion was continued and continuous T3 or Veh MD was started. After 90 min, blood samples were obtained for measurement of EGP, plasma glucose, and (glucoregulatory) hormone concentrations.

Experiment #3.

In the third experiment, T3 MD in the PVN (see Experiment #2) was performed in surgically hepatic sympatectomized animals (T3 MD HSx, n = 8) and sham-denervated animals (T3 MD Sham, n = 6). In all PVN MD experiments, to avoid inclusion of animals that were not systemically euthyroid after 2 h of MD (see Experiment #1 in Results), we excluded rats with plasma T3 levels above the upper limit of the reference range (1.8 nmol/L) from the final analysis. To minimize bias, we excluded rats with basal insulin concentrations above the upper limit of the reference range (>655 pmol/L) from the final analysis. Reference ranges were determined as mean ± 2 SD from basal samples of 26 intact rats of the same age with no hormonal treatment. Moreover, we carefully checked MD probe placement. Only animals with bilateral probes that were positioned within or at the border of the PVN were included in the final analysis.

Hormonal Treatment.

In Experiment #1 we pretreated rats with methimazole 0.025% and 0.3% saccharin in drinking water starting 7 days before surgery, and administered T4 (1.75 μg/100 g/day) using osmotic minipumps starting at time of surgery to reinstate euthyroidism (block and replacement), as reported previously (3).

Surgery.

Animals were anesthetized using Hypnorm (Janssen; 0.05 ml/100 g body weight, i.m.) and Dormicum (Roche; 0.04 ml/100 g body weight, s.c.). In all animals an intra-atrial silicone cannula was implanted through the right jugular vein and a second silicone cannula was placed in the left carotid artery for isotope infusion and blood sampling. Both cannulas were tunnelled to the head s.c (3). Stainless-steel i.c.v. probes were implanted in the left cerebral ventricle using the following stereotaxic coordinates: anteroposterior, –0.8 mm; lateral, +2.0 mm; ventral, –3.2 mm, with the toothbar set at –3.4 mm. The U-shaped tip of the MD probe was 1.5 mm long, 0.7 mm wide, and 0.2 mm thick (9). Bilateral MD probes were stereotaxically implanted, directly lateral to the PVN, using the following stereotaxic coordinates: anteroposterior, –1.8 mm; lateral, 2.0 mm; ventral, –8.1 mm, with the toothbar set at –3.4 mm. HSx was performed as described previously (3, 9). HSx involves an impairment of both efferent and afferent nerves, but this procedure does not impair the parasympathetic vagal input to the liver (9). Sham-operated rats underwent the same surgical procedures as HSx animals, except for transection of the neural tissue. To confirm successful sympathetic denervation, HPLC for noradrenaline was performed on liver homogenates, as described earlier (3).

Stable Isotope Dilution and Central T3 Administration.

General Procedure.

Ten days after surgery, stable isotope dilution was performed combined with central administration of T3. In the afternoon on the day before the central T3 experiments, rats were connected to a metal collar attached to polyethylene tubing (for blood sampling and infusion), which was kept out of reach of the animals by a counter-balanced beam. This allowed all subsequent manipulations to be performed outside the cages without handling the animals. At 1400 h, a blood sample was obtained for determination of basal plasma thyroid hormones concentrations. On the day of the central T3 experiments, (basal) EGP was determined using the stable isotope tracer [6,6-2H2]-glucose, as described previously (3).

Experiment #1: Bolus T3 Infusion.

After the last basal blood sample, the isotope infusion pump was stopped. Animals received an i.c.v. bolus infusion of either 1.5 nmol/100 g body weight T3 (Sigma) in 0.05 M NaOH (T3 i.c.v. group) or 0.05 M NaOH (Veh group) in 4 μl over 160 sec. This dose and the 24-h time interval were adopted from Goldman et al., showing positive chronotropic effects of i.c.v. T3 in hypothyroid rats (32). After the bolus infusion, food was placed back in the cages. Five hours after the i.c.v. bolus infusion, a blood sample was obtained for measurement of plasma T3. The next day, the infusion of [6,6-2H2]-glucose was started again, with subsequent blood sampling for measurement of glucose concentration, hormones, and isotopic enrichment. All experimental manipulations on the second day were performed in the same way and at the same time-points as on the day before.

Experiments #2 and #3: T3 MD in the Hypothalamic PVN.

Recovery of the MD probes for T3 was 0.24%, as established by in vitro experiments. A solution of 155 μg/ml T3 dissolved in 2 mM NaOH in PBS (pH 9), was infused through the MD probe-inlet equivalent to 100 pmol/h T3 (T3 MD group). Veh MD rats were microdialysed with 2 mM NaOH in PBS (pH 9). The dose of 100 pmol/h T3 was chosen based on the study by Kong et al. (18), which is, to our knowledge, the only study to date reporting local brain infusion of T3. Ringer dialysis (3 μl/min) was performed from 60 min before the start of isotope infusion and continued until after the last basal blood sample (t = 0 min), when the Ringer was replaced by either T3 or vehicle. Ninety minutes after the start of the T3 vehicle administration (with continued isotope infusion), blood samples (200 μl) were obtained for measurement of glucose concentration, glucoregulatory hormones (t = 90 min), T3 and T4 (t = 120 min), and isotopic enrichment (t = 90, 100, 110, and 120 min).

After the central infusion experiments, rats were killed and whole brains were frozen for subsequent analysis of MD probe placement. Hypothalamic (PVN) placement of bilateral probes was evaluated blindly in each experimental animal by an experienced neuro-anatomist and scored on the basis of anteroposteriority, laterality, and dorsoventrality. EGP was calculated from isotope enrichment using adapted Steele equations (33).

Plasma Analyses.

Plasma glucose concentrations were determined in blood spots using a glucose meter (Freestyle, Abbott) with inter- and intra-assay CVs of less than 6% and 4%, respectively. Plasma concentrations of the thyroid hormones T3 and T4 were determined by in-house RIA (34). Plasma TSH concentrations were determined by a chemiluminescent immunoassay, using a rat-specific standard and plasma insulin; glucagon and corticosterone concentrations were measured using commercially available kits (see SI Materials and Methods); [6,6-2H2]-glucose enrichment was measured as described earlier (35).

Statistics.

Data were analyzed by ANOVA with repeated measures, with treatment group (T3 or Veh) as the between-animal factor and time (basal or after) as the within-animal factor. Paired-sample and 2-sample Student's t-test were used as post hoc tests to determine where time-points within treatment groups and between treatment groups differed from each other, respectively. Post hoc tests were performed if ANOVA revealed significance. Mann Whitney U-tests were used for analysis of Δ in time (before–after intervention) between groups. Spearman correlation was used to test for associations between factors. Significance was defined at P ≤ 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank E.M. Johannesma-Brian and A.F.C. Ruiter for performing the hormone and isotope analyses. Support for this study was provided in part by the Ludgardine Bouwman-Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0805355106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Franklyn JA. Metabolic changes in thyrotoxicosis. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, editors. The Thyroid: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 8th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 667–672. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimitriadis GD, Raptis SA. Thyroid hormone excess and glucose intolerance. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2001;109(Suppl 2):S225–S239. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klieverik LP, et al. Effects of Thyrotoxicosis and selective hepatic autonomic denervation on hepatic glucose metabolism in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;294:E513–E520. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00659.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prodi E, Obici S. Minireview: the brain as a molecular target for diabetic therapy. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2664–2669. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clegg DJ, Brown LM, Woods SC, Benoit SC. Gonadal hormones determine sensitivity to central leptin and insulin. Diabetes. 2006;55:978–987. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cusin I, Rouru J, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F. Intracerebroventricular glucocorticoid infusion in normal rats: induction of parasympathetic-mediated obesity and insulin resistance. Obes Res. 2001;9:401–406. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obici S, Zhang BB, Karkanias G, Rossetti L. Hypothalamic insulin signaling is required for inhibition of glucose production. Nat Med. 2002;8:1376–1382. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obici S, Feng Z, Karkanias G, Baskin DG, Rossetti L. Decreasing hypothalamic insulin receptors causes hyperphagia and insulin resistance in rats. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:566–572. doi: 10.1038/nn0602-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalsbeek A, La Fleur S, Van Heijningen C, Buijs RM. Suprachiasmatic GABAergic inputs to the paraventricular nucleus control plasma glucose concentrations in the rat via sympathetic innervation of the liver. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7604–7613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5328-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alkemade A, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor expression in the human hypothalamus and anterior pituitary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:904–912. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lechan RM, Qi Y, Jackson IM, Mahdavi V. Identification of thyroid hormone receptor isoforms in thyrotropin-releasing hormone neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Endocrinology. 1994;135(1):92–100. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.1.7516871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Fleur SE, Kalsbeek A, Wortel J, Buijs RM. Polysynaptic neural pathways between the hypothalamus, including the suprachiasmatic nucleus, and the liver. Brain Res. 2000;871(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segerson TP, et al. Thyroid hormone regulates TRH biosynthesis in the paraventricular nucleus of the rat hypothalamus. Science. 1987;238(4823):78–80. doi: 10.1126/science.3116669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okajima F, Ui M. Metabolism of glucose in hyper- and hypo-thyroid rats in vivo. Biochem J. 1979;182:565–575. doi: 10.1042/bj1820565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva JE. Thermogenic mechanisms and their hormonal regulation. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:435–464. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen TT, Chapa F, DiStefano JJ. Direct measurement of the contributions of type I and type II 5′-deiodinases to whole body steady state 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine production from thyroxine in the rat. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4626–4633. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.11.6323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiersinga WM. Propranolol and thyroid hormone metabolism. Thyroid. 1991;1:273–277. doi: 10.1089/thy.1991.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong WM, et al. Triiodothyronine stimulates food intake via the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus independent of changes in energy expenditure. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5252–5258. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernal J. Action of thyroid hormone in brain. J Endocrinol Invest. 2002;25:268–288. doi: 10.1007/BF03344003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alkemade A, et al. Neuroanatomical pathways for thyroid hormone feedback in the human hypothalamus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4322–4334. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen PM. Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1097–1142. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiroi Y, et al. Rapid nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14104–14109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601600103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niswender KD, et al. Insulin activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key mediator of insulin-induced anorexia. Diabetes. 2003;52:227–231. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis PJ, Leonard JL, Davis FB. Mechanisms of nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sjogren M, et al. Hypermetabolism in mice caused by the central action of an unliganded thyroid hormone receptor alpha1. EMBO J. 2007;145:2767–2774. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bachman ES, et al. The metabolic and cardiovascular effects of hyperthyroidism are largely independent of beta-adrenergic stimulation. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2767–2774. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haluzik M, et al. Effects of hypo- and hyperthyroidism on noradrenergic activity and glycerol concentrations in human subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue assessed with microdialysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5605–5608. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burggraaf J, et al. Sympathovagal imbalance in hyperthyroidism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281(1):E190–E195. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.1.E190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cacciatori V, et al. Power spectral analysis of heart rate in hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2828–2835. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.8.8768838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eustatia-Rutten CF, et al. Autonomic nervous system function in chronic exogenous subclinical thyrotoxicosis and the effect of restoring euthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2835–2841. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreier F, et al. Tracing from fat tissue, liver and pancreas: A neuroanatomical framework for the role of the brain in type 2 diabetes. Endocrinology. 2005;147:1140–1147. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldman M, et al. Intrathecal triiodothyronine administration causes greater heart rate stimulation in hypothyroid rats than intravenously delivered hormone. Evidence for a central nervous system site of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1622–1625. doi: 10.1172/JCI112146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steele R. Influences of glucose loading and of injected insulin on hepatic glucose output. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1959;82:420–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1959.tb44923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalsbeek A, et al. Functional connections between the suprachiasmatic nucleus and the thyroid gland as revealed by lesioning and viral tracing techniques in the rat. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3832–3841. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.10.7709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ackermans MT, et al. The quantification of gluconeogenesis in healthy men by (2)H2O and [2-(13)C]glycerol yields different results. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2220–2226. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.