Abstract

Trophic factors secreted both from the endocardium and epicardium regulate appropriate growth of the myocardium during cardiac development. Epicardially-derived cells play also a key role in development of the coronary vasculature. This process involves transformation of epithelial (epicardial) cells to mesenchymal cells (EMT). Similarly, a subset of endocardial cells undergoes EMT to form the mesenchyme of endocardial cushions, which function as primordia for developing valves and septa. While it has been suggested that transforming growth factor-βs (Tgf-β) play an important role in induction of EMT in the avian epi- and endocardium, the function of Tgf-βs in corresponding mammalian tissues is still poorly understood. In this study, we have ablated the Tgf-β type I receptor Alk5 in endo-, myo- and epicardial lineages using the Tie2-Cre, Nkx2.5-Cre, and Gata5-Cre driver lines, respectively. We show that while Alk5-mediated signaling does not play a major role in the myocardium during mouse cardiac development, it is critically important in the endocardium for induction of EMT both in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, loss of epicardial Alk5-mediated signaling leads to disruption of cell-cell interactions between the epicardium and myocardium resulting in a thinned myocardium. Furthermore, epicardial cells lacking Alk5 fail to undergo Tgf-β-induced EMT in vitro. Late term mutant embryos lacking epicardial Alk5 display defective formation of a smooth muscle cell layer around coronary arteries, and aberrant formation of capillary vessels in the myocardium suggesting that Alk5 is controlling vascular homeostasis during cardiogenesis. To conclude, Tgf-β signaling via Alk5 is not required in myocardial cells during mammalian cardiac development, but plays an irreplaceable cell-autonomous role regulating cellular communication, differentiation and proliferation in endocardial and epicardial cells.

Keywords: Tgf-β, signaling, epicardium, endocardium, heart development

Introduction

The heart is the first functional organ to develop in vertebrates. During gastrulation, cardiogenic mesodermal cells form the so called cardiogenic field, which subsequently gives rise to a linear heart tube composed of outer myocardial and inner endothelial layers (Anderson et al., 2003). After cardiac looping, cardiac neural crest cells migrate to the base of the aortic sac and form the aortico-pulmonary septum, which gradually separates the aorta from the pulmonary trunk (Hutson and Kirby, 2003). At the same time (around embryonic day 9.0–9.5 [E9.0 – E9.5]), a region between the developing atria and ventricles is specified to form an atrio-ventricular canal (AVC), an important structure making up the heart-valve inducing field(Eisenberg and Markwald, 1995). First the extracellular matrix rich in hyaluronic acid is deposited by the AVC myocardium followed by epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) of a subset of endocardial cells. The formed endocardial cushions will be further refined to form the AV valves and septa.

Soon after cardiac looping, a separate cell population derived from the hepatic primordium gives rise to the proepicardial cells near a venous pole of the developing heart (Bernanke and Velkey, 2002). Epicardial progenitor cells then dislodge as cellular vesicles, which spread out, and gradually cover the entire developing heart to form a coherent epicardium. A subpopulation of epicardial cells undergoes EMT and migrates into the subepicardial space rich in extracellular matrix proteins. It has been suggested that these transformed mesenchymal cells will produce cardiac fibroblasts and the vascular smooth muscle of the adult heart(Reese et al., 2002; Wada et al., 2003). Formation of coronary vasculature is essential once the myocardium becomes so thick that diffusion is not able to supply enough nutrients and oxygen to the heart.

A crucial function of Tgf-beta ligands during murine heart development was first suggested by the conventional knockout mice studies(Sanford et al., 1997). While Tgfb1−/− and Tgfb3−/− mice show no obvious signs of congenital heart defects(Kaartinen et al., 1995; Proetzel et al., 1995; Shull et al., 1992), Tgfb2−/− embryos display multiple cardiac defects(Sanford et al., 1997). These include the double-outlet right ventricle (DORV), which is known to derive from an error in development of the second heart field that contributes to formation of the outflow tract (OFT) myocardium. Tgfb2−/− mice display a defective myocardialization that is associated with a deregulation of neural crest cell apoptosis (Bartram et al., 2001).

Tgf-β signaling, which is predominantly mediated via a heterotetrameric receptor complex composed of two Tgf-β type II (TgfβRII) and two type I (Alk5) receptors, has also been implicated in induction of both endocardial and epicardial EMT(Brown et al., 1996; Jiao et al., 2006). Experiments on chick proepicardial organ and epicardial explant cultures have suggested that Tgf-β signaling via Alk5 is required for the loss of epithelial cell character of epicardial cells, while another type I receptor Alk2, known to mediate mainly Bmp signals, was shown to stimulate earlier proepicardial (PE) activation events(Compton et al., 2006; Olivey et al., 2006). Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that Tgf-β type III receptor (β-glycan), which binds Tgf-β2 with high affinity, is required for appropriate coronary vessel development in mouse embryos(Compton et al., 2007). Yet, the role of Tgf-βs in epicardial EMT, even in avians, is still controversial, since other studies have suggested that Fgfs are responsible of inducing epicardial EMT, while Tgf-βs would restrain their function (Morabito et al., 2001).

The Tgf-β type I receptor Alk5 was also recently shown to mediate endocardial transformation in the chick(Mercado-Pimentel et al., 2007). Interestingly, the murine Tgf-β type II receptor (TgfβRII, a prototypical binding partner of Alk5) was shown to be required for EMT in vitro, but not in vivo (Jiao et al., 2006). This discrepancy suggests that there is a mechanistic difference in Tgf-β signaling between avian and murine AVC transformation. Alternatively, it is possible that Alk5 can also interact with other members of the type II receptor family as recently suggested (Dudas et al., 2006). Other studies have demonstrated that Bmp2 is required both for specification of the AV canal myocardium and for endocardial EMT(Ma et al., 2005; Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006). However, it is currently not clear whether Bmp2-induced EMT in the AVC is mediated via Alk2 or Alk3, or whether they are both synergistically involved, since endothelial-specific abrogation of either Alk2 or Alk3 leads to a failure in EMT and severe defects in endocardial cushions in vitro and in vivo(Ma et al., 2005; Park et al., 2006; Song et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2005). Interestingly, deletion of Alk2 in endothelial cells not only attenuates phosphorylation of Bmp Smads 1/5/8, but also affects the activation of Tgf-beta Smads 2/3(Wang et al., 2005). Based on these studies, it is likely that Smad2/3 activation, and thus Alk5 signaling is also important for endocardial EMT in mammals.

In the present study we have analyzed the role of Alk5 during mouse heart development in vivo. Specifically, we deleted Alk5 in the endocardium, myocardium and in epicardium by using the Tie2-Cre, Nkx2.5-Cre and Gata5-Cre transgenic driver lines, respectively(Koni et al., 2001; Merki et al., 2005; Moses et al., 2001). We discovered that while Alk5 is redundant in cardiomyocyte development, it is needed in the endocardium for appropriate EMT both in vitro and in vivo, and for the subsequent endocardial cushion development. We show that in the epicardium Alk5 is required for epicardial-to-mesenchymal transformation in vitro, and for normal epicardial attachment and function in vivo. Moreover, our data indicate that disturbances in epicardial Alk5-mediated signaling lead to attenuated myocardial growth, defective formation of a smooth muscle cell layer surrounding coronary vessels and dramatic increase in a number of capillary vessels in the myocardium during late cardiac development.

Materials and Methods

Mice, genotyping, timed-matings and embryo isolation

All mice were maintained on mixed genetic backgrounds, and all studies were carried out at the Animal Care Facility of the Saban Research Institute in accordance with national and institutional guidelines. To generate endothelial-specific Alk5 mutants, Alk5FX/FX mice were crossed with Tie2-Cre driver mice (Koni et al., 2001), which were also heterozygous for the Alk5KO allele. The resulting compound heterozygotes for the Alk5FX and Alk5KO alleles, which also carry the Cre transgene (Alk5FX/KO/Tie2-Cre+/WT), have Alk5 specifically inactivated in endothelial cells (herein termed Alk5/Tie2-Cre), while the littermates with incomplete combinations (Alk5FX/KO/Tie2-CreWT/WT, Alk5FX/WT/Tie2-CreWT/WT and Alk5FX/WT/Tie2-Cre+/WT) of these alleles (which were all phenotypically indistinguishable from wild-type embryos) serve as controls. A similar breeding strategy was used to generate mouse mutants lacking Alk5 in the myocardium (Alk5/Nkx2.5-Cre) (Moses et al., 2001) and the epicardium (Alk5/Gata5-Cre) (Merki et al., 2005). Oligonucleotides for PCR-genotyping of the Alk5FX and for Alk5KO alleles as well as for Cre have been described elsewhere (Dudas et al., 2006). Tie2-Cre and Rosa26-reporter (R26R) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA); for detailed PCR-genotyping, see http://www.jax.org. Nkx2.5-Cre and Gata5-Cre mice have been previously described (Merki et al., 2005; Moses et al., 2001).

Histological analyses, R26 reporter assay and immunostaining

For histology, embryos were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 2–14 hours, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections (7–8 μm) were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin. Embryos and sections were stained for β-galactosidase activity as described(Hogan et al., 1994). For immunohistochemistry, fixed sections were stained with antibodies for WT1 (Santa Cruz Biotech.), N-cadherin (Invitrogen), ZO1 (Invitrogen), vascular smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (Biomedical Technologies Inc.) and Claudin-5 (Invitrogen). For VE-Cadherin, β-galactosidase and PECAM-1 immunostaining, tissues were processed for frozen sectioning followed by staining with corresponding antibodies (antibodies for VE-Cadherin, β-galactosidase and PECAM-1 were from BD-Pharmingen, MP Biochemicals and BD Pharmingen, respectively).

Apoptosis and cell proliferation

Apoptotic cells were detected in paraffin sections as a green fluorescence using DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL system (Promega). Cell proliferation was immunodetected using BrdU incorporation assay (Amersham). Briefly, pregnant females were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μl of Amersham BrdU labeling reagent. After 40 minutes, the female mice were euthanized with CO2, embryos were harvested, and processed for BrdU immunostaining according to the manufacturer’s instructions. BrdU-positive cells were detected with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated (green) secondary antibodies. Slides were counterstained with Propidium Iodide. For BrdU/MF20 double labeling, cells were first stained for BrdU as outlined above followed by labeling for sarcomeric myosin heavy chain using mouse monoclonal MF20 primary antibody followed by Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-mouse IgG2b secondary antibody (invitrogen) (Redfield et al., 1997). Slides were counterstained with DAPI. Positively stained cells were counted manually in defined areas of tissues. Statistical analysis of cell counts in serial sections and comparison of mutant specimens with controls was performed using a nonparametric Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test.

Epicardial and AVC canal explant cultures

Epicardial cultures were established as described (Chen et al., 2002). Some mutant and control cultures were treated with 10ng/ml of human recombinant hrTgf-β3 (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) for 24 hours. Both treated and untreated cultures were fixed with 2% formaldehyde for 15 minutes, and stained with anti-ZO1 antibody (Invitrogen) for the presence of the tight junction protein, zonula occludens and with FITC-phalloidin (Sigma Chemical Co.) for the presence of filamentous actin (f-actin). For AVC explant cultures, collagen gels (1mg/ml, type I rat tail collagen from BD) were prepared in OptiMEM supplemented with 1% fetal calf serum, 1xITS (insulin, transferrin and selenium) and penicillin/streptomysin (1x) all from Invitrogen(Sugi et al., 2004). AV regions of the hearts were dissected from E10 embryos, cut longitudally to expose the lumen and placed on the collagen gels. Additional media was added to the cultures 2 hours later and incubation was continued under standard tissue culture conditions (37°C, 100% humidity, 8% CO2).

RT-PCR and real-time PCR analyses

RNAs from ventricles were extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Omniscript RT (Qiagen) was used to generate cDNA from 1 μg of RNA. The PCR reactions were performed using platinum Tag polymerase (Invitrogen). The following pairs of primers were used:

| Fgf1: | sense, 5′ATGGCTGAAGGGGAGATCACAACC3′ |

| antisense, 5′CCTTCGGTGTCCATGGCCAAG3′ | |

| Fgf7: | sense, 5′TCTGCTCTACAGGTCATGCTTCCACC3′ |

| antisense, 5′CCCCTCCGCTGTGTGTCCATT3′ | |

| Fgf9: | sense, 5′AGGTGAAGTTGGGAGCTATTTCGGTG3′ |

| antisense, 5′TGTCCACACCGCGAATGCTGA3′ | |

| Fgf10: | sense, 5′TGGATACTGAGACATTGTGCCTCAGC3′ |

| antisense, 5′TTGCCCTGCCATTGTGCTGCCA3′ | |

| β-actin: | sense, 5′GTGGGCCGCTCTAGGCACCAA3′ |

| antisense, 5′CGGTTGGCCTTAGGGTTCAGGG3′ |

Real-time PCR was carried out with a ABI 7500 Real Time PCR system using the Applied Biosystems Taqman Universal Master mix (Roche) and universal probe/primer sets for the Fgf9 gene [mouse universal probe #60 (Roche). Left primer 5′TGCAGGACTGGATTTCATTTAG3′, and right primer 5′CCAGGCCCACTGCTATACTG3′]. Relative quantification of gene expression between samples was performed using the ABI 7500 Software v2.0.

Results

Tgf-β signaling via Alk5 is required in endothelial but not in myocardial cells for appropriate cardiac development

To analyze the role of Alk5 in endothelial and myocardial cells in vivo, we deleted the Alk5 gene in these cell types by crossing mice carrying the floxed Alk5 allele (Alk5FXFX) with double heterozygote Alk5KOWT/Tie2-Cre+/− and Alk5KOWT/Nkx2.5-Cre+/− mice, respectively(Koni et al., 2001; Moses et al., 2001). First we verified that the Tie2-Cre transgene is able to induce efficient recombination of the floxed Alk5 gene in the AV canal by using the RT-PCR analysis and primers with target sequences flanking the floxed exon 3 (Fig. 1A). The wild-type sample demonstrated a single band of an expected size (399 bp), while the mutant demonstrated a predominant amplification product of 156-bp representing a product of the recombined allele. This shows that the Alk5 gene is predominantly expressed by endothelial cells, and that the floxed allele of this gene is effectively recombined by Tie2-Cre in vivo. While close to the expected 25% of mutant embryos (Alk5/Tie2-Cre) were alive at E12 (n=10), they died soon after E13 with severe hemorrhaging in several organs including the brain and thoracic cavity (Fig 1B) (n=6). This is consistent with the endothelial cell-specific expression of the Tie2-Cre transgene. In contrast, abrogation of Alk5 in the entire myocardium using the well-characterized Nkx2.5-Cre driver line(Moses et al., 2001) did not reveal any obvious detectable cardiac phenotypes at E15 (Fig. 1C; n=3) or at E17 (data not shown). This result is in concordance with findings reported in a recent study demonstrating that cardiac development is not seriously affected in mice lacking the Tgf-β type II receptor, a predominant binding partner of Alk5, in the myocardium (Jiao et al., 2006).

Fig. 1. Deletion of Alk5 in endothelial and myocardial cells.

A, The floxed Alk5 gene is efficiently recombined in AVC tissues harvested at E10.0. RT-PCR using primers specific for sequences in exons 2 and 4 (blue arrowheads) demonstrates that the floxed exon 3 (yellow) is deleted in Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants (a 156-bp PCR product), while the wild-type sample displays an expected 399-bp fragment. B, Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants display severe cranial and thoracic bleeding (middle, black arrowheads) when compared to controls (left) at E12. Moreover, some Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants demonstrate severe cardiac edema (right, white arrow) indicative of a cardiac failure. High-power image has been shown in the inset. C, Deletion of Alk5 in myocardial cells using the Nkx2.5-Cre driver line does not reveal any major cardiac phenotypes in Alk5 mutants (right) when compared to controls (left). Two levels have been shown from rostral (top row) to caudal (bottom row). LV, right ventricle; RV, ventricle; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; PT, pulmonary trunk; Ao, aorta.

Tgf-β signaling via Alk5 in the endocardium is required for normal atrio-ventricular cushion development

Histological analysis of Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutant embryos at E10.0 indicated that the endocardial cushions in the AVC were grossly hypoplastic, displaying a notable reduction in a number of cells in the cushion mesenchyme (Fig. 2A–C). Although both superior and inferior cushions were severely affected, the number of mesenchymal cells in the inferior cushions was even more dramatically reduced at E11.0 (Fig. 2C). Using the R26R lineage tracing assay at E11.0, we show that although the endocardium in mutant samples stains strongly positive for lacZ, there are very few, if any, positively staining cells in the mesenchyme (Fig. 2D–E). Next we used a well-validated explant culture system to analyze whether endocardial cells lacking Alk5 would undergo EMT when cultured on 3-dimensional collagen gel (Fig. 2F–H). While the control samples displayed a large number of spindle-shaped cells penetrating the collagen gel, mutant cultures failed to demonstrate similar migration. To conclude, these analyses reveal that AVC explants harvested from Alk5/Tie2-Cre-deficient embryos failed to undergo EMT both in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 2. Defective EMT, cushion development and myocardium in Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants.

While control AVC cushions display a large number of mesenchymal cells at E10 (A, arrow), the mutant littermate shows no or very few mesenchymal cells (*) in AVC cushions (B). C, Statistical comparison in a number of mesenchymal cells between controls (C) and mutants (M) at E10 and E11. n=5, 5 sections per sample scored; SC, superior cushion; IC, inferior cushion; *, p<0.05. The R26R lineage tracing analysis shows that a large number of mesenchymal cells in controls is derived from the endocardium at E11 (D, arrow), while the cushions of the mutant littermate displays only very few blue cells of endothelial cell origin (E, arrow). The AVC explants harvested from controls display a large number of fibroblastoid-like cells (F, arrowheads) that migrate into the collagen gel, while in Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants there are no similar cells (*) detected (G). The histogram (H) depicts the statistical comparison between control and mutant cultures (*, p<0.05; n=5). At E12, the mutant samples (J, L) show the thinner myocardium and poor trabelucation when compared to controls (I, K; arrowheads depict the trabeculated myocardium; * in K illustrates the ventricular septum; arrowhead in L depicts the ventricular septum). The Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants demonstrate a clear attenuation in cell proliferation in the compact myocardium (hatched line in M and N) as demonstrated using BrdU incorporation assay and comparison between control and mutant littermates (M, N; green=BrdU-positive cells; red=MF20-positive myocardial cells). The histogram (O) illustrates quantification of BrdU positive cells in controls and in Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants (n=5 in each genotype; 5 sections per sample were scored; *, p<0.05).

Defective myocardium in mice lacking Alk5 in the endocardium

Histological analysis of samples harvested at E12 revealed that the myocardium was poorly trabeculated and much thinner in Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants than in controls (I-L). Moreover, the myocardium the interventricular septum was poorly developed. At E12, the mutant AVC cushions were still much smaller than controls, although they occasionally displayed a slightly better formed mesenchyme indicative of partial recovery (Fig. 2L). In contrast, the outflow tract cushions were rather well formed in Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants (Fig. 2J). BrdU incorporation and TUNEL assays demonstrated that the thin myocardium in Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants resulted from a defective myocardial proliferation (Fig. 2M–O) rather than from increased apoptosis (data not shown). Double staining for sarcomeric myosin heavy chain (MF20) and BrdU indicated that more than 97% of the BrdU-positive cells were of myocardial origin. It is noteworthy that the inappropriately thin myocardium was not reported in Tgfbr2/Tie2-Cre mutants (Jiao et al., 2006), which suggests that Alk5 mediates a broader spectrum of signaling events than its prototypical binding partner, Tgf-βRII in endocardial cells, as in neural crest cells (NCCs).

Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants display ventral body wall and cardiac defects

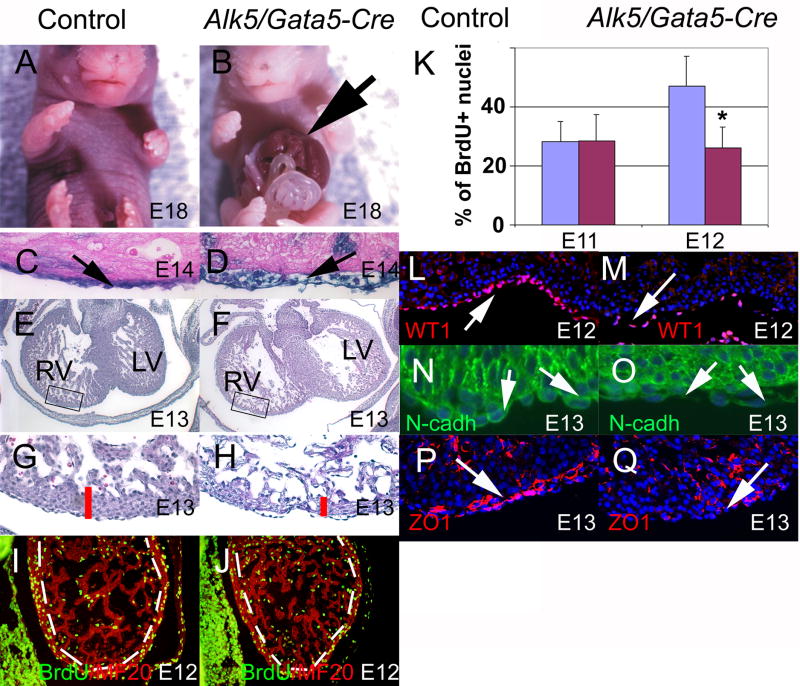

To analyze the role of Alk5 in the epicardium, we opted to use the Gata5-Cre transgenic mouse line that was recently shown to be an efficient inducer of Cre-mediated recombination in the PEO and in the epicardium (Merki et al., 2005; Zamora et al., 2007). The Gata5-Cre transgene-induced recombination becomes detectable around E9.0 in the ventral ectoderm and can be later seen in the developing liver and also in the pulmonary epithelium (data not shown). We crossed the Gata5-Cre mice (Merki et al., 2005) that were heterozygous for the Alk5 knockout allele (Alk5+/−) with mice homozygous for the floxed Alk5 (Alk5FX/FX) allele (Larsson et al., 2001). When the embryos were harvested at E18, the expected 25% of mutant embryos could be recovered (n=6). All the mutant embryos displayed a ventral body wall closure defect, gastroschisis (Fig. 3A, B), as demonstrated by the obvious extrusion of visceral organs through the ventral body wall. However, the lungs and heart were normally positioned in the thoracic cavity. A R26R lineage tracing assay at E14 demonstrated that the heart was covered by lacZ-positive epicardial cells both in controls and in Alk5 mutants suggesting that signaling via Alk5 is not needed for the formation of the proepicardium, the migration of proepicardial cells and the actual formation of the epicardium (Fig. 3C–D). However, we noticed that in all of the mutant embryos analyzed (n=5), the epicardium was inappropriately detached from the surface of the myocardium (Fig. 3D). Moreover, in transverse histological sections through the thorax at E13, both the compact and trabecular myocardium of Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants appeared thinner than those of controls (Fig. 3E–H). While we did not detect any apoptotic myocardial cells in mutants or in controls (data not shown), BrdU incorporation assay at E13 revealed that cell proliferation was significantly decreased in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants when compared to controls (Fig. 3I–K). Immunostaining for the epicardial marker WT1 demonstrated that the abnormally thin and poorly attached epicardium is clearly noticeable already at E12 (Fig. 3L–M), while at E11, we could not detect any differences between controls and mutants (data not shown). A similar bubbling epicardium and thin myocardium has also been described in mouse embryos lacking the Ca2+ -dependent cell adhesion molecule, N-cadherin, in neural crest cells (Luo et al., 2006). Interestingly, these embryos also demonstrated a notable downregulation of N-cadherin in epicardial cells. Since it is likely that appropriate epicardial-myocardial cell-cell interactions play an important role in generation of proper proliferative signals from the epicardium, and that cell adhesion molecules play a major role in maintenance of these interactions, we compared N-cadherin and the tight junction protein, ZO1 between controls and Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants. Our experiment show that N-cadherin was down-regulated in the epicardium of Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants (Fig. 3O) when compared to that of controls (Fig. 3N). Moreover, the control epicardium stained strongly positive for ZO1, not only in cell-cell junctions, but interestingly also in the basal surface and also in the subepicardial space, whereas mutants displayed decreased staining (Fig. 3P–Q). To conclude, our results demonstrate that while Alk5-mediated signaling is not needed for epicardial formation per se, it is likely required for appropriate epicardial attachment, which in turn is a prerequisite for appropriate myocardial proliferation.

Fig. 3. Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants display defects in the ventral body wall, epicardium and myocardium.

Ventral body wall fails to fuse in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants (arrow in B) at E18; A = control littermate. The epicardium of Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants (D) is abnormally loosely attached to the myocardium (blue staining cells; R26R assay). The control (C) demonstrates the normal epicardial morphology. The compact myocardial layer is abnormally thin in Alk5/Gata-Cre mutants (F, H), while controls (E, G) display a normal compact myocardial layer. Rectangular boxes in E and F depict the area shown in high power images in (G and H). At E12, the compact myocardium (hatched line) of Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants shows decrease in a number of BrdU-positive cells (green nuclei in J) when compared to controls (I). Immunostaining for MF20 was used to identify myocardial cells (red staining in Fig. I–J). Statistical analyses of cell proliferation (K) show that at E11 there are no differences in cell proliferation in the compact myocardium between controls and Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants (BrdU incorporation assay), while at E12 the number of proliferating cells in mutants is significantly decreased (*, p<0.05) in mutants when compared to controls (controls, blue columns; mutants, red columns). At E12 the WT1-positive epicardial cell layer is abnormally thin in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants and appears detached from the myocardium (M, white arrow) when compared to corresponding controls (L, white arrow). At E13 epicardial cells of Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants display an attenuated expression of N-Cadherin (O) and ZO1 (Q) when compared to corresponding control specimen (N, P). Arrows in L and N point to a positive signal in controls, and to reduced (M) or absent (O) signal in mutants.

Alk5 deficient epicardial cells fail to undergo EMT when stimulated by Tgf-β in vitro

Next we established epicardial cultures from control and Alk5/Gata5-Cre embryos at E12 (Chen et al., 2002), and after 24 hours in culture, stimulated them with 10 ng/ml of hrTgf-β3 (Fig. 4). Both control and Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutant epicardial cells (without Tgf-β stimulation) stained strongly positive for the tight junction marker ZO1 (red) and displayed f-actin (green) predominantly in cell-cell junctions (Hordijk et al., 1997) (Fig. 4A–B). Control cultures treated with Tgf-β3 displayed a pronounced loss of ZO1 from tight junctions, and an obvious formation of stress fibers typically seen in fibroblastoid cells (Fig. 4C). In contrast to controls, cells lacking Alk5 did not show detectable changes in reorganization of actin cytoskeleton or in dissolution of tight junctions after Tgf-β3 treatment (Fig. 4D). These analyses demonstrate that signaling via Alk5 is required for successful epicardial transformation in vitro.

Fig. 4. Epicardial EMT fails in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants in vitro.

Control and Alk5/Gata5-Cre epicardial cell cultures were established from E12 embryos and stimulated with Tgf-β3 (10 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Unstimulated cultures [both control (A) and mutant (B)] displayed positive ZO1 (red) and FITC-Phalloidin (green) staining in cell-cell junctions consistent with an epithelial phenotype. Control cultures stimulated with Tgf-β3 showed a noticeable loss of ZO1 from cell-cell borders and a robust formation of actin stress fibers (C), while mutant cultures failed to display comparable phenotypic changes (D).

Myocardial vascularization in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants

To analyze whether the lack of Alk5-mediated signaling in the epicardium would lead to defective coronary vessel development, we stained both the control and Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutant hearts for the endothelial cell marker PECAM-1 at E13 and E15. Both controls and Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants formed a similar vascular subepicardial network (Fig. 5A, C). Similarly, analysis of freshly dissected mutant embryos at E18.0 did not reveal any obvious macrosopic coronary vessel abnormalities (Fig. 5B, D). Serial sectioning from rostral to caudal demonstrated that both the right and left coronary ostia and coronary arteries are histologically comparable between controls and mutants at E17 (Fig. 5E–L, and data not shown). However, mutant coronary arteries demonstrated much weaker staining for vascular smooth muscle myosin suggesting defective development of smooth muscle cell layer surrounding the coronary arteries (Fig. 5M–N). Moreover, a histological analysis at E18 revealed that the myocardium appeared to contain more small blood-filled vessels in mutants than in controls (Fig. 6A–B).

Fig. 5. Coronary vessels develop, but fail to demonstrate appropriate smooth muscle cell differentiaton in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants.

PECAM-1 whole mount staining reveals a comparable vascular plexus between controls (A) and mutants (C) at E15. Freshly mounted hearts at E18 show no differences between coronary arteries (arrows in B and D) in control (B, dorsal view) and Alk5/Gata5-Cre (D, dorsal view) embryos. Serial sectioning (rostral to caudal) shows no obvious abnormalities in the coronary ostia (E, G, arrows) and coronary arteries (F, H, I–L, arrows) in mutants (G, H, K, L) when compared to controls (E, F, I, J). Immunostaining for vascular smooth muscle myosin demonstrates a well-formed smooth muscle cell layer surrounding the coronary arteries in controls (M), but not in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants (N). Ao, aorta; LCA, left coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

Fig. 6. Abnormal myocardial capillary vasculature in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants.

Alk5/Gata-Cre mutants (B) display a higher number of myocardial blood vessels (arrows) than control littermates (A) as demonstrated by H&E staining at E17. Immunostaining for PECAM-1 (C, D), Claudin-5 (E, F), ZO1 (G, H) and VE-Cadherin (I, J) show more intense myocardial staining in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants (arrows in D, F, H and J) than in controls (C, E, G and I). Samples for PECAM-1 staining were collected at E18, while samples for all other stainings were harvested at E17. However, the epicardium in mutants (arrow in J) did not stain for VE-Cadherin, while in controls the epicardium (arrow in I) demonstrated a strong positive staining. K, RT-PCR analysis demonstrates that at E16 Fgf9 is increased in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants (M1 and M2) when compared to controls (C1 and C2), while Fgf1, Fgf7 and Fgf10 are unchanged. C1 and C2, and M1 and M2 represent two independent control and mutant samples, respectively. Two-fold increase in Fgf9 expression was confirmed by real time PCR analysis (L) (Control, blue column; Mutant, red column; n=3).

To compare myocardial vascularization in more detail, we performed immunostaining for PECAM-1 (endothelial marker), Claudin-5 (a tight-junction marker for vascular endothelial cells), ZO-1 (a tight-junction marker) and VE-cadherin (marker for vascular endothelial cells) at E17 and E18. In controls, all these endothelial/epithelial markers stained the endothelial lining of the coronary vessels strongly, while the staining was relatively weak in other parts of the myocardium Fig. 6C, E, G, I). In contrast, the number of positively staining cells was notably high in the myocardium of Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants (Fig. 6D, F, H, J). Moreover, epicardial cells in controls stained strongly positive for VE-cadherin, while the mutant epicardial cells did not demonstrate any noticeable staining (Fig. 6I, J). Similar differences in the number of VE-cadherin, ZO1 and Claudin-5 positive cells were not detectable at E13. Thus, the increased number of smaller myocardial vessels can be explained by the abnormal remodeling and/or proliferation of subepicardial vasculature in embryos lacking Alk5-mediated Tgf-β signaling. Since epicardial Fgf-signaling has been implicated in the control of vascular proliferation during cardiac development and regeneration, we analyzed expression of several Fgfs in the ventricles using semi-quantitative PCR at E16.0. As can be seen in Fig. 6K, Fgfs1, -7 and -10 were expressed on equal levels in controls and mutants. Interestingly, Fgf9 was clearly upregulated in mutants when compared to controls (Fig. 6K, L).

Discussion

Alk5 and Tgf-β signaling in the myo- and endocardium

An important role of EMT during AVC development is well established (Markwald et al., 1981; Runyan and Markwald, 1983). Moreover, several key studies have demonstrated an instrumental role of Tgf-β superfamily signaling in induction of EMT in the chick (Potts et al., 1991; Potts and Runyan, 1989). However, the mechanism of EMT in mammals is still poorly understood. None of the Tgf-β mouse knockouts display any obvious defects that could be causally related to a failure in endocardial EMT(Kaartinen et al., 1995; Proetzel et al., 1995; Sanford et al., 1997; Shull et al., 1992). Moreover, a recent study reported that the Tgf-β type II receptor is not required in endothelial cells for normal EMT in vivo (Jiao et al., 2006). In fact, the recent data contend that Bmps rather than Tgf-βs would likely play more important roles (summarized in Fig. 7); first, it has been shown that Bmp2 is needed for induction of EMT in mice and second, Bmp type I receptors Alk2 and Alk3 are required in endothelial cells for successful EMT in vivo(Ma et al., 2005; Park et al., 2006; Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006; Song et al., 2007; Sugi et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005). On the other hand, we have shown before that in Alk2/Tie2-Cre mutants, phosphorylation of both Bmp and Tgf-β Smads is attenuated in the endocardium implicating a possible cross-talk between Tgf-β and Bmp signaling in endocardial transformation (blue hatched arrow in Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. A model illustrating Tgf-β superfamily signaling in endocardial EMT.

[selected findings of recent studies with relevance to Tgf-β superfamily signaling in endocardial EMT have been summarized]. Bmp2 (and possibly also other Bmps) secreted from the AVC myocardium binds to the Bmp and activin type II receptors, which in turn activate type I receptors Alk3 and Alk2 (Desgrosellier et al., 2005; Lai et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2005; Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006; Song et al., 2007; Sugi et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005). Similarly, other Tgf-β superfamily ligands secreted from the myocardium bind to type II receptors, which consecutively leads to activation of Alk5 that is required for endocardial EMT both in the chick (Mercado-Pimentel et al., 2007) and in the mouse (present study). While a recent study showed that Tgf-β type II receptor (TgfβRII) does not play any non-redundant roles in endocardial transformation in vivo (Jiao et al., 2006), the Tgf-β type III receptor was recently shown to play an important role in enhancing binding of Bmp2 to its receptors (Kirkbride et al., 2008). Whether this signaling (red hatched arrow) is dependent on Alk5 activity remains to be seen. Alk2- and Alk3 signaling mediated via Bmp Smads, particularly Smad1, leads to the increased expression of several target genes. Some of these events are likely pathway specific (Ma et al., 2005). Moreover, it has been suggested that activation of Tgf-β Smads in endocardial cells is dependent on Alk2 (blue hatched arrow), but not on Alk3 activity(Ma et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005). In a parallel canonical Tgf-β pathway, activated Alk5 signaling via Tgf-β Smads leads to activation of several known target genes (Mercado-Pimentel et al., 2007). Simultaneously, phosphorylation of Par6c with the type II receptor-Alk5 complex leads to a rapid degradation of RhoA, which is necessary for dissolution of tight junctions during EMT (Townsend et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2003).

In the present study we show that the Tgf-β type I receptor Alk5 is required for normal EMT in mice. This finding is consistent with a recent report from the Runyan laboratory, which demonstrated that Alk5 is required for AVC EMT in chick embryos (Mercado-Pimentel et al., 2007). However, our present results also raise an interesting question about the nature of Tgf-β signals mediated via Alk5, since as reported by Jiao and coworkers, Tgf-βRII is not involved with AVC EMT in vivo(Jiao et al., 2006). It is possible that ligands other than prototypic Tgf-βs are involved, or alternatively, maybe other Type-II receptors can substitute for the loss of Tgfbr2. Additional evidence implicating the unconventional partnership of Alk5 with other type II receptors comes from the myocardial defects found in Alk5/Tie2-Cre but not inTgfbr2/Tie2-Cre embryos (Jiao et al., 2006). This finding suggests that Alk5 signaling in the endocardium is important for the expression of mitogens essential for myocardial proliferation and survival of the trabeculated myocardium. Several knockout studies have shown that Bmps 6, -7, and -10 are necessary for the trabeculation (Chen et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2001). Therefore, it is possible the levels of these Bmps are reduced in the endocardium of the Alk5/Tie2-Cre embryos, or that defects seen in Alk5/Tie2-Cre mutants are due to inefficient Bmp response in endocardial cells. These Bmp signals are probably mediated by Alk3 but not by Alk2, since myocardial deletion of Alk3 (Gaussin et al., 2002), but not that of Alk2 (Wang et al., 2005) results in abnormal trabeculation. However, Tie2-Cre recombines not only in endocardial cells but also in other endothelial cells including the ones in coronary arteries. Therefore, we cannot exclude a possibility that some of the defects seen in Alk5/Tie-Cre mutants, e.g., the thin myocardium, maybe caused be a more generic failure in the vascular system.

Our finding that Alk5 mediated Tgf-β signaling may not be critical for development of the myocardium is concordant with findings of a recent study demonstrating that Tgf-β type II receptor in the myocardium is dispensable for cardiogenesis (Jiao et al., 2006). Collectively these studies argue that unlike Bmp receptor signaling(Gaussin et al., 2002), the corresponding Tgf-β signaling is not required cell autonomously in myocardial cells for cardiac growth and development.

Alk5 in epicardial cells

Several recent studies have emphasized a role of the epicardium in cardiac development, particularly in regulation of myocardial growth and function, as well as in generation of coronary arteries (Chen et al., 2002; Lavine and Ornitz, 2008). This is of significant interest, since understanding of mechanisms by which the epicardium regulates these processes during embryogenesis could result in strategies designed to effectively treat myocardial damage following the ischemic injury later in life. In this study, we show that Tgf-β signaling via Alk5 is critically important for appropriate function of the epicardium during cardiac development. In Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants, there is inappropriate attachment of the epicardium to the myocardial layer. Moreover, the expression of the cell adhesion molecules N-cadherin, and VE-cadherin is downregulated in mutant samples. Interestingly, a similar phenotype, i.e., the detached epicardium and thin myocardium, has been recently reported in neural crest-specific N-cadherin mutant mice. These mice also display decreased expression of N-cadherin in the epicardium (Luo et al., 2006). Therefore, it is conceivable that Tgf-β-mediated signaling via Alk5 regulates expression of genes of cell-adhesion molecules, e.g., cadherins, which in turn are needed for appropriate interactions between epicardial and myocardial cells to regulate myocardial proliferation. Alternatively, it is possible that inappropriate attachment of epicardial cells prevents the function of epicardium-specific mitogenic growth factors, which could lead to an attenuated myocardial proliferation seen in Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants.

It has been suggested that the epicardium functions as a signaling center for mid-gestational cardiac development (Lavine and Ornitz, 2008). One subgroup of these critical signals is Fgfs, which have been shown to play key roles in coronary vessel development in the mouse(Lavine and Ornitz, 2008). In the chick, both Fgfs and Bmps were reported to promote epicardial EMT, with Tgf-βs opposing the Fgf-induced epicardial EMT (Morabito et al., 2001). However, other studies have disputed these findings and suggest that in avians Tgf-βs will potently induce epicardial EMT(Compton et al., 2006; Dokic and Dettman, 2006). The importance of Tgf-β signaling in coronary vessel development was recently further emphasized by the findings of the Barnett group showing that coronary arteries fail to develop in mouse embryos lacking the functional gene encoding the Tgf-β type III receptor (Tgfbr3)(Compton et al., 2007). Our present in vivo study using the Alk5/Gata5-Cre mouse model demonstrates that while signaling via Alk5 in epicardial cells is needed for epicardial to mesenchymal transformation in epicardial cultures, it is not required for coronary artery formation. This is clearly highlighted by the fact that the mutant embryos survive until birth, indicating that coronary vasculature is sufficiently well developed to support adequate cardiac function. Instead, we observed that Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutants display a defective smooth muscle cell layer surrounding coronary arteries as demonstrated by immunostaining for vascular smooth muscle myosin. Tgf-β signaling can induce smooth muscle cell differentiation of multi-potent NCCs in vitro(Shah et al., 1996); however, the in vivo role of Tgf-βs in this process is controversial(Choudhary et al., 2006). Our present findings suggest that Tgf-β signaling through Alk5 is required for normal differentiation of epicardium-derived progenitor cells to a smooth muscle layer surrounding the coronary arteries.

The Alk5/Gata5-Cre mutant embryos also display a pronounced increase in the microvasculature in the myocardium when compared to controls. Recent studies have shown that in the adult zebrafish, which has a unique capacity for cardiac regeneration, the epicardium plays a critical role in generation of a fostering vascularized niche that can promote and support other aspects of regenerative cardiogenesis (Lepilina et al., 2006). Epicardially-derived Fgfs have been suggested to play a key role in development of myocardial vascularization, both during mouse cardiac development as well as during zebrafish cardiac regeneration(Lavine and Ornitz, 2008; Lepilina et al., 2006). Interestingly, our present studies suggest that Tgf-β signaling via Alk5 functions upstream of Fgfs during late cardiac development (E16-E18). In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that the epicardium-derived Fgf9 is a key mitogen in the myocardial proliferation (Lavine and Ornitz, 2008). However, it is likely that Alk5 signaling in regulation of Fgf9 expression is restricted to late gestation, since we could detect the congested myocardial capillaries only after E16.

To conclude, we demonstrate that signaling via Alk5 is required for normal EMT in the endocardium (see also Figure 7), and that Alk5 mediated signaling is required for normal epicardial-myocardial cell-cell interactions and for subsequent proliferation of the myocardium. Moreover, our present results imply that while Alk5-mediated signaling is not required for coronary vessel development per se, it plays a role in development of smooth muscle cell layer surrounding coronary arteries and controlling homeostasis of the myocardial vascular plexus.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Nagy for the technical assistance and S. Karlsson for the Alk5FX mouse line. This study was financially supported by NIH RO1 grants HL065484(to PR-L), and DE013085 and HL074862 (to VK).

References

- Anderson RH, Webb S, Brown NA, Lamers W, Moorman A. Development of the heart: (2) Septation of the atriums and ventricles. Heart. 2003;89:949–958. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.8.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartram U, Molin DG, Wisse LJ, Mohamad A, Sanford LP, Doetschman T, Speer CP, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Double-outlet right ventricle and overriding tricuspid valve reflect disturbances of looping, myocardialization, endocardial cushion differentiation, and apoptosis in TGF-beta(2)-knockout mice. Circulation. 2001;103:2745–2752. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.22.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernanke DH, Velkey JM. Development of the coronary blood supply: changing concepts and current ideas. Anat Rec. 2002;269:198–208. doi: 10.1002/ar.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CB, Boyer AS, Runyan RB, Barnett JV. Antibodies to the Type II TGFbeta receptor block cell activation and migration during atrioventricular cushion transformation in the heart. Dev Biol. 1996;174:248–257. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Shi S, Acosta L, Li W, Lu J, Bao S, Chen Z, Yang Z, Schneider MD, Chien KR, Conway SJ, Yoder MC, Haneline LS, Franco D, Shou W. BMP10 is essential for maintaining cardiac growth during murine cardiogenesis. Development. 2004;131:2219–2231. doi: 10.1242/dev.01094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TH, Chang TC, Kang JO, Choudhary B, Makita T, Tran CM, Burch JB, Eid H, Sucov HM. Epicardial induction of fetal cardiomyocyte proliferation via a retinoic acid-inducible trophic factor. Dev Biol. 2002;250:198–207. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary B, Ito Y, Makita T, Sasaki T, Chai Y, Sucov HM. Cardiovascular malformations with normal smooth muscle differentiation in neural crest-specific type II TGFbeta receptor (Tgfbr2) mutant mice. Dev Biol. 2006;289:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton LA, Potash DA, Brown CB, Barnett JV. Coronary vessel development is dependent on the type III transforming growth factor beta receptor. Circ Res. 2007;101:784–791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.152082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton LA, Potash DA, Mundell NA, Barnett JV. Transforming growth factor-beta induces loss of epithelial character and smooth muscle cell differentiation in epicardial cells. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:82–93. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desgrosellier JS, Mundell NA, McDonnell MA, Moses HL, Barnett JV. Activin receptor-like kinase 2 and Smad6 regulate epithelial-mesenchymal transformation during cardiac valve formation. Dev Biol. 2005;280:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokic D, Dettman RW. VCAM-1 inhibits TGFbeta stimulated epithelial-mesenchymal transformation by modulating Rho activity and stabilizing intercellular adhesion in epicardial mesothelial cells. Dev Biol. 2006;299:489–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudas M, Kim J, Li WY, Nagy A, Larsson J, Karlsson S, Chai Y, Kaartinen V. Epithelial and ectomesenchymal role of the type I TGF-beta receptor ALK5 during facial morphogenesis and palatal fusion. Dev Biol. 2006;296:298–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg LM, Markwald RR. Molecular regulation of atrioventricular valvuloseptal morphogenesis. Circ Res. 1995;77:1–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaussin V, Van de PT, Mishina Y, Hanks MC, Zwijsen A, Huylebroeck D, Behringer RR, Schneider MD. Endocardial cushion and myocardial defects after cardiac myocyte-specific conditional deletion of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor ALK3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2878–2883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042390499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hordijk PL, ten Klooster JP, van der Kammen RA, Michiels F, Oomen LC, Collard JG. Inhibition of invasion of epithelial cells by Tiam1-Rac signaling. Science. 1997;278:1464–1466. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson MR, Kirby ML. Neural crest and cardiovascular development: a 20-year perspective. Birth Defects Res CEmbryo Today. 2003;69:2–13. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao K, Langworthy M, Batts L, Brown CB, Moses HL, Baldwin HS. Tgfbeta signaling is required for atrioventricular cushion mesenchyme remodeling during in vivo cardiac development. Development. 2006;133:4585–4593. doi: 10.1242/dev.02597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaartinen V, Voncken JW, Shuler C, Warburton D, Bu D, Heisterkamp N, Groffen J. Abnormal lung development and cleft palate in mice lacking TGF-beta 3 indicates defects of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Nat Genet. 1995;11:415–421. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim RY, Robertson EJ, Solloway MJ. Bmp6 and Bmp7 are required for cushion formation and septation in the developing mouse heart. Dev Biol. 2001;235:449–466. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride KC, Townsend TA, Bruinsma MW, Barnett JV, Blobe GC. Bone morphogenetic proteins signal through the transforming growth factor-beta type III receptor. J Biol Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704883200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koni PA, Joshi SK, Temann UA, Olson D, Burkly L, Flavell RA. Conditional vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 deletion in mice: impaired lymphocyte migration to bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2001;193:741–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai YT, Beason KB, Brames GP, Desgrosellier JS, Cleggett MC, Shaw MV, Brown CB, Barnett JV. Activin receptor-like kinase 2 can mediate atrioventricular cushion transformation. Dev Biol. 2000;222:1–11. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson J, Goumans MJ, Sjostrand LJ, van Rooijen MA, Ward D, Leveen P, Xu X, ten Dijke P, Mummery CL, Karlsson S. Abnormal angiogenesis but intact hematopoietic potential in TGF-beta type I receptor-deficient mice. EMBO J. 2001;20:1663–1673. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine KJ, Ornitz DM. Fibroblast growth factors and Hedgehogs: at the heart of the epicardial signaling center. Trends Genet. 2008;24:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepilina A, Coon AN, Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Roberts RW, Burns CG, Poss KD. A dynamic epicardial injury response supports progenitor cell activity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Cell. 2006;127:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, High FA, Epstein JA, Radice GL. N-cadherin is required for neural crest remodeling of the cardiac outflow tract. Dev Biol. 2006;299:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Lu MF, Schwartz RJ, Martin JF. Bmp2 is essential for cardiac cushion epithelial-mesenchymal transition and myocardial patterning. Development. 2005;132:5601–5611. doi: 10.1242/dev.02156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwald RR, Krook JM, Kitten GT, Runyan RB. Endocardial cushion tissue development: structural analyses on the attachment of extracellular matrix to migrating mesenchymal cell surfaces. Scan Electron Microsc. 1981:261–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado-Pimentel ME, Hubbard AD, Runyan RB. Endoglin and Alk5 regulate epithelial-mesenchymal transformation during cardiac valve formation. Dev Biol. 2007;304:420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merki E, Zamora M, Raya A, Kawakami Y, Wang J, Zhang X, Burch J, Kubalak SW, Kaliman P, Belmonte JC, Chien KR, Ruiz-Lozano P. Epicardial retinoid X receptor alpha is required for myocardial growth and coronary artery formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA %20. 2005;102:18455–18460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504343102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito CJ, Dettman RW, Kattan J, Collier JM, Bristow J. Positive and negative regulation of epicardial-mesenchymal transformation during avian heart development. Dev Biol. 2001;234:204–215. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses KA, DeMayo F, Braun RM, Reecy JL, Schwartz RJ. Embryonic expression of an Nkx2-5/Cre gene using ROSA26 reporter mice. Genesis. 2001;31:176–180. doi: 10.1002/gene.10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivey HE, Mundell NA, Austin AF, Barnett JV. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates epithelial-mesenchymal transformation in the proepicardium. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:50–59. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Lavine K, Mishina Y, Deng CX, Ornitz DM, Choi K. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A signaling is dispensable for hematopoietic development but essential for vessel and atrioventricular endocardial cushion formation. Development. 2006;133:3473–3484. doi: 10.1242/dev.02499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts JD, Dagle JM, Walder JA, Weeks DL, Runyan RB. Epithelial-mesenchymal transformation of embryonic cardiac endothelial cells is inhibited by a modified antisense oligodeoxynucleotide to transforming growth factor beta 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1516–1520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts JD, Runyan RB. Epithelial-mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart can be mediated, in part, by transforming growth factor beta. Dev Biol. 1989;134:392–401. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proetzel G, Pawlowski SA, Wiles MV, Yin M, Boivin GP, Howles PN, Ding J, Ferguson MW, Doetschman T. Transforming growth factor-beta 3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat Genet. 1995;11:409–414. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfield A, Nieman MT, Knudsen KA. Cadherins promote skeletal muscle differentiation in three-dimensional cultures. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1323–31. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese DE, Mikawa T, Bader DM. Development of the coronary vessel system. Circ Res. 2002;91:761–768. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000038961.53759.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Feliciano J, Tabin CJ. Bmp2 instructs cardiac progenitors to form the heart-valve-inducing field. Dev Biol. 2006;295:580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan RB, Markwald RR. Invasion of mesenchyme into three-dimensional collagen gels: a regional and temporal analysis of interaction in embryonic heart tissue. Dev Biol. 1983;95:108–114. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford LP, Ormsby I, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Sariola H, Friedman R, Boivin GP, Cardell EL, Doetschman T. TGFbeta2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects that are non- overlapping with other TGFbeta knockout phenotypes. Development. 1997;124:2659–2670. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NM, Groves AK, Anderson DJ. Alternative neural crest cell fates are instructively promoted by TGFbeta superfamily members. Cell. 1996;85:331–343. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, Allen R, Sidman C, Proetzel G, Calvin D. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Fassler R, Mishina Y, Jiao K, Baldwin HS. Essential functions of Alk3 during AV cushion morphogenesis in mouse embryonic hearts. Dev Biol. 2007;301:276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugi Y, Yamamura H, Okagawa H, Markwald RR. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 can mediate myocardial regulation of atrioventricular cushion mesenchymal cell formation in mice. Dev Biol. 2004;269:505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend TA, Wrana JL, Davis GE, Barnett JV. Transforming growth factor-beta-stimulated endocardial cell transformation is dependent on Par6c regulation of RhoA. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13834–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710607200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada AM, Willet SG, Bader D. Coronary vessel development: a unique form of vasculogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2138–2145. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000098645.38676.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HR, Zhang Y, Ozdamar B, Ogunjimi AA, Alexandrova E, Thomsen GH, Wrana JL. Regulation of cell polarity and protrusion formation by targeting RhoA for degradation. Science. 2003;302:1775–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1090772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Sridurongrit S, Dudas M, Thomas P, Nagy A, Schneider MD, Epstein JA, Kaartinen V. Atrioventricular cushion transformation is mediated by ALK2 in the developing mouse heart. Dev Biol. 2005;286:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamora M, Manner J, Ruiz-Lozano P. Epicardium-derived progenitor cells require beta-catenin for coronary artery formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18109–18114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702415104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]