Abstract

Purpose

Open partial nephrectomy (OPN) is now the preferred treatment for most T1a and selected T1b tumours. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN), created to reduce the morbidity associated with OPN, is now a viable option when performed by experienced laparoscopic surgeons. We retrospectively review our LPN experience and propose a new parameter, the LPN utilization rate (LPN-UR), defined as the probability of any referred patient with a T1 tumour undergoing LPN before the surgeon’s knowledge of its imaging characteristics, to define the role of LPN at our institution.

Methods

Between March 2003 and August 2008, 47 consecutive patients underwent LPN for T1 tumours. All patients underwent transient en bloc vascular occlusion of the renal hilum for cold-scissor tumour excisions. Preoperative, intraoperative, postoperative and pathological data were collected. The LPN-URs for 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008 were calculated.

Results

There were 31 nonhilar tumours and 16 hilar tumours. All procedures were completed laparoscopically. Mean tumour size was 3.8 (range 1.5–7.2) cm. Mean operating time was 2.8 (range 1.2–4.5) hours. Mean hospital stay was 5.2 (range 2.0–15.0) days. Mean warm ischemic time (WIT) was 32.7 (range 14.2–50.4) minutes. Six patients (12.8%) received blood transfusions and 1 patient required an emergency nephrectomy for bleeding. One patient developed urinary leakage. One patient developed a late calyceal stricture. Mean postoperative differential renal function was 35%:50%. Median follow-up was 18 months. Pathological examination of all tumours revealed 38/47 (80.9%) malignant tumours with 2 positive surgical margins (4.3%). The LPN-URs for 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008 were 50%, 54%, 63% and 93%, respectively, for all T1 tumours.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy can be safely performed and used for treatment of most T1 tumours referred to our institution. Long-term follow-up will be required to determine the oncological efficacy of LPN. Every effort should be made to further reduce the WIT. The LPN-UR is a useful parameter for consulting referring physicians and patients.

Résumé

Objectif

La néphrectomie partielle ouverte (NPO) constitue actuellement le traitement de choix pour la plupart des cas de tumeurs T1a et de certaines tumeurs T1b. La néphrectomie partielle laparoscopique (NPL), technique développée pour réduire la morbidité associée à la NPO, représente maintenant une option intéressante pour les chirurgiens expérimentés en laparoscopie. Nous avons fait une analyse rétrospective de notre expérience avec la NPL et nous proposons un nouveau paramètre — le taux d’utilisation de la NPL (TU-NPL) — afin de mieux définir le rôle de cette technique dans notre établissement.

Méthodologie

Entre mars 2003 et août 2008, 47 patients consécutifs ont subi une NPL pour traiter une tumeur T1. Tous les patients ont subi un clampage temporaire en bloc des vaisseaux rénaux au niveau du hile en vue d’une excision tumorale à froid par ciseaux. Des données opératoires et pathologiques ont été recueillies avant, pendant et après l’intervention. Les TU-NPL pour 2005, 2006, 2007 et 2008 ont été calculés.

Résultats

On a relevé 31 tumeurs non hilaires et 16 tumeurs hilaires. Toutes les interventions ont été effectuées par laparoscopie. La taille moyenne des tumeurs était de 3,8 (écart : 1,5 à 7,2) cm. Le temps moyen passé en salle d’opération était de 2,8 (écart : 1,2 à 4,5) heures. La durée moyenne de l’hospitalisation était de 5,2 (écart : 2,0 à 15,0) jours. La durée moyenne de l’ischémie chaude était de 32,7 (écart : 14,2 à 50,4) min. Six patients (12,8 %) ont reçu des transfusions sanguines et un patient a dû subir une néphrectomie d’urgence en raison d’une hémorragie. Un patient a présenté une incontinence urinaire et un autre, une sténose tardive au niveau des calices. La fonction rénale différentielle moyenne après l’opération était de 35 % : 50 %. La durée médiane du suivi était de 18 mois. L’analyse pathologique a révélé que 38 tumeurs sur 47 (80,9 %) étaient malignes; 2 tumeurs (4,3 %) présentaient des marges chirurgicales positives. Les TU-NPL pour 2005, 2006, 2007 et 2008 étaient respectivement de 50 %, 54 %, 63% et 93 % pour les tumeurs T1.

Conclusion

La NPL peut être effectuée sans danger et utilisée pour le traitement de la plupart des cas de tumeurs T1 traités par notre établissement. Un suivi à long terme est nécessaire pour déterminer l’efficacité oncologique de la NPL. Tous les efforts doivent être déployés pour réduire davantage la durée de l’ischémie chaude. Le TU-NPL est un paramètre de consultation utile pour les médecins et les patients.

Introduction

In the last decade, more and more evidence has supported the notion that open partial nephrectomy (OPN) is now the optimal treatment modality for most T1a1,2 and an option for selected T1b3,4 renal cortical tumours. Concurrent with this development, laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) was created to reduce the morbidity while maintaining the oncological efficacy of OPN, and to preserve long-term renal function, and is now a viable option when performed by experienced laparoscopic surgeons.5 However, the population-based data in the United States in 2002 suggested that only 20% of the renal cortical tumours between 2 and 4 cm in diameter were treated by partial nephrectomy.6 Similarly, in England, only 4% of 2671 renal cortical tumours were treated by partial nephrectomy in 2002.7 These data indicate that the procedure is underused despite its benefits. Recognizing this similar shortcoming at our institution, we have become actively involved in our LPN program for treatment of T1 tumours. This paper summarizes the LPN experience at our institution, which was initiated in 2003, active in 2005 and has now been a routine procedure since 2008. We also propose a new parameter in this summary, namely the LPN utilization rate (LPN-UR), defined as the probability of a referred patient with a T1 tumour undergoing LPN before the surgeon’s knowledge of the tumour’s imaging characteristics. We believe this parameter will be useful in clinical practice.

LPN utilization rate

For T1N0M0 renal cortical tumours, excluding active surveillance and ablative technologies, there are presently 4 treatment options: LPN, OPN, laparoscopic radical nephrectomy (LRN) and open radical nephrectomy (ORN). By using as the denominator the total number of all T1 tumours originally referred to the institution, one can calculate and inform both the patient and referring physician of the probability that the patient will be treated with the open or minimally invasive nephron-sparing surgical techniques.

Calculations

Probability that a partial nephrectomy will be performed:

Probability that an OPN will be performed:

Probability that an LPN will be performed:

In our institution, all T1N0M0 renal cortical tumours are treated with either LPN or LRN. There was no OPN or ORN performed, and therefore,

Methods

After approval from the local ethics research board, we retrospectively reviewed 47 consecutive patients’ charts who underwent LPN between March 2003 and August 2008, as performed by one surgeon (E.T.). During this same period, all T1N0M0 renal cortical tumours were treated by LPN or LRN. There were no OPN or ORN procedures performed, as we attempted LPN for all candidates who we felt were suitable for partial nephrectomy at our level of confidence. All patients underwent preoperative 3-dimensional computed tomography (CT) at our institution. The maximum tumour diameter was 7.2 cm.

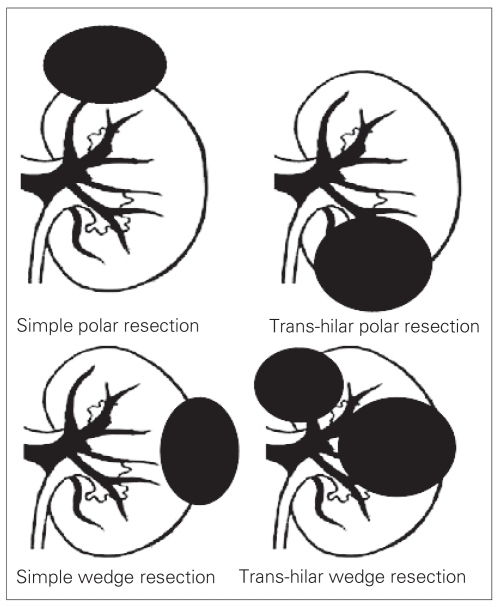

Tumours were classified into 4 groups according to their location and depth of parenchymal involvement. Tumour locations are either upper or lower pole (polar resection), or midpole (wedge resection). Parenchymal involvement is described as either hilar or nonhilar. A tumour is classified as hilar when the plane of excision is in close proximity (about 5.0 mm) to major renal vessels. Otherwise, it is classified as nonhilar. The 4 categories of LPN are depicted in Figure 1. Examples of these categories from this patient cohort are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Fig. 1.

The 4 categories of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy.

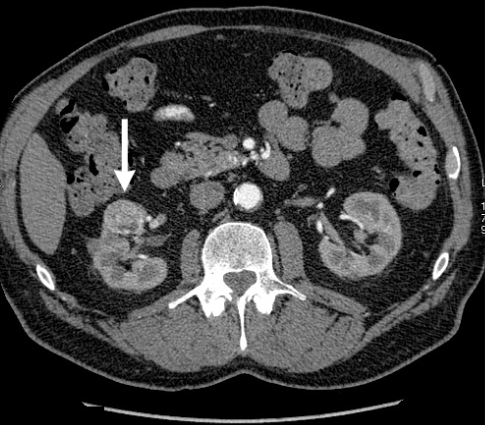

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography scan showing midpole tumour, indicating simple wedge resection.

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography scan showing midpole tumour, indicating trans-hilar wedge resection.

Fig. 4.

Computed tomography scan showing lower-pole tumour, indicating trans-hilar polar resection.

Surgical techniques

We routinely employed a 5-port transperitoneal approach. The procedure is briefly described as follows: after the colon and, if needed, the duodenum were mobilized off the Gerota fascia, we identified the ureter, dissected it up to the renal hilum and retracted it out of harm’s way. We then mobilized the renal artery and vein in an en bloc fashion to prepare it for temporary occlusion with a Satinsky clamp (Teleflex). We dissected the renal capsule off its perinephric fat completely, except for the tumour-bearing part, to orient the kidney for the cold-scissor excision of the tumour and the repair of the renal defects. For hilar tumours, we extensively dissected the arterial and venous branches in the renal hilum to create a safe plane for tumour excision. We then applied a Satinsky clamp to occlude the main renal artery and vein en bloc. The tumour was then excised with cold scissors in a bloodless field. We then closed the renal defect in 2 layers: the first layer for closure of the collecting system and hemostasis, and the second layer for reapproximation of the cut parenchymal edge. We then applied a hemostatic agent (Floseal, Baxter) on the suture line to further secure hemostasis. No surgical bolsters were used. The Satinsky clamp was then removed. The procedure was then completed by leaving a drain in the proximity of the partial nephrectomy bed.

Data collection

We collected preoperative data including patient demographics, tumour size and location, depth of parenchymal involvement, intraoperative data including surgical time and warm ischemic time (WIT), and postoperative data including need for blood transfusion, urinary leakage requiring intervention, hospital stay and renal function as per MAG3 renal scan. Tumour pathology and positive surgical margins were recorded. We calculated the LPN-UR for 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008. Since we only performed LPN sporadically for the most favourable and mainly exophytic tumours in 2003 and 2004, these were excluded from the LPN-UR calculations.

Results

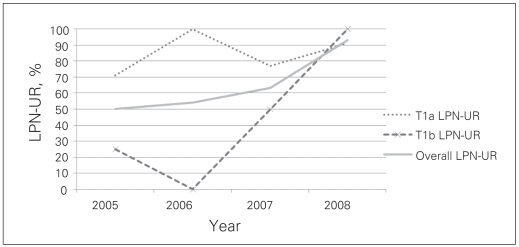

All 47 patients had their partial nephrectomy completed laparoscopically — there were no open conversions. Patient demographics, tumour size and location, mean surgical time, WIT, tumour pathology, hospital stay, overall LPN-UR, T1a LPN-UR and T1b LPN-UR were all recorded and are presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. Figure 5 is a graphic representation of our learning curve with LPN as reflected by our LPN-URs. The mean tumour size of 3.8 cm in our study is considerably larger than the mean tumour size in other series. Our mean WIT of 32.7 minutes is also higher than that of other series. Postoperative furosemide renography was available in 22 patients with a mean differential renal function of 35%:50% on the operated kidney. Six patients received intraoperative and postoperative transfusions.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and general data

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Total no. of patients | 47 |

| Mean age | 65.6 yr |

| Male:female | 31 (67%):15 (33%) |

| Mean tumour size | 3.8 (range 1.5–7.2) cm |

| Mean surgical time | 2.8 (range 1.2–4.5) h |

| Hgb change, pre- and postoperatively | 2.5 (0.3–6.0) g/L |

| Mean warm ischemic time | 32.7 (range 14.2–50.4) min |

| Mean hospital stay | 5.2 (range 2.0–15.0) d |

| Tumour pathology | 81% malignant |

| Mean postoperative differential renal function as determined by MAG3 renal scan (available for 22 patients) | 35%:50% (range 19%–50%) |

| LPN-UR | 67% (2005–2008) |

Hgb = hemoglobin; LPN-UR = laparoscopic partial nephrectomy utilization rate.

Table 2.

Preoperative tumour characteristics as found on computed tomography

| No. (%) of patients,*n = 47

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour location | Nonhilar | Hilar | Total |

| Polar | 27 (57) | 7 (15) | 34 (72) |

| Central | 6 (13) | 7 (15) | 13 (28) |

| Total | 33 (70) | 14 (30) | 47 (100) |

| Mean tumour size, cm | Nonhilar | Hilar | Total |

| Polar | 3.5 | 6.1 | 4.0 |

| Central | 2.7 | 3.4 | 3.1 |

| Total | 3.4 | 4.8 | 3.8 |

Unless otherwise indicated.

Table 3.

Surgical complications (including positive/ negative surgical margin)

| Type of complication | No. of complications | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Positive surgical margin | 2 | 1: LRN in 3 weeks

1: active surveillance |

| Hemorrhage | 7 | 6: blood transfusion

1: laparotomy and total nephrectomy |

| Urinary fistula | 1 | Resolved with double J stenting |

| Delayed calyceal infundibular stricture | 1 | Conservative |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | Anticoagulation |

| Total | 12/47 (26%) |

LRN = laparoscopic partial nephrectomy.

Table 4.

Tumour pathology

| Tumour type | No. (%) of patients, n = 47* |

|---|---|

| Benign | 9 (19) |

| Chocolate cyst | 1 |

| Angiomyolipoma | 2 |

| Oncocytoma | 4 |

| Cortical adenoma | 1 |

| Metanephric nephroma | 1 |

| Malignant | 38 (81) |

| Clear cell | 34 |

| Papillary | 3 |

| Chromophobe | 1 |

| Fuhrman grade, n = 33 | |

| I–II | 25 (76) |

| III–IV | 8 (24) |

Unless otherwise indicated.

Table 5.

Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy utilization rate

| No. of patients

|

LPN-UR by tumour type (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | LPN | RN (< 7 cm) | LPN-UR (%) | T1a | T1b |

| 2005 | 5 | 5 | 5/10 (50) | 4/7 (71) | 1/4 (25) |

| 2006 | 7 | 9 | 7/13 (54) | 12/12 (100) | 0/1 (0) |

| 2007 | 17 | 10 | 17/27 (63) | 10/13 (77) | 7/14 (50) |

| 2008 | 14 | 1 | 14/15 (93) | 10/11 (91) | 4/4 (100) |

| Total | 43 | 25 | 43/65 (66) | 36/43 (84) | 12/23 (52) |

LPN = laparoscopic partial nephrectomy; LPN-UR = laparoscopic partial nephrectomy utilization rate; RN = radical nephrectomy.

Fig. 5.

Graphic representation of the learning curve with laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) as reflected by the LPN utilization rate (LPN-UR) (2005–2008).

Two of the patients in our study had combined procedures. One patient had an LPN performed in conjunction with a laparoscopic radical prostatectomy, and his total operating time was 8.5 hours. The second patient had an LPN performed initially, which was followed by an open sigmoid resection; his operating time was 5 hours. Both patients recovered uneventfully.

Two patients in our cohort presented with a solitary kidney. The first patient, a 69-year-old woman, presented with a 6.1-cm right lower pole renal tumour. She underwent a trans-hilar wedge resection with a WIT of 44 minutes, and her serum creatinine level increased from 128 μmol/L at admission to hospital to 329 μmol/L at the time of discharge (10 d). The second patient presented with a 5.2-cm right upper pole renal mass and underwent a nonhilar, simple polar resection. His serum creatinine level rose from 137 μmol/L at admission to hospital to 159 μmol/L at the time of discharge (12 d). Neither of the 2 patients required temporary dialysis.

There were 2 unique complications in our study: one patient with a 3.0-cm left upper pole tumour had a small laceration in the main renal vein during hilar dissection. This was repaired with 3–0 vascular sutures and the rest of the procedure was performed without any further bleeding from the laceration. However, hemodynamic instability occurred in the recovery room, requiring fluid and blood resuscitation, and an emergency laparotomy. During the laparotomy, it was noted that the laceration had reopened, and a radical nephrectomy was performed. The second complication occurred in a patient with a 6.0-cm right lower pole tumour who underwent a trans-hilar right polar nephrectomy with an uneventful postoperative course. The patient was discharged 4 days later only to present in 3 weeks’ time with right flank pain. Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed urinary extravasation in the partial nephrectomy bed. Cystoscopy and retrograde pyelography confirmed the urinary extravasation from an infundibular stricture, which was dilated and stented for 6 weeks. These 2 cases underscore the importance of using meticulous reconstructive techniques.

Discussion

In recent years, there has been a dramatic rise in the detection of small renal tumours owing to the widespread use of cross-section imaging. Open partial nephrectomy, now the standard of care for small renal tumours, is gradually being challenged by LPN for the hope of further decreasing morbidity. Gill and colleagues8 were the first to demonstrate that LPN can be done by reproducing the principles of OPN. In a large series of 1800 consecutive patients treated with either OPN or LPN at Cleveland Clinic, Mayo Clinic and Johns Hopkins University, Gill and coauthors9 found that patients who underwent LPN had shorter operating times, decreased operative blood loss and decreased hospital stays, but had longer WIT and a higher incidence of postoperative urological complications. Since this series is the largest of its kind, we argue that its results can be used as a landmark when interpreting our own data.

Our technical classification of T1 tumours for LPN is notably different from those previously proposed. We argue that the classification by Weld and colleagues10 of exophytic and endophytic tumours, which is based on the percentage of parenchymal involvement of the tumour, does not truly reflect the actual depth of parenchymal involvement and its proximity to the renal hilum. Another proposed classification11 includes 3 categories: peripheral, central and hilar tumours. In this classification, hilar tumours are defined as those which abut on major renal arteries and veins. We feel that this definition is too stringent and argue that tumours whose plane of excision is within about 5.0 mm of major renal vessels will require similar dissections for safe surgery.

Laparoscopic intraoperative ultrasonography has been suggested to assist the surgeon in localizing and excising tumours during LPN.5 Since we have never had a “totally submerged renal tumor,” and since we were satisfied with our surgical visibility during cold-scissor tumour excision with a positive surgical margin rate of 4%, we do not believe intraoperative ultrasonography would play a significant role in improving our surgical outcome at this time. We rely on preoperative 3-dimensional CT to detect tumours’ multicentricity in our patient cohort.

Two of our patients had combined procedures. Although this raises concern about a prolonged operating time and an increased likelihood of surgical complications, both patients wished to have the combined procedure performed at the earliest possible time to alleviate their anxiety about having 2 simultaneous malignancies. Presently, we only proceed with the second procedure if the first was completed uneventfully.

The Canadian Kidney Cancer Forum 200812 has recommended OPN in general and LPN in centres with laparoscopic expertise for treatment of small renal masses. The consensus also indicated that LRN is an option when expertise for partial nephrectomy is not available. We feel that the term “expertise” is somewhat arbitrary, and therefore argue that radical nephrectomy, open or laparoscopic, may result in the unnecessary removal of healthy nephrons in the treatment of most T1a tumours.13–16 As for T1b tumours, LRN is the suggested treatment of choice, with LPN as an option when technically feasible. For any T1 tumour that is beyond our level of expertise, our present policy is to obtain a second opinion from another institution before we proceed with LRN. This will maximize the patient’s opportunity to preserve his or her renal function. Before 2005, we only performed LPN sporadically with the most favourable nonhilar tumours (exophytic, small polar tumours). In 2005 and 2006, we began to consider LPN for all referred patients with T1 tumours, but, based on our level of expertise, we were only able to recommend LPN to 84% of all referred patients with T1a tumours (T1a LPN-UR: 84%), and none to patients with T1b tumours (T1b LPN-UR: 0%). In 2008, our improved level of expertise allowed us to recommend LPN to 93% of patients with T1a and 100% of patients with T1b tumours. The only patient with a T1a tumour treated with LRN in 2008 was a 53-year-old woman who was taking warfarin because of her history of a mechanical heart valve replacement. Although LPN was offered as an option, she chose LRN. As depicted in Figure 5, the continued improvement of LPN-UR for all T1 tumours from 2005 to 2008 (from 50% to 93%) suggests that, with experience, most T1 tumours can be treated with LPN.

The LPN-UR is a new parameter which we feel will serve 2 purposes: first, it will reflect the current state of our learning curve with LPN and, second, it will be a useful reference for both the referring physician and the patient. The LPN-UR will allow all 3 parties — urologist, referring doctor and patient — to have a quantitative expectation of the probability that a patient with a T1 tumour will undergo LPN at our institution, thus assisting the patient in making an informed decision about his or her treatment.

Presently, we believe that the standard of care for small renal masses (< 4 cm) suspicious for renal malignancy is nephron-sparing surgery. Renal mass biopsy is indicated in selected patients to exclude metastatic disease, lymphoma and renal abscess, thus obviating the need for surgery. We also recognize that this belief can be short-lived. As we are more aware of the limited biological potential and slow growth rate of small renal masses (20%–30% benign lesions, 87.5% low-grade tumours, average growth rate 0.25 cm per year),17 an expanding role of renal mass biopsies may even allow more selected patients to avoid the need for nephron-sparing surgery.

Although there was no tumour recurrence in our patient cohort, the follow-up was too short (median 18 mo) to assess the oncological efficacy of LPN at our institution. Lane and Gill18 reported oncological outcomes in 56 patients with a minimum follow-up of 5 years or more. In this study, the 5-year cancer-specific survival rate was 100%, thus confirming the long-term oncological efficacy of LPNs. There were 2 positive surgical margins in our study: the first occurred early in our series and was treated with a completion-LRN 3 weeks after the LPN owing to patient anxiety, and the second patient was followed by active surveillance, which is our present strategy. The authors of one recent study19 of 1400 patients with a positive surgical margin rate of 5.5% noted that the impact of a positive surgical margin did not adversely affect the local recurrence rate or the metastatic progression rate (median follow-up 3.9 yr).

Our transfusion rate of 15% is high when compared with reports in the literature.9,11 We attribute this to 3 potential factors: the surgeon’s experience and initial learning curve, larger tumours (mean tumour size 3.8 cm, 23% of which were T1b tumours), and a higher percentage of hilar tumours (30%). We recognize our definition of hilar tumours is less strict than that of others.11,20 Reports of transfusion rate for hilar tumours have been in the range of 12% to 22%. Nonetheless, with experience, our transfusion rate has improved (1 unit in the last 10 cases). This fact also attests to the significance of the learning curve.

We did not investigate our patient cohort for urinary leakage until postoperative day 3, only if the patient continued to have a high output from the Jackson–Pratt drain. Using this criteria, we only had 1 case of urinary leakage that was resolved with double J stenting.

The mean length of stay of 5 days found in our study is also longer than reported (3–4 days).9 This is likely because of our less stringent criteria for hospital discharge, as a substantial portion of our patient cohort are from rural Saskatchewan and are without immediate medical access. We believe the implementation of a clinical care pathway and an “overnight stay” in the proximity of our centre will improve our current outcome.

Of particular note is our mean WIT for the entire series of 32.7 minutes, an elevated value when compared with Gill and colleagues’9 multicentre series mean WIT of 30.7 minutes. However, in our series, 25% of our patients had T1b tumours compared with the 8.8% in Gill and colleagues’ series. Since, in our experience, the WIT for T1b tumours is longer than that of T1a tumours (means of 35.1 v. 31.8 min, respectively), this discrepancy in mean WIT between our study and that of Gill and colleagues can be explained by our larger ratio of T1b to T1a tumours. Future efforts should nonetheless be made to further decrease the WIT to 30 minutes or less to preserve maximum renal function.

We rely on MAG3 renal scans for assessment of renal function after LPN. We recognize that the scan fails to distinguish renal damage secondary to warm ischemia, from loss of healthy renal parenchyma associated with tumour excision. An improved parameter is needed in the future. As long as the patient has a normal contralateral renal unit, it is our opinion that measurements of serum creatinine, pre- and postoperatively, have limited value. On the other hand, 24-hour creatinine clearance measured pre- and postoperatively may supplement MAG3 renal scans as a measurement of total renal function.

Limitations

There were several limitations in our study. Of primary concern is the retrospective nature of our study, and its small sample size owing to our institution’s short history with LPN. Therefore, our results will require confirmation from other centres performing similar studies. Furthermore, our short median follow-up (18 mo) precludes us from drawing conclusions regarding the oncological efficacy of LPN at our institution. Longer follow-up will be required. Finally, since the entire patient cohort was treated by one surgeon, the results contain inherent bias and thus may not be applicable to the general urological community.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy is a technically demanding procedure that involves a considerable learning curve. With experience, however, most of the T1a and T1b tumours can be approached laparoscopically without compromising the surgical margins. Blood loss requiring transfusion remains the most common complication of this procedure, and every effort should be made to reduce the WIT. Longer follow-up in this patient cohort will be required to assess its oncological efficacy. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy is now the preferred approach for treatment of most T1 tumours at our institution. We believe the LPN-UR is a useful reference at our institution when consulting the referring physicians and patients. Because of the complexity of the operation, LPN should only be an option in centres with extensive laparoscopic experience.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

See related article on page 119

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Fergany AF, Hafez K, Novick A. Long-term results of nephron sparing surgery for localized renal cell carcinoma: 10-year followup. J Urol. 2000;163:442–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herr HW. Partial nephrectomy for unilateral renal carcinoma and a normal contralateral kidney: 10-year followup. J Urol. 1999;161:33–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)62052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patard JJ, Shvarts O, Lam J, et al. Safety and efficacy of partial nephrectomy for all t1 tumors based on an international multicenter experience. J Urol. 2004;171:2181–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000124846.37299.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker F, Siemer S, Hack M, et al. Excellent long-term cancer control with elective nephron-sparing surgery for selected renal cell carcinomas measuring more than 4 cm. Eur Urol. 2006;49:1058–63. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aron M, Haber G-P, Gill I. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. BJU Int. 2007;99:1258–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller DC, Hollingsworth J, Hafez K, et al. Partial nephrectomy for small renal masses: an emerging quality of care concern. J Urol. 2006;175:853–7. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuttall M, Cathcart P, Van der Meulen J, et al. A description of radical nephrectomy practice and outcomes in england. BJU Int. 2005;96:58–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill IS, Desai M, Kaouk J, et al. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for renal tumor: duplicating open surgical techniques. J Urol. 2002;167:469–74. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)69066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill IS, Kavoussi L, Lane B, et al. Comparison of 1,800 laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomies for single renal tumors. J Urol. 2007;178:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weld KJ, Venkatesh R, Huang J, et al. Evolution of surgical technique and patient outcomes for laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. Urology. 2006;67:502–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richstone L, Montag S, Ost M, et al. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for hilar tumors: evaluation of short-term oncologic outcome. Urology. 2008;71:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Management of kidney cancer: Canadian Kidney Cancer Forum Consensus Statement. Can Urol Assoc J. 2008;2:175–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russo P. Open partial nephrectomy: an essential operation with an expanding role. Curr Opin Urol. 2007;17:309–15. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e328277f1a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau WK, Blute ML, Weaver AL, et al. Matched comparison of radical nephrectomy vs nephron-sparing surgery in patients with unilateral renal cell carcinoma and a normal contralateral kidney. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1236–42. doi: 10.4065/75.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKiernan J, Simmons R, Katz J, et al. Natural history of chronic renal insufficiency after partial and radical nephrectomy. Urology. 2002;59:816–20. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01501-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM, et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumors: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:735–40. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70803-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane BR, Samplaski M, Herts B, et al. Renal mass biopsy—a renaissance? J Urol. 2008;179:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lane BR, Gill I. 5-year outcomes of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. J Urol. 2007;177:70–4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yossepowitch O, Thompson R, Leibovich B, et al. Positive surgical margins at partial nephrectomy: predictors and oncological outcomes. J Urol. 2008;179:2158–63. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill IS, Columbo JR, Jr, Frank I, et al. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for hilar tumors. J Urol. 2005;174:850–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000169493.05498.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]