Abstract

The Paddington Alcohol Test (PAT) has evolved over 15 years as a clinical tool to facilitate emergency physicians and nurses giving brief advice and the offer of an appointment for brief intervention by an alcohol nurse specialist. Previous work has shown that unscheduled emergency department re-attendance is reduced by ‘making the connection’ between alcohol misuse and resultant problems necessitating emergency care. The revised ‘PAT (2009)’ now includes education on clinical signs of alcohol misuse and advice on when to request a blood alcohol concentration.

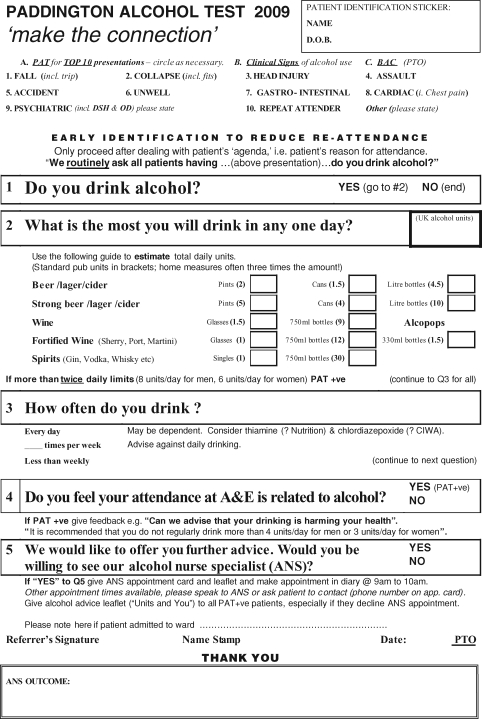

The Paddington Alcohol Test (PAT) has developed pragmatically for emergency department (ED) staff to give patients brief advice (BA) about alcohol since first published in 1996 (Smith et al., 1996). PAT is applied selectively for the 10 presenting conditions with the highest prevalence of alcohol misuse as a contributory factor (Fig. 1) (Huntley et al., 2001). BA includes the offer of an appointment with an alcohol nurse specialist (ANS) for an individualized, motivational enhancement-based session: brief intervention (BI). For every two patients accepting such an appointment, there is one less re-attendance over the next year (Crawford et al., 2004), justifying the time spent on initial BA. PAT (2009) (Fig. 2) distinguishes between BA delivered by any ED doctor or nurse taking 2 min or less, as opposed to specialized BI of >20 min delivered by ANSs.

Fig. 1.

PAT(2009) front: ‘make the connection’.

Fig. 2.

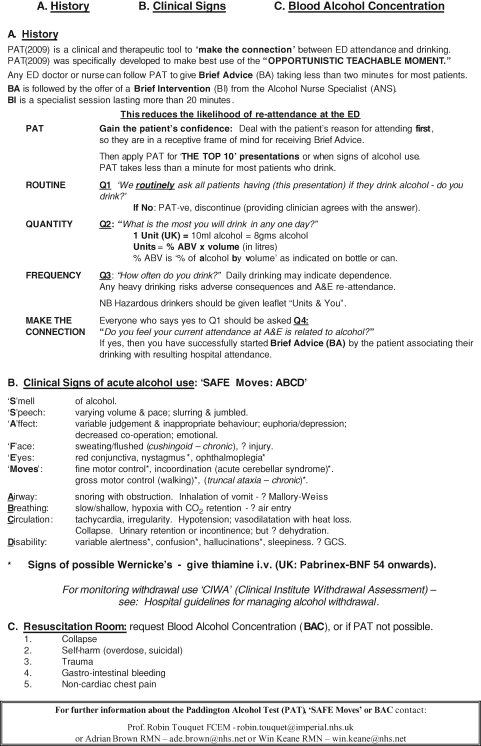

PAT(2009) reverse side: ‘History, Clinical signs, Blood Alcohol concentration (BAC)’.

The term ‘screening’ is replaced in PAT (2009) (Figs. 1 and 2) by ‘early identification’, to encourage patients’ insight before permanent alcohol-related harm has developed. The requirement to process 98% of ED patients within 4 h (Department of Health, 2001) creates its own stresses, but improved patient throughput generates increased gratitude from patients with an improved working atmosphere for staff. This helps counter ‘clinical inertia’—failure to initiate or intensify treatment when indicated.

ED staff are instructed to deal first with the patient's reason for attending—before introducing the subject of alcohol. The patient, responding to this initial care, is more likely to contemplate change when PAT is applied. The word routinely is included in the first question: ‘We routinely ask all patients who have (presenting condition), do you drink alcohol?’ This approach is non-judgemental, as are the second (quantity) and third (frequency) questions. The key fourth question is: ‘Do you feel your attendance at A&E is related to alcohol?’ This helps ‘make the connection’ facilitating the patient to contemplate change (Rollnick et al., 2005).

PAT (2009) (Fig. 2) summarizes clinical signs of alcohol use (acronym ‘SAFE Moves ABCD’), although these may be masked by tolerance (Cherpitel et al., 2005). Alcohol misuse itself and Wernicke's encephalopathy may both demonstrate similar clinical signs (Fig. 2). Therefore, Wernicke's can only be diagnosed when the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is low (Thomson et al., 2002). PAT (2009) highlights use of intravenous B vitamins (Pabrinex), especially when nutrition is poor (Joint Formulary Committee, 2007).

PAT (2009) delineates requesting of BACs where results can assist management and, when raised, prompt subsequent PAT application (Touquet et al., 2008). Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment (CIWA) guidelines are recommended for the recognition and prevention of alcohol withdrawal (Taylor, 2006).

Feedback to patients about their drinking increases BI appointment-uptake by 20%. PAT (2003) showed 97% sensitivity and 88% specificity by comparison to the ‘gold standard’ AUDIT questionnaire (Patton et al., 2004). Attendance for BI exceeds 50% if appointment is within 48 h of ED attendance (Brown, 2006). Dependent drinkers may need referral for further support in the community, which the ANS provides rather than ED physicians.

Alcohol education, by consultants, senior nurses and ANSs, is facilitated by PAT (2009). While it may take time to gain staff confidence that implementing PAT is worthwhile, it is welcome once reduction in alcohol-related re-attendance is realized. Each acute hospital should now have a named Consultant as ‘Alcohol Lead’.

References

- Brown A. Alcohol health work, an opportunist A&E intervention. Clin Eff Nurs. 2006;9S3:e253–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel C, Bond J, Ye Y, et al. Clinical assessment compared with breathalyser readings in the emergency room: concordance of ICD-10 Y90 and Y91 codes. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:689–95. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.016865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MJ, Patton R, Touquet R, et al. Screening and referral for brief intervention of alcohol misusing patients in an emergency department: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1334–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . Reforming Emergency Care. London: HMSO; 2001. Available at www.doh.gov.uk/emergencycare. (1 March 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- Huntley JS, Blain C, Hood S, et al. Improving detection of alcohol misuse in patients presenting to an A&E department. Emerg Med J. 2001;18:99–104. doi: 10.1136/emj.18.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Formulary Committee . British National Formulary (BNF, bnf.org), 54th edn. 2007. p. 515. [Google Scholar]

- Patton R, Hilton C, Crawford MJ, et al. The Paddington Alcohol Test: a short report. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:266–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Butler CC, McCambridge J, et al. Consultations about changing behaviour. BMJ. 2005;331:961–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7522.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SGT, Touquet R, Wright S, et al. Detection of alcohol misusing patients in accident and emergency departments: the Paddington alcohol test (PAT) J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13:308–12. doi: 10.1136/emj.13.5.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B. Implementation and clinical audit of alcohol detoxification guidelines. B J Nurs. 2006;15:30–7. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2006.15.1.20307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AL, Cook CCH, Touquet R, et al. The Royal College of Physicians Report on Alcohol: guidelines for managing Wernicke's Encephalopathy in the A&E department. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:513–21. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.6.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touquet R, Csipke E, Holloway P, et al. Resuscitation room blood alcohol concentrations: one-year cohort study. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:752–6. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.062711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]