Abstract

Object

Angiocentric glioma was recently recognized as a distinct clinicopathological entity in the 2007 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. The authors present the first 3 pediatric cases of angiocentric glioma encountered at their institution and review the literature of reported cases to elucidate the characteristics and outcomes of pediatric patients with this novel tumor.

Methods

The children in the 3 cases of angiocentric glioma were 10, 10, and 13 years old. Two presented with intractable seizures and 1 with worsening headache and several months of decreasing visual acuity. Twenty-five cases, including the 3 first described in the present paper, were culled from the literature.

Results

In all 3 cases, MR imaging demonstrated a superficial, nonenhancing, T2-hyperintense lesion in the left temporal lobe. Histologically, the tumors were composed of monomorphous cells with a strikingly perivascular orientation that were variably reactive for glial fibrillary acidic protein and epithelial membrane antigen. Surgical treatment resulted in gross-total resection in all 3 cases. By 24, 9, and 6 months after surgery, all 3 patients remained seizure free without focal neurological deficits.

Conclusions

Among 25 cases of angiocentric glioma, seizure was the most common symptom at presentation. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated supratentorial, nonenhancing, T1-hypointense, T2-hyperintense lesions. Gross-total resection of this lesion yields excellent results.

Keywords: angiocentric glioma, low-grade glioma, pediatric neurosurgery

Angiocentric glioma, recently codified as a new brain tumor type in the 2007 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System,1,4 was first identified in 2005 in 2 independent and nearly simultaneous reports.3,8 Since then, only 3 reports5–7 have detailed the unique clinical, radiographic, and histopathological features of this lesion. In these early reports authors suggested that angiocentric gliomas are slow-growing supratentorial tumors radiographically similar to other low-grade astrocytomas and that children and young adults often present with seizures. The defining histological feature of this entity is its striking perivascular pattern of growth. Although tumor cells diffusely infiltrate tissue, they tend to cluster around vessels in a manner emulating the pseudorosettes of ependymoma and astroblastoma. Characteristic “dot-like” EMA staining of microlumens within these tumors is further evidence of the ependymomatous differentiation of lesion cells. The neoplasm is variably immunoreactive for GFAP.

The paucity of clinical data on angiocentric gliomas limits our understanding of the presentation, treatment, and clinical course in cases of this novel entity. Here, we present the first 3 pediatric cases of angiocentric glioma encountered at our institution and review the literature on all previously reported cases to date. Thus, in this paper we provide the first clinical review of angiocentric gliomas, and more importantly we distinguish this recently recognized pathological entity from other supratentorial gliomas in the pediatric population in terms of presentation and outcome and suggest that by performing GTR of the tumor, angiocentric gliomas have a more favorable prognosis compared with seizure-associated gliomas in children previously described.

Illustrative Cases

Case 1

History and Examination

This 10-year-old, left-handed, hearing-impaired boy presented with a 1-year history of headaches, difficulty concentrating, shortening attention span, decreasing visual acuity from 20/20 to 20/80, and hearing loss of 10 dB. Otherwise, the child had no focal or lateralizing neurological deficits.

An MR image initially revealed a left-sided nonenhancing posterior temporal lesion (T1 hypointense, FLAIR hyperintense), which was radiographically monitored at 6-month intervals. Two years after his initial presentation, an MR imaging study demonstrated some increase in the FLAIR signal size of the lesion with a peripherally based 1 × 1–cm cystic lesion in the left inferior temporal lobe (Fig. 1).

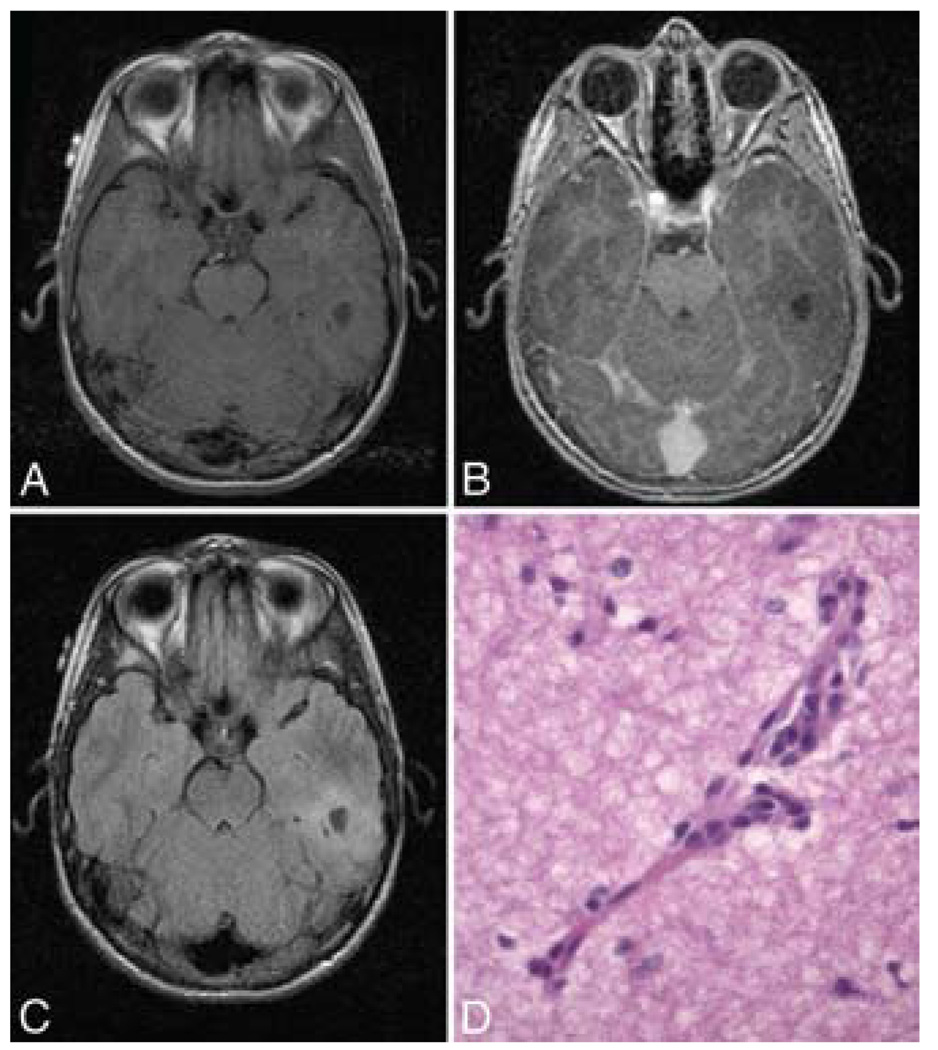

FIG. 1. Case 1.

A: Axial T1-weighted MR image without contrast demonstrating a peripherally based cystic lesion in the inferior left temporal lobe. B: Axial T1-weighted MR image with contrast showing the same lesion that appears in panel A. C: Axial FLAIR MR image obtained at the same level, revealing another perspective. D: Photomicrograph showing individual tumor cells with elongated nuclei diffusely infiltrating the brain parenchyma. However, they cluster around vessels, including the small capillary in the center of the field. Both EMA and GFAP immunohistochemical stains were negative—as they sometimes are in this pathological entity. H & E, original magnification ×400.

Operation

The patient was taken to the operating room where a left temporal craniotomy was performed for resection of the tumor. The surgeon noted that the tumor was discolored and semi-firm in texture. It was easily differentiated from surrounding edematous brain. Intraoperative frozen histological analysis suggested low-grade glioma.

Postoperative Course

At the final histological assessment, the perivascular orientation of tumor cells was typical of an angiocentric glioma. The final pathological diagnosis was low-grade neoplasm consistent with angiocentric glioma (Fig. 1). Postoperative MR images revealed total resection of the tumor.

By 24 months after surgery, the patient was doing well without headaches or focal deficits. He remains seizure free and is taking no medications. There has been no clinical or radiological evidence of tumor progression during this 24-month postoperative period.

Case 2

History and Examination

This 10-year-old, right-handed boy with intractable epilepsy was referred for neurosurgical evaluation after EEG documentation of a left frontotemporal seizure focus. He had febrile seizures as an 18-month-old infant, and complex partial seizures developed at 8 years of age. The seizures, consisting of episodes of stomach sensation, speech arrest, and blank stares, occurred ~ 3–4 times per week. He did not experience headaches or localizing neurological deficits.

At the time of a neurosurgical evaluation, an MR image revealed a stable cystlike lesion comparable to that seen on several prior radiographic studies. More specifically, the MR image demonstrated a nonenhancing left temporal cystic lesion (T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense) overlying the left middle and inferior temporal gyri and measuring 1.5 × 2.6 × 2.5 cm (Fig. 2). There was no evidence of hippocampal abnormalities, heterotopic gray matter, or mass effect. The differential was a cystic lesion with scalloping of the temporal bone.

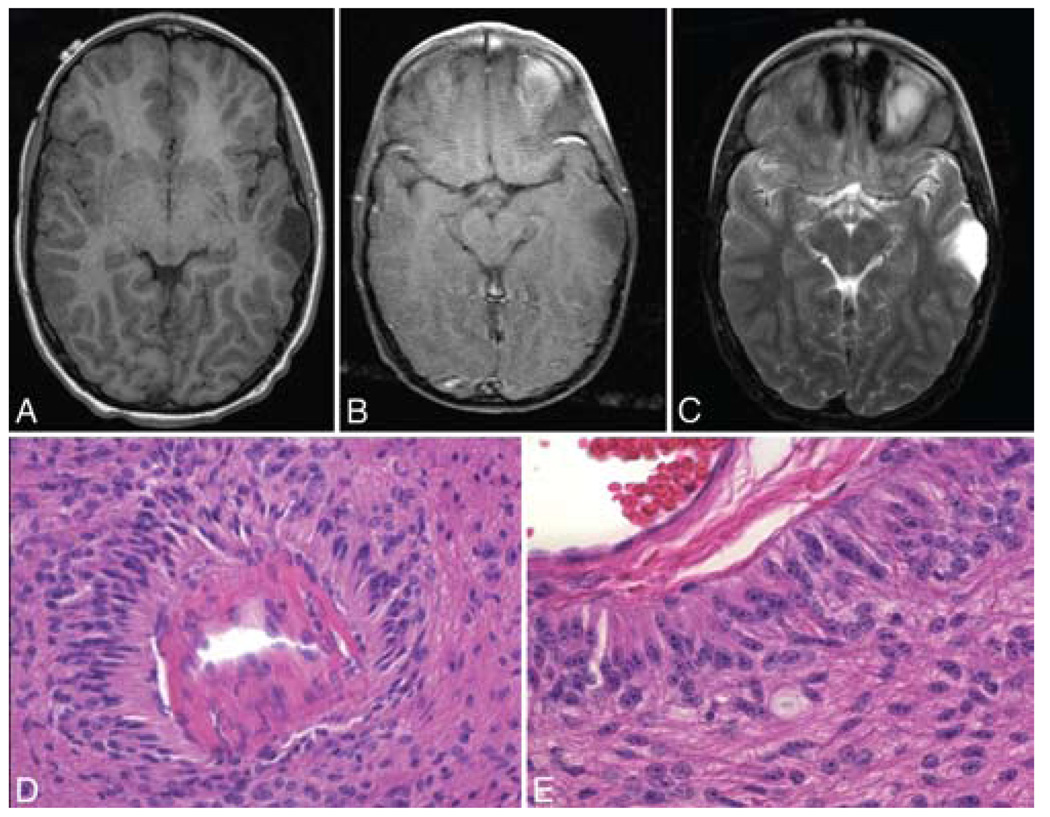

FIG. 2. Case 2.

A: Axial T1-weighted MR image without contrast showing an extraaxial cystic lesion in the left temporal lobe. B: Axial T1-weighted MR image with contrast revealing the same lesion, which is nonenhancing. C: Axial T2-weighted MR image obtained at the same level, demonstrating the hyperintense tumor signal. D: Photomicrograph displaying tumor cells that form striking pseudorosette type structures around cerebral vessels. E: Photomicrograph showing tumor cells in subpial locations arranged in radial arrays perpendicular to the pial surface. H & E, original magnification × 100 (D) and × 160 (E).

Operation

The patient subsequently underwent left craniotomy for placement of multiple subdural strips, grids, and depth electrodes for invasive EEG monitoring. At the time of this initial surgery, the lesion was not cystic but rather more of a gelatinous soft tumor. The plan for a 2-stage procedure remained, given that our goal was seizure control and that the preoperative image was not suggestive of an intraaxial tumor. The epileptogenic focus was indeed the tumor, with some occasional spikes 1 cm away from the lesion.

The patient returned for grid removal and underwent a GTR of the left temporal lesion and the surrounding epileptogenic focus. Based on the initial biopsy procedure, a low-grade glioma was diagnosed, but an unusual architecture with CD34-positive vessels in the center of papillary structures was noted. The subsequent resection specimen showed striking perivascular organization and subpial palisading (Fig. 2). The infiltrating tumor cells were GFAP positive and EMA immunohistochemical staining demonstrated tiny, dotlike microlumens (Fig. 3). All of these features supported a diagnosis of angiocentric glioma.

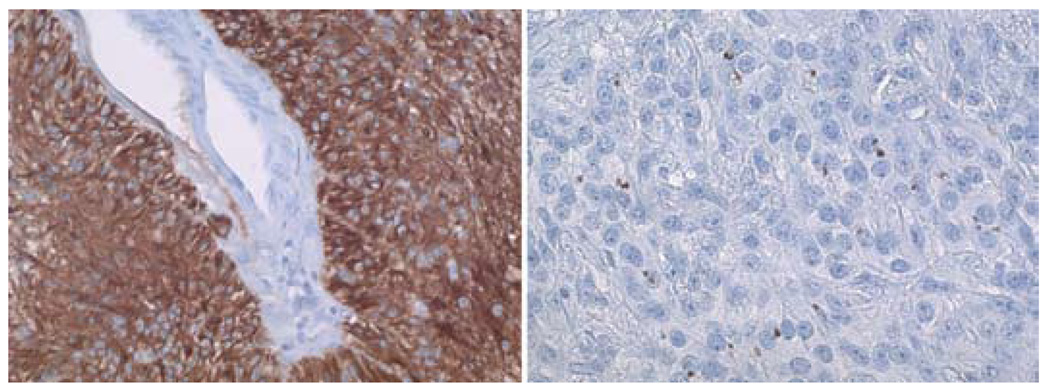

FIG. 3. Case 2.

Photomicrographs demonstrating results of GFAP and EMA immunohistochemical staining. Left: Glial fibrillary acidic protein is present diffusely within the neoplastic cells clustering around a vessel in the center of the image. Right: Although not present in all angiocentric gliomas, dotlike immunohistochemical staining for EMA confirms the diagnosis. The dotlike pattern corresponds to tiny intracellular microlumens that can also be demonstrated using electron microscopy. Original magnification ×100 (left) and × 160 (right).

Postoperative Course

By his 9-month follow-up visit, the patient remained seizure free, without word-finding difficulties, visual disturbances, or weakness. An MR imaging study revealed no tumor recurrence. The patient remains in school with an improving performance compared with previous years, and he is seizure-free while on carbamazepine and levetiracetam. These medications are being tapered off by the epilepsy service.

Case 3

History and Examination

This 13-year-old, right-handed girl with a prolonged history of absence seizures and headaches was referred for neurosurgical evaluation after EEG localization of a left temporal seizure focus that corresponded to a 2.4 × 1.2–cm nonenhancing T2-hyperintense lesion on MR imaging of the left anterior temporal lobe. The patient also had a history of a sports-related head trauma without loss of consciousness or hospitalization as well as viral meningitis as an infant. She was an otherwise healthy, active teenager without any neurological deficits.

Another MR imaging study revealed a stable left anterior temporal lobe lesion (T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense) suggestive of a low-grade glioma (Fig. 4).

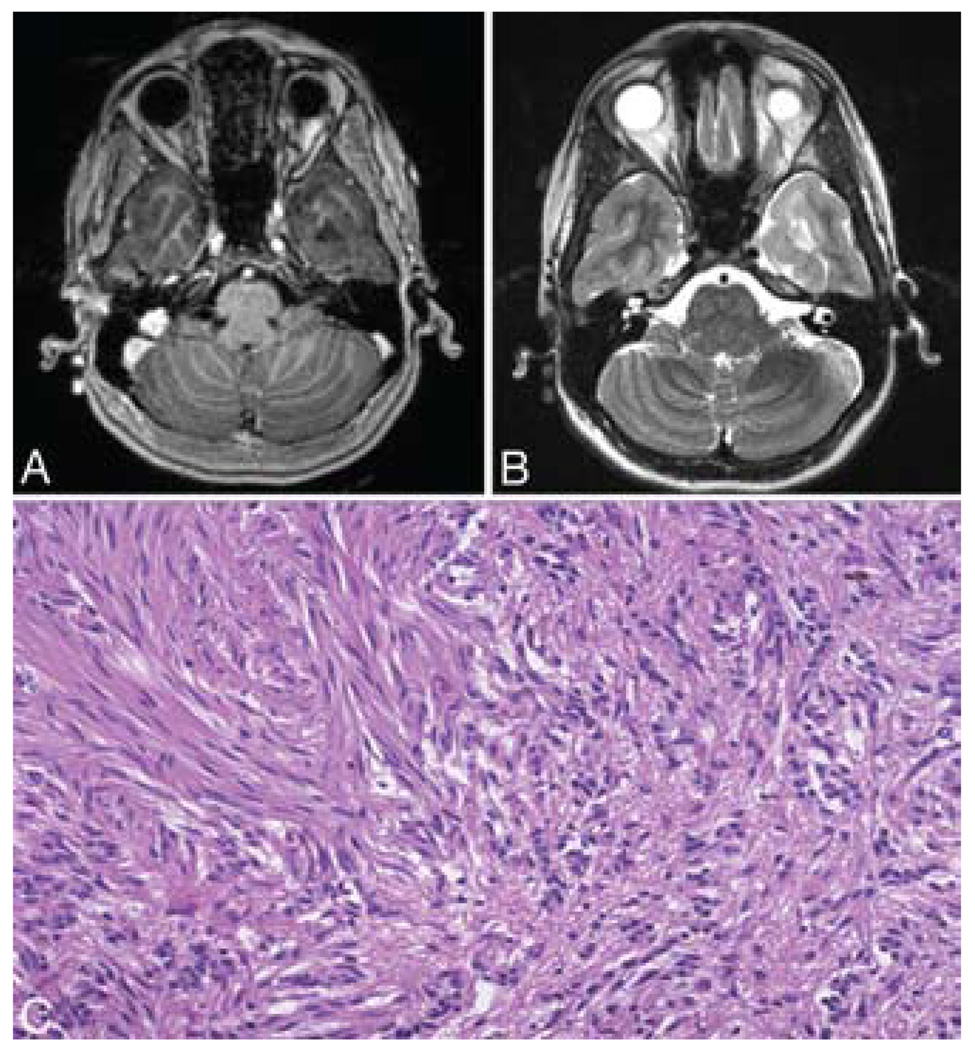

FIG. 4. Case 3.

A: Axial T1-weighted MR image with contrast showing a nonenhancing lesion in the left anterior temporal lobe. B: Axial T2-weighted MR image obtained at the same level, showing the hyperintense tumor signal. C: Photomicrograph displaying small clusters of monomorphous cells in the right side of the panel in opposition to more densely packed fascicles of elongated tumor cells in the left side of the panel. This pattern, which is reminiscent of a schwannoma, frequently can be seen in these lesions. This pattern may be a source of diagnostic confusion given the size of the specimen. H & E, original magnification × 64.

Operation

Given the patient’s lack of medical seizure control, she underwent a craniotomy for resection of the lesion.

Postoperative Course

Histological evaluation of a specimen revealed typical angiocentrically arranged infiltrative cells. Immunohistochemical staining with EMA labeled microlumens. Note, however, that there were also juxtaposed areas of compact fascicles of elongated tumor cells (Fig. 4). This compact pattern of growth can sometimes be seen in these lesions. The Ki 67 proliferative rate was low—as would be expected in this low-grade entity. The final diagnosis was angiocentric glioma. Postoperative MR imaging confirmed a GTR and the expected postoperative changes.

At her 6-month follow-up visit, the patient was faring well without any seizures, headaches, or focal neurological deficits. She is back in school, has no activity restrictions, has remained seizure free, and is taking no medications.

Discussion

Our case series is composed of the first 3 patients surgically treated at our institution for angiocentric glioma, a newly established brain tumor type. Two of the patients, ages 10 and 13 years, presented with intractable seizures, and the other patient, 10 years old, presented with headaches and decreasing visual acuity. Magnetic resonance imaging studies with an added contrast agent showed focal, nonenhancing, T2-hyperintense lesions all located in the left temporal lobe. All 3 tumors were histologically defined by diffusely infiltrating monomorphous tumor cells with prominent perivascular clustering. Two of the 3 tumors were GFAP positive and contained characteristic EMA-positive microlumens. Surgical treatment of these focal tumors yielded excellent outcomes in all 3 patients, and for as long as a 24-month postoperative period in 1 patient. In cases of pharmacoresistant epilepsy, resection was 100% effective in seizure resolution.

Overall, our description of the clinicopathological features and outcomes of pediatric patients with angiocentric glioma is consistent with the few previously reported cases of this novel tumor type in children. The clinical findings in all reported pediatric cases of angiocentric glioma are summarized in Table 1. The age at surgery ranged from 2 to 14 years (median 6.5 years). Fourteen patients were male and 11 were female. Among the 25 documented pediatric cases of angiocentric glioma, 24 patients (96%) presented with intractable seizures. In all cases, the tumor was located supratentorially, with 10 in the frontal lobe, 8 in the temporal lobe, 6 in the parietal lobe, and 1 in the occipital lobe. Radiographic features exhibited in all cases included unifocality, T2 hyperintensity, and no enhancement with the addition of a contrast agent. Additionally, Lellouch-Tubiana et al.3 and Preusser et al.6 identified the cortical rim of hyperintensity on T1-weighted images (Cases 9–23) and the stalklike extension to the adjacent ventricle on T2-weighted images (Cases 9–18) as pathognomonic radiological features of angio-centric glioma. However, these characteristics were not seen on the MR images obtained in our patients. In 14 (56%) of the 25 cases in the literature, GTR of the tumor was achieved, and all patients remained seizure free without tumor recurrence. On the other hand, among the 9 cases (36%) with only STR of the tumor, 4 patients experienced a return of their seizures. One patient who underwent STR with radiation treatment as well as another patient who underwent a biopsy procedure and radiation therapy showed complete seizure resolution.

TABLE 1.

Literature review of studies on angiocentric gliomas*

| Authors & Year | Case No. | Age at Op (yrs), Sex | Presentation Symptoms | Tumor Location | Unique Features on MRI |

Treatment | FU(mos) | Seizure Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| present study | 1 | 10, M | headaches, decreasing visual acuity | lt posterior temporal lobe | none | GTR | 24 | no |

| 2 | 10, M | seizures | lt middle temporal lobe | none | GTR | 9 | no | |

| 3 | 13, F | seizures | lt anterior temporal lobe | none | GTR | 6 | no | |

| Wang et al., 2005 | 4 | 11, F | seizures | rt medial temporal lobe | none | GTR | 12 | no |

| 5 | 4, F | seizures | rt parietal lobe | none | GTR | 48 | no | |

| 6 | 3, M | seizures | lt occipital lobe | none | STR | 36 | no | |

| 7 | 10, M | seizures | rt inferior frontal lobe | none | GTR | 24 | no | |

| 8 | 3, F | seizures | rt inferior frontal lobe | none | STR | 24 | no | |

| Lellouch-Tubiana et al., 2005 | 9 | 4, F | seizures | lt anterior temporal lobe | T1, T2 | GTR | 168 | no |

| 10 | 6.5, M | seizures | lt frontotemporal lobe | T1, T2 | GTR | 168 | no | |

| 11 | 2, M | seizures | rt frontoparietal lobe | T1, T2 | STR | 36 | yes | |

| 12 | 4, F | seizures | lt medial temporal lobe | T1, T2 | GTR | 72 | no | |

| 13 | 4.5, M | seizures | rt parietal lobe | T1, T2 | GTR | 60 | no | |

| 14 | 9.5, F | seizures | lt frontal lobe | T1, T2 | GTR | 2.3 | no | |

| 15 | 13, F | seizures | rt orbitofrontal lobe, gyrus rectus, insula | T1, T2 | STR | 24 | yes | |

| 16 | 12, M | seizures | rt parietal lobe | T1, T2 | GTR | 24 | no | |

| 17 | 3, F | seizures | lt frontal lobe | T1, T2 | STR | 14 | yes | |

| 18 | 10, M | seizures | lt frontolateral lobe, premotor cortex | T1, T2 | STR | 12 | yes | |

| Preusser et al., 2007 | 19 | 6, M | seizures | medial temporal lobe | T1 | STR | 60 | no |

| 20 | 8, F | seizures | medial inferior temporal lobe | T1 | STR | 60 | no | |

| 21 | 3, M | seizures | precuneus | T1 | STR | 60 | no | |

| 22 | 12, F | seizures | precuneus | T1 | STR & radiation | 7 | no | |

| 23 | 14, M | seizures | frontoparietal lobe | T1 | small biopsy &radiation | 24 | no | |

| Sugita et al., 2008 | 24 | 6, M | seizures | rt occipitoparietal lobe | none | GTR | 9 | no |

| Lum et al., 2008 | 25 | 5, M | headaches, seizures | rt inferomedial posterior frontal lobe | none | GTR | unknown | no |

FU = follow-up; STR = subtotal resection; T1 = cortical rim of hyperintensity; T2 = stalklike extension to adjacent ventricle.

Nearly all of the patients in our series, as well as those in the reviewed cases, presented with seizures. This finding suggests that angiocentric glioma—as well as focal cortical dysplasias and glioneuronal tumors such as gangliomas and dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors—must be considered in the neurosurgical evaluation of medically refractory epilepsy in children and young adults.

Nonetheless, the presenting factors and outcome in cases of angiocentric gliomas are distinct among seizure-associated lesions in children. The median age at surgery for patients among the 25 cases was 6.5 years, compared with 9.9 years for children in the Göteborg epilepsy surgery series.2 The male/female ratio in our review was 14:11, versus 29:31 in the Göteborg series. The supratentorial distribution of angiocentric gliomas is varied, whereas epileptogenic foci are more commonly concentrated in the temporal lobe. Most patients with angiocentric gliomas (96%) present with seizures. Low-grade gliomas, however, accounted for only 8% of the histopathological diagnoses in the Swedish study and were associated with 66.7% seizure freedom by the 2-year follow-up. Postoperative seizure freedom in our review was 100% with GTR and 56% with STR at 2.3–168 months of follow-up.

Histopathologically, angiocentric glioma is firmly established as a unique entity, although its cytogenesis remains unclear. Whether from astrocytic and ependymal lineages, as posited by Wang et al.,8 or from radial glia or neuronal origins, as suggested by Lellouch-Tubiana et al.,3 this distinctive tumor has been commonly observed to behave as a low-grade neoplasm, thereby accounting for its excellent prognosis in all documented surgical cases. In fact, all cases involving GTR have resulted in seizure resolution and positive outcomes. Only in cases of STR has symptom recurrence been documented.

The recognition of angiocentric glioma, then, permits a diagnosis with a more favorable prognosis compared with other supratentorial gliomas characterized by seizures in children. Moreover, clinical analysis of the disease affirms that the extent of resection is likely the primary determinant of seizure-free survival in children with brain tumors.

Conclusions

Angiocentric glioma is a unique brain tumor that accounts for a portion of medically refractory epilepsy in children and young adults that is amenable to neurosurgical intervention. A compilation and assessment of the case reports published since the tumor’s original description yields the following conclusions: 1) seizure is the most common symptom at presentation; 2) MR imaging demonstrates a supratentorial, nonenhancing, T1-hypointense, T2-hyperintense lesion; 3) the tumors have characteristic pathological features; and 4) the outcome following treatment with GTR of the tumor is excellent.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- EEG

electroencephalographic

- EMA

epithelial membrane antigen

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GTR

gross-total resection

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

References

- 1.Brat DJ, Scheithauer BW, Fuller GN, Tihan T. Newly codified glial neoplasms of the 2007 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: angiocentric glioma, pilomyxoid astrocytoma and pituicytoma. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eriksson S, Malmgrem K, Rydenhag B, Jonsson L, Uvebrant P, Nordborg C. Surgical treatment of epilepsy—clinical, radiological and histopathological findings in 139 children and adults. Acta Neurol Scand. 1999;99:8–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1999.tb00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lellouch-Tubiana A, Boddaert N, Bourgeois M, Fohlen M, Jouvet A, Delalande O, et al. Angiocentric neuroepithelial tumor (ANET): a new epilepsy-related clinicopathological entity with distinctive MRI. Brain Pathol. 2005;15:281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lum DJ, Halliday W, Watson M, Smith A, Law A. Cortical ependymoma or monomorphous angiocentric glioma. Neuropathology. 2008;28:81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2007.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preusser M, Hoischen A, Novak K, Czech T, Prayer D, Hainfellner JA, et al. Angiocentric glioma report of clinico-pathologic and genetic findings in 8 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1709–1718. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31804a7ebb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugita Y, Ono T, Ohshima K, Niino D, Ito M, Toda K, et al. Brain surface spindle cell glioma in a patient with medically intractable partial epilepsy: a variant of monomorphous angiocentric glioma? Neuropathology. 2008;28:516–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2007.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M, Tihan T, Rojiani AM, Bodhireddy SR, Prayson RA, Iacuone JJ, et al. Monomorphous angiocentric glioma: a distinctive epileptogenic neoplasm with features of infiltrating astrocytoma and ependymoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:875–881. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000182981.02355.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]